The Historical Value and Modern Relevance of "The Conspirator"

Did Mary Surratt deserve and receive a fair trial?

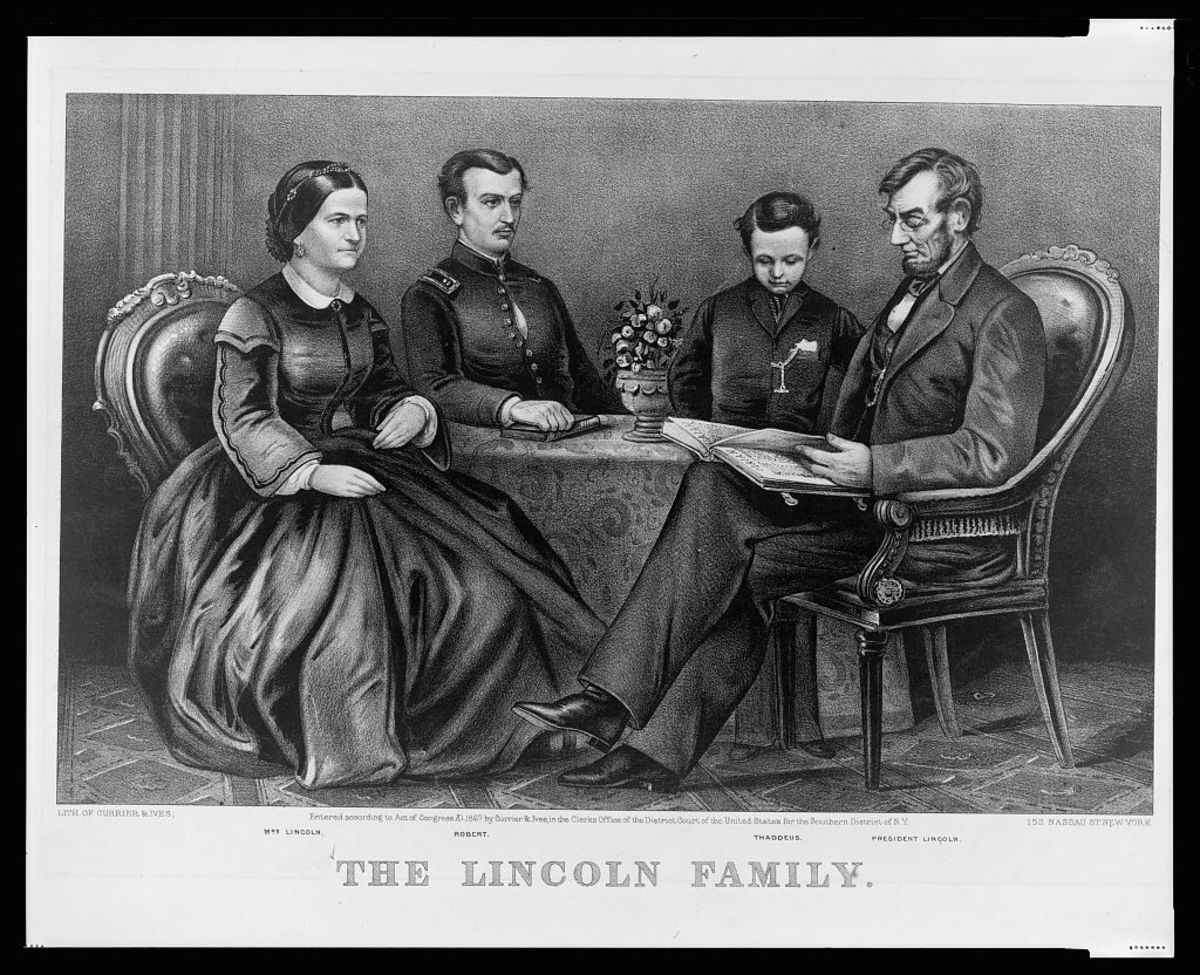

On July 7, 1865, Mary Surratt became the first woman to be executed by the federal government of the United States. She was convicted of being involved in a plot to kill President Abraham Lincoln, Secretary of State William Seward, and Vice President Andrew Johnson. And from the time that she was convicted and hung alongside three other men, controversy has surrounded her execution.

"The Conspirator," a film directed by Robert Redford and released last year, focuses on the trial of Mary Surratt and the initially reluctant efforts of Frederick Aiken, a young lawyer and ex-Union soldier in the Civil War, to defend her in court. But in the course of telling her story, the movie also covers very accurately - minus a few relatively minor details - many of the basic facts about the Lincoln assassination. These include, of course, a portrayal of John Wilkes Booth shooting Lincoln at Ford's Theater, his initial getaway, and his ultimate death in a Virginia barn. (David Herold, who accompanied Booth during his attempted getaway, is shown surrendering to soldiers shortly before Booth is shot.) But it also includes the lesser-known knife attack by Lewis Powell on Secretary of State Seward, along with George Azterodt "chickening out" and failing to carry out his part of the plot: killing Vice President Johnson.

The trials of Herold, Powell, and Azterodt, the other three to be executed in connection to the Lincoln assassination, are not shown at all in "The Conspirator." The cases against them were fairly cut and dry anyway, with their roles in the plot pretty clear. This film also leaves out the trials of four other men who were imprisoned as co-conspirators. Like Mary Surratt, their direct ties to the assassination were sketchy at best. But unlike Mary, most of these men lived long enough to have their cases reconsidered, with three of them receiving presidential pardons a few years later. (The fourth would have likely received a pardon as well, but he died in prison in 1867.)

So considering the circumstances, Mary Surratt is the most compelling figure among the conspirators, and her story is tailor-made for a Hollywood script. When her husband died in the early 1850's, Mary Surratt began renting rooms to boarders at her townhouse in Washington. And it was at this boarding house that many of the eventual conspirators in the assassination plots lived, visited, and/or participated in secret meetings. For Mary, the most important of these conspirators was her son John, who would ultimately introduce his mother to the famous actor John Wilkes Booth (among others). At the trial, several witnesses said in their testimonies that Booth had visited the boarding house on several occasions and was good friends with John Surratt, including particularly detailed testimony by an old friend of John's who had lived at the boarding house.

The beginning of the film, however, does not talk about Mary. Instead, it focuses on the character of Frederick Aiken, the man who would eventually have the unfortunate task of defending Mary in court. It begins with Aiken and a friend lying wounded on the ground in the aftermath of a Civil War battle. When medics eventually arrive to help Captain Aiken, he insists that they take his friend first. The film then jumps ahead to the day of Lincoln's assassination, with Aiken and his friends attending a party celebrating the Union's soon to be official Civil War victory. The horrible events surrounding the assassination are then depicted, with Aiken as devastated by these events as anyone.

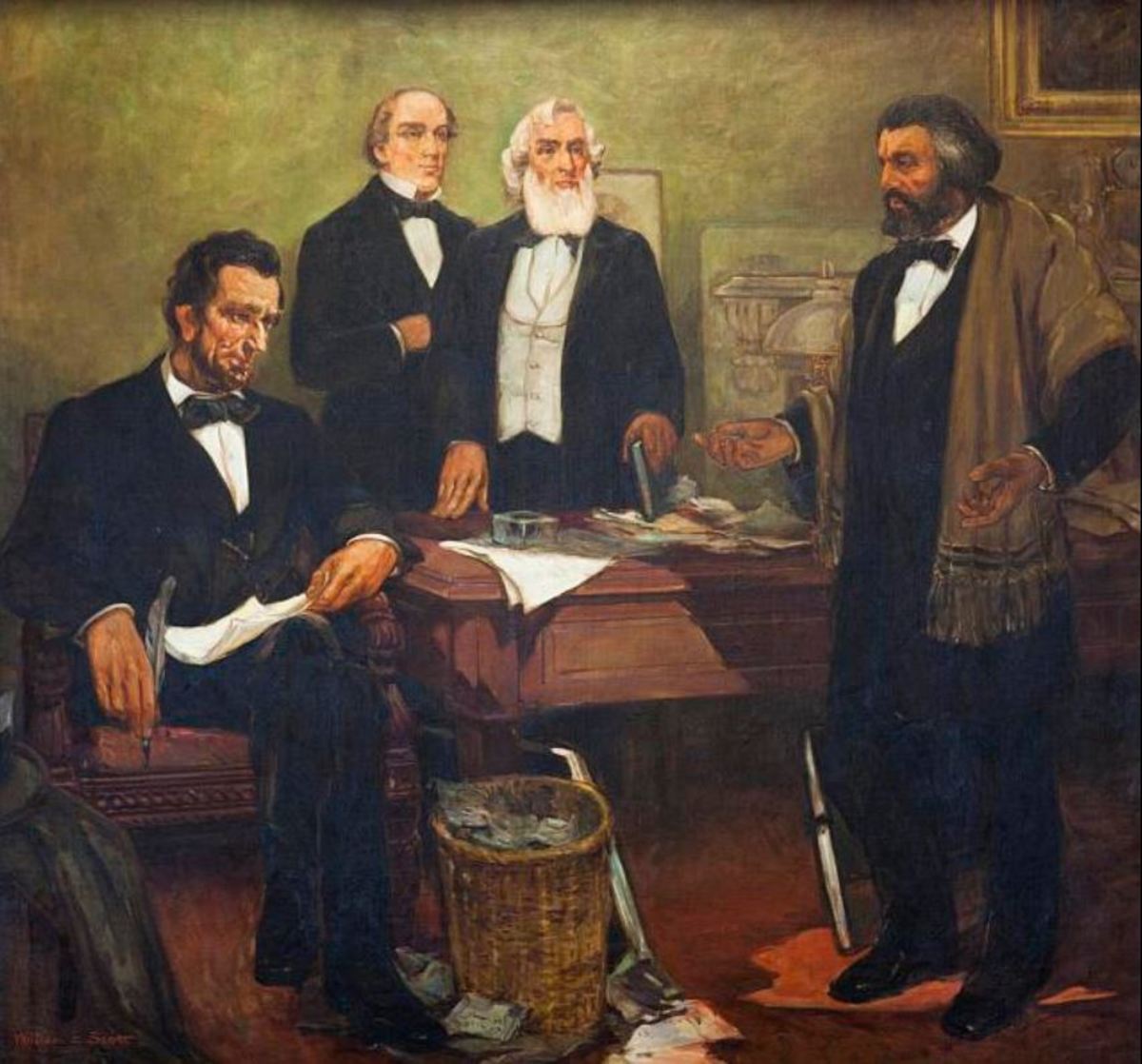

After the war, Aiken decided to practice law, and he was working for a Maryland senator, lawyer, and former Attorney General named Reverdy Johnson, who had taken up the case of Mary Surratt. Johnson was horrified by the fact that Surratt and all of the suspected conspirators were going to be tried by a military tribunal rather than in civilian court. But after making a passionate plea that this unconstitutional process should be halted, he realizes that this case could not be effectively tried by a Southerner. So he asks Aiken, a Union war hero, to take the case, and as might be expected, Aiken is horrified. How can he, a man who had fought to save the Union, defend this Southern assassin? Throughout the rest of the film, his friends, girlfriend, and superiors continually ask him the same thing, and the more that he ultimately digs into this case, the more his loyalty to the Union is called into question.

It is here that things get tricky historically. First of all, there is no way that a two-hour Hollywood film can cover all of the details that were brought up in the trial. (Nine witnesses, for example, testified for the prosecution, but only three were shown in the film.) But more importantly, historians do not agree amongst themselves as to the ultimate guilt of Mary Surratt. Did she know what her son and his various acquaintances were talking about in their mysterious meetings? Did she participate in some way in the carrying out of either the Lincoln assassination or of a previously botched effort to kidnap Lincoln and hold him for ransom in an attempt to free Confederate prisoners of war?

The movie does an effective job of not providing definitive answers to these questions. It does, however, strongly imply that she was a victim of injustice. Frederick Aiken, who was initially convinced of her guilt, becomes increasingly uncertain as the film progresses. He is frustrated with his client, and realizes from the start that she is withholding information. But he comes to realize that she is doing this in order to protect her son, who she admits (to Aiken) was involved in the earlier plot to kidnap the President. She insists, however, that her son is no murderer, even though she can offer no proof that John was not involved. (John Surratt had angrily left the boarding house shortly before the assassination.) Eventually, Aiken decides that the best defense strategy is to prove that John Surratt, not Mary, was the guilty party. Mary, however, pleads with him to not go after her son, with her strongest emotional outcry during the trial coming when her daughter Anna testifies against John.

Aiken's frustration with Mary, however, is not the main source of his anger. Instead, most of his fury is directed toward the handling of her trial. Right from the start, the military judges are portrayed as being heavily biased against Mary (and all of the suspected conspirators.) Every objection raised by the prosecution is upheld and of the defense is struck down, and the attitude of the judges toward Aiken is consistently disdainful. And worse yet, Aiken comes to suspect that two of the most damning witnesses against Surratt are lying, and even worse, they were coerced by the War Department into falsifying their testimonies. There were reasons to believe that these were pro-Southern men whose loyalty could be questioned, and they may have lied to save themselves. And when Aiken confronts Secretary of War Stanton about this, Stanton, according to the film, basically admits to it. But Stanton justifies his behavior by claiming that it is in the best interest of the country. In order to reconstruct the Union and prevent future insurrection, clear messages must be sent to both the North and the South: justice has been served, rebellion will not be tolerated, and the Union is once again secure. During times of war, security and unity must sometimes take precedence over due process of law.

In the end, the main subject of this movie is not the guilt or innocence of Mary Surratt. While it is unclear whether or not she deserved the gallows, she was definitely guilty of something. It is hard to believe, after all, that she was completely unaware of what her son and his friends were discussing at the boarding house. And if loyalty to her country were stronger than her loyalty to the South or to her son, she would have reported her suspicions to the authorities. But ultimately, her connection to the murder of the President comes down to which witnesses you believe.

But whether guilty or not, if the United States is truly a country based on constitutional principles, then she deserved a fair trial. And the fact that a person is accused of a particularly heinous crime is not reason enough to rush to judgment. Remarkably, in post-9/11 America, many of the same issues arose that existed in the aftermath of Lincoln's assassination. Is a military tribunal, with its less stringent requirements for providing evidence and assigning guilt, a constitutional process of administering justice? During a time of war, do security concerns outweigh individual rights? And if someone defends the rights of a suspected terrorist (or assassin), is this a sign of disloyalty? These questions are as relevant, controversial, and tricky to answer today as they were in the spring of 1865. Only in 1865, after the worst war by far in American History, the stakes seemed even higher.

Shortly after Mary Surrat's execution, the Supreme Court decided that the trial of American civilians by military tribunals was unconstitutional. But it was too late for Mary Surratt. It was not too late, however, for her son John. John had left Washington shortly before the assassination, and when he heard what happened, he fled to Canada. According to the film, Aiken was hoping that the imminent death of Mary Surratt might convince John to come home, accept the blame, and save his mother. John, however, would evade capture until 1866. The film ends with Frederick Aiken, who had quit practicing law, visiting John Surratt in prison. And as Frederick walks away at the end of the movie, a caption explains what happened to John Surratt. He was tried in a civilian court, and his trial ended with a hung jury. So the man who was probably the guiltiest Surratt ended up being released, and he died at the age of 72 in 1916. So if the movie is correct in arguing that Mary Surratt sacrificed herself in order to save her son, then I guess that she got her wish.