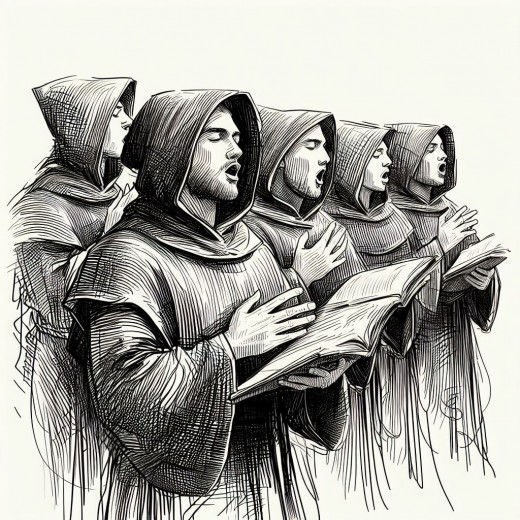

Gregorian Chant

The Gregorian Chant is the liturgical music of the Roman rite of the Catholic Church, composed in the early Middle Ages. Although some manuscripts from the 9th century open with a poem attributing the music to Pope Gregory (presumably Pope Gregory I, reigned 590-604), the term "Gregorian chant" was not used to identify this music until the 17th century. The medieval terms were cantilena romana and cantus planus (whence the term "plainsong" in English). Few scholars today hold that Pope Gregory I wrote any of the music, although he is still credited with liturgical and textual codifications that affected the church music of his time and with the establishment of a school for cantors (schola cantorum) that undoubtedly was the stimulus for a new flowering of church music.

History

The claim that the melodies now known as Gregorian chants originated in the 4th and 5th centuries from early Jewish and Middle Eastern models and were then codified by Pope Gregory around the year 600 is an oversimplified view. Also, few scholars see any relationship between classical Greek music and Gregorian chant. The many similarities of melodic structure show clearly that Gregorian chants did have a relationship of origin to aspects of other Middle East cultures (Jewish, Syriac, and Byzantine) but exact parentages are not traceable because of the lack of written musical documents of Gregorian chant before the 9th century. The other chants, moreover, survive almost entirely in oral traditions.

Before the 9th century, various musical traditions existed on the European continent: a Milanese tradition, a Galilean tradition in France, and a Mozarabic tradition in Spain. The first documents recording Gregorian chants come from the 9th century, the result of attempts by Charlemagne to obtain liturgical and musical unity within the Holy Roman Empire. This music, it would seem, was a composite of Roman and Gallican traditions that fused at that time in the Frankish empire. The Milanese tradition continued to exist but was influenced by its Gregorian neighbor; however, the Mozarabic was suppressed in 1059.

Since the first written melodies are from the second half of the 9th century, their age cannot be ascertained with certainty. An oral tradition preceded this written tradition, but it must have resembled the written tradition, with many local variations. It is noteworthy that in the late 9th century there arose various schools of music writing that were quite different in detail but built around a similar mnemonic device of accents to indicate relationship of pitches. It can thus be seen that a widely diffused similar oral tradition preceded these first written attempts.

Repertoire

The first complete manuscripts of Gregorian chant fell into two categories: those that arranged the pieces by their liturgical use for the Mass or for the Office (antiphoners), and those that arranged chants (antiphons and other chants) according to their tonal modality and liturgical sequence (tonalia). The second type of book was a necessary didactic device because of the large number of pieces the monastic choirs had to learn. The book of Mass chants was called the Antiphonarium Missarum (later the Graduate). Supplementary chants sung by soloists at Mass were often written in separate books called cantatoria, processionalia, or tro-paria. (Today most of the Mass chants and the Office chants for principal feasts have been gathered into one book, the Liber Usualis.) It can be stated with assurance that the monastic choir after the 9th century would have sung a repertoire of about 3,000 pieces in a year.

The two largest categories of pieces are antiphons and responsories. The historical origins and evolutions of these categories are vague, but by the 9th century they had assumed distinctive characteristics. Antiphons were pieces sung before and after the singing of Psalms, the Psalm itself being sung according to fixed musical formulas that permitted the singers to divide into two groups and thus alternate verses. Responsories were more elaborate pieces of music assigned to soloists, in which the choir took part by singing a form of refrain. To these larger categories must be added the older hymns and newer forms of medieval poetry (sequences and tropes) necessary for the medieval liturgy, which was becoming more elaborate and solemn.

Musical Characteristics

Since the texts set to music were predominantly prose (most especially from the Psalter), the music had to develop a freedom that permitted its adaptation to texts of various irregular lengths and structures but respected the inner musical laws of balance and form. Like other Middle Eastern chants, Gregorian chant probably originated from a repertory of musical formulas freely adapted to texts of varying length and complexity. The more rigorous of these formulas were those used for the

Psalms

Here the music reflected the structure of the Hebrew poetry with its irregular verses, composed of a statement and its response. These formulas were cataloged into eight categories that medieval theorists later identified with the classical Greek modes. How much the theory of Greek music taught in the Carolingian schools and inherited from Boethius affected the practice of music that the cantors had inherited can never be known. The 9th century made zealous attempts to bring these components together, a process that was successfully accomplished by Guido d'Arezzo around the year 1000. It became customary to assign each piece to one of eight modes according to range, ending, and predominant notes.

In describing Gregorian musical style, scholars first have distinguished two extremes: pieces that are set with a single note for each syllable (syllabic chant) and those that consist of long vocalises (melismatic chant). Between these extremes lie the largest number of pieces (sometimes called neumatic or semisyllabic), where several notes are given to each syllable, but with great elasticity and variety. Since the chant is purely vocal, unaccompanied music, its entire form comes from the structure of the melodic line and the text. Very little use is made of musical repetitions and sequences, but immense diversity is obtained even within similar patterns and formulas. The melismatic chants, sung by soloists, often required prodigious vocal ability and range.

Chant Rhythm

The subject most debated among scholars is the precise nature of Gregorian chant rhythm. It is generally accepted today that it was not metrical in the same sense as later polyphonic music or romantic music. On the other hand, all admit the principle of longer and shorter notes that fluctuated around a basic pulse. The revival of interest in Gregorian chant by the monks of Solesmes in the 18th century led to their devising ways of trying to put these imponderables into a system they could use, but its historical basis is still much controverted. Solesmes scholarship, however, has made available the manuscripts needed to study Gregorian chants as they were first written down, before they became influenced by the rise of polyphony and subsequent aesthetic concepts.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2010 Bits-n-Pieces