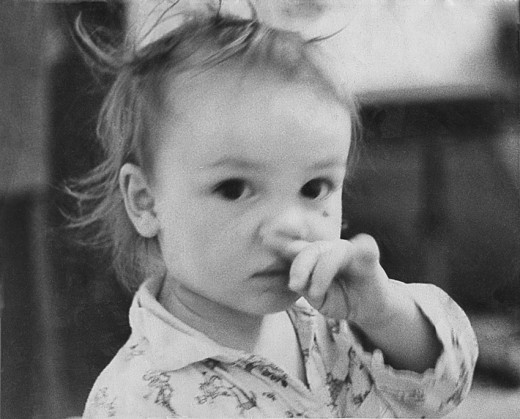

Joseph Stone 15/09/1980

Joseph was born sometime in the early hours of the morning, September 15th 1980. It was one-thirty in the morning. Or at least I think it was. I have a clear visual recollection of the clock on the delivery room wall - one of those standard, circular hospital clocks with clean black figures and hands - and it reads just after one-thirty. I can even see the slim, red second-hand ticking round. It's just that I can't be sure whether it's a real clock or not. I may have made it up.

That's the trouble with memories. You never really know where they're coming from.

I have other memories too. I can see the flushed effort on his mother's face as she forces down and down to the cheer-leader chants of the nursing staff. "That's it dear: push, push." I remember thinking that it looked like mighty hard work, that's why they call it labour. And one funny incident. One of the nurses handed me a glass of water. "Thanks," I said, taking a sip and setting it down on the side. The nurse gave me a curt, disbelieving look. It was only later that I realised that the water was meant for the woman on the bed, not for me.

Later I remember the surrealistic image of his head pooping out from between her legs, poised in a moment of Monty Python silliness, before the rest of his body slithered out like a blood-flecked snake from its red lair. And I remember the look on his face too, like one of those Buddhist demons, all crimson fury, as if he was fuming with indignation that we had dared exorcise him to this place, when he was perfectly happy where he was.

Mostly I remember the moment when he was laid upon his mother's breast, and how she glanced from him to me. There was something indescribable in her eyes, like some glint from another star; something warm but wise, elemental but kind, strange but friendly. All-embracing. Call it love. There is no other word.

There were only three people in the world in that moment. No one else mattered.

- Fierce Writing

Not so much Rage Against the Machine as Slightly Peeved the Taps Won't Work - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/C._J._Stone

Scunthorpe

And then, when it was all over, and his mum was taking a well-earned rest, I was cast into the neon emptiness of a Scunthorpe night, and I felt strangely bereft, strangely choked. Why Scunthorpe of all places? Because that's where we lived at the time. Or rather, we lived in Barton-on-Humber, about 15 miles away in what was then South Humberside. So Joe has "Scunthorpe" as his place of birth, both on his birth certificate and on his passport. Poor Joe. Of all the legacies of an itinerant life, this one must be the most peculiar for him, the most difficult to comprehend. Because that's all it is to him, a mystical place-name on his birth-certificate. He's only ever been there once.

I rang up my parents from a telephone box and told them the news. They congratulated me. It didn't help. I felt very alone. Later I slept on a wooden bench in Scunthorpe bus station, and awoke in the grey dawn to the sight of oil-stained concrete and scattered crisp-packets.

Well I may have got the details wrong here. I may be romanticising. But one thing I am sure of. One thing I know for certain. I know how it felt for me. It was as if, in being born, Joseph had changed the world forever. I remember thinking exactly that: that this one, small, bright new life had breathed new light into the world; a new perception, a new thought. It was a spiritual thing. He was like Jesus to me. I was absolutely certain about this, that the whole world had changed because of the birth of this one child.

Which it had, of course. But only for me and his mum.

After that they came home, and there were several weeks - months maybe - in which I had a pang in my chest like a hot dagger. It was difficult to know what this meant. It was a very corporeal kind of a feeling. Not mystical or emotional. Of the body. Maybe the body is the soul in another form. Maybe what hurts is what is real. But a baby is a very demanding creature. All tongue and arse and lungs. An innocent dictator, he stands over everything, a little Hitler making raucous, unintelligible speeches about the Motherland. Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Fuhrer. Gimme, gimme, gimme. I want, I want, I want. Sometimes it became very hard to bear. Sometimes, I'm afraid, I even resented him.

WOULDN'T YOU AGREE, BABY YOU AND ME,

WE'VE GOT A GROOVY KIND OF LOVE?"

— Wayne Fontana and the Mindbenders

Groovy Kind of Love

But there were compensations too. There were the Arabesque swirls of a black, wrought-iron candle-stick holder hanging on a hook on the back of the bedroom door, and Joe's reaction: how he would look at it and point and laugh, as if this was the best joke in the world, as if this mundane object held some immense secret and he was trying to impart it to us. And the song I used to sing, rawly and croakingly, into his ear, as he lay with his head on my shoulder, as I danced about trying to get him to sleep:

"When I'm feeling blue, all I have to do

Is take a look at you, then I'm not so blue

When you're close to me, I can feel your heart beat

I can hear you breathing near my ear

Wouldn't you agree, baby you and me got a groovy kind of love."

It was a song I'd loved as a child.

We moved around a lot in Joe's early years. From Barton-on-Humber to Bristol. From there to Whitstable in Kent. From estuary to estuary, for some reason. It's because I'm a Brummie. Brummies always have a fascination for the sea.

And, despite the moves, life developed a routine. It was one of those things. Always, "who's going to look after Joe today? It's your turn to get him up." "No, it's your turn." And in the following years his mum and I drifted apart. We no longer knew whether we were together because of each other, or only because of him. I became sullen and depressed. She was much younger than me. She'd had Joe at a very early age. Maybe she longed to have her own young life back. Eventually we split up.

This is a very ordinary kind of a story, of course, and I'm sorry if you've heard it before. It is the story of the late-twentieth century. Where it is maybe a little different in our case is in the situation we found ourselves in when we split. We were living in a commune. I'd had enough residual hippiedom in me to have been able to engineer this situation. So, while his mum continued her college course in London, Joe stayed with me. And - being sullen hippies, all of us - child rearing was a shared occupation. Later, again, I moved out of the commune, but the shared child-care continued. So that was how Joe was brought up, shuffling between a shared house in one part of Whitstable, my council-owned maisonette in another, and his mum's flat in London.

It's a surprise he isn't completely mad. He told me he's been counting the times he's moved. Thirteen times, he reckons, in only a few more years.

Where we can thank that commune is that Joe never felt the split like a schism in himself. He never felt like he was forced to choose between the two adults. Because there were many more adults in his life. I was only one of them. His mum was only another. So: no problem really. He could navigate his way between the emotional reefs with a certain grace. He had other people to refer to.

Which kind of brings us up to date. Joe is 18 years old now, and he lives with me. We share a rented house in Whitstable. He's just passed his driving test, and is currently doing his A-levels. The other people in the commune have moved away, though he keeps in contact with them. His mum still lives in London, where she pursues a successful photography career. She's married, to another photographer. We all seem to get along.

And Joe is a typical young man. Smart-casual, with a citrus-gel quiff, and a habit of wearing aftershave though he hardly needs to shave. He drives his car - a Citroen AX - with a kind of controlled insouciance, changing up the gears and accelerating at an alarming rate. He's not at all like me. He's not at all like his mum. He's not at all like the other people in the commune, though he's learnt a lot from all of us. In my case, what I've had to teach him has been mainly negative. How not to live your life. How not to mess up your relationships. He's learnt his lessons well, being self-possessed and extraordinarily loyal. It's like he has learned the courage to be ordinary.

A credit to his Old Man.

© 2009 Christopher James Stone