Rear Window Maestro

In the movie Rear Window, suspense virtuoso Alfred Hitchcock orchestrates beautiful tension into the seemingly prosaic, combining murder and uncertain love - both of which need to be proved - to create one of his most thrilling fright films. The camera moves gradually across the living room of a small, New York City apartment during a heat wave. The unease begins as we see Jimmy Stewart seated in a rather tormenting position with one leg propped up and bound in a full, plaster cast - beads of sweat dripping from his brow as a result of the intense, summer heat.

A thermostat, one of those items that only a bachelor would keep in his living room, comes into focus and inches up toward one-hundred degrees. The camera then continues panning around the disheveled room to reveal assorted treasures belonging to this thrill-seeking character, L.B. “Jeff” Jefferies, photographer. His living room objet d’art include photographs of adventurous scenes, a broken camera – the corollary of Jefferies’ broken leg, a black telephone circa 1950’s, scattered travel-memorabilia and a provocative, if distorted, portrait of a woman – but the photograph is in negative, thus showing a ghostly figure within a sepia-tinged background. All of these clues are displayed before the light of a big, picture window which looks out on a back courtyard and the apartment windows of people living in the same brick and mortar, urban complex.

For Hitchcock, it is all in the camera-work. James Stewart was quite possibly the best actor for understanding Hitchcock’s motive. Stewart employed deftly-hewed facial expressions that seemed so natural, using his eyes to convey thoughts and emotions. In Rear Window these talents were showcased, as his character was planted, for the duration of the film, in a wheelchair.

Had this film been directed by almost anyone other than Hitchcock, the story would simply have been about a man with a cast on his leg sitting in a wheelchair in the small, dreary living room of his New York City apartment obsessively peering out the window, sometimes even with binoculars, spying on all of his neighbors. However, since the man with the broken leg is the iconic James Stewart whose familiar face jazzes up the screen, all voyeuristic implications can be rationalized to psychological-study or mere people-watching. Stewart and his esteemed presence dashes any hint of creepiness, or nearly so, and makes snooping justifiable.

In many ways this is a voyeur-film, and with his superior touch, Hitchcock magically portrays it as art, a fashion statement and a thrilling murder mystery. Captured in low light and thus furnishing a sepia-feel to the towering, brick topography of an implied urban setting, Paramount studios was the actual venue for the director’s brilliant stage-craft. At first glance, one is not sure whether this is really New York City or a well-wrought stage setting. Indeed, the uncertain verisimilitude of place contributes greatly to the artistry of the film. Is this a film or a play? The tentative answer provides an edgy mood to an already engaging tableau.

With its singularly subjective point of view, the action is seen through Jefferies’ eyes; he watches from his window the energetic, scantily clad, blond dancer, Miss Torso, as she swivels about, unaware of her watcher, to music which drifts across the courtyard. Another brilliant effect is the echo-chamber of sound caught within the piazza of the tall, brick apartment buildings. Voices heard but words not quite made clear - captivating music of almost familiar scores rendered tinny and mutated add eerie suspense. These background tunes were actually popular songs of the era by such artists as Bing Crosby, Dean Martin and Nat King Cole. They lend a distantly sweet yet pedestrian milieu.

Intermixed with the magnificent musical scores of Leonard Bernstein, the atmosphere shifts from prosaic to epic. The camera pans from Miss Torso’s ballerina-esque plies and leg-kicks to an adjacent apartment where a bridegroom steps over the threshold of his new apartment, bride in his arms and before kissing her draws the shade down upon Jefferies’ gaze. Jefferies watches with perfect response-expressions, and we the audience are privy to both the couple and the watcher. Now, the voyeuristic milieu creeps in and is gradually yet strongly felt.

Hitchcock uses panning and close-up camera angles to create this watchfulness in close proximity. Jefferies’ solitary occupation which, like a telescope, cannot be seen back into renders, very quickly, a psycho-sexual theme at close range. Jefferies, the watcher, is oddly not seen by any of the neighbors. Thus, the first one-third of the film entraps the audience in this voyeuristic web, with only glimmers of beauty in perhaps Stewart’s baby blue eyes or the fleeting glimpse of a woman’s dress swishing across the room beyond a window frame.

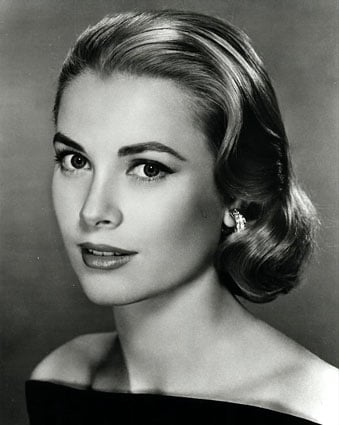

Enter Grace Kelly to finally glamourize the film. The lovely Lisa Freemont, Jefferies’ socialite, fashion-model girlfriend, breezes into the brown-hued apartment in an Edith Head gown that seems to float like a sun-filled, cumulous cloud and, interestingly, resembles a ballerina dress. Hitchcock once called Grace Kelly a “snow-covered volcano”, all fiery emotion underneath the blond pallor of diamonds or ice. The director most certainly conjured the image lovingly for it is rumored that he was in love with his favorite actress. Grace Kelly only made a hand-full of films, three of which were with Alfred Hitchcock, before she settled down to family life, marrying Prince Rainier of Monaco and thereby outdoing the regal image that her poise and beauty always conveyed. She portrays the perfect combination of elegant sang-froid, chic-smarts and feminine vulnerability to have her audience in the palm of her hand and thereby terrified when the heroine’s life becomes in danger.

We, the audience, are accustomed to Jimmy Stewart playing the farcical buccaneer who would forfeit love for adventure as in, It’s A Wonderful Life, or the polished publishing man as in, Bell, Book and Candle, but Jefferies appears ludicrous indeed to waver for an instant before the lovely and adoring Lisa. Yet, he is struggling to get at the core of things. The couples who live across the way, oblivious of the watcher’s gaze, mimic the conventions of love and marriage which Lisa so passionately desires and Jefferies so vehemently distrusts. This setting provides a microcosm for Jefferies’ visions of life beyond bachelorhood. The melodramas played-out before him conveniently feed into the adventurer’s most sordid and feared suspicions about marriage.

Meanwhile, as Jefferies and Lisa dance the proverbial dance of couples who are at a turning point in their courtship, a murder may have taken place in an apartment across the way. In keeping with the classic Hitchcockean trope, Jefferies must unravel the mystery and save his own face as well. Moreover, Jefferies has the daunting task of convincing his friends that a murder has taken place and that he is not just a peeping-Tom letting his imagination run wild as he convalesces in his wheelchair. And he needs to enlist his friends’ help in solving the alleged crime.

Argumentation ensues to prolong the suspense, at which point questions of ethics and themes of loneliness, voyeurism and morbid curiosity come into play:

“We’ve become a race of peeping-Toms. People ought to get outside and look in at themselves,” says Stella, a nurse, played by Thelma Ritter.

When Lisa would rather be making love than peering through windows, she argues rather dismally, “I’m no expert on rear window ethics,” to Jefferies just before the terror goes into full-gear.

The film was written by John Michael Hayes and inspired by Cornell Woolrich’s short story of 1942 which was loosely based on Life photographer Robert Capa. Filmed with a 35mm camera, Rear Window, (1954), received four academy awards for Best Director, Best Screenplay, Best Cinematography-Color and Best Sound Recording.

Additionally, writer, John Michael Hayes won the 1955 Edgar Award for Best Motion Picture.