The Grinch and Christmas may have a more complicated relationship than you might think

In 1966, Theodor Seuss Geisel put out one of his most well-known stories, "How the Grinch Stole Christmas," under the famous pen name Dr. Seuss. It's widely seen as a critique of the commercialism of the Christmas holiday that has developed over the years. If that's true—and there's a good case for that—I think that point is weakened a little bit by the end.

But we'll get to that.

The story follows a character named the Grinch who lives near the top of Mount Crumpit above Whoville where the Whos live. Kind of like how Americans live in Americanville and humans live in Humanville. And we all know and love that cute little girl, Cindy Lou Human.

The Grinch hates the Whos but especially their celebration of Christmas. He plots a scheme and schemes a plot to steal Christmas, and he even pulls it off for a moment before he realizes that the Whos still celebrate and sing even without the presents and trappings of the holiday. And in the end, the Grinch learns a lesson and returns the presents and everything.

It's a cute story that's great for kids. But if the point of the story is to speak out against the holiday commercialism, I think the story may have the wrong ending. After realizing that Christmas is about something other than the material goods that he's stolen, the Grinch's heart grows three sizes—a medical event that many a doctor should be concerned about during the holiday season—and learns to love the holiday.

But how does he save the day? He returns the gifts.

It's good that he wants to make things right. We all should have a desire to make amends for our past deeds. But if the point of the story is to say that we don't need the physical trappings of Christmas to celebrate the holiday, maybe you should let those trappings get lost for good and show it for real. Maybe the Grinch decides to give the presents back but on the way something else happens to them and they're destroyed, but the Whos forgive him anyway. That'd make the point.

Not that I'm saying Dr. Seuss got it wrong. Just that maybe—while it's definitely part of the message—the point of the story is less about commercialism and more about the personal redemption of the Grinch himself by realizing the true meaning of the holiday. And if that's the case, the triumphant return of the Grinch with the fruits of his sticky-fingered work is a wonderful ending, allowing him a full atonement.

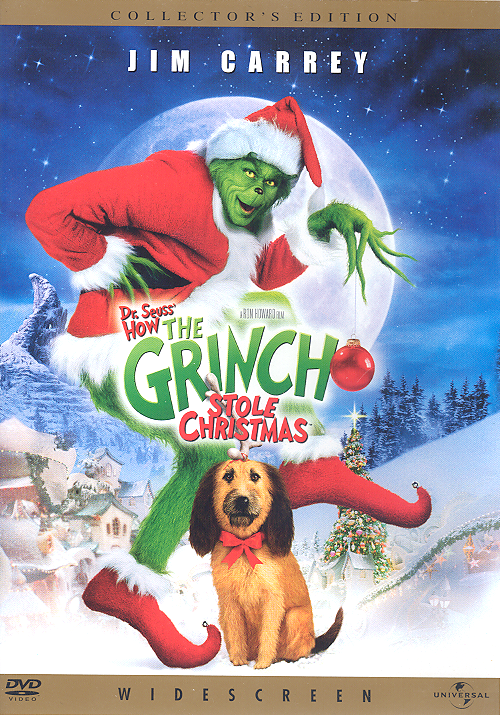

In 1970, Chuck Jones (a friend of Theodor Geisel) put out a made-for-TV, cartoon version of the story, narrated by Boris Karloff, that I'm sure most of you out there have seen. Again, in 2000, Ron Howard and Jim Carrey got together and put out a live-action, big screen movie. And while you can easily point out all the things they had to add to the 2000 version to make a full-length movie, I'd like to say that the differences in their endings really change their respective messages.

In the cartoon (as in the original kids' book) the Whos come out and immediately start singing. In the 2000 version, when the Whos wake up, all but a couple of them start milling around complaining that the holiday was ruined. It's Cindy Lou Who's influence that eventually causes them to realize that Christmas is more than the things they lost.

This sounds small, but here's the thing. In the 2000 version, there's a clear message that commercialism is getting in the way of the holiday, while apparently only a very young innocent and a curmudgeon cynic are able to see through that. And if that's the message, when the Grinch brings the presents back, that message is weakened because the solution to the story is apparently to bring the problem back.

In the 1970 version, while everyone down in Whoville clearly enjoys the trappings, they know Christmas is more and they still know how to celebrate and feel the Christmas spirit. And it's not the commercialism that ruined the holiday. It's the Grinch's inability to see beyond it that ruined Christmas for him and him alone.

Cynics like to feel that they are the only ones who "say it as it is", but that cynicism can get in the way as easily as it helps clear the view. And maybe all you're doing is ruining a great thing for you and you alone.

I enjoy both versions. The classic is great and probably half of the reason for the fame of the story itself. And while there are many additions to the story for the 2000 version—and many of those additions don't exactly feel Seuss-y—there are several points in the movie that actually get surprisingly touching.

For me, both versions get an 8 / 10.

The 1970 version by Chuck Jones is rated TV-G

The 2000 version by Ron Howard is rated PG for a couple mildly crude gags

- Christmas movies - what makes them classic and just how many of them do we need?

Christmas is coming. Which means a whole new batch of movies to tell you how to celebrate it. But what about all those Christmas movies that are already out? What made them Christmasy in the first place.