To Sub or to Dub: The Challenge of "Translating" Films for Foreign Audiences

In January 2007, I went with a group of friends to see Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth, a dark fantasy set in Spain during the Franco regime. The film had generated a lot of buzz since its premiere at the 2006 Cannes Film Festival, and it had only just been widely released in the U.S. In our group, only my friend Rosanne and I knew that it was in Spanish. When the film began and the faun character began his narration, yellow subtitles translating his words along the bottom of the screen, I felt my brother shifting in his seat next to me. “This is in Spanish?” he whispered. There was a soft murmuring throughout the theatre as several other people realized that the film was subtitled. I was disappointed but not surprised to see some of those surprised people walk out within the first few minutes.

Pan’s Labyrinth went on to become the highest-grossing Spanish-language film in U.S. history. After seeing people walk out on the film because it was in Spanish, I began to wonder if English-speaking audiences are more resistant to subtitled films than other audiences around the world. Or is there a growing acceptance in the U.S. of foreign films? The mode of translation, subtitling or dubbing, plays a large role in the accessibility and success of the foreign film.

Foreign or Domestic: The Modes of Translating Films

Foreign films can either be subtitled (or “subbed”), with the translation shown on the screen, or dubbed, with voice actors speaking the foreign dialogue and attempting to match the mouth movements of the actors on screen. Each method has its advantages and disadvantages, and each approach to some extent alters the original text. An important difference between subbing and dubbing is whether the target audience is reminded of the film’s foreignness. With dubbing, the audience believes the illusion that the actors are speaking the domestic language. Subtitled films, on the other hand, remind the audience that the actors and language are foreign because the original dialogue and the actors’ voices are still heard. Even if the act of simultaneously reading the subtitles and watching the movie starts to feel natural, the viewer must constantly accept the foreignness of the film.

How do other countries manage it?

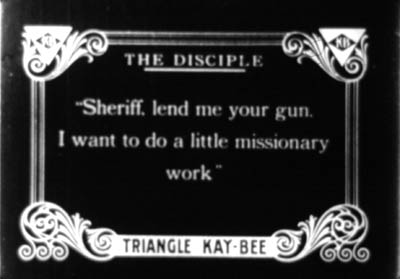

Europe, with its many languages among a group of tightly-clustered countries, has a long history of subbing and dubbing films. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, with the arrival of “talkies” (talking pictures), European countries had to choose a mode of translating foreign films.

Countries that speak French, Italian, German, and Spanish overwhelmingly choose dubbing; despite its higher cost dubbing has been the accepted practice with these countries since the 1930s because their languages are so prevalent in the world market.

Subtitles are preferred in countries with a high percentage of imported films and a smaller population such as the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Greece, Slovenia, Croatia, and Portugal. In countries with more than one official language, like Belgium and Finland, films often have double subtitles.

English-speaking countries

English-speaking nations like the United States and the United Kingdom have fewer imported films. The U.S. tends to subtitle foreign films, and the U.K. imports most of its foreign films from the U.S. so there is no language barrier. The last decade has suggested that subtitled films can attain great acclaim and popularity in the U.S. and U.K. Since 2004, 23 subtitled films have made more than £1 million in Britain, according to the UK Film Council, compared to only 9 subtitled films in the 1990s.

In the 1990s, European cinema dominated in the U.S., but the "aughts" saw another continent gaining popularity. In the U.S., Asian films made up six of the top ten grossing imported films of the ‘00s, including the decade’s top grosser, Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. Lee’s film grossed $128 million, making it the highest-grossing film import by a $70 million margin, according to Peter Knegt of IndieWire.com.

Ten Top Grossing Foreign-Language Films of the 2000s

-

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon Taiwan, 2000, $128,078,872

-

Hero China, 2004, $53,710,019

-

Pan's Labyrinth Mexico, 2006, $37,634,615

-

Amelie France, 2001, $33,225,499

-

Jet Li's Fearless China, 2006, $24,633,730

-

Kung Fu Hustle China, 2005, $17,108,591

-

The Motorcycle Diaries Argentina, 2004, $16,781,387

-

Iron Monkey Hong Kong, 2001, $14,694,904

-

Monsoon Wedding India, 2002, $13,885,966

-

Y Tu Mama Tambien Mexico, 2002, $13,839,658

Source: Peter Knegt, “B.O. of the ‘00s: The Top Grossing Foreign-Language Films,” IndieWire, 20 Nov. 2009, Web, 30 Nov. 2009.

Subtitles

With the wide availability of foreign-language films on DVD and Netflix, and with more of them reaching American theatres, people are gradually becoming more accustomed to subtitles. There are still some entrenched in their views, but most viewers are overcoming their fears and accepting films from other nations.

Clever marketing also comes into play with the success of these subtitled films. The fact that several people in the audience did not know that Pan’s Labyrinth was in Spanish says a great deal about how films are presented in trailers and other forms of marketing. Hugo Grumbar of Icon Films explained that increasingly, “foreign-language films are sold as thrillers, romances or comedies rather than the latest French, German or Spanish hit.” For example, Michael Haneke's Caché changed its name to Hidden and had a trailer that hid the fact that it was French.

The title of del Toro’s fantasy, the Spanish El Laberinto del Fauno, was altered in translation as well: fearing that American audiences would confuse “faun” with “fawn,” the marketers went with the name “Pan,” even though the faun character is not meant to be the same creature from Greek myth.

Dubs

Dubbing films has another set of issues to consider, primarily domestication. Ultimately, the needs of the target culture are put before those of the source culture. Agnieszka Szarkowska argues that “all foreign elements [of the film] are assimilated into the dominant target culture, thus depriving the target audience of crucial characteristics of the source culture.”

Dubbing takes what is unfamiliar and “other” and neutralizes it, “re-expressing foreign cultural values in terms of what is familiar (and therefore unchallenging) to the dominant culture,” according to Basil Hatim and Ian Mason in their book The Translator as Communicator. The film loses its authenticity as a foreign film, if it is even marketed as a foreign film. Often, the dubbed, “de-cultured” film is presented to the viewer as a new product, not a transformed one, says Szarkowska.

So how do dubs change the film?

While the U.S. tends to subtitle foreign films, Disney’s release of Hayao Miyazaki’s animated films is an example of dubbing in the U.S. In 1997, Studio Ghibli, Miyazaki’s animation company, gave Disney the video rights to all its films that had no previous international distribution. Disney released the films in theatres dubbed with well-known American actors like Cloris Leachman, Patrick Stewart, Billy Bob Thornton, and Tina Fey (in DVD form the viewers have the choice between the sub and dub versions).

However, Miyazaki’s studio is well-known for forbidding Disney and other international distributors from making cuts or edits to the films. Miyazaki revealed in a rare interview that it was actually a producer and not he who mailed a samurai sword to the head of Disney when his film Princess Mononoke was being adapted for American audiences. Attached to the sword was a note that read, “No cuts.” Miyazaki himself supports the dubs and doubts that subs are much more authentic. In an interview with Xan Brooks, the director said, “When you watch the subtitled version you are probably missing just as many things. There is a layer and a nuance you're not going to get. Film crosses so many borders these days. Of course it is going to be distorted."

As a result, any edits that Disney makes to his film are so minor that only purists quibble over them. In Kiki’s Delivery Service, for instance, a woman offers the preteen protagonist a cup of coffee. With the Disney dub, the coffee becomes hot chocolate for fear of promoting coffee-consumption by children. While Japanese anime fans and film purists argue over the merits of dubbing and “Disneyfying” Miyazaki’s films, parents with small children (kids being a primary target audience) say that the dubs make it easier for the kids to understand and enjoy.

Another risk: Dialogue changes

Dialogue changes are another issue with dubbing films. Sometimes alterations to the text are unavoidable when the film is dubbed in another language. Roberto Benigni’s Italian film Life is Beautiful starts as a charming tale of a man wooing the woman he loves with his great sense of humor. Later he must use that same humor to shield his young son from the horrors of a Nazi concentration camp.

When the American soldiers in their tanks arrive to liberate the camp, one of the soldiers tries to reassure the Italian boy and says, “You have no idea what I'm saying, do you?” Young Giosué shakes his head. This exchange makes sense when the Italians speak Italian and the Americans speak English. When the film is dubbed entirely in English, however, the dialogue no longer fits. Instead, the soldier asks Giosué, “You’re not afraid, are you?”

With the dubbing, the viewer also has to suspend disbelief when Italians and Germans all regularly speak English in Nazi-occupied Europe. The viewer can choose to believe the characters are actually speaking in English or keep in mind that their voices were dubbed for English-speaking audiences. In either case, the magic and emotional impact of the original film is lost with the dubbed version.

Final Thoughts

If you're not sure which side I'm on, I'll go ahead and say that I generally prefer subs over dubs. I'd much rather hear the original language, with the actors' natural voices and emotional nuances, and read the original dialogue. Often with dubs I feel that some of the true spark of the film is missing.

I'm not alone in considering this question. The first decade of the twenty-first century saw a boom in the mainstream success of foreign films in English-speaking countries. The growing acceptance of subtitles means more audiences will experience foreign-language films in their original form. Cultures and languages may have their differences, and some messages risk being lost in translation, but the power of film transcends country boundaries and differing tongues. With time, perhaps those theatre-goers who originally balked at reading subtitles will learn to accept and appreciate what foreign cinema has to offer.

Sources

Box Office Mojo. Imdb.com, Inc., 2009. Web. 30 Nov. 2009.

Brooks, Xan. “A god among animators.” Guardian.co.uk. The Guardian, 14 Sept. 2005. Web. 30 Nov. 2009.

Erichsen, Gerald. “Mainstream Success of Del Toro Film May Bode Well for Spanish-Language Cinema.” About.com. About.com Guide, n.d. Web. 30 Nov. 2009.

Hatim, Basil and Ian Mason. The Translator as Communicator. London: Routledge, 1997. Print.

Hoyle, Ben. “Foreign films no longer lost in translation.” Times Online. Times Newspapers, 17 Aug. 2007. Web. 30 Nov. 2009.

Knegt, Peter. “B.O. of the ‘00s: The Top Grossing Foreign-Language Films.” IndieWire.com. IndieWire, 20 Nov. 2009. Web. 30 Nov. 2009.

Redwine, Ivana. “Pan's Labyrinth Two-Disc Platinum Series.” About.com. About.com Guide, n.d. Web. 30 Nov. 2009.

Szarkowska, Agnieszka. “The Power of Film Translation.” Translation Journal. Translation Journal, Apr. 2005. Web. 30 Nov. 2009.

Read more about foreign-language films

- A Guide to Foreign Films, Classic and New

The types of foreign-language films available to wide audiences have changed: foreign films can be popular thrillers, fantasies, and comedies. For years, Americans tended to associate foreign films with art... - Girls are the Heroes in Miyazaki's Films

Hayao Miyazaki, a cherished figure in Japan, is praised not only for his breathtaking animation style, but also for his gift of storytelling. His films heroes, usually children, learn the values of...