The Power Of Television

The Golden Age of Television & the Rise of Madison Avenue

America entered into an astonishing age of abundance in the 1950s. The invention of kitchen and household appliances freed women from housework for the first time. This freedom eventually led to boredom for some women, and they would launch the feminist movement in the next decade.

By 1960, virtually every American home had a refrigerator. Four million of them were purchased for $1.3 billion in 1955 alone. So many were sold that year because of the mass production of frozen food—old-style refrigerators had tiny freezers.

A revolution in advertising and selling kitchen appliances took place in the Fifties. It is best symbolized by the Lady from Westinghouse: Betty Furness. She had been a film ingénue whose career was winding down after thirty-six B movie parts.

At the age of thirty-three, Betty Furness was hired by Westinghouse in 1949 to star in television commercials. Soon, corporate America would come to understand the power of television to shape behavior.

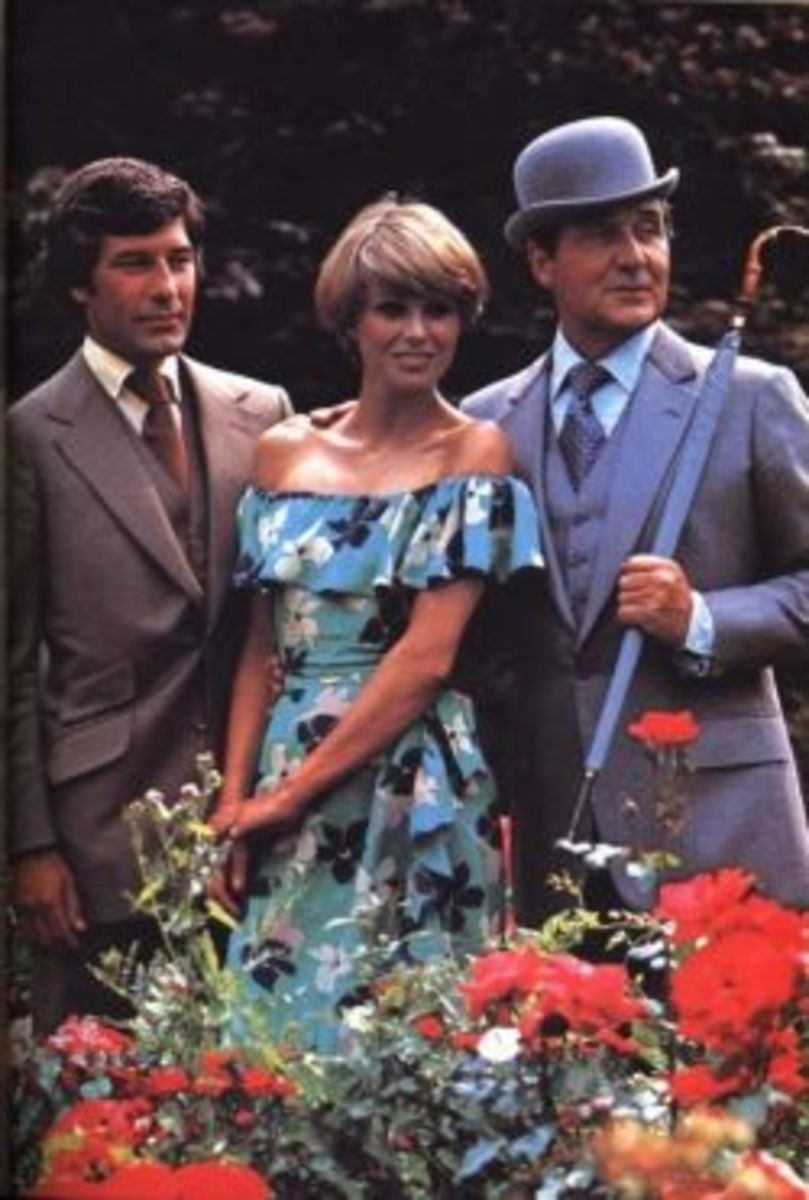

Betty Furness

Betty Furness was hired to deliver one three-minute commercial and two one-and-a-half-minute commercials on the weekly television drama series Studio One, for which Westinghouse was the lone sponsor. Her $150 a week starting salary was quite good for 1949. The commercials changed constantly and were aired live, meaning the lines had to be memorized.

Betty proved to be outstanding at her new job. She was attractive in a way that did not make women viewers jealous. Betty came across as bright, confident, upbeat, and modern—but not overly glamorous. She exemplified the all-American wife in an all-American kitchen: a sparkling new workplace that made household chores easy.

During the televised 1952 political conventions, she became a famous celebrity. Westinghouse bought nearly all the available airtime for commercials, and soon she was in America's homes more than twenty times a day for a week.

Betty intuited that her role was to keep viewers from leaving the room during commercial breaks. She determined to change clothes for each commercial to stay interesting and unpredictable. Housewives were glued to their sets to see what Betty would wear next. She wore her own clothes because she did not want Westinghouse to dictate her wardrobe—which was always neat and sophisticated but also modest.

The Lady From Westinghouse

The sales of Westinghouse appliances shot through the roof because of Betty Furness. Her trademark phrase was heard at the end of each commercial: "You can be sure if it's Westinghouse."

She began to be recognized wherever she went. Total strangers started to think of her as their friend. To them, she was just Betty—no last name was necessary since she had been in their homes.

In June of 1952 Betty pitched a new item, the $89 Mobilair fan. It was a large awkward fan, mounted on wheels, that could blow air in or suck it out. She didn't think it would sell, but the very day her commercials aired the Mobilair sold out in stores across America.

Betty was now the queen of American appliances and Westinghouse signed her to an exclusive three-year contract for $100,000 a year. She didn't know much about the machines except they were well made; they kept getting larger; and Americans loved them.

The only flop Westinghouse had that was presented by Betty in her eleven year run as spokeswoman was the dishwasher. Surprised and disappointed, Westinghouse commissioned extensive research that discovered women were afraid dishwashers might make them obsolete in the kitchen, and men might decide they didn't need wives.

The Mad Men on Madison Avenue

Revenues from television commercials totaled $12 million in 1949. By 1951 it was ten times that sum. Television could do what print ads and radio could never do: show the product being used.

Advertising men who worked in New York on Madison Avenue were pulling down $300,000 to $400,000 a year by the end of the Fifties—real money back then. The ad men referred to themselves as 'Mad Men.'

In his amazing 1958 book People of Plenty, Yale historian David Potter wrote: "Advertising now compares with such long-standing institutions as the school and the church in the magnitude of its social influence. It dominates the media, it has vast power in the shaping of popular standards, and it is really one of the very limited groups of institutions which exercise social control."

The power of television made the sizzle as important as the steak. Corporate budgets changed drastically as engineering and manufacturing took a backseat to marketing and sales.

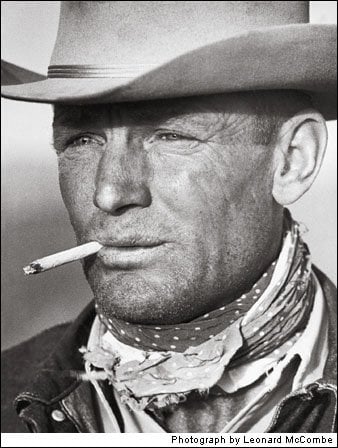

Enter the Marlboro Man

In 1954, the most influential magazine in the United States, Reader's Digest, published an article that for the first time alerted the public to a link between smoking cigarettes and dying of lung cancer. This could not have come at a worse time for the Philip Morris Tobacco Company. It had made a substantial investment in the launch of new filter-tip cigarettes for women called Marlboro.

Sensing that women might cut back on smoking, the company decided to push the Marlboro brand to men, too. But filter cigarettes had already been marketed as a woman's product—Real Men would never smoke them. Philip Morris hired the Leo Burnett advertising agency in Chicago to solve the conundrum because Burnett had become famous for inventing the Jolly Green Giant and the Pillsbury Doughboy.

To make Marlboro masculine, Burnett brainstormed what was the manliest symbol in America and decided it was the cowboy. The runner-up was the tattoo. Burnett also suggested turning the color of the package to a strong red. The first ad with a craggy-faced cowboy ran in 1955 and touted Marlboro's "man-sized flavor." It was an immediate and enormous success. Suddenly, Real Men DID smoke filter cigarettes.

The Power of Television to Influence Us

The power of television changed marketing forever. No longer was it about what people need but what they should want to keep up with their neighbors. No longer would Americans only purchase what was essential, what was necessary. From now on they would buy more and more luxury items—as seen on TV.

The new American would also break another taboo of their parents and grandparents: they would buy on credit. Automobiles were already available for ever-lengthening credit periods and the day would come when "buy now pay later" became an American mantra.

The task of the advertiser, according to one of the first and most influential motivational research experts, Ernest Dichter, "is to give moral permission to have fun without guilt."

Dichter was a pioneer in exploring the complicated subconscious psychological reasons by which people justify the choices they make. His research concluded that to persuade people to make the choice you want them to make you must "resolve the conflict between pleasure and guilt."

Dichter's theme is that when a new level of gratification is offered, it must be offered along with assuaging the target's guilt, what he termed an "offer of absolution."

My source for this article is the book The Fifties by David Halberstam.