Thomas Alexander - A Black History Month tribute

My father's journey through America's changing times

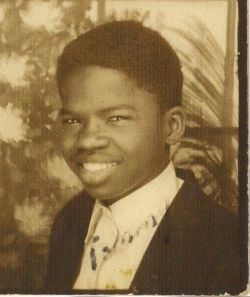

My father, Thomas Morris Alexander, is such an exceptional man. A talented engineer, an inspiring poet, a beloved pastor, and a devoted husband, father, and grandfather.

I wanted to share with you some of his life story, with an emphasis on the parts that relate to the African-American experience. This is my contribution for Black History Month.

I love you, Daddy!

When I told Dad that I was going to make a web page about him as an inspiring African-American, he said, "When you say 'inspiring', I guess you mean breathing, so I suppose I qualify!"

Before my dad was born - The migration to St. Louis

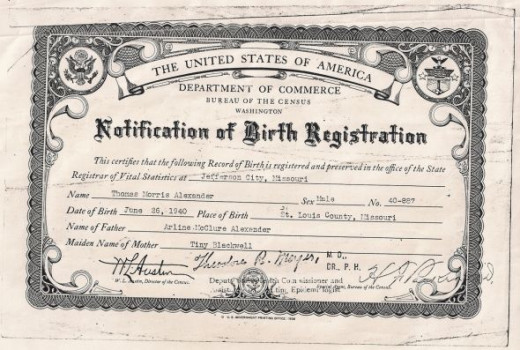

My father's parents, Arling and Tiny Alexander, had both grown up in Ripley, Mississippi. After their marriage, they moved to St. Louis, Missouri. The area where they lived was called Kinloch. Kinloch is the oldest black community in the state of Missouri.

Arling and Tiny had 16 children. My father was their eleventh child.

The family that Thomas Alexander was born into

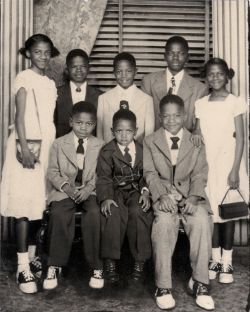

This is a photo of my grandparents with their children. About 1945.

Using facial clues and logic, I'm going to try to identify everyone in this picture. Then I'll have my dad look at it and tell me if I was right. Here goes:

Top row, left to right: Ruth, Simeon, Edna, Pruett, Emma, Carl, Ernest.

Bottom row, left to right: James, Tommy (my dad), Arling, Granddad (Arling McClure Alexander, Sr.), Mary, Granny (Tiny Blackwell Alexander), Freddy, Frankie, Irma, Sara.

Woohoo!! Dad said I got them all right!

Don't try to find Bishop Henry Alexander in this photo; he hadn't been born yet.

Life in St. Louis

(In this Easter Sunday photo of the younger half of the Alexander children, Dad is standing in the back row, second from the left.)

Tommy Alexander was the 11th of the 16 children. He was one of the quieter children. He loved literature and poetry. The fact that he stuttered also led him to be less vocal than some of his brothers and sisters.

The Alexander family was poor. Dad isn't sure whether the other families in their community tended more toward middle class or toward poverty, but either way the Alexanders were poorer than anybody else. But despite their poverty, there was a strong emphasis on education in their household. They were not a family where the older children would drop out of school to get jobs. They had jobs AND went to school. At various times, Dad worked at a grocery store, a tuxedo shop, and shining shoes at the St. Louis airport. (He once shined Yul Brynner's shoes, and he once shined Jerry Lee Lewis's shoes.)

I've heard my aunts and uncles talk about frequently going to school hungry. Dad remembers once when he was 6 or 7 years old, he was walking to school and saw a doughnut laying on the ground in the rain. He picked it up and was about to eat it until his siblings reproved him and told him not to.

Once in Junior High School some of the other students were teasing him about his shabby clothes. His teacher told the teasing students that Tommy had a high IQ and was likely to "be something" someday.

Besides being dirt poor, the other thing that made the Alexanders "different" was their devout and strict religious faith. Their parents had converted from being Baptist to the Oneness Pentecostal (Apostolic) faith in the early years of their marriage, and their household revolved around church activities. Dad is proud to have grown up under the leadership of distinguished pastors in the Pentecostal Assemblies of the World, including Bishop Morris Golder and Bishop James Johnson.

Back in those days, PAW churches followed very strict codes of behavior. Along with eschewing alcohol and tobacco, they also had very high standards about modesty in dress (ladies didn't wear makeup, jewelry, slacks, or open-toed shoes) and shunned many forms of "worldly" entertainment. When Dad was in 3rd grade, his class was doing a square-dancing activity. His teacher noticed his very half-hearted participation and actually thought he might be ill. When she took him aside to ask him what was wrong, he told her that they didn't believe in dancing. She asked him more questions and he explained further about all the things they didn't do.

But they considered their lives to be very full and had high expectations of themselves. Dad loved to read stories about people who accomplished great things. When he would finish reading a good biography or other story, he would feel so inspired to accomplish something of his own that he would clean his room. This made him feel that he was making the world a better place in the only place where had any influence so far.

Schooling - Segregated schools

The song "National Brotherhood Week" by Tom Lehrer

From kindergarten through the end of 9th grade, Dad went to segregated schools in St. Louis. He never had any sense of the schools or teachers being lacking in any way, but he's not sure about the bigger picture as far as how they compared to the white schools.

Dad remembers the pep talk that his teachers used to give him and his classmates when Brotherhood Week was approaching. Brotherhood Week was the one time in the year when the black children in St. Louis were allowed to go to the movie theater. "Now children, I know that when you go to the movies you're going to be on your very best behavior to show everyone just how good you can be." This talk was wasted on the Alexanders, of course. They wouldn't set foot in a den of iniquity like a movie theater.

Integrated schools

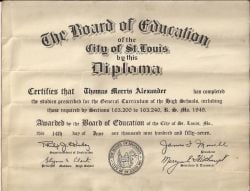

In the 10th grade, Dad transferred to Soldan High School. That year, 1955, was Soldan's very first year of integration.

As Dad recalls it, integration seemed to be a pretty smooth transition for the students. They got along pretty well. But it was more difficult for the school faculty to adjust to the changes. Especially uncomfortable for them was seeing black boys and white girls talking together.

A cute example of the changes brought by integration was the school's talent show that year. The talent show had been an annual tradition at Soldan for many years, but integration brought a new style of performances that the school staff wasn't sure how to respond to.

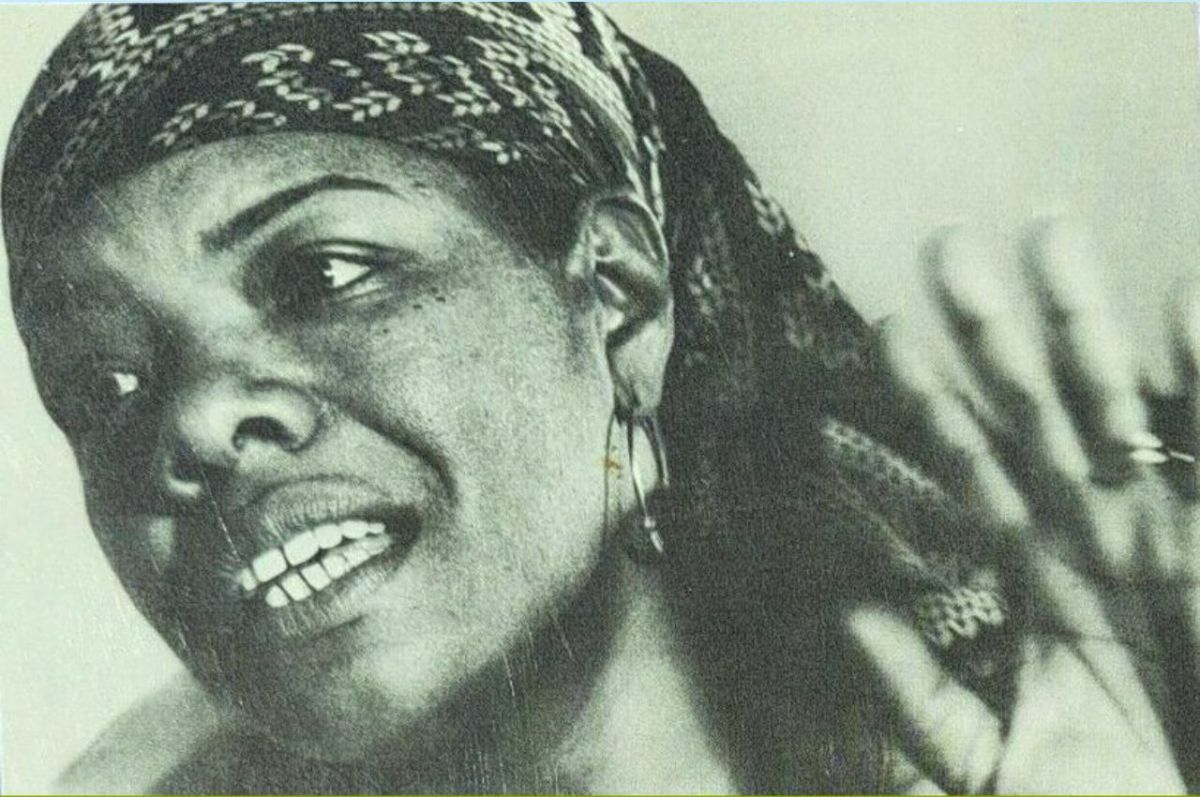

Guess what? My dad went to high school with a celebrity! Recording artist Fontella Bass grew up in St. Louis and she was also a part of that first integrated student body at Soldan. She definitely made her mark on the talent show. Some other black students had done performances that brought a bit of a "soul" sound, but the powers-that-be were really not ready for what Fontella was cookin'. It definitely resulted in some ruffled feathers.

This is the song that Fontella Bass sang during the talent show at Soldan High School. Of course, she didn't have a band behind her. Instead, she accompanied herself on the piano.

If Fontella's dream was to be that girl at center stage in front of the band, her dream came true.

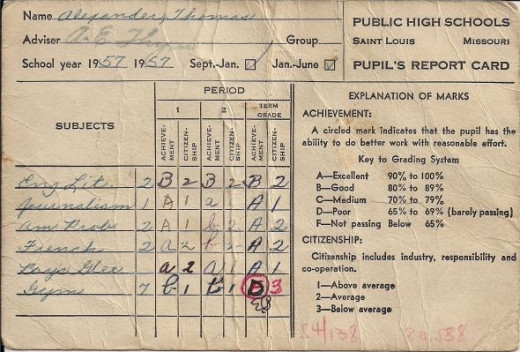

Dad's legendary 12th grade report card.

One B, four As, and one F. The F was in Gym. While other students were writing papers and cramming for exams in the final weeks of school, Dad was running laps trying to bring his F up to a D.

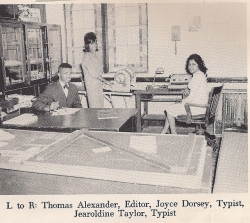

Dad doesn't remember getting especially good grades in high school, but his report card clearly shows otherwise. At Soldan, Tommy showed a strong interest in English and journalism. He was on the staff of the school newspaper, contributing stories and original poems.

Dad's personal civil rights movement

There were a few incident's in my father's life where he took it on himself to act out against injustice in his own small way.

The "shopping while black" encounter

When Dad was about 15 years old, he had an experience at a department store where a saleslady decided that he looked like a potential thief to her and followed him like a hawk all over the store. This is a common complaint from black people, especially young men.

Tommy, the English major, fought back the best way he knew how. He wrote a poem. After he left the store, he sat down and wrote it out, then walked back in and presented it to the lady. I don't know how much impact his action had on the overall plight of blacks in America, but I suppose that the next time that particular woman saw a black boy in her store, she knew that he might be a thief OR he might be a poet.

Here's Dad's original poem. Note the very Burns-ian title. The ending of the poem is rather intense, but remember that he was only 15:

To a Clerk in F. W. Woolworth (who doesn't trust me) by Thomas Alexander

I was moved with great concern

As I saw you twist and turn

When I came into your store an hour ago

I conceived a million ills

Twisted back, hospital bills

And aye, that too crooked your spine might grow

At my every move you lunged

As we talked about the sponge

Not a move I made escaped your watchful eye

You couldn't satisfy my needs

For contemplating my misdeeds

I was so embarrassed I thought I should die

I've seen others who were wary

As they scrutinized their quarry

But your brazenness was really new to see

And your "whisper" brought a shock

You could hear it for a block

As you told the cashier your distrust of me

Here's a word of good advice

'Cause I think you're kind of nice

Although your actions this thought belie

If you get a periscope

Then I think that there is hope

To maintain your health and still remain a spy

To make deceit your master

Will result in sure disaster

Unlike Nathan Hale of old I think I'd say

That it's better far to live

Than long for more lives to give

Death, of course, is the price that all spies must pay.

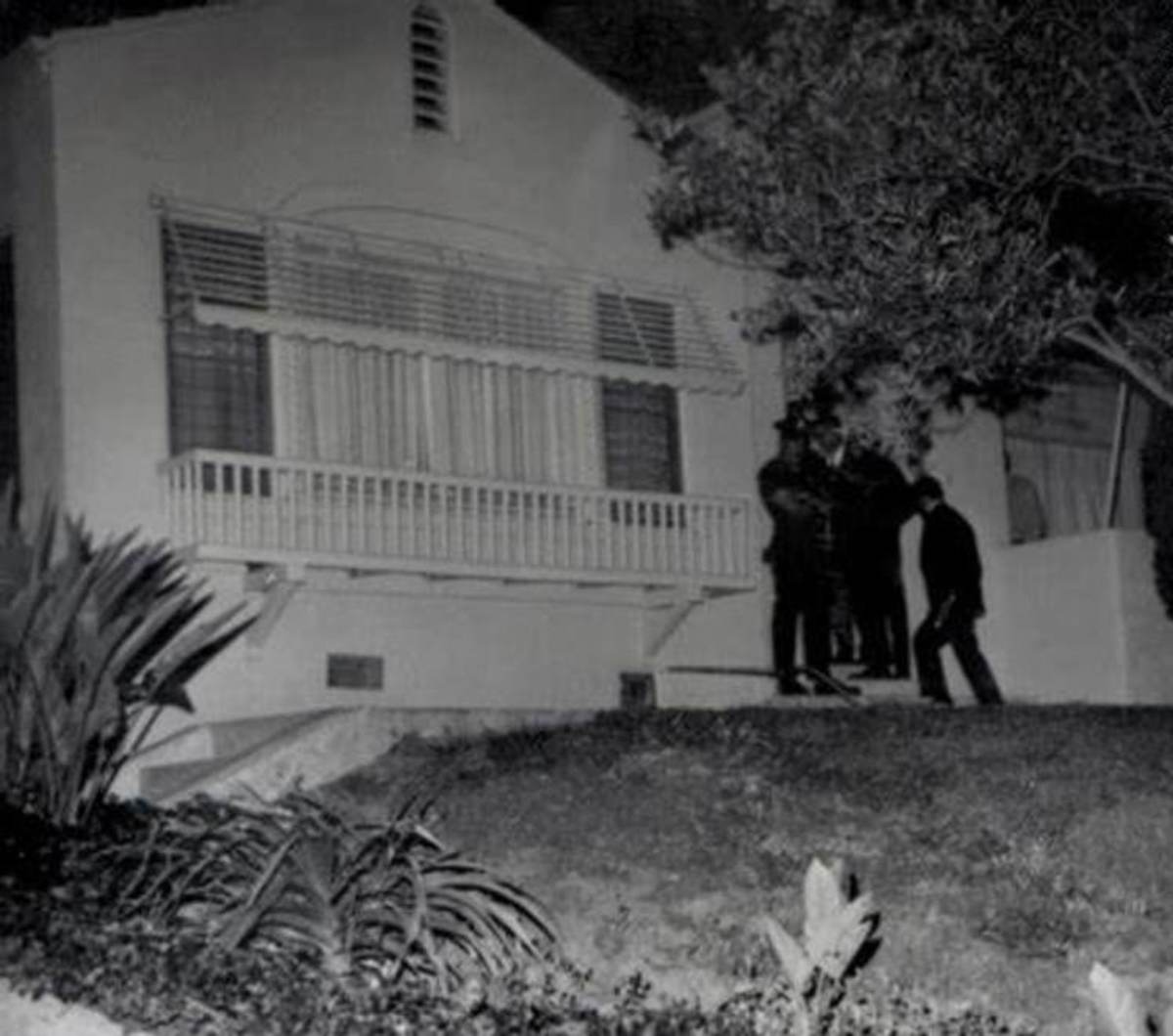

The sit-in at the diner

Yes, Dad staged his own sit-in long before it became cool to do so. Here's a description in his own words:

I must have been in my teens. Circumstances that day required me to go out on my own to get my eyeglasses replaced. This meant a trip on the buses to a different part of town. It also meant ending up someplace other than my own regular neighborhood at lunchtime.

I loved chili, and I soon found a place where it was offered. These days I would call the place a "greasy spoon", but back then it was grub and I was hungry.

It was lunch time and the place was jammed. I ordered my cheeseburger and chili. I had frequently, in the company of my older brothers, ordered food in similar situations, always adding the familiar phrase "to go." But that really wasn't necessary. This was a white institution, so it went without saying that my order was "to go." Maybe it didn't catch their attention that I didn't specifically say the words "to go," and they certainly couldn't see in my mind that on that day, for some reason, I had no intention of taking my food and going out into the cold, to walk down the street and find a place to stand around and eat.

So when my food was brought to me in a nice brown bag, and after it was paid for, I simply sat down at the counter, opened the bag, and began to eat. It was in the mid-1950s, long before lunch counter sit-ins became fashionable, but this was a sit-in borne of necessity.

The distressed expression on the face of the white waitress told me this wasn't going to go smoothly. After repeatedly informing me that I couldn't eat there, and her remonstrations falling on deaf ears, she resorted to more desperate measures. Her final actions were to snatch the sandwich from my hands, ring up a "no sale" on the cash register, and call in a nearby policeman to complain that I hadn't paid. The policeman certainly knew what was going on, and had no desire to have a more unpleasant ending than was necessary. He finally took me aside, and (although I don't remember his exact words) he let me know there was no need to make trouble about this. Essentially if I would go away quietly, he had no desire to take further actions.

So, I was back out in the cold and on to the streetcar, a little bit hungry, and a little bit disillusioned. But that was life in St. Louis in the mid-'50s.

Growing up and moving on

Choosing a major

Tommy knew what he wanted to do with his life. He wanted to be an author. But he had to be "practical", don't you know. Helpful white adults around him told him to abandon his dreams. His boss at the market (where he worked 20 hours a week while in high school) told him that if there were any successful black authors, he had certainly never heard of them. Don't even try it.

And journalism? Advisors at his school told him that there would NEVER be a demand for black journalists. Drop that idea, too.

So that was that. He couldn't be an author or a journalist because he was black.

What happened to the fight down inside him that made him stand up to the store clerk and the lunch counter lady? Here's my theory. I think that after growing up in such poverty, Dad wanted a stable career more than he wanted to fight for his dream profession.

His next thought was that he should probably go ahead and be a schoolteacher like all of his sisters were doing. The only problem with that was that everyone who wanted to study teaching had to pass a speech test, which would have been an insurmountable obstacle to the boy who stuttered.

What else could he do?

Medicine? Too many years of school.

Law? Too many dishonest people in the field.

Engineering? Why not!

Attending college

He enrolled in Harris Junior College in the Pre-Engineering program.

The busy-ness of life in his large family and his lack of preparation for being a science major made things difficult for him. He dropped out once during his first semester, but went back and completed it. Again in the second semester he dropped out, this time for an entire year. He got a job at the Post Office, sorting mail.

But Dad knew that he didn't want to be stuck in those kind of jobs forever. So after a year, he quit his job and returned to Harris. His father couldn't understand it. To Granddad, the Post Office was one of the most stable jobs a person could hope for. And Tommy was quitting to go to college??

Dad's perseverance paid off. His skills in engineering developed and grew. He received an Associate Degree in Pre-Engineering in 1961.

The next step should have been attending Missouri School of Minds at Rolla (the only engineering school in Missouri). But he didn't have the money and couldn't find work. The Post Office wasn't hiring any more and he didn't know what to do.

Someone said that out in Los Angeles the streets were paved with jobs. There was all manner of work to be had. So Dad left St. Louis and headed out to Los Angeles in 1961. Most of the Alexander family followed the same path over the course of several years, and now most of us live in Southern California.

The journey west

Dad was 20 years old when he left St. Louis for Los Angeles in search of employment, armed with his Associate Degree in Pre-Engineering.

Finding his way in LA - Finding a job

Tommy arrived in Los Angeles in May of 1961. In June, he turned 21 years old. That summer was spent looking for work, especially at government agencies. He didn't find anything right away, even though he wasn't being picky (some of the warehouse jobs he tried to apply for turned him down, say that he was overqualified). By September he was wondering whether he should go back home.

But in October of '61, things turned around. He got a job as clerk at the LA County Department of Public Social Services, making a decent $288 per month. The typical rent for an apartment at the time was about $100/month, but Dad didn't get an apartment yet. He stayed with his older sister, Ruth, and her husband, Jake Ross, in a house on Lima Street in South Central LA.

In January of 1962, Tommy finally got work that was in his field, an entry-level engineering position at CalTrans. But he was only with CalTrans for 3 weeks, because on February 4th 1962, he began work for the agency that would employ him for the rest of his working life. He went to the Los Angeles County Flood Control District as a Junior Engineering Aid, making $417/month. Now THAT was some good money!

Finding a church

Tommy didn't lose his spiritual bearings when he moved to the big city. He got involved in church right away. Back then there were two major Pentecostal Assemblies of the World churches in Los Angeles -- the Apostolic Faith Home Assembly and Bethany Apostolic Church. Dad visited both of them and ended up joining Bethany, which was being pastored by Evangelist Bell, the widow of the previous pastor. Mother Bell was leading the church temporarily while they awaited the arrival of the Eld. Robert McMurray was coming from Ohio to be the new pastor. Eld. McMurray arrived in 1962, and my dad was there on the front row of the church when he arrived.

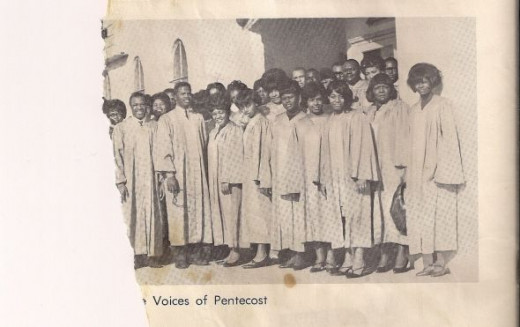

Dad started singing in the choir at Bethany and eventually became the director of the choir, starting in about the spring of 1963. The song he brought to the choir that made the most impact in the history of Bethany was "Trust Him" by James Cleveland. When Dad first taught the song to the choir, he had his brother, Arling Alexander, Jr., singing the lead part. Eld. McMurray loved the song and adopted it as his theme song. It was sung every Sunday at Bethany, with Eld McMurray doing the lead himself, right before the sermon. Long after my parents had left to minister in other churches, "Trust Him" remained Bishop McMurray's theme song until his death in 1994.

Bishop McMurray and the choir at Bethany singing "Trust Him"

Finding a mate

According to my father's account, he had some trouble connecting with the girls at Bethany. He was smart and had a good job, but he also stuttered, wore glasses, and didn't have a car yet, which didn't exactly make him Mr. Popularity.

But to tell the truth, he had some reservations about the women in Los Angeles as well. Compared to the young ladies he had known at his old church in St. Louis, these Bethany girls seemed kinda -- worldly. The dress code standards at Bethany were certainly not the same as the ones he had known back home.

His friend, Cortez Madkin, started talking about San Bernardino as a good place to meet girls. Dad's mother, Granny Alexander, visited San Bernardino and highly approved of the skirt lengths of the young ladies she saw out there. So in February Dad started trekking out to San Bernardino, visiting churches and looking for potential girlfriends (by then he had a car).

One of the eligible young ladies in San Bernardino was Marian James, the youngest daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Richard James. They actually first met in Los Angeles, at a concert that Mom and some friends had come down to attend (Mom and Dad can't remember for sure now exactly who it was that introduced them). That chatted a little after the concert, and he discerned that Marian had "class". But it was after Dad started visiting San Bernardino that they really got acquainted.

A Sunday School class that Dad visited at Pastor Vessup's church was the place where Marian got her first strong impression about Tommy. There was a question put out to the whole class, and his answer displayed an intelligence that she had rarely seen in a guy. She was bowled over!

Eventually, he ended up asking her out to a restaurant. On their first date they talked about philosophical ideas and Shakespeare and all kinds of things that Mom had never been able to discuss with a date before. Very quickly those trips to San Bernardino were no longer about meeting girls, but rather about seeing Marian.

In 1963, Dad's time was taken with two things, driving out to see his girl and studying for EIT (Engineer-In-Training) exam, which he took and passed in April. He had already been promoted once at the Flood Control District, and after passing the EIT he got promoted to Civil Engineering Assistant, making a jaw-dropping $659/month! Having secured an income like that, he was ready to propose to his girl. He started dropping hints about marriage in June. Marian was only 18 and hadn't been thinking about marrying so young, but he sweet-talked her into the idea. In August he officially popped the question, and she accepted.

Dad got an apartment in late September, 1963, expecting to marry sometime in 1964. Mom was working for the phone company (back then there was only one!), and she applied for a transfer on her job, anticipating her coming move to Los Angeles. To her surprise, they processed her transfer immediately and informed her on a Thursday or so that she would be starting work in LA on Monday!

What should she do? Commute from San Bernardino every day until after the wedding? Get an apartment of her own in Los Angeles? Dad had another idea, "Why don't we just get married this weekend?" (He's always been such a practical guy!)

Mom, with the help of her mother and sisters. rushed out and bought a dress and made plans for a wedding. That weekend they drove out to Las Vegas and tied the knot at the Chapel of the Stars. After their honeymoon, they settled into the apartment as husband and wife.

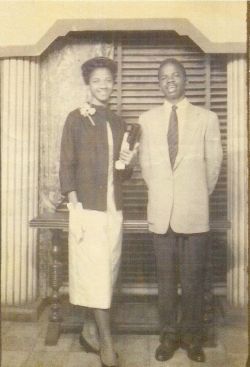

October 12, 1963 -- Who says that a skinny, engineering major with glasses can't get a hot girl?

More coming!

I'll be back with the rest of Dad's life story!

Stay tuned!

Growing and prospering

Please leave a comment. As busy as my Dad is, I'll make sure he reads them.