Part-writing Chords: Minor Keys II

This Hub is the second part of an extended discussion of part-writing in minor keys. If you’ve come upon this article without reading Part One, you may wish to go back and read it first; it is linked in the sidebar to the right and below.

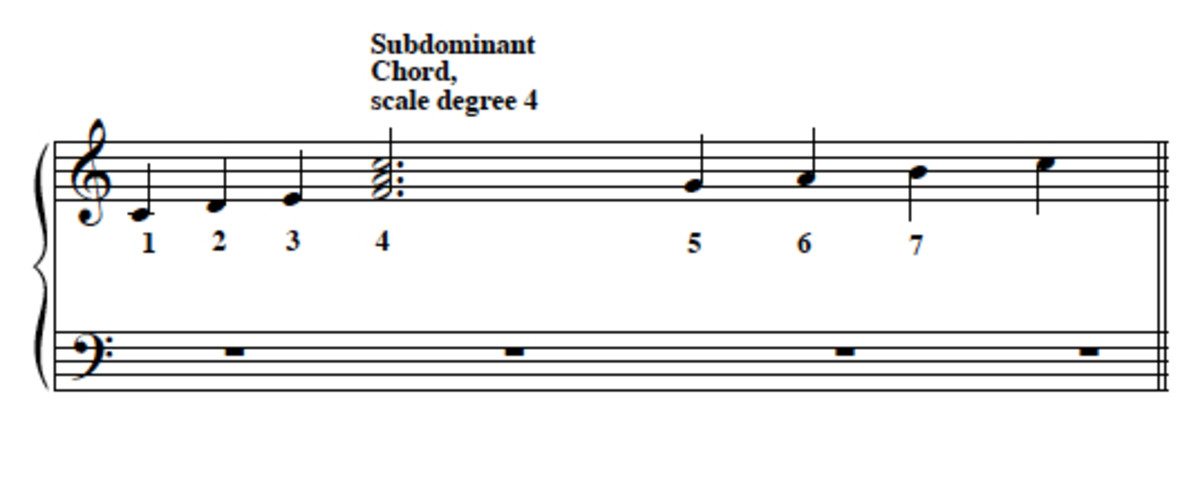

Part One examined part-writing minor-key tonic (i), dominant (normally V), subdominant (iv or IV), and supertonic (iio or ii) triads, and identified two major ‘traps.’

- Part-writing In Minor Keys I

Part-writing in Minor Keys I, the sixth in a series, looks at issues and common voice-leading patterns in writing root-position tonic, dominant, subdominant, and supertonic triads in minor keys. Includes practice exercises!

The first trap is that when writing minor-key dominants one must remember to raise the leading tone. It's very easy to forget this, but without that raised seventh scale degree, a chord built on the dominant just doesn't sound like a dominant chord!

(Functioning dominant triads in minor keys require a raised leading tone, following the harmonic minor form of the scale. This is also a handy way to recognize minor-key music on the page—if there are frequent sharps or naturals and they just ‘happen’ to fall consistently on what might appear to be the dominant scale degree, you are almost surely in minor! For example, ‘C major music’ with lots of “G#s” is likely to be ‘A minor music’ in reality.)

Second, when connecting the subdominant and tonic, one must avoid writing melodic augmented seconds in a “6-7-1” melodic line. This situation calls for the use of the ascending melodic minor scale. The same issue can arise in connection with the supertonic. Details of usage of the alternate forms of these chords were also given. If any of this seems unfamiliar or hazy, you may wish to review Part One.

- Grand Staff Templates | Free Blank Sheet Music

Free blank grand staff templates in portrait and landscape orientation in PDF format.

On a larger scale, this discussion of part-writing in minor keys follows previous articles on part-writing tonic and dominant; the subdominant; the supertonic; and the mediant and sub-mediant triads. All along the way, important concepts have been introduced—concepts assumed to be known prior to reading this Hub. So it may be advisable to go back further yet! There is a list of the concepts and Hubs at the beginning of Part One which you may wish to check out so you can better decide whether to proceed or go back. Some of the concepts include principles of spacing and doubling; parallel perfect intervals; resolution of the leading tone; similar fifths and octaves; and principles of chord succession.

If you do decide to go on, know that the most productive way to use this Hub is to work through the practice questions—don’t just read the answers! Best is to actually write them out by hand; as always in this series, I provide a link to printable staff paper for your convenience in doing so.

The Submediant

The submediant triad in minor can take the form of either a major or a diminished triad; the second possibility creates a similar difficulty to the one experienced in dealing with the supertonic in minor. It is not quite as severe, though, since the normal form of the submediant is the major triad, not the diminished. In fact, it’s fairly rare to see (or hear!) vio. We’ll defer dealing with it for now.

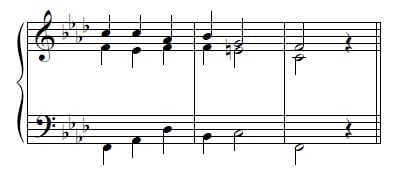

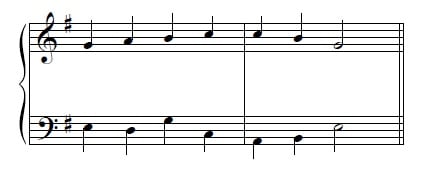

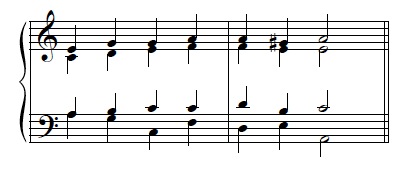

VI—often written as bVI for complete clarity that the triad is built upon the lowered sixth scale degree—luckily provides little additional challenge in part-writing. The only caution is that the progression bVI-ii is better avoided; it implies the awkward leap of a diminished fifth in the bass. Write bVI-iv instead:

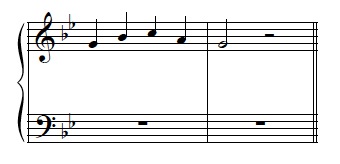

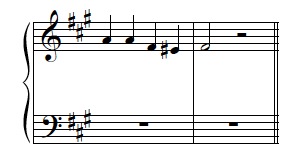

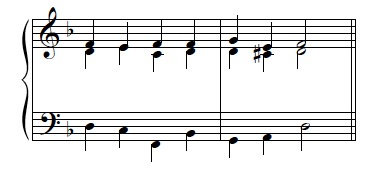

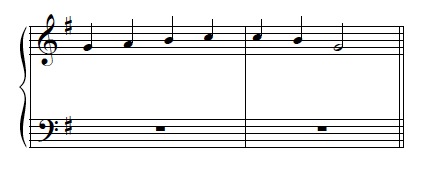

Try a couple of practice versions. Begin by identifying key and scale degrees of this soprano:

- Grand Staff Templates | Free Blank Sheet Music

Free blank grand staff templates in portrait and landscape orientation in PDF format.

Since we know this Hub is about minor key examples, we can infer that this is not Bb major, but G minor. The scale degree numbers of the line would then be 1-3-4-2-1. Harmonize it with the progression above—i- bVI-iv-V-I, and begin your bassline on the upper “G.”

(As always in this series of Hubs, you can see lines added successively, usually in the sequence bass, alto, tenor. But you will get the most out of the exercises if you work through the harmonization yourself on paper first. If you didn't already print some manuscript paper out, the link is repeated at the right.)

Taking the tenor down to a “D” in order to make the final tonic triad complete would be perfectly acceptable, and is a choice frequently seen in music. Here the incomplete voicing is chosen because it avoids the lowest part of the tenor range, resulting in a stronger and brighter chord color. But one might prefer the opposite in some musical contexts.

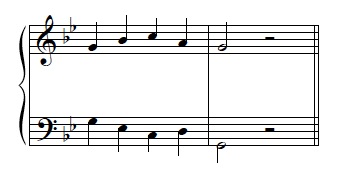

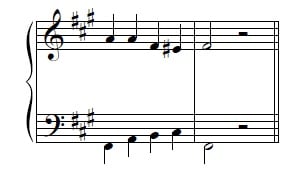

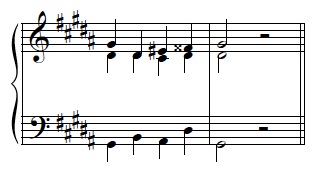

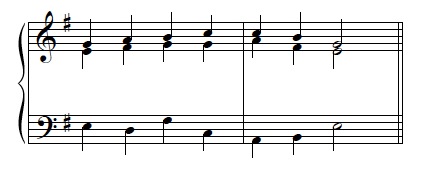

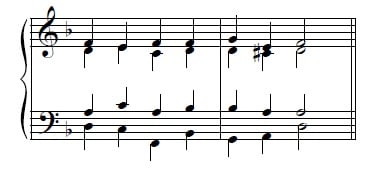

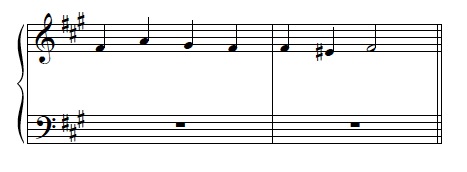

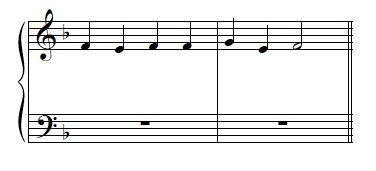

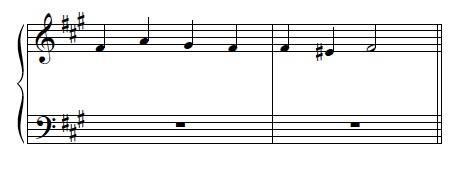

Let’s try another question. Characterize this soprano as usual:

This line could only be minor mode. In B minor, the line follows a 5-6-1-7-1 pattern. Harmonize it, using the same bass line given in the preceding example—appropriately transposed to B minor, of course! End with an open-spaced chord.

There is an alternate possibility ending with a close-spaced chord: the alto and tenor could both leap upward by a fourth when moving to the third chord of the sequence. This would give a slightly brighter sound.

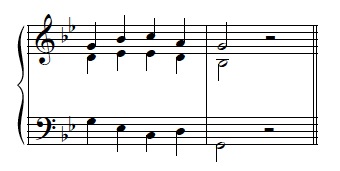

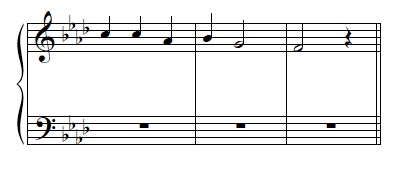

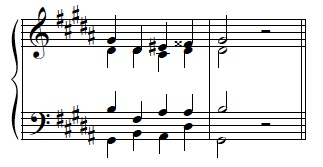

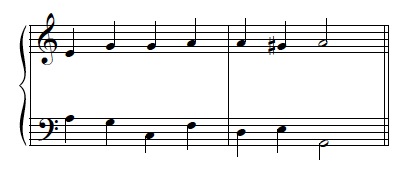

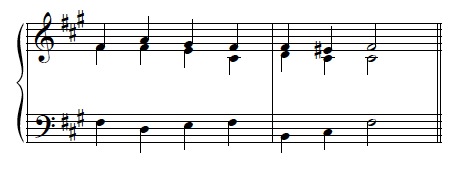

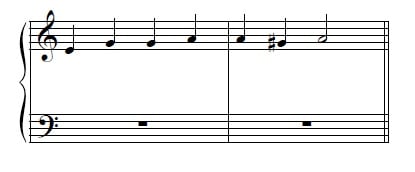

Let’s do one final exercise with this chord progression. First, characterize the soprano as usual:

This A minor soprano outlines the tonic triad via a 5-1-1-2-3 line. Add a bass line, beginning it with a low “A”; think carefully about how this choice affects the bass line overall. (In musical “thinking”, it’s often helpful to physically sing or play the line in question. What does your musical intuition tell you when you do so?)

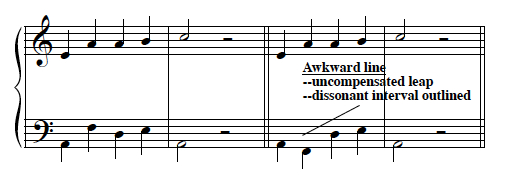

The low “A” eliminates the bass lines we have used previously, since an exact transposition would take us below the bass range. Therefore, we will need to leap to a higher octave at some point in the line. But where? It must be before the “D”, since that is the note which would be too low—and that means that we can either leap upward in moving to the second or to the third chords. Is one better than the other? Here are the resulting choices:

As shown, the first version is better. The second one creates a very awkward line which breaks two melodic ‘rules’—first, a large leap is followed by motion in the same direction; traditionally, such a leap would be balanced by motion in the opposite direction. Second, the extreme notes of the line—the low “F” and the high “E”—outline a dissonant interval, which tends to be subtly (or not-so-subtly) bothersome to the ear. By contrast, the first line is much more logical, and much easier to sing.

Now supply the alto and tenor voices.

Note how the common tones in the alto and tenor help to ‘anchor’ the leap in the bass; the overall effect is quite smooth.

The mediant triad (III)

The mediant triad’s two forms are major and augmented. The augmented triad consists of two stacked major thirds, which means that the fifth spanning the root and fifth of the triad is not a perfect fifth, as in most triads, but a (dissonant) augmented fifth—thus, the triad name. Because of its dissonant quality, the augmented triad, like the diminished triad, is not traditionally used in root position. As with vio, then, we’ll defer dealing with the augmented form of the mediant.

There is an oddity about the mediant in minor: for pretty much all other non–tonic minor chords, the harmonic minor scale offers reliable guidance as to which form to use as ‘default;’ but not so the mediant. According to the harmonic scale, we should generally write the augmented form, which uses the raised seventh scale degree. The mediant, however, is more likely to appear in its major form, with the lowered seventh.

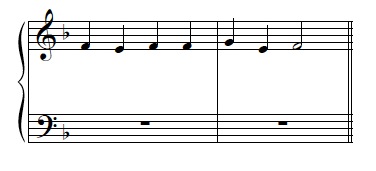

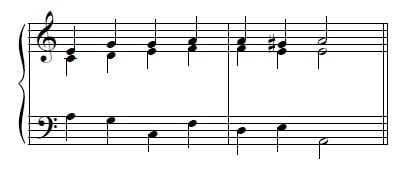

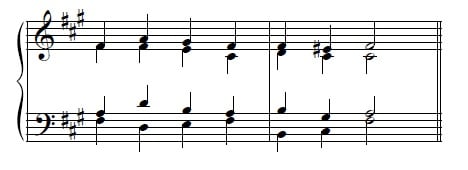

Here are a couple of uses:

Example 6a is reasonably typical. As in all cases where we have two consecutive instances of root motion by second, care in part-writing is called for. The III-iv transition follows the ‘parallel thirds’ voice-leading, while the iv-V voice-leading sees the upper parts move contrary to the bass.

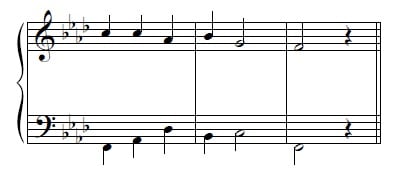

Let’s practice using the mediant.. First, what is the key and scale pattern of the soprano below?

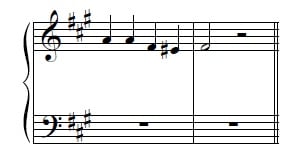

In F# minor, we have 3-3-1-7-1. But which model can we use? That will determine the bass line. See if you can figure out which one fits.

Rhythmically, the progressions from Example 6a and 6b fit. Only the third chord differs, so the third note is the one to look at. It is decisive: scale degree 1 fits the subdominant, but not the supertonic, so Example 6a is the model to follow.

Now supply the inner voices.

Soprano pattern?

In F minor, we have 5-5-3-4-2-1—clearly, one of the versions from Example 7. Since both versions share the same chord progression, we can go ahead with the part-writing. Begin with an open-spaced chord.

Key and scale degrees?

The key is G# minor; the scale degree pattern, 1-5-6-7-1. This is quite close to one of our models. Harmonize it, beginning with a close-spaced chord.

It would also have been possible to begin with an incomplete tonic chord.

A new possibility

You’d think, from what has been said so far, that of the two forms of the triad built upon the seventh scale degree, the diminished form ‘predicted’ by the harmonic minor scale would be the norm—and you’d be right to think so. We won’t deal with this possibility just yet, for the same reason that we have sidestepped all other diminished triads.

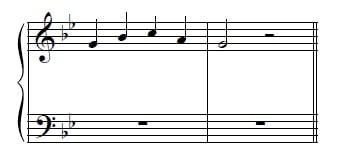

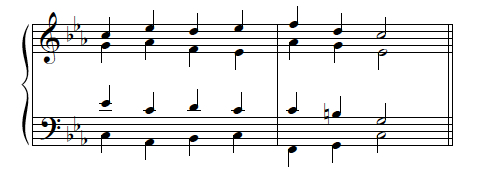

Yet there is a colorful and not-so-terribly-infrequent alternative form in minor. Instead of the normal diminished chord viio , the major chord bVII may be built upon the lowered seventh scale degree. This ‘lowered seventh’ chord available in minor has a unique name of its own to distinguish it from the leading-tone triad: it is called the “subtonic.” This special name acknowledges a radically different harmonic function: whereas the leading tone triad functions as a dominant, the subtonic does not. Instead, it is frequently found in association with the major mediant that we were discussing above:

Notice how the color near the beginning of the progression has a ‘major’ sound—this is not surprising when we consider this progression closely. To understand this fact better, we need to take a sidestep into scale theory for a moment.

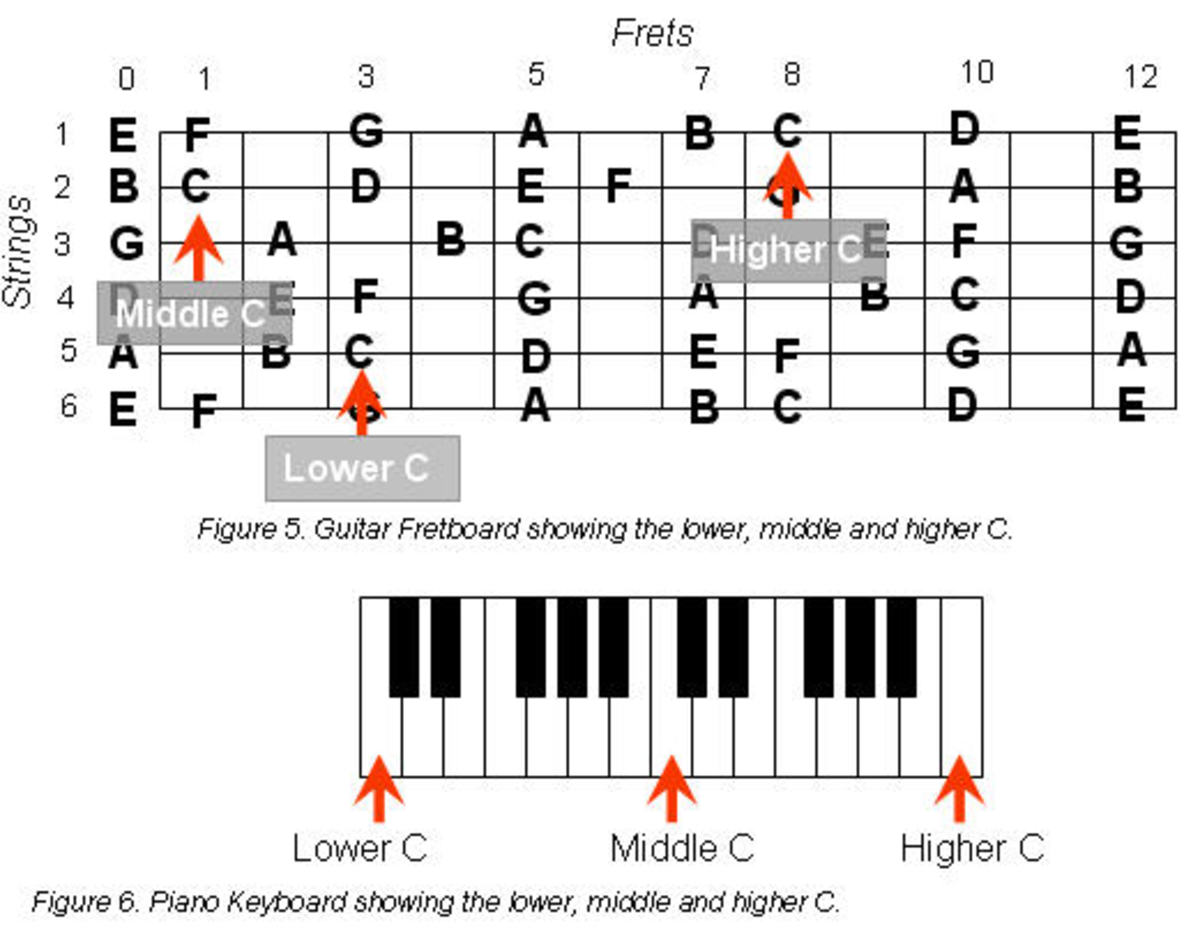

Consider our key: C minor shares a key signature with one, and only one, major key—Eb major. This relationship has a name: C minor is said to be the “relative minor” of Eb major. (Conversely, you could say that Eb major is the relative major of C minor.) It’s one of two common ways of finding correspondences between major and minor tonalities: the other case was that of the parallel minor and major, mentioned above—they have different key signatures, but share the same tonic.

Bearing this relationship in mind, we can find some logic to the ‘major’ sound at the beginning of Video Example 13 which we noted above. The Bb toEb part of the progression would be V-I, if we were in the relative major key (Eb)! Thinking of it this way, we would surely expect it to sound major—as it does.

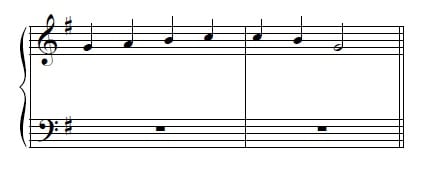

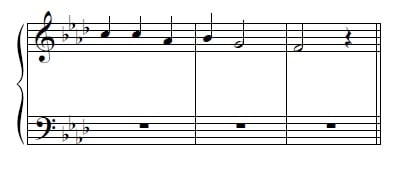

Try part-writing a couple of examples of this ‘circle of fifths’ progression. As always, start by characterizing the soprano according to key and scale degrees.

This is E minor—though if we didn’t know it is supposed to be minor it could easily be taken for G major, the relative major to E minor. Harmonize, using an appropriately transposed version of the bass line in Example 11. Suggested tweak: take the third note of the bass line down an octave. Why is that arguably a bit better?

The original bass line outlines a dissonant minor seventh (“Eb”-down to “F”.) The octave change eliminates this, making the line a bit easier to sing, and a bit more effective musically. Implementing the same fix in the example would require taking the bass down to low Eb, which is below the prescribed range. In this key, though, the lower octave would be a 'G', which is not out of range.

How about this one?

In D minor, we have 3-2-3-3-4-2-3. Harmonize it, beginning with a close-spaced chord—but be careful; there’s a trap in the second chord. Can you spot it, and figure out a strategy to avoid it?

As shown, the second chord has no fifth; both root and third are doubled. This avoids parallel fifths, which are otherwise nearly unavoidable if you start with the chord directed.

Let’s try one last example of the ‘circle of fifths’ progression using the subtonic. Key and scale degrees?

We’re in A minor, and the line is 5-7-7-1-1-7-1. Harmonize, beginning once again with a close-spaced chord.

Did you figure out the unison doubling of the tenor and bass? Some students of part-writing tend to think there is something wrong with such a unison doubling, but in reality it is not unusual at all to double adjacent parts in this way.

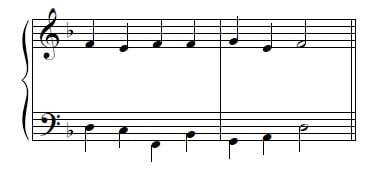

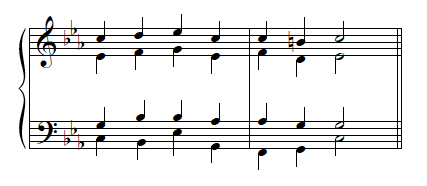

There’s another progression involving the sub-tonic that’s worth a mention, although it’s more characteristic of popular styles than of common-practice tonal music. In this progression, a scale-wise motion in the bass leads upward to tonic: bVI- bVII-i. In this example, the progression is paired with a i-iv-V-i.

It’s interesting to observe that the soprano and bass mirror each other in the first measure; where the bass descends by step, the soprano ascends by the same interval.

Here’s a practice question for that progression:

It’s a 1-3-2-1-1-7-1 line in F# minor. Harmonize according to the model given.

Doc Snow on Wordpress!

- snowonmusic | A music theory blog that's NOT all work!

What do Sting and Johann Sebastian Bach have in common? snowonmusic.wordpress.com--but just why, you'll have to find out there!

Fairly straightforward to part-write!

To sum up, here are some quick hints and guidelines for part-writing in minor keys:

1) Check your leading tones! Are they raised where they need to be?

2) Check the vicinity of those raised leading tones—have you approached them from lowered sixth scale degrees, creating an objectionable augmented second? Worse, ‘resolved’ them to lowered sixth scale degrees? (In the latter case, you probably shouldn’t have raised the leading tone.)

3) Use the harmonic minor scale to help you remember that most minor chord containing the sixth scale degree use the lowered sixth, while most containing the seventh scale degree use the raised seventh. The primary exception is the mediant—most often this triad uses the lowered seventh scale degree for its fifth, not the leading tone. Also, the use of the subtonic triad, while quite a bit less frequent than the leading tone triad, is not rare.

And that’s it for this Hub—and for part-writing with triads in root position. But there’s much, much more to be said (and practiced) about part-writing. There’s a big, wide wonderful world of harmony using inverted chords—a world of much more sophisticated, expressive, and flexible harmonic language. Continue this series of Hubs to learn to deal with them!

Other Hubs by Doc Snow

- Part-writing Chords: Summary I

A 'syllabus' and summary for Doc Snow's innovative Hubs on the essential musical skill of part-writing. Sequence, content and links--plus a summary of part-writing 'rules.' - Part-writing Inverted Chords: Primary Triads In First Inversion

How to use inverted triads in common-practice four-part writing. Learn to write tonic, dominant and subdominant in first inversion--these explanations, illustrations, and practice examples make it easy! - Strange Days Again: Remembrance And The Doors' Sophomore Album

Music and memory intertwine: The Doors' most innovative album, "Strange Days," analyzed and remembered. What it was, is, and why it mattered so much to me. - "Crystal Waters": A Meditation

Remember the Gulf oil spill? Probably not, unless you live there. There, the consequences still play out. Here's two reactions. Read, listen and remember.