The Early Films of David Lynch

David Lynch is one of the most mysterious and innovative filmmakers in history. His influences range from surrealism to post-modernism. He has received three Academy Award nominations for best director, and to me he is one of the most thought-provoking directors in history.

David Keith Lynch was born on January 20, 1946 in Missoula, Montana. His father worked for the government, and as a result, the Lynch family moved from town to town in the Pacific Northwest (Olson 1). Lynch’s father worked as a research scientist for the Department of Agriculture, and he exposed his son to his work with trees and plants when he was a child (Lynch & Rodley 10). Many of Lynch’s films, especially his first few, reflect this interest in organic life specifically plants.

Painting had been an interest of Lynch’s ever since he was a child but, when he met Toby Keeler, whose father was a professional painter, he was introduced to the idea of art as a career. Toby’s father, Bushnell, gave him a copy of “The Art Spirit” by Robert Henri, which became his bible (Olson 10). After that, Lynch’s dedication to painting was unwavering.

His transition from painting to film occurred when he was a student at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia. He was inside painting when the wind blew through the window and shook the painting. He loved the way it looked and got the idea for a painting that moved (Short films of David Lynch).

Lynch new nothing about filmmaking, but he bought a 16mm camera and rented a hotel room. He mounted the camera on a dresser, and then he and his friend Jack Fisk constructed plaster casts of Lynch’s head and a background canvas to put behind them. Then, he projected one minute of looping animation onto the heads (Lynch & Rodley 38). The result is a four minute film of six human shaped figures changing colors and eventually vomiting out red liquid with a siren playing in the background to further emphasize their distress. He called it Six Men Getting Sick.

The film was originally projected onto the sculptured heads when it was screened. So it was more of a blending of sculpture and animation rather than a true film, nevertheless it demonstrates that Lynch was always drawn towards the disturbing and perverse, a trend that would continue in varying degrees throughout his entire career. His early films, like this one, tend to be more avant-garde than his later studio work.

Lynch always claimed that school and learning made him anxious and uncomfortable (Lynch & Rodley 32). In his own words “School was a crime against young people. It destroyed the seeds of liberty. Teachers didn’t encourage knowledge or a positive attitude (Hughes 10).” My interpretation of the film is that these figures are getting physically sick because of their schooling. This is a theme that continues in Lynch’s second film.

Despite the fact that the film won the Pennsylvania Academy’s Dr. William S. Biddle Cadwalader prize, it cost him 200 dollars which, to Lynch was too expensive, so he didn’t plan on making any more films. However, a wealthy man named H. Barton Wasserman, who had seen Six Men Getting Sick, offered Lynch 1,000 dollars to make him a similar piece, a sculpture that a looping film would be projected onto (Hughes 8).

He got an advance on the money and used it to buy a camera. There was a local store where Lynch found the camera of his dreams but the store was almost closing and he didn’t have the money yet. He asked them to hold it for him but they refused. So he figured he would have to get there first thing in the morning to be sure that no one else would buy it. However, Lynch had a great deal of trouble waking up in the morning, so he stayed up all night and went there at 8 am to buy the camera (Short films of David Lynch).

Instead of Lynch’s head being used as the model for the sculptures, this time it would be his wife’s, Peggy. His idea was to have a sculpture and a shower head, and then paint would pour from the shower onto the sculpture (Olson 34). However, when Lynch got the film back from being processed, he discovered that the camera had a broken take-up spool. So the film was just moving through the gate freely instead of frame by frame, making it just a blurred mess (Lynch & Rodley 39). Lynch was disappointed, but not angry and neither was Wasserman, who gave Lynch the remainder of the money despite the failure (The Short Films of David Lynch).

The inspiration for his second film came when his wife told him of a nightmare that her niece had, where she continued to repeat the alphabet over and over again in her sleep (The Short Films of David Lynch). The Alphabet is a blend of animation and live action. The film begins with a woman sleeping and becomes a nightmarish world full of bizarre animated scenes involving letters. The background noise was a recording of Lynch’s daughter crying. He was unaware of it at the time but the recorder was broken. The sound came out distorted but he decided that he liked it even better, so he used it (Lynch & Rodley 39).

As with Six Men Getting Sick, this film is about the difficulties of education and a child struggling with learning the alphabet. Lynch himself had trouble communicating with people early in life, his wife describes them as his “pre-verbal days” (Lynch & Rodley 32). This is Lynch’s first true film, and I find it to be very compelling. It is a subject that most people can relate to. We can all remember a time when, as a child, we hated school and learning.

A friend had told Lynch about a grant program with the recently established American Film Institute, and suggested he apply. The two requirements for applying were; a written script and a previous film. Lynch wrote an 8 page script and submitted it along with The Alphabet (The Short Films of David Lynch). Lynch expected the worst. He was up against several established independent filmmakers. However, one day at work he received the call from A.F.I. informing him that he had won the 5,000 dollar grant, and The Grandmother was born(Lynch & Rodley 43-44).

As with The Alphabet, The Grandmother was shot in his house. As he had done with The Alphabet, he once again painted the walls of his bedroom black for the film (Lynch & Rodley 48). This film also uses both animation and live action, like all of his previous work.

The film begins with an animated scene of a man and then a woman sprouting up from the ground like plants. Next we see a red droplet from the man and a white one from the woman combine to form a new figure that also sprouts up from the ground in the form of a boy. The parents are instantly hostile to their son, surrounding him and behaving like animals. Then, we cut to the family living in a house. The child is clearly being abused by his parents. We hear the sound of a faucet just before the child wakes up with a pool of orange liquid in his bed. He shows his father who reacts violently towards him. Eventually the child plants a seed in some dirt on a bed and waters it. A tree-like object grows and soon an elderly woman comes out in a process that resembles child birth. The two share an instant connection. At the family’s dinner table we get a further emphasis on the parent’s grotesque animal-like behavior as they stuff themselves with food. After that, the child has another abusive encounter with his parents as he attempts to go up the stairs. In an animated scene that follows, child fantasizes about killing them in a manner resembling the guillotine. After the boy and his grandmother share another intimate moment, ending in the two kissing, the grandmother then becomes ill, emitting a horrible screeching sound. The boy tries to enlist his parents help but to no avail, and the grandmother falls to the floor dead. The film concludes with the child appearing depressed and alone.

When I first saw the film I thought that the grandmother was the result of an incestuous relationship between the father and the son. Twice upon seeing the child wetting the bed the father abuses his son there. Later the seed that creates the grandmother is planted on a bed in a pool of dirt that resembles the urine. The birth of the grandmother clearly resembles childbirth. However, another possibility is that the child simply created the grandmother as a companion and incest was not involved. Either way this film clearly represents feelings of childhood fear and alienation.

Lynch admitted to being “really troubled” by things as a child, especially of the city, which will show up in Eraserhead (Lynch & Rodley 6-7). Also, he had a very close relationship with his grandmother while he was a child (Olson 45). Lynch’s own parents however, were very different from the ones that appear in the film. Upon seeing it they were rather upset, wondering what the source of all this distress had been. Regardless of his inspiration, this was a critical step in Lynch’s career.

The Grandmother was significant to Lynch’s future in three ways. First, it was his first narrative film. This marks the transition from more abstract experimental works such as Six Men Getting Sick. After this he would go on to make feature films, most of them with studio backing. Second, this is the first time he worked with Alan Splet, the sound director, with whom he would continue to work on his next four feature films. Finally, after seeing this film Tony Vellani, one of the A.F.I.’s founders, encouraged Lynch to apply to their film school in Beverly Hills, California (Hughes 12).

While Lynch was attending school at A.F.I. he wrote a script for a film he called Gardenback. It was based on a painting he had made. He found someone willing to finance the project, however, due to a dispute over the film’s content, he canceled the film and decided to make Eraserhead instead (Lynch & Rodley 58). He had a 21 page script written, for which A.F.I. gave him a 10,000 dollar grant. The production was scheduled to last for six weeks (Hughes 19). However, due to financial problems, it wasn’t until 5 years later that Lynch completed the film (Lynch & Rodley 55).

The film’s production would take place on an unused part of the A.F.I.’s estate. There was what had previously been a hay loft, stables and a few other abandoned buildings that Lynch took over for the five years of production. He was also, for the better part of that time, living in the stables because of his recent divorce from his first wife (Lynch & Rodley 60). The film’s low budget forced Lynch to cut corners wherever possible. Much of the material used to construct the sets was purchased from a company going out of business for only 100 dollars. He re-painted and re-used this material over and over again, and by doing this he managed to turn the hay loft into several different locations used in the film. They shot entirely at night because the land around the stables was used by the Parks Department and their equipment made too much noise to shoot during the day. The cast and crew were made up of mostly friends and fellow A.F.I. students (Hughes 19).

He was introduced to Jack Nance, the film’s lead, by a mutual friend. Lynch would go on to use Jack in seven other projects. His longtime friend Jack Fisk, who helped him sculpt the plaster heads for Six Men Getting Sick, played the Man on the Planet (Hughes 22). Jack Nance’s wife, Catherine Coulson, also played an important part in the film’s production, including handling the boom, operating the camera, and bringing food to the set. She was also cast as the nurse in a deleted scene where Henry and Mary go to the hospital to pick up their child (Lynch & Rodley 67). The film’s photographer was Herb Cardwell at first. However, because of the length of the film’s production and lack of finances, he left for other projects and was replaced by Fredrick Elmes, a fellow A.F.I. student (Hughes 19). Lynch would use Elmes again on Blue Velvet, The Cowboy and the Frenchmen, and Wild at heart (23). Alan Splet reprised his role from the crew of The Grandmother as sound director (12). The film’s small cast and crew, along with the length of time it took to produce, led to a sort of intimacy between them. This is perhaps why Lynch generously gave them all a cut of the film’s profits (30).

In 1974, while production on Eraserhead was all but stopped because of financial difficulties, Lynch was told by Fredrick Elmes that the A.F.I. asked him to conduct a screen test for two different types of videotape that they were looking to purchase. Lynch asked if he could use the opportunity to make a short film and shoot it twice, once with each of the video stocks. Elmes told him it would be alright and so Lynch shot The Amputee (Lynch & Rodley 66).

The two versions of The Amputee each run about five minutes and are virtually identical. It stars Catharine Coulson as a double amputee, who is dictating a letter in her head, which we hear via voiceover, while a doctor changes her bandages. The doctor is played by David Lynch (Hughes 14). The equipment he used didn’t allow for sync sound, so they had to dub everything in later. This was Lynch’s first experience with adding sound after the fact. Even such small productions as Six Men Getting Sick were shot with sync sound (15).

This is an important film for Lynch in two ways. First, The Amputee is his first film with dialogue. The Alphabet had a few lines spoken in voiceover, and the parents in The Grandmother spoke gibberish. However, this is the first time that one of Lynch’s characters has an actual conversation, even if it is with herself. Second, it shows that Lynch can tell a concise story with minimal means. Through the woman’s voice-over we get the story of her husband’s affair with her best friend. This kind of small scale production contrasts with Dune, which he made about 10 years later, when he had enormous resources at his disposal. Eraserhead’s production, while somewhat larger than The Amputee, also shows how a dedicated director with a vision can make a great film with limited resources.

Eraserhead was finally completed in April 1976, after four years of production (Hughes 31). It premiered at the Los Angeles Film Festival on March 19 1977, after another year of post-production work. (29). It was screened in its original 100 minute version, but was eventually cut down to 89 minutes by Lynch (27). The film only had a limited release but still managed to achieve quite a cult following on the midnight movie circuit. In fact, one theater is Los Angeles played the film every week for four years (30). Later on, with the success of Lynch’s TV series Twin Peaks, in the early 1990’s, Miramax re-released the film to theaters, giving it the major distribution it lacked the first time around, and allowed thousands more people to see Lynch’s vision on the big screen (25).

The film, and more specifically, its main character, Henry, was clearly influenced by Lynch’s experiences in Philadelphia. In 1967, Lynch married his then girlfriend, Peggy Reavey, when she got pregnant with his child. He was a very reluctant father, clearly uncomfortable with the arrival of an unexpected child (Lynch & Rodley 31). Henry has the same experience in the film. He is called over to his girlfriend’s house for dinner and is then told that she had his baby, and they must get married immediately. The child was apparently born premature, to further emphasize its unexpected arrival. Henry then takes the child home with him and has to deal with the difficulties of raising it.

The child that Henry fathered was incredibly deformed and grotesque. It had no arms or legs and an elongated oval shaped head with an eye on each side. It is probably the best special effect in the film, and to this day, Lynch has refused to reveal the secret of how it was done, so as not to spoil its magic. Some people theorize that it was made out of an animal fetus. However that is pure speculation (Schneider 8). The portrayal of Henry’s child in such a manner was probably influenced by Lynch’s daughter. While he was a loving and devoted father, as I said before, his wife’s pregnancy came as quite a shock to him and was not part of his plans (Lynch & Rodley 31). Additionally, she was born with two club feet (Hughes 26). These two things probably provided the source of inspiration for Henry’s child, although I’m not suggesting that Lynch views his own daughter in such a horrifying way.

Eraserhead’s bleak industrial setting was probably also influenced by Lynch’s time in Philadelphia. He was living in a previously abandoned three story house which cost him only 3,500 dollars. A child was shot in the street nearby, and the police chalk mark was left on the sidewalk for days afterwards. Also, he was robbed twice, his windows were shot out, and his car was stolen. However, the experience was not entirely a negative one, as Lynch says, “The area had a great mood - factories, smoke, railroads, diners, the strangest characters and the darkest nights (Lynch & Rodley 42).” Furthermore, when Lynch was living in Philadelphia, he was working at La Pelle’s, a printing company (Olson 39). Henry has the same job in the film. While, I doubt Philadelphia was quite as dreary as the world Henry lived in, it is a clear indicator of where his inspiration came from.

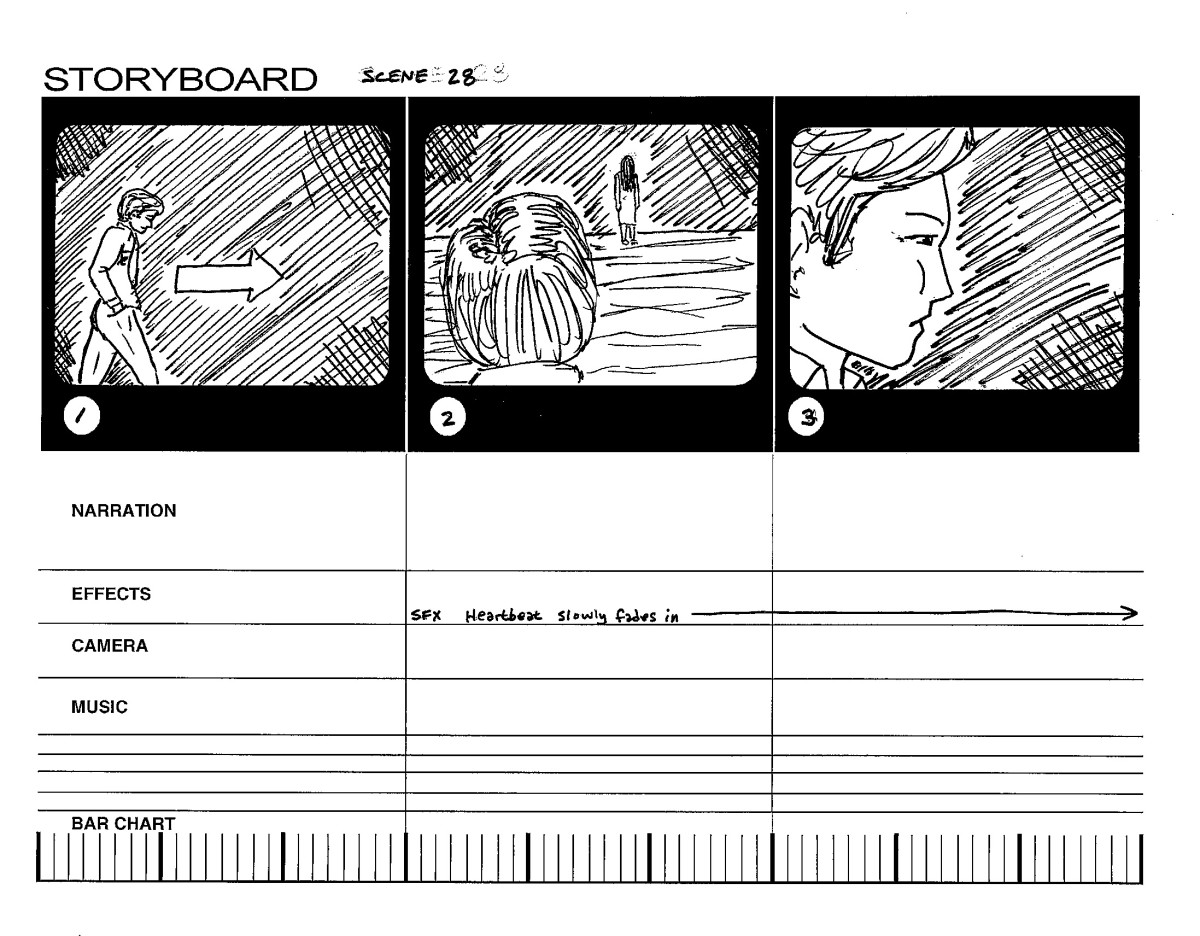

Another interesting aspect of Eraserhead is the Lady In The Radiator. She wasn’t in Lynch’s original script for the film. He got the inspiration during production. One night he just drew a picture of her. Then, he looked inside the radiator and saw a little space with what looked like a stage to him (Lynch & Rodley 64). The film’s original ending was for the death of the baby to result in the destruction of Henry’s world (Hughes 21). With the addition of the Lady In The Radiator however, the ending is a little more uplifting, as Henry seems to go to heaven. In fact, her role in the film seems to be to provide Henry with comfort from his otherwise bleak existence. It is appropriate then that she lives in a radiator, since its purpose is to provide warmth to people. Regardless of the inspiration for the character, I always found her to be one of the most interesting aspects of the film, especially the iconic sound that emits from the radiator.

Lynch has often said that 50 percent of his films were sound (Hughes 23). I think in Eraserhead it is even more than that. Alan Splet’s sound effects are what make the film great. Examples are the baby dogs getting fed by the mother, the sound of the elevator as it takes Henry up to his floor, and perhaps my favorite, the light bulb burning out at Mary’s house. The sound is essential to conveying the film’s dreary industrial setting. I think it is my favorite aspect of the film.

My favorite scene is when The Beautiful Girl Across The Hall comes over after locking herself out of her apartment. There is this great static sound in the background. The dialogue is great. She delivers each line with an eerie precision, and Henry has this great awkward reaction. It all combines to form what I think is one of the greatest moments in any of Lynch’s films.

After Eraserhead, David Lynch went on to work for Hollywood. He became one of the most critically acclaimed, sought after directors. His next film, The Elephant Man, was nominated for eight Academy Awards, including best director (Hughes 48). Lynch did not abandon his avant-garde roots, though. He almost always maintained creative control over his work, even in Hollywood. So his studio work, while perhaps not quite as abstract as his independent work, still has a very experimental edge to it.

Works Cited

Hughes, David. The Complete Lynch. London: Virgin, 2001. Print.

Lynch, David. Lynch on Lynch. Ed. Chris Rodley. New York: Faber and Faber, 2005. Print.

Olson, Greg. David Lynch beautiful dark. Lanham, Md: Scarecrow, 2008. Print.

Schneider, Steven Jay. The Cinema of David Lynch American Dreams, Nightmare Visions (Directors' Cuts). Ed. Erica Sheen and Annette Davison. New York: Wallflower, 2004. Print.

The Short Films of David Lynch. Dir. David Lynch. Absurda/Ryko, 2006. DVD.