Understand Chords: Beyond Triads --Seventh Chords (Part Three of a Series)

Triads are still the most familiar chords—the ‘comfort food’ of harmonies. We looked at what triads are, and what varieties of triads exist, in Understand Chords, Part One. We then continued on in Understand Chords, Part Two to consider triad patterns in different keys.

But there’s a whole wide world of chords that are not triads at all. Some, like triads, are built upwards from a chordal “root” in thirds; others are structured quite differently. This article will describe seventh chords, which are most similar to triads—and most familiar to listeners, too.

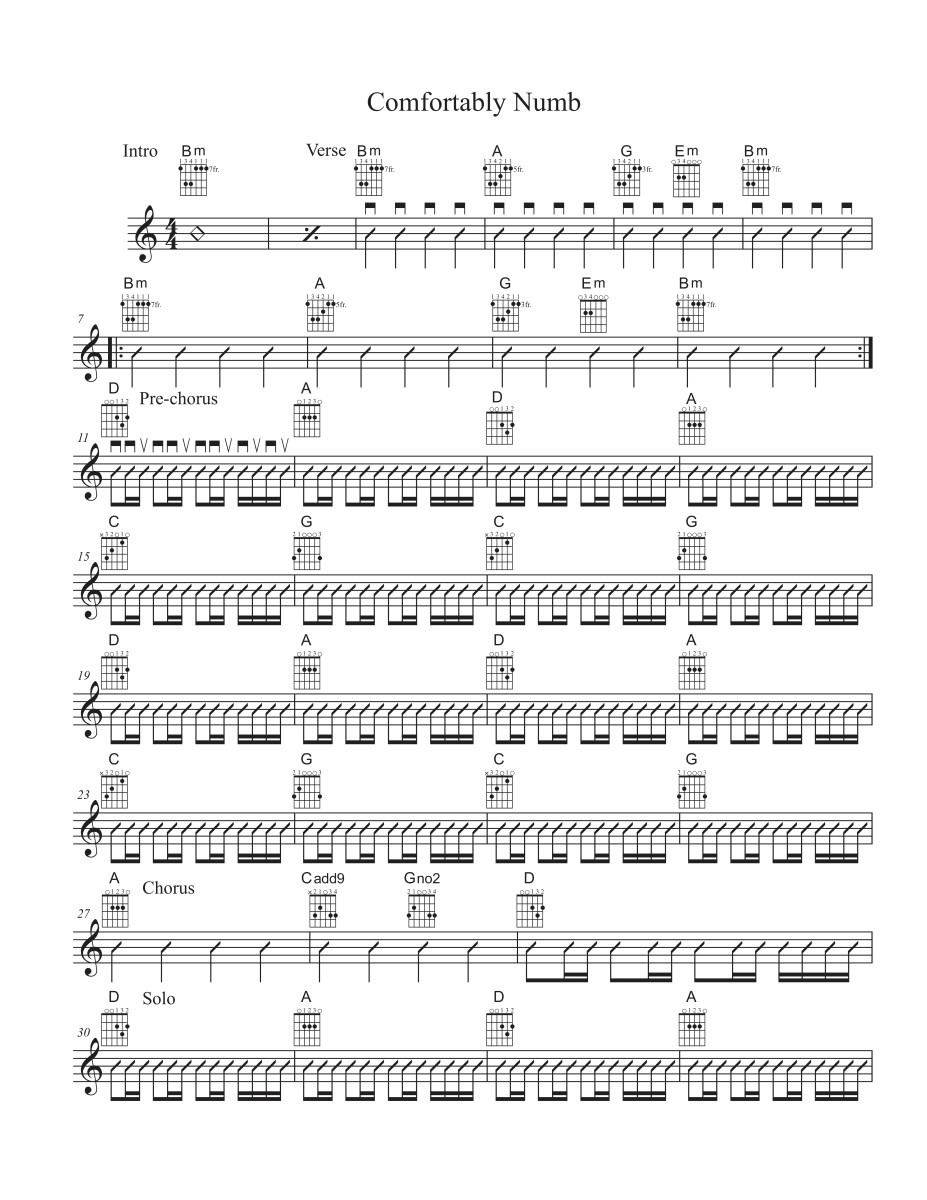

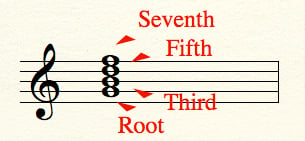

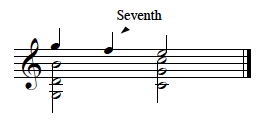

The concept of a seventh chord is simple. If you begin with a triad, which consists of a root, a third and a fifth, you can add yet another third. You would then have a four-note chord built in thirds, as shown below:

- Part-writing Seventh Chords: The Dominant Seventh Chord

The first of Doc's series on part-writing seventh chords: clear explanations and interactive exercises to help you master the essential skill of part-writing. If you're looking for greater depth on V7 chords, this might be your ticket.

The new chord tone—also called a “chord member”--is referred to as the “seventh” of the chord. (Logically enough!)

This particular seventh chord is pretty familiar, as we’ll illustrate in a moment. It’s actually the most common type of seventh chord, and has seen extensive use as an everyday harmony since before the days of Johann Sebastian Bach—and he died back in 1750! It is referred to by a couple of different names, more or less interchangeably if you aren’t too worried about theoretical niceties. One is “dominant seventh”—this refers to its position in the major scale. Another is “major-minor seventh,” which describes its intervallic structure, which can be thought of as a major triad with the addition of a minor seventh above the root. (A minor seventh is equivalent to a musical “distance” of ten frets or piano keys. In our example above, counting upwards from the root “G,” one key at a time, finds the tenth key to be the “F” shown as the seventh.)

Part of the usefulness of this chord in traditional practice came from a seemingly paradoxical fact about it: the dominant seventh chord is only found at one place within the major scale. It can only be built without using accidentals (that is, notes from outside the scale) upon the fifth scale degree—the so-called “dominant.” That might seem like a limitation at first blush, but it is actually useful because it means that the dominant seventh chord—unlike any triad—can by itself define for our ear the most likely key. When we hear a dominant seventh, we don’t need to hear another chord to know, as if by instinct, what the probable keynote (“tonic”) will be.

(Of course, art is not always about being predictable. Back in 1800, Beethoven famously began his First Symphony with the “wrong” dominant seventh, in a clever ‘fake-out’ that succeeded in getting scandalized musical amateurs talking.)

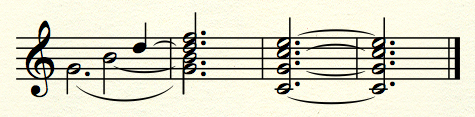

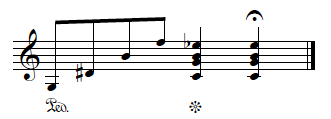

Today the major-minor seventh is often used more freely. In styles influenced by Blues this seventh can be freely substituted for any and all major triads. That means using accidentals, of course, and it means weakening the key somewhat. But it adds color and tension, and a certain ‘style.’ Here’s an example in which our (imaginary) house band tries out a chord progression, harmonizing it first with triads, and then with major-minor seventh chords instead.

Well, it's always fun to drop in on Vaclav and the lads. It's a fairly subtle difference between the seventh chords and the triads, especially with the other instruments distracting your ear; I'm sure many listeners will be hard-pressed to spot the difference.

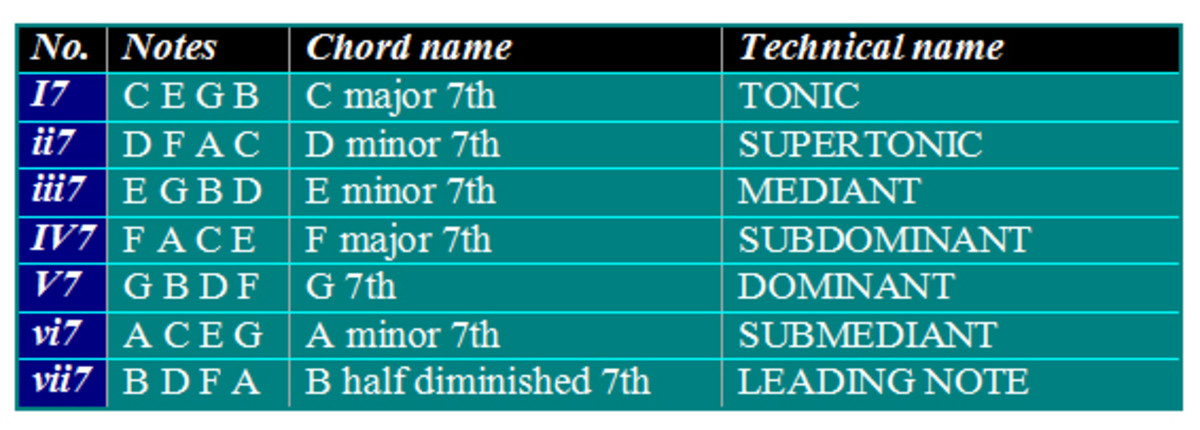

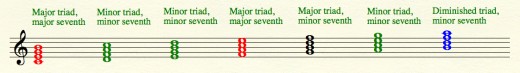

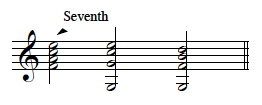

Staying within the confines of a major scale for the moment, though, what other seventh chords can be built?

As the example above shows, four distinct types of seventh chords are found within the major scale. In addition to the dominant 7th on scale degree 5, two other sevenths are built upon the major triads on scale degrees 1 and 4. In each case, the chord consists of a major triad topped with a major seventh, and is called a “major-major” seventh chord. Although this chord is not new—it can be found in Bach, albeit somewhat sparingly—it often sounds “jazzy” today, because it has been used much more extensively in Jazz than in Classical music. A very popular ballad using this sound very prominently is Chicago’s “Color My World” (1970); a sustained major-major seventh is the very first chord heard.

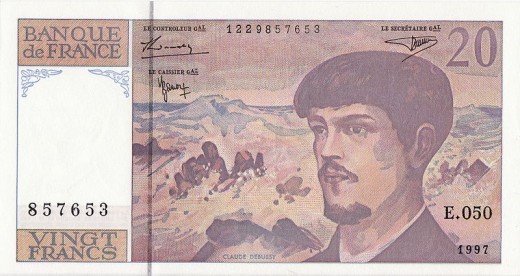

A more common seventh chord, though, is found built upon the 2nd, 3rd and 6th scale degrees. In each of these cases a minor triad is paired with a minor seventh to create a minor-minor seventh. It’s a versatile sound, basically adding a little tension to the plain triad. There are a couple of prominent examples using this chord prominently. Jorge

Ben Jor’s "Taj Mahal” (“recycled” by Rod Stewart in 1979 for “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy”) and Claude Debussy’s “Girl With The Flaxen Hair” both use it prominently. Here’s an idealized example similar to those two ideas:

There’s one more seventh chord in the major scale. The seventh scale degree has a diminished triad with a minor seventh above it. Using our now-familiar terminology, this would be a diminished-minor chord. This chord, too, has another name: the “half-diminished” chord. Here’s an invented example using it:

This nearly exhausts the seventh chords commonly used in Classical music; there’s just one more type, the diminished-diminished chord, more commonly known as the (fully) diminished seventh. It’s not found in the major scale, but can be constructed from the half-diminished chord by lowering the seventh by a half step, as shown below. This harmonic idiom became very important in nineteenth-century music. Here’s a cliché from the days of silent movies to illustrate the diminished seventh chord:

Silent movies, such as the popular serial The Perils of Pauline, were often accompanied with live music sound tracks. For large, successful theatres, these scores might be fully notated and might use an actual orchestra; at the other end of the spectrum, they might consist of a single pianist improvising appropriate music. The diminished seventh chord was a frequent ingredient, and often signified danger, stress or drama.

But the five common seventh chords--major-minor, major-major, minor-minor, diminished-minor and diminished-diminished--don’t account for all the possibilities that exist.

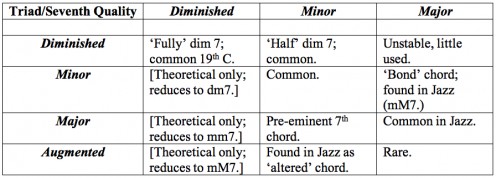

Here’s a complete chart. The headings at left refer to the quality of the triad, while those along the top describe the quality of the seventh. As shown, some seventh chords exist in a merely theoretical way because they are equivalent to simpler possibilities; these chords are marked with square brackets in the "comments" box and the equivalent is named.

This chart brings in the augmented triad for the first time. It doesn’t exist within the major scale, but can be constructed using the altered tones often applied within the harmonic and melodic forms of the minor scale, or by using other chromatic tones. It’s the most tense (“dissonant”) of the triads, as can be heard below:

Traditionally, it has been used quite sparingly. It is only seen with any frequency as part of a seventh chord when combined with the minor seventh. In this guise it’s used in jazz as a colorful variant of the dominant seventh. On rare occasions it may also pop up combined with the major seventh—though I haven’t so far found a specific example of this.

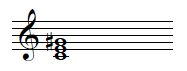

The diminished form of the seventh is worth a comment, too; as the chart shows, the only chord it can really be used for is the diminished seventh itself. The other theoretical possibilities are equivalent to more usual chords respelled in funky and pointless ways. For example, here’s the “major-diminished” chord and its normal equivalent:

That leaves only the minor-major seventh chord, which had a certain vogue in the Cool Jazz era of the late Fifties and early Sixties. This “cool” connection was perhaps the reason for its prominent usage in various James Bond movie soundtracks (and their knock-offs, as well, sometimes.) It’s quite tense; the upper three chord tones form an augmented triad.

If you’ve been keeping count, you know already that that makes nine different usable seventh chords, out of twelve possibilities. That’s still much more various than the four different qualities of triads—only two of which, major and minor, account for the great bulk of all harmonies used from about 1600-1900 CE. Greater exploitation of the sonic diversity of seventh chords is one of the reasons for the more complex harmonic color of music from the late 19th century and early 20th century. (It’s far from the only reason, though.)

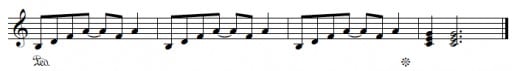

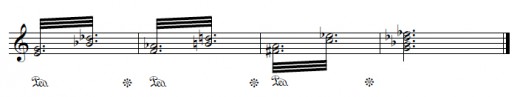

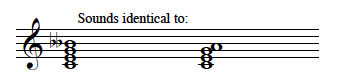

So far we’ve considered seventh chords purely from a harmonic point of view, building them up in the abstract by stacking thirds in different ways. But there’s good agreement among music theorists that that is not the way that seventh chords arose. Rather, they were the result of melodic lines interacting with triads in actual compositions. Only later did theorists arrive at the ‘stacked thirds’ concept. Here’s an example of how it worked:

Here the 7th occurs when the melody goes down from a “G” to an “E” over the “G” and “C” triads. The “F” connecting them sounds a major-minor seventh chord. Over time, this sound became more familiar and more accepted—that is, it became an independent chord.

Why does this matter? Because theory generally follows the ear, and not the other way around. The ear, accustomed to the descending line in this context, came to expect that the seventh of a seventh chord would descend stepwise. The theorist, observing this, noted that the seventh was “dissonant”—that is, unstable—and categorized the downward motion as a “resolution” of the dissonance. This became a norm for composers and further reinforced the expectation that already existed.

The result? A stylistic norm: if you are writing music in the Classical style you should (as your ‘default’ at least) resolve the sevenths in seventh chords downward by step whenever possible. (An acceptable alternate is to hold the seventh, if the following chord contains the seventh as a chord tone. See the example below.)

Since it’s a stylistic norm, it doesn’t apply to all types of music. For example, the ‘bluesy’ version in the band example above doesn’t resolve the 7ths; in this style the 7th chord is a fully independent entity and doesn’t need any “resolution.” The sound that results is different than the highly-refined texture of Classical music, but works perfectly well upon its own terms—part of which is the non-resolution of 7ths.

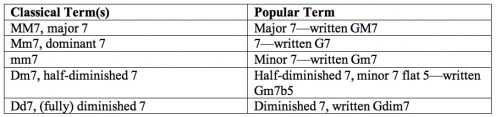

Speaking of various musical styles, there are different naming conventions for seventh chords--customs differ strongly between the Classical and popular realms in particular. Here's a chart to help you sort them out. Classical terms on the left, popular on the right—and the popular terms include a common way of writing each chord, shown for chords on “G.” Be aware, though, that there are alternate ways of writing them as well; an exhaustive list would be a whole other Hub!

So there’s your crash course in seventh chords. We’ve covered what they are, what they sound like, some prominent examples of their use, and how to resolve them (and why you sometimes should and sometimes shouldn’t.) There’s more you could say on most of these topics, but this should give you a good start on understanding these important sounds.

Next, we’ll go beyond the 7th chord—but let’s leave that little adventure for another time!- Sudoku Sherlock-Style: Getting To N-1

Get your sudoku game on with practical tactics! "At a bare-bones level, all Sudoku solving is about eliminating the impossible until just one alternative remainsas Holmes observed, the remaining possibility must represent the answer we seek..." - How (Not) To Practice Music Efficiently, Part Two

Practical tips on getting better faster. Don't make the practice mistakes I used to make! "So many ways not to practice music efficiently! In Part One we looked at a few of these ways..." - "Crystal Waters": A Meditation

Remember the Gulf spill? So do I, and so does songwriter Craig Reeder--and so do the folks getting sick today. "I might not finish this piece tonight. Its hot, really hot, and the wind is rising outside with the rising storm.... - Global Warming Science, Press, And Storms: Nils Ekholm

Nils Ekholm is little-remembered outside Sweden, but lived a fascinating life whose impact is still felt. "Scientists are expected to live and die on the quality and integrity of their data analysisbut usually that is a metaphor..." - Inuk Was A-Positive: A Brief Meditation

Thoughts--and feelings!--on an unexpected science fact. "Inuk was A-positive. For some reason, that information hit me with a certain imaginitive force..."