Nirvana Fans and Fandom in the Noughties

An Explanation

This essay was originally written in 2003 for my degree course. Some of the arguments might seem a bit old hat now so I'm getting my excuses in early!

Some people might just object to the lazy dualism at the heart of the argument, but it serves to provide contrast. If you're particularly keen to express your point of view on the subject please feel free to add a comment! Try to keep it clean though.

The original title was "Compare two different representations made by fans of Nirvana and Kurt Cobain for their own community. What do they say about the fans in relation to mainstream stereotypes of fandom?" But that would suck as a hub title.

As with most of my academic essays this one is fully Harvard referenced, and you can use it as a source in your own work should you have any use for it!

Headers and pictures added in 2011 for the benefit of readers!

Introduction - Establishing what 'fans' are.

This essay aims to establish what the mainstream stereotypes of fandom are, and then discuss the ways in which two different representations of Nirvana fans relate to these stereotypes.

First, fandom itself must be established. Matt Hills, in Fan Cultures , describes fandom as “both a product of ‘subjective’ processes (such as the fans’ attribution of personal significance to a text), and is also simultaneously a product of ‘objective’ processes (such as the text’s exchange value, or wider cultural value)” (2002: 113). Daniel Cavicchi (1998) suggests that fans are “ideal consumers”

Abercrombie & Longhurst (1998: 121) treat fans and enthusiasts as “a form of skilled audience”, and claim that by participating in fandom “people are helped to construct particular identities.” This suggests that fandom can empower fans, making them more ‘skilled’ than ordinary viewers and providing a means of reinforcing their identity.

This was the beginning of a complex cultural phenomenon...

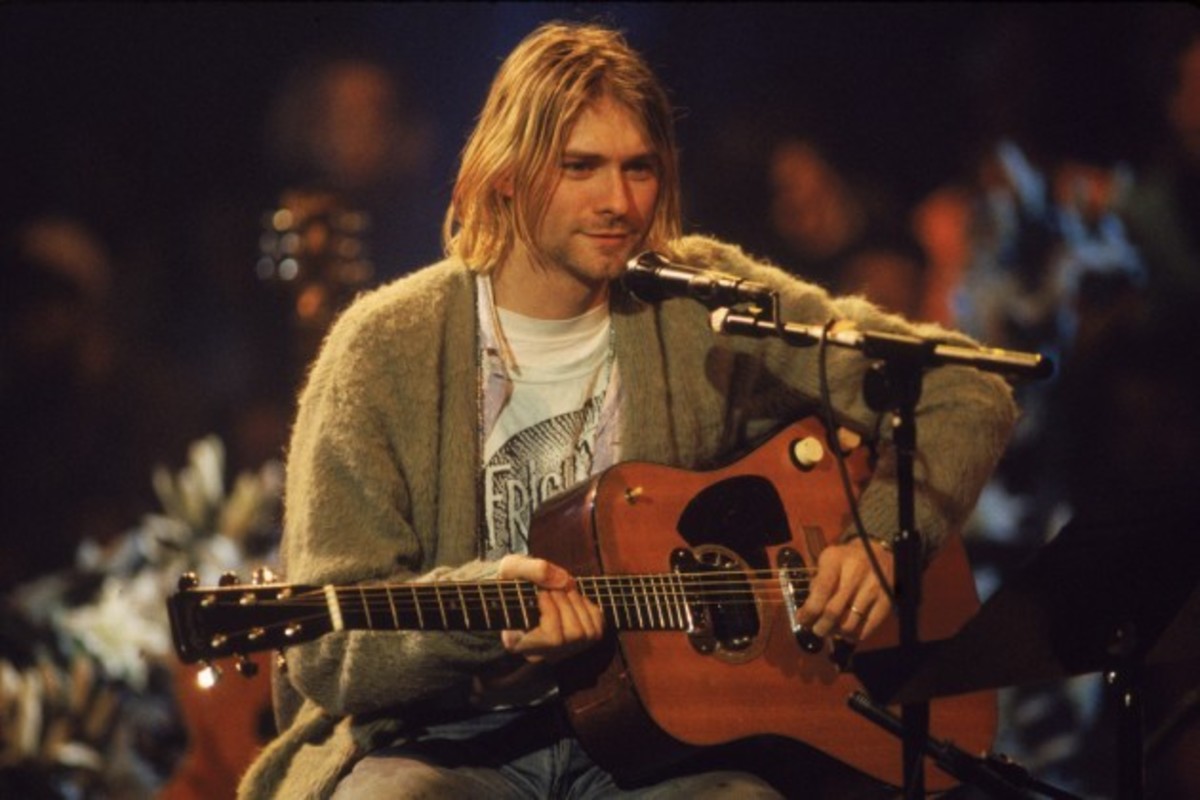

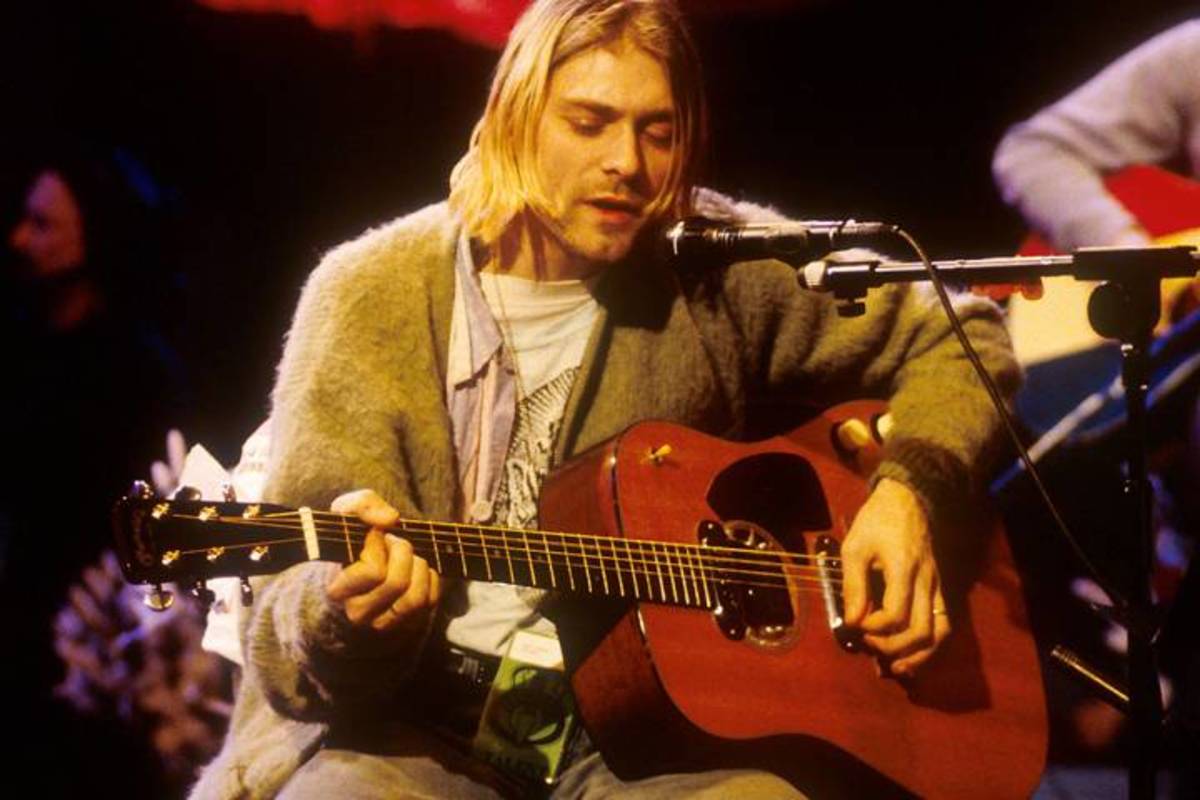

Since the suicide of Kurt Cobain in April 1994, Nirvana fandom has taken a different meaning. The death of Cobain at the height of his fame sent shockwaves through the alternative music scene, and led to ‘copycat’ suicides and panic. Dave Thompson describes the day his death was announced:

“At one point, crisis hotlines in Seattle were taking up to quarter of an hour to answer their phones, and as late as midnight, there was still a lengthy delay. One volunteer worker admitted she had never experienced a day like it - and hoped she never would again.” (Thompson, 1994: 163)

This was the beginning of a more complex cultural phenomenon.

There are numerous problems surrounding fan research and these problems must be acknowledged. Matt Hills (2002: 21) talks of a “moral dualism” within academic accounts of fandom, which sets up an opposition, even a sense of mistrust, between fans and academic researchers. There is a tendency to see fan behaviour as either ‘good’ or ‘bad’ from an academic viewpoint, and through media stereotyping fans expect to be seen in a negative light. Also, Hills describes the problem of being a scholar-fan or fan-scholar. A fan would argue that you cannot understand fandom from the outside, while a scholar would argue that objective critical analysis of fandom becomes impossible once you are a fan.

To research Nirvana fans in this context, research was undertaken to identify two representations of fans. This involved finding a Nirvana fan culture and studying some recurring themes within that culture. The Internet Nirvana Fan Club (www.nirvanaclub.com) features a large amount of information on Nirvana, and hosts discussion boards, a chat room and a tributes section containing poetry and letters from fans about Nirvana and Kurt Cobain. The discussion boards and the tributes section provided the bulk of the material used to define two recurring representations of fans. In addition to this, data gained from observing and conversing with Nirvana fans between 1995 and 2003 was used to create a clearer distinction between the two types.

Two Types of fan

The two representations of fans defined by research are still generalisations to some extent, but the boundaries are narrow enough to allow for analysis. For simplicity they are labelled Type One and Type Two.

Type One:

Type One fans are the most prominent and vocal Nirvana fans on the INFC message boards and tribute pages. Type One fans share a number of characteristics. They will claim to love or be devoted to Kurt, whether male or female. They hail him as a genius, a great musician and the inventor of the ‘grunge’ genre. They discuss and debate in great detail the events of April 1994, and some rally around theories claiming that Courtney Love, Cobain’s wife, either killed him or had him killed. Those who believe it was suicide ask “why he was taken from us?” and blame the press for hounding him. Some fans seemingly cannot accept that he is gone, either stating their disbelief or claiming that he is there for them to turn to, suggesting both religious connotations and Cobain as a role model. They tend to have a detailed knowledge of events in the history of Nirvana and the life of Kurt Cobain, and will either own or be aware of rare Nirvana songs, often citing an obscure track as their favourite song. Some Type One fans are described as “obsessive”, despite some admitting that they were too young to remember Nirvana when Cobain was alive.

Type Two:

This type of fan is less prominent than type one, and tend to look down on some of the behaviour of Type One fans, such as the “Cobain-obsessors”. Type Two fans tend to be a few years older (where age is given), and as such were either fans of Nirvana during their active career or became fans in the years immediately following his death. They identify with Kurt as a troubled individual, but also as an ordinary person, and are offended by the way Kurt is almost worshipped by Type One fans, as Type Two fan Scott Stetson explains:

“The obsession of some Nirvana fans is so strong, that is has turned Kurt Cobain into the opposite of what he stood for. Kurt had said many times before his untimely death that he didn’t want to be a rock star, just play music. And part of what made Nirvana so great is that they were just three ordinary guys…they could be anybody…they could be you. Their songs are not difficult to play, so anyone could join in if they wanted.” (www.iconofan.com/readerrants/2001/sep/nir.shtml)

This shows that, for these fans, Nirvana’s simplicity and normality, the impression that Nirvana were ‘down to earth’ and approachable rather than egotistical rock stars, was a key part of their appeal. They see those that ‘hero-worship’ Kurt as missing the point. Type Two fans generally accept the suicide theory, but even those that believe Cobain was murdered tend not to discuss the subject too much anymore, seeing the debate as somewhat pointless since nothing will bring him back. Type Two fans will have a few rare Nirvana songs, but are more interested in the official releases. They may once have been a Type One fan, but are now ‘over’ Cobain’s death.

Stereotypes of fans

Mainstream stereotypes of fandom tend to be negative. From a theoretical and psychoanalytical viewpoint, Henry Jenkins, author of Textual Poachers , saw fandom represented as “intellectually debased, psychologically suspect, or emotionally immature.” (Jenkins, H., 1992: 17) He went on to describe the way the stereotypical fan in constructed by ideology:

“The stereotypical conception of the fan… amounts to a projection of anxieties about the violation of dominant cultural hierarchies. The fans transgression of bourgeois taste and disruption of dominant cultural hierarchies insures that their preferences are seen as abnormal and threatening by those who have a vested interest in the maintenance of these standards.” (ibid.)

However, Jenkins also presents a list of fan stereotypes based on their representation in the mainstream media (ibid. 10). His list described popular stereotypes about Star Trek fans, but in the following quotation it has been paraphrased to apply to all media products:

“a. are brainless consumers who will buy anything associated with [the text/media product];

b. devote their lives to the cultivation of worthless knowledge;

c. place inappropriate importance on devalued cultural material;

d. are social misfits who have become so obsessed with [the text/media product] that it forecloses other types of social experience;

e. are feminized and/or desexualized through their intimate engagement with mass culture;

f. are infantile, emotionally and intellectually immature;

g. are unable to separate fantasy from reality.” (ibid. 10)

On comparison with this list of stereotypes, Type One fans can be seen as the ‘stereotypical’ Nirvana fan:

- While ‘brainless consumers’ would be a harsh label for any group, Type One fans are associated with purchasing albums by former Nirvana members, however obscure, as well as Nirvana bootleg recordings. Another example is the trade in unused tickets from Nirvana’s 1994 European tour, which sell for around £50.

- Type One fans gather as much information as they can on Nirvana, especially Cobain’s last days. While useful within their fan community, it is largely useless outside of it.

- Unfinished songs, b-sides and studio out-takes could certainly be described as ‘devalued cultural material’, and it is precisely these things that Type One fans seek out.

- It is difficult to determine whether Type One or Two fans are ‘social misfits’, and would require more empirical research to establish.

- This is also difficult to determine, and would require more research.

- The reliance on Cobain as an idol, role model, hero or ‘god’ to some Type One fans would point to a level of emotional and intellectual immaturity.

- It is certainly a ‘fantasy’ that Cobain or Nirvana invented grunge. As Gina Arnold proves in On the Road to Nirvana (1993) the grunge genre was developed by bands such as Mudhoney and Soundgarden, who had formed several years earlier than Nirvana. Then there are the fans who continue to debate the death of Kurt Cobain, some still holding the view that Courtney Love personally killed him, despite the fact she was several hundred miles away at the time.

While imperfect, this comparison shows that Type One fans have much in common with media stereotypes of fans. Does this mean that Type Two fans are not ‘real fans’? This question would probably rile the Type Two fans, as it is the stereotypes they do not conform to that irritate them. While Type One fans claim to ‘love’ Kurt, Type Two fans ‘respect’ or ‘admire’ him, not on the level a non-fan respect an artist, but in a way that expresses their appreciation without ‘transgression’ of ‘dominant cultural hierarchies’, without appearing immature and without becoming a ‘brainless consumer’ of Cobain-related merchandise. They don’t elevate him to a higher plane, because their appreciation for him is linked to his normality, his ordinary qualities that allow them to relate to him, rather than a make-up caked movie star or a manufactured, expensively dressed pop star.

Where the two fans agree is the music, perhaps because this is the core of the text. Jenkins describes a type of fan behaviour which shows this link:

“Fans speak of ‘artists’ where others can only see commercial hacks, of transcendent meanings where others find only banalities, of ‘quality and innovation’ where others see only formula and convention.” (1992: 17)

Does this count as a conclusion?

It is what the fans see, where ‘ordinary’ audience members do not, that draws the distinction between fan and non fan. Nirvana sold over nine million copies of ‘Nevermind’, which must strike the average consumer as the work of a commercial band. Cobain’s lyrics, held close to the heart of many fans, have been ridiculed as meaningless or inaudible (see The Archive of Misheard Lyrics for some examples) by casual listeners.

Poll

Are you a passive or active consumer?

Bibliography

- Abercrombie, N. & Longhurst, B. (1998) Audiences, Sage: London.

- Arnold, G. (1993) On the Road to Nirvana, St. Martin’s Press: New York.

- Cavicchi, D. (1998) Tramps Like Us: Music and Meaning Among Bruce Springsteen Fans, Oxford University Press: New York.

- Hills, M. (2002) Fan Cultures, Routledge: London.

- Jenkins, H. (1992) Textual Poachers: Television Fans & Participatory Culture, Routledge: London.

- Thompson, D. (1994) Never Fade Away: The Kurt Cobain Story, St. Martin’s Press: New York.

Sources from the internets (probably long gone)

- Stetson, S., Nirvana Fans…Get A Life, available fromwww.iconofan.com/readerrants/2001/sep/nir.shtml [accessed 20/11/2003]

- The Internet Nirvana Fan Club, available fromwww.nirvanaclub.com [accessed 22/11/03]

- The Archive of Misheard Lyrics,www.kissthisguy.com [accessed 29/11/03]