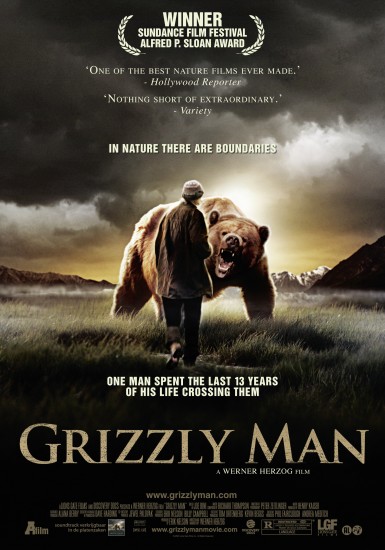

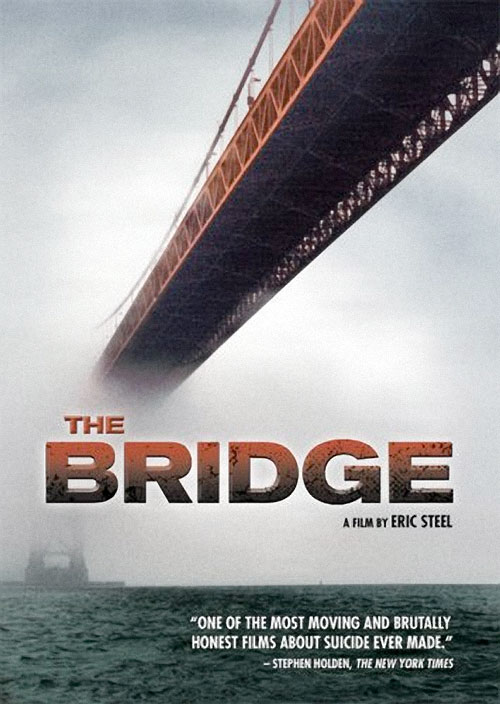

How to Document A Violent Death: An In Depth Review of Grizzly Man and The Bridge

Similar, but not the Same

Grizzly Man (Herzog, 2005) and The Bridge (Steel, 2006) tackle the topic of a violent death so poetically the viewer can almost forget they are watching movies about death. In many ways, the movies are similar. They tackle a grim topic and try to ease the viewer into their world so it doesn’t become overwhelming.

In Grizzly, the story revolves around Timothy Treadwell a wilderness man hell bent on saving the bears.

In The Bridge, the story revolves around several people of different ages and backgrounds, but united by committing suicide from the Golden Gate Bridge.

It is important to look closely at the differences between the directors approach on filming their subject’s violent deaths. What do they show? What do they omit? How is it presented? Even a couple of differences can change the way a film is perceived and how much it can be trusted.

My Review of The Bridge

- Film Review: The Bridge

This is a review for the 2006 documentary The Bridge about those who commit suidice by jumping from The Golden Gate Bridge. Read the review and learn some interesting facts about The Golden Gate Bridge and the film, then watch the trailer.

My Review of Grizzly Man

- Film Review: Grizzly Man

This is a review for the 2005 documentary Grizzly Man, directed by Werner Herzog. Read the review and learn some fun facts about Timothy Treadwell and the film, then watch the trailer. It is an intriguing film that examines one mans fight to save the

Uses of the Environment

The environment, and the way each director builds their stories around it, affects the poetic way the deceased are shown and the way the viewer sees them. The vast landscape of icebergs and thick wilderness is just one of the highlights in Grizzly Man. Set in the Alaskan

Federal Reserve, it is easy to get swept away in the footage of clear streams and untouched brush taken by both Timothy Treadwell and Herzog.

It is that simple beauty that Herzog admits he was drawn to while watching Treadwell’s footage. The beautiful, serene environment is a harsh juxtaposition next to the violent death of Treadwell and his girlfriend, Amie Huguenard.

Herzog uses the environment to great effect, showing the wild brush, softly twisting in the wind in one scene and in the next showing Treadwell standing in the same frame discussing how he could die, but would not. The beauty of the shot with the knowledge that Treadwell was wrong (he would indeed die by the ‘paws and the claws of the bears’)the viewers sense of who Treadwell was, how his environment affected him and how it affects us. How can something so horrible happen in such a beautiful place?

Steel uses the same poetic effect of the environment in The Bridge. Though set in one of America’s largest metropolitan cities, San Francisco, Steel goes through great effort to remove the viewer from the city itself.

The Golden Gate Bridge becomes a mountain over a blue ocean and near green patches of grass with yellow flowers. Instead of highlighting the many skyscrapers that litter the skyline, Steel focuses on the ocean, the mountains, the grass, the flowers and the fog. In effect, he is creating a more serene environment to juxtapose the horrors of the suicides.

The scene that seems to express this best is the shot of the Golden Gate Bridge with mountains behind, the ocean rippling with soft waves and the fog, a group of scattered pillows floating about. It is beautiful. Even the splash of water that comes from nowhere is beautiful…until the viewer realizes that the splash is someone’s death.

The Poetic Mode

The use of the poetic mode is important for the way the deceased is viewed. In effect, the calm, serene environment in both films removes the viewer from any chaos that death might create within their own perceptions. Instead, the viewer is forced to deal with the deceased themselves.

In Grizzly Man, we are forced to deal with Timothy Treadwell’s choices, including asking, “Was he wrong?” or “Why did he stay?” There are many more questions the viewer can ask, of course, but the focus is solely on Treadwell, not the environment or the bears.

In The Bridge, the viewer could be concerned with the why (some answers are given for some) or the how (footage is shown how many choose to jump off the bridge), but the focus of the film returns to the ‘who’ (the jumpers, 24 deceased in 2006).

Who were the jumpers? Because there were so many of them, Steel chose to jump between several different stories (Gene Sprague, becomes his bookend) intermixed with interviews and the environmental shots. Though there seems to be a lot going on, the focus is always brought back to the deceased (Gene, Lisa, Philip, David, Ruby, Jim).

The viewer gets a good perspective of who these people were from the interviewees, who were their friends, family and caretakers. The viewer also gets to see those silent moments of the deceased before that last jump off the bridge. The viewer sees this from an unencumbered and purely observational perspective that Steel provides. One might consider the bridge, but the focus is on the people that have died.

To Love is only Human

Herzog and Steel have a similar outcome in the descriptive ways the deceased are ‘moved’ as well as humanized. A common trend that seems to connect Treadwell to those highlighted in The Bridge, is the great motivator of ‘love’. Treadwell discusses his romantic (in)stability, ex-girlfriends are interviewed, lady friends that must be stated as platonic are interviewed and the girlfriend he died with are discussed but, as Herzog puts it, “is shrouded in mystery.” For Treadwell love seems to be the thing that ‘moved’ him; his love for the animals as well as his need to be loved.

The scene that exemplifies this is when he sits in his tent and pleads to God, Allah and the ‘flying thingie’ to let it rain because “Downey is eating her babies!” His pure, uncensored love for the bears is expressed and though it might be off-putting, it shows who Timothy Treadwell really was. The same can be said of the scene where he stands in amazement, touching Wendy the bear’s poop. If you haven't seen the film yet, yes, he does touch the poop (see the picture to the right).

In fact, he's honored to do so.Treadwell loved those bears and it seems he felt that loved returned. Whether or not the viewer agrees with such a sentiment, it is clear that moment was honest and expressive of Treadwell’s love.

The Bridge confronts love a little differently, though it is as expressive of the jumper’s mentalities as Treadwell’s touching of the poop. Love as a loss is discussed in Gene’s, Lisa’s, David’s and Ruby’s stories. As Treadwell’s love got him to stay in danger’s way, love seemed to be one of the many triggers that sent the jumpers to The Golden Gate Bridge. The difference isn’t really that much. It can be said that Treadwell’s insistence on staying later in the season (than he was used to) was ‘suicide by bear’.

Love is one of those things that humanizes, that links us all together. By bringing up love, the viewer not only gets an emotional link to the dead, but also an idea about what drove the deceased to do what they did (stay too late in the season, jump off a bridge).

The Animal in all of Us

Herzog and Steel also find unusual ways to describe their deceased in their films. To detail who his deceased was Herzog uses Treadwell’s own behavior to give the viewer a good perspective. By using an interview with Larry van Daele, a bear biologist who never met Treadwell, Timothy is described as acting like a bear, huffing and woofing. This isn’t unusual for a guy who loved bears so much he touched their poop.

However, to find such parallels in animalistic descriptions in The Bridge is something to be noted. The references are not consistent in their descriptive nature, but animals are used often enough. Gene is described as ‘crying wolf’. Sebastian (the tourist’s oldest son) describes Lisa as ‘acting like a gorilla’. Philip’s parents are interviewed being affectionate towards a small dog as they discuss their love for their son. Kevin Hines talks about a shark eating him and being saved by a seal.

The link between animal and people has been discussed, but the association in these instances gives a thought provoking visual of the dead. A bear, a wolf, a gorilla gives the viewer the idea that the dead were closer to animals than they were to people.

In many ways it separates the viewer from the dead and allows us to see them in a different dimension than we see ourselves. As much as they are like us, these dead are not like us. As a viewer we are then moved to ask how and why. This allows us to focus back on the deceased, picking apart what makes them and what caused them to act in a way that eventually causes their deaths.

Reflexivity

Herzog and Steel have many similarities in their approach to a violent death in their films, with one large difference that alters the way the deceased is viewed: reflexivity.

- To be reflexive is to structure a product in such a way that he audience assumes that the producer, the process of making, and the product are a coherent whole…that being reflexive means that the producer deliberately and intentionally reveals to his audience the underlying epistemological assumptions that caused him to formulate a set of questions in a particular way, to seek answers to those questions in a particular way, and finally to present his findings in a particular way.[i]

Jay Ruby makes it clear that he believes that all filmmakers have an obligation to be reflexive in their work.

I argue that the reflexivity Herzog used in The Grizzly Man removed the emphasis from Treadwell and put the spotlight on Herzog instead. Two scenes highlight Herzog’s counterproductive acts.

The first scene is when Treadwell speaks directly to the camera about his issues with the Park Service. Timothy goes into a curse laden rant about the injustices towards the animals. Instead of allowing the viewer to listen to Treadwell’s personal opinions, Herzog censors him saying, “Now Treadwell crosses a line with the Park Service, which we will not cross. He attacks the individuals with whom he worked with for 13 years.”

Herzog may not have agreed with what Treadwell was saying, but what Treadwell was saying was his own uncensored feelings. Was what he was saying vulgar? Probably so. Was what he was saying true? Probably not. But what he was saying was what he truly believed and those words (whether Herzog or the viewer believes them or not) defined who Timothy Treadwell was and what he was fighting for. As the narrator and ‘the voice of God’, Herzog basically shows the viewer the man behind the curtain, then tells us to forget we see the man behind the curtain. This isn’t possible any more. Herzog could have refrained in showing the scene at all, but chose to insert his own opinions and by doing so he removes the emphasis from Treadwell and egotistically places it on himself.

Herzog does the same in the famous scene where he places himself in front of the camera and listens to the audiotape of Treadwell and Huguenard dying. With Treadwell’s ex-girlfriend, Jewel Palovak, sitting in a chair holding Treadwell’s camera, Herzog listens to the tape then tells Palovak, “You must never listen to this.” He, in essence, is telling the viewer that he will not allow them to listen to the tape (which he doesn’t) then proceeds to tell her to immediately destroy the tape (so that the viewer can never hear it).

The link to Treadwell becomes something Herzog gives to us and is on the director’s terms. This brings many questions in the viewers mind, including what is Herzog not allowing us to hear or see? The picture of Treadwell that Herzog had been putting out there for us now appears more like a personal drawing Herzog scribbled on a napkin than it does a portrait of an individual whose depths, textures and complexities were of his own making. It is no longer about Timothy Treadwell, but about what Werner Herzog thinks of Timothy Treadwell.

Herzog listening to the audio of Treadwell's death in Grizzly Man

Kevin Hines

The Bridge takes a different route, staying out of self-reflexivity and not speaking for the dead. This can be shown by one of the jumpers who didn’t succeed in committing suicide. Kevin Hines is shown distraught, on the verge of tears, fidgety and at times lacking coherence.

A handsome young man, he does not give the appearance of a stable individual. At the end of the film, Hines states he would not try to kill himself again, though as a viewer, I’m not sure I believe him. Not a pretty picture, but an honest one.

Watch the video below to see the interview with Kevin Hines from The Bridge. Note the picturesque setting Steel uses in the shots leading up to the interview. They are as beautiful as shots taken in Alaska for Grizzly Man.

I Got It. Did You?

And contrary to what Herzog might believe, I didn’t need Steel to censor it for me. I got it. The same can be said of Treadwell’s death on audiotape. I watched 24 people jump to their deaths in The Bridge and I think I handled it just fine. Was it unsettling? Yes. Is it haunting? Yes.

What Herzog seems to have forgotten is, the film he created incites discussion about a topic that is so often left silent: a violent death. He seems more interested in his own discussion with the people in his movie than inciting a discussion with his viewers about his movie and, in the end, about Timothy Treadwell’s death.

Eric Steel, on the other hand, takes a back seat. There is no man behind the curtain. In fact, there is no curtain at all. There is just the bridge and the stories of those who jumped off it told from those who loved them, strangers who saw them and the camera that caught them in action. There are as many questions left at the end of Grizzly Man as there are in The Bridge, but the latter the questions revolve around the people that died and the former revolve around Werner Herzog and his choices.