Text 2 Film: Part 3 - The epistemology of adaptation

Since I've talked a little bit in previous hubs about some of the concerns that people have to deal with when adapting a previous work of literature to the screen, I'm now going to give you a simple look at my own view of the difficulties of adaptation.

In both literature and film, there are three primary features that are used to tell a story.

In literature, these three features are:

- Dialog

- Events

- Episteme

In film, these three features are:

- Soundtrack

- Visuals

- Timing

The three features for each are slightly different though they do overlap a little, and the difficulty lies in trying to adapt those sections where they don't overlap to fit the constraints of a completely different medium.

But first, let's explain what I mean by each element.

(And keep in mind that I'm trying to illustrate the difference between literature and film. That means I may be using films that were not adapted from a book and books that have never been adapted to film in order to make my point.)

Literature

Dialog

This one is pretty self explanatory. Your book has characters (unless you've decided to adapt a trigonometry textbook into a movie) and those characters likely say things. But on a related note, the world they inhabit also makes noises. There are birds chirping, cars vrooming, foreheads slapping, and cetera. So while these other sounds are not strictly dialog, the one feature that means the most here is the dialog itself.

Events

Again, this one is fairly easy to understand. Without things happening, your ability to tell a story is greatly hampered. So the author picks that story up out of the hamper and gives their characters stuff to do.This is both the characters doing stuff and the world they're in doing stuff to them.

Episteme

This one may take a little explanation. I use the term Episteme for lack of a better defined term. It comes from the Greek term for knowledge. What I would classify as episteme is basically everything that isn't covered in the first two, and even some that is.

The narrative voice is a large part of episteme. Whether your narrator is coming from within the story as a first person narrator or from without as a third person observer, what they say and how they say it will influence what you know and think about the story you're reading.

In the movie Throw Momma from the Train, Billy Crystal's character spends a lot of time trying to come up with a better way to describe a night than "moist" or "humid". In the end, Anne Ramsey, the titular Momma, points out the word "sultry". While they each can be used to describe the exact same environment, there's a distinct flavor to "sultry" that the other two just don't have.

So episteme basically means any knowledge that we're given about the story and characters that isn't coming directly from the sounds or events of the story.

For instance, in Brandon Sanderson's Alcatraz Versus the Evil Librarians, the story is being told by Alcatraz himself. He's snarky and sarcastic. That attitude won't change what happens in the story so much as it changes the way you think about those elements.

Compare that to the narrator for Harry Potter. In that instance, the narrator tries to be much more unobtrusive. But I would submit the Heisenberg principle of narrators. No matter how much your narrator tries to remain out of the story, there is nothing they can do that won't influence how that story is read. The narrator chooses what to show you and when. Which words to use to describe an environment or character.

Film

Soundtrack

This one includes more than simply music, which is what is traditionally considered a movie's soundtrack. This includes everything you hear on the soundtrack of a movie: music, dialog, foley and other sound effects.

Visuals

Again, this is pretty straight forward and broad. All sets used for the movie; all costumes tailored for the characters; casting of the actors; the performance of the actors themselves; movement and events; these all go into creating the visual look. Any time something appears on screen, there has been a decision made behind it. Sometimes the decision is that they don't care, but every filmmaker knows the importance of the visual look.

For instance, in The Sixth Sense, the decision was made to limit the use of the color red. Shyamalan was very specific about what he wanted that color to represent. Whether you noticed it or not, that one decision affected elements throughout the whole movie.

Timing

This one may seem unimportant but it's quite influential in film and is an element that literature has a hard time duplicating well. In both literature and film, events and dialog have an order. Even if that order is experimental and non-linear (as in Holes or Memento) there is an order at which those events are given to the reader or audience.

But timing is very much an element of film. And it's slightly different from what people mean when they say "pacing", though there's definitely an element of that present.

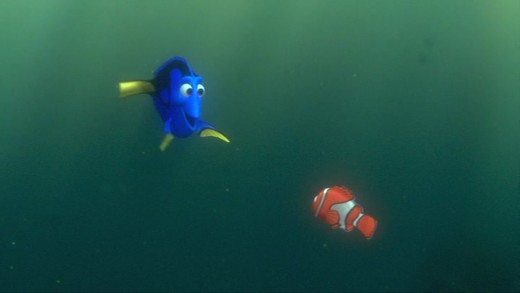

The film maker can control the specific rate at which events happen. And to illustrate the importance and unique ability of this element, I like to point to one scene in Finding Nemo.

After Dory and Marlin see what they believe is Nemo's lifeless body, Marlin gives up and swims away, leaving Dory alone. A very powerful scene, but I want to talk about something that happens afterward. She meets up with Nemo and swims with him for a while before finally remembering exactly why she was there in the first place. And that moment of memory is a perfect example of timing.

In the space of a few seconds, Dory remembers a series of quick flashes from previous scenes of the movie. They come faster and faster until the images are given just one frame each. But as fast as they come, the viewer can still make out many though not all of those specific scenes.

It's a flood of memory that can only be experienced in that way on film.

To try and describe that part in literature, there are two primary ways it could be done. Either the author could try to describe the scenes as she remembered them, one at a time, or they could simply write "A flood of memories."

Both methods would get the job done, but with very different results. Describing the scenes would stretch out the entire experience and reduce the immediacy of the event. And simply saying "a flood of memories" tells us what the character is experiencing but doesn't put the audience through the same thing.

So timing is very much an element of film.

Watch 2001: A Space Odyssey and tell me that Kubrick's timing isn't an element of that film.

Final Adaptation

So, after discussing what I mean with each of the three elements of both film and literature, the challenge in adapting literature to film (or even film to literature) comes down to transposing the elements of one into the elements of the other.

While the two formats mostly overlap in two out of three elements, episteme is largely a unique element of literature while timing is largely unique to film. Dialog can easily be put into a film and events can happen more or less as described in the book. But how do you take a sarcastic narrator and translate that into film?

In Frank Herbert's Dune, the episteme of the story is extraordinary: The narrator is omniscient, telling the reader all kinds of things that the characters can't know and there is a large amount of the story that happens in the minds of the characters.

In David Lynch's 1984 film, much of that episteme was turned into soundtrack, giving us voice-over narration of what the characters were thinking. In the 2000 SciFi channel miniseries, some was turned into dialog, some was left to the audience to interpret through the actions of the characters. Both decisions are valid, but the results are decidedly different.

But consider this. Have you ever read a novelization of a movie? I've read a few. And if the statement "the book is better" is to hold true, shouldn't the novelizations be uniformly superior? And if so, how come film novelizations aren't topping the charts in book sales all the time?

Because literature and film are different. If you read the book, you have an idea of how that story plays out in your head. And I will promise you right now that no film adaptation will match your version perfectly. Because you haven't had to adapt anything in getting the story from the book into your brain.

And the same goes for film novelizations. I've liked a few, but when you read one, the vision of the author still may not match the way you interpreted the movie on your own.

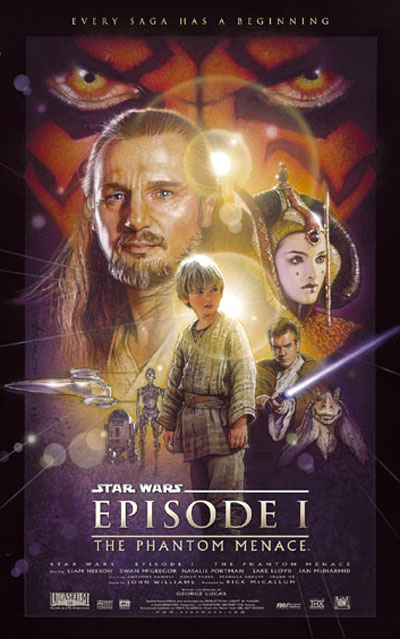

The novelization of The Phantom Menace was even done by the legendary Terry Brooks. And still I can't say it was better. There were elements that he did better because he's a professional writer and Lucas can't write dialog to save his life, but Star Wars is a visual experience. No matter how well Brooks does it, it's not the way Star Wars was meant to be enjoyed. And the story is not a Brooks story. He's been locked into the story that Lucas came up with.

The book was enjoyable. But it's just not the same.

But this is all mostly my opinion. What do you think?

Concerning literature to film adaptations, overall:

Also check out parts 1 and 2 in this series of hubs

- Text 2 Film: Part 1

A discussion regarding the difficulties that film makers run into and the decisions they must make when attempting to adapt a pre-existing text for the big screen. - Text 2 Film: Part 2 - The Chocolate Factory

A simple comparison of two versions of the same story. Everyone has a different idea and approach, but it's up to you to determine which is "better".