History of the Trombone in Brief

The histories of the trumpet and trombone diverged in the late fourteenth century. From then well into the seventeenth century, the trombone's principal role was in a "loud band" of shawms (later cornetts) and trombones. When that ensemble lost favor in most places, the trombone had nowhere else to go. It nearly disappeared, but found new roles in places where it persisted. When composers like Handel, Gluck, Mozart, Beethoven, and Musard started using it, it became ubiquitous again. (Who was Musard and how does he deserve mention in such august company? Read on.)

Slide trumpeter teases dog

Early history

Medieval trumpets did not look at all like modern trumpets. They consisted of a straight metal tube. The most impressive ones (and therefore the ones most prized by kings and other rulers who wanted to make a good impression) were very long. Even the shorter trumpets were made in sections. Players could take them apart to move them from place to place and reassemble them to play.

In the fourteenth century, someone rediscovered the ancient technique of bending a tube. Two bent sections and three straight sections make either an S-shaped trumpet or a loop. Within a few decades, someone figured out how to fit one tube inside another, so the whole instrument could be moved out along one shorter tube.

We would call the resulting instrument a slide trumpet. As early as1439, the Italians called it a "trombone." That word did not enter the English language until more than 300 years later. The modern trombone slide, meanwhile, developed some time before 1490.

The trombone, in whatever form, played only in the loud band with shawms (at first, two shawms and one trumpet, or later, trombone), but that ensemble could be heard nearly every place. It started in towns, where band served as night watchmen to warn of fires and other dangers. Even before the invention of the trombone these watchmen formed ensembles that entertained the townspeople, accompanied dancing, and so on. The trombone was much more suitable for the task than the trumpet.

In the fifteenth century, rulers started to hire similar bands for ceremonial purposes. The Dukes of Burgundy had a consistently good one. Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain and many other kings and dukes modeled their courts after Burgundy, but even minor nobles hired at least a two-piece band.

By the beginning of the sixteenth century, many of the major churches likewise had their own bands of shawms and trombones, which either alternated with the choir or played along with it. Over the course of the sixteenth century, typical bands grew from three to five parts or more. Except in France, the cornett eventually supplanted the shawm, so the typical five-piece band became three cornetts and two trombones.

Near death experience

Italian courts, especially in Florence, introduced a new kind of theatrical entertainment that experimented with mixing instruments of different groups. For the first time, trombones could be heard with soft instruments and solo voices--but only by people important enough to be on exclusive guest lists. It might have developed into a new role, but not everyone enjoyed the sound of mixed ensembles. By the time these costly entertainments developed into opera, a string orchestra supplanted the other instruments.

Meanwhile, the nobility had always maintained bands not so much for their own entertainment as to entertain common people, whom they despised. As towns became more prosperous, they tried to keep up with the tastes of the nobility. Inevitably, fashions changed. The shawm band had been less important in France than anywhere else. In the 1670s, the French court introduced a new band of oboes and bassoons. By the end of the century, almost every court in Europe had followed suit.

The papal court in Rome continued to maintain its traditional loud band

until the Napoleonic wars made it financially impossible to continue.

Future Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II had developed a love for Italian

ceremonial music, which still made extensive use of trombones. As

emperor, he introduced this music at his court in Vienna.

In England, where the royal court dominated national cultural life, the trombone soon disappeared from town bands as well. Apparently it had never been used much in French towns. In politically fragmented Italy and Germany, it remained in a few towns, notably Bologna, Naples, and Leipzig.

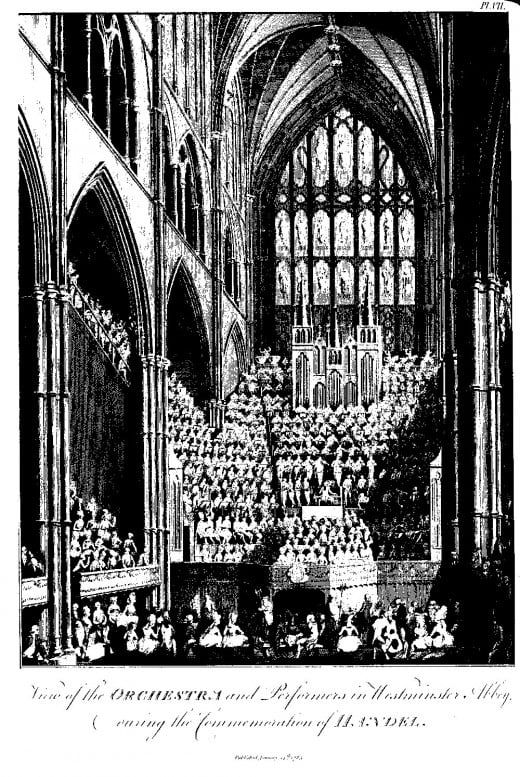

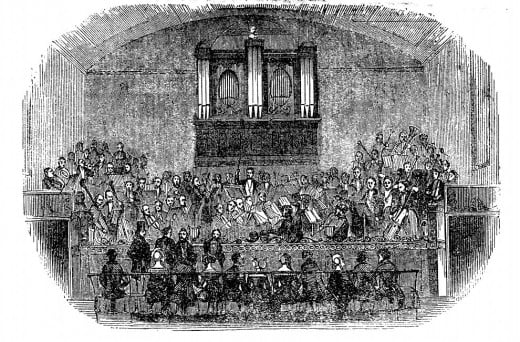

Handel Festival, 1784

Revival

The papal band did not attract much attention, but it apparently provided the trombonists when a few composers decided to introduce a trombone into oratorios, sinfonias, and concertos in the last half of the seventeenth century. In 1708 a young German student named Georg Friedrich Händel used one in La Resurrezione.

Later, in England after he had devised a new English form of the oratorio, he used three trombones in Saul and Israel in Egypt. He composed both in the same year, and apparently the trombonists were visitors from either Germany or Italy; he sketched out trombone parts for at least two later oratorios, but had to abandon the effort. The English nobility presented an impressive commemorative festival in 1784, and after that time, there were plenty of trombonists in England and lots of new music to keep them occupied.

Years later, Viennese composer Christoph Willibald Gluck visited Händel and must have studied Saul; in 1762 he introduced trombones into his opera Orfeo ed Euridice and modeled the biggest scene with trombones after the funeral scene in Saul that includes the famous "Dead March." After he revived the opera in 1774 for production in Paris, hardly any French composer failed to include trombones in operas.

Meanwhile, composers in the Viennese court maintained an unbroken tradition of using trombones in church music and oratorios. By the generation of Johann Joachim Fux and Antonio Caldara, many of them wrote frequent and florid trombone solos. The trombone solo in Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's Requiem is therefore not an innovation, but the last example of an old tradition.

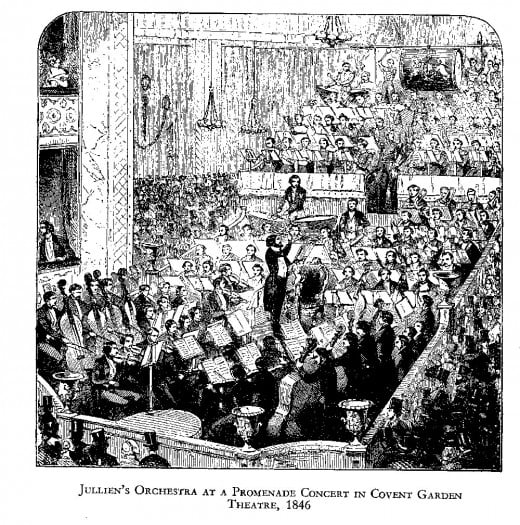

An orchestra in the Hanover Square Rooms, London, 1843

"Classical" music

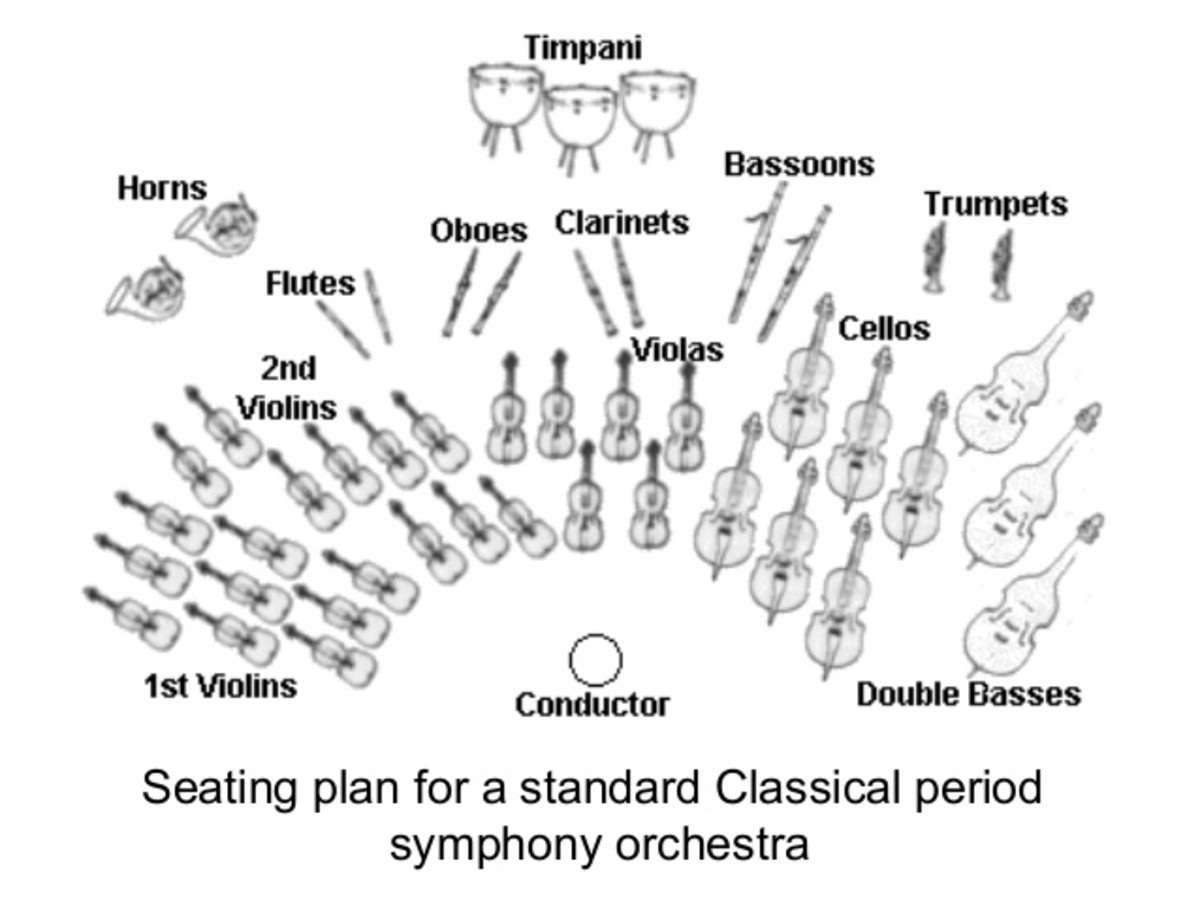

It appears that a lot of people in the early nineteenth century did not welcome the trombone into the orchestra, but several pieces everyone wanted to hear required them: Mozart's Requiem and arrangement of Händel's Messiah, Creation and Seasons by Haydn, Beethoven's Fifth, Sixth, and Ninth Symphonies, and others. The standard of trombone playing seems not to have been very good at the time, but it grew

As orchestral trombone sections grew in proficiency, composers started demanding more of them. Hector Berlioz and Richard Wagner stand out as composers who made unprecedented technical demands not only on the trombones, but every instrument in the orchestra. By mid-century, nearly every composer of orchestral music routinely used three trombones and could count on proficient players.

The earliest purely orchestral music with trombones uses them only for harmonic filler. The parts are boring to play and add little but weight and volume to the effect of the piece. As trombone sections grew in competence, composers provided them with more important and interesting parts. Johannes Brahms's symphonies each have chorale passages for trombones. By the end of the nineteenth century, some pieces even had solos for trombone, the longest and best known being in Gustav Mahler's Third Symphony.

The twentieth century brought no new developments to either the technique or prominence of trombones in orchestral works. Many works in the repertoire contain thematically important, exposed parts for the trombones, in harmony or unison, as well as a significant number of solos. Most trombone solos are short, but works with long, prominent ones include Jan Sibelius's Seventh Symphony and Maurice Ravel's Bolero.

Outside the orchestra, trombones hardly ever participated in classical music. Some fairly obscure French and Russian composers of the nineteenth century provided a few works of true brass chamber music. Francis Poulenc composed his Sonata for brass trio (trumpet, horn, and trombone) in 1922.

The Paris Conservatory commissioned solos for trombone and piano for its annual contests; Camille Saint-Saëns wrote one, but these were contest pieces, not concert pieces. After Paul Hindemith's Sonata for Trombone and Piano (1940), other composers (usually less well known than Hindemith) began to provide many concert pieces for trombone and piano, or even unaccompanied trombone. Many colleges and universities, at least in the United States, began to require a formal recital as a graduation requirement.

There have been a few concertos from trombone and orchestra dating back to the eighteenth century, but none have attracted wide attention or entered the repertoire of major orchestras. Christopher Rouse's Trombone Concerto won the Pulitzer Prize in 1993. It remains to be seen if more orchestras will program works with solo trombone as a result.

Promenade (pops) concert

"Vernacular" music

I use the term "vernacular" rather than "popular" because it is both broader and more accurate. In the early nineteenth-century as now, not everyone appreciated "classical" music. Much of what seems "classical" music now was not accepted as such then (Rossini's operas, for example), some of which contain exciting trombone parts of unprecedented difficulty.

Audiences of the time who did not appreciate the classics preferred novelty, which traveling virtuosos provided in abundance. They specialized in dazzling variations on familiar tunes. Most were pianists and violinsts, but a surprising number were trombonists. Self-taught Frenchman Felix Vobaron claimed to be the first trombonist to play variations in public.

The same audiences also loved dance music. Dance orchestras such as those led by Josef Lanner and Johann Strauss I in Vienna, Jullien in London, and Philippe Musard in Paris provided it in abundance. Musard invented the promenade concert, which allowed his orchestra to keep working in the off season. All of these orchestras eventually included trombones. Musard was the first composer to use a trombone to play the melody. He also featured trombone soloists Antoine Dieppo and Edouard Dantonnet.

Other well-known soloists include the Germans Friedrich Auguste Belcke and Carl Traugott Queisser, the Italian Giovacchino Bimboni (who played for a while with Johann Strauss II), and Felippe Cioffi (who first made a sensation in New York and New Orleans and then moved to London).

Wind bands (mostly military bands in Europe and civilian bands in the United States) likewise included trombones and presented popular concerts. In the United States, the earliest professional touring band, led by Patrick S. Gilmore, featured Frederick Neil Innes as trombone soloist. After Gilmore's death, John Phillip Sousa led the most prominent band, with Arthur Pryor as his first trombone virtuoso. Both Innes and Pryor eventually founded their own bands.

Changing public tastes caused a decline in these large bands, and the Great Depression of the 1930s finally caused most of the remaining ones to fold. Smaller dance bands, whose music was influenced by jazz, became more popular.

Jazz began around 1900 in New Orleans, where trombonists like Kid Ory developed the so-called tailgate style. New Orleans bands were fairly small. When the dance bands started playing jazz, the instrumentation of five saxophones, three or four trumpets, three or four trombones and rhythm eventually became commonplace. (Even though this ensemble is much smaller than the older wind bands it supplanted, it is larger than either earlier or later jazz groups, and is therefore known as the big band.)

Personnel in these bands changed frequently. The trombone section of "Tricky Sam" Nanton, Juan Tizol, and Lawrence Brown in Duke Ellington's band stayed together longer than most sections. Trombonists Glen Miller and Tommy Dorsey both founded very successful bands.

A style called bebop developed in the late 1940s. Rather than some kind of a band, bebop ensembles most often consist of one soloist and a rhythm section. The soloist can play any instrument used in jazz, but because bebop artists played at breakneck speed, is seemed that the slide trombone would no longer have a place in the new jazz until J. J. Johnson demonstrated his mastery of the techniques. After Johnson, more trombone soloists rose to prominence than can be listed in a short overview article.