Bluecoat: The rebellious spirit of Philadelphia

Manna in the newsroom

I like gin. There it is. I like gin a lot. My personal poison of preference is a martini, straight up with olives if it is a good gin, a dirty martini when it is made with rot gut. I am fine with either. I claim that I drink them because the olives meet my minimum daily requirement of fruit.

Okay, you might not buy that, but people in a bar are much easier, especially later in the evening.

One day a few years ago, I accepted delivery of an unexpected package. As I had not received a death threat for weeks, I opened the cardboard box to find—another box, this one made from wood. The brand—literally, it was burned into the wood—was Bluecoat American Dry Gin.

Oh, Happy Day!

Inside the box was—not another box, but a bottle, a beautiful cobalt blue bottle, that looked as if it boldly declared tradition. This was clearly a bottle with a pedigree, its lettering was gold and its cork was protected by a blue seal reminiscent of the lapels of the Revolutionary soldiers.

I was happy. And wrong. The bottle was in fact a clever promotion for a new product from Philadelphia. Or, if it was a bribe, an effective one. The Blue Coat brand is a clear statement that this is no Tory gin, not a Redcoat: no London dry, this. It was American dry, and I am a loyal citizen.

As I indicated, I am a proud and devoted member of the juniper brotherhood. I like the taste of gin, the smell of gin, the glister of the olives’ flesh after bathing in gin.

I like gin. Admittedly, some of the ---ummmm---more affordable gins have the fine finish of nail polish. Excellent quality nail polish, of course, but nonetheless, not am aftertaste that I seek….

A new gin in town

As beautiful as I found the packaging, the gin was better. It was smooth, well-rounded, complex and flavorful, fruity almost at orange. I was a happy fellow, and I decided that I had to learn more about this nectar of the bibulous gods and those who produced it.

I called the distiller and arranged to tour the distillery and interview the master distiller, but I was then in the newspaper business and when work reared its ugly head I was unable to get away.

However, as happenstance would have it, the distiller was about to begin distribution in my area (hence the promotional bottles sent to editors at area newspapers) the master distiller was visiting the area to introduce the new brand. We arranged to meet at a bar, where he would tell me about Bluecoat and we could do a tasting.

Better and better

My friend Fernando and I met master distiller Robert Cassell at a neighborhood small bar. I said, “You’re young!” with my usual forethought and diplomacy. Robert said that he gets that a lot, as might be expected for someone who was then in his twenties.

We bellied up to the bar and Robert produced what looked like a wooden cigar box. This one was stamped “Bluecoat” and contained a set of large glass vials: Robert’s education kit. It contains samples of the ingredients and the congeners, or impurities (nail polish), in gin.

While glasses of top-shelf gins taunted us from the bar top, Robert carefully explained, as he was doing with restaurant staff and liquor store buyers, how gin is made and how each of the ingredients and congeners, even the shape of the still, can change the taste of the gin.

He doesn’t talk much about the brand, preferring to rely on “training the palate and educating the drinker.” Of course, he doesn’t need to. I knew what I thought of Bluecoat; I was just curious about why it seemed so have such rounded flavor and none of the nail polish—that is, congener—bite.

Acing the Nineteenth Hole

Robert was on the golf course when he began wondering why no one could make a gin that is free of distasteful attributes. A student of nuclear medicine, Robert made finding out his mission. With knowledge and experience from his work in quality control at a Philadelphia brewery, Robert enrolled in the International Centre for Brewing and Distilling, a section of the School of Life Sciences at Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh, Scotland. Then he was ready to attack the two critical elements of producing his ideal gin: recipe and equipment.

“I just took everything I didn’t like about the other gins and said ‘What can I do to get rid of that’?”

A Model T on the interstate highway?

Many distilleries boast that they use stills that date back 150 years. “But we don’t still drive Model Ts,” Robert said, noting that most of the working stills, not the ones visitors see on the tour, are Rube-Goldberged to provide the reflux needed to optimally distill gin.

Gin has traditionally been associated with Holland, where it was born, or England where it became a national drink, known as London dry gin (or “Mother’s ruin,” depending on one’s point of view). Breaking away from the Redcoat image of London dry, Robert and his partners created the Bluecoat brand, a revolutionary idea. Robert developed an original recipe and designed a still using experience, knowledge and scientific principles.

Mother's Ruin: Not Your Grandma’s Recipe

Talking with the master distiller is much like talking to a perfumery’s nose. Instead of the earthier juniper berries that smell like a piney car deodorizer, (Juniper is the sine qua non of gin, the ingredient that gives gin its name: genièvre in French, or jenever in Dutch.) Robert chose a plumper organic juniper “from the eastern Mediterranean” with a gentler flavor and aroma.

Instead of the traditional bitter orange peel, Robert chose an organic sweet orange and two other organic citrus peels and angelica root to “add dimension” and “give definition” to the citrus notes.

While many gin distillers use additives to mask the impurities or to make them palatable, at Bluecoat, these organic compounds such as methanol, which can be used as fuel, and proponol, which is used as a solvent in products such as nail polish (Aha!) are separated and sold for repurposing.

At the same time as he was working on his recipe¸ the master distiller was also designing a still that would remove impurities and produce a balanced and gentle flavor. Eliminating the impurities meant eliminating the walnuts, pepper and various other ingredients that other distillers use to mask them and to concentrate on adding the flavors that he wanted to enhance the flavor of Bluecoat gin.

But still, a long graceful neck....

With an understanding of how the design of a still, even the size and conformation, can influence the flavor, Robert set about designing a unique hand-hammered (“hammered,” heh heh) copper still with a long swan-neck column, bringing out the flavor of the organics. The shorter the still’s neck, the earthier the gin; Bluecoat’s still is 22-feet high. After ten-fourteen hours of distillation in the slow-heated pot-still, the gin flows at the rate of about 3-4 liters a minute.

The use of batch job distillation produces a fuller flavored product and allows for better separation of the impurities usually associated with gin. Distilling gin in small batches also allows the master distiller to monitor and control the process.

Not only do congeners taste bad, but they also are the culprit that causes hangovers, so the less an alcohol has been distilled and processed the more congeners would remain, hence the greater likelihood of morning-after uglies for less refined alcohol. (Great taste; Less killing!)

To assure consistency, the distillers combine three batches in a storage tank before bottling, and the taste today is the same as the first batch.

Coming to a Location Near You

Whenever possible, Bluecoat tries to buy locally, although so far the distillery has been unable to find sufficient supplies of organic coriander to feed his still. (I wonder if all organic ingredients mean that gin has returned to its original medicinal purpose.) Likewise the company has had to go abroad to find bottle makers who can produce and etch his uniquely colored bottles in quantities appropriate to his needs. The wooden boxes though come from Acme Box Manufacturing a few miles from the distillery.

Robert says that the greatest satisfaction in bottling his dreams is being able to develop the recipe that makes him proud to say, “Yeah, I did that.”

To my mind, he also has the right to be proud that he had courage, confidence and perseverance to “Be Revolutionary” in creating a new source of American pride.

Although, one might say that I have invested heavily in Bluecoat Gin, I am sad to confess that I have no financial interest in the company. Bluecoat is still (heh heh) not available everywhere, but the company’s website, www.bluecoatgin.com, lists where it is available and provides recipes and more information about gin.

Olives or cucumbers?

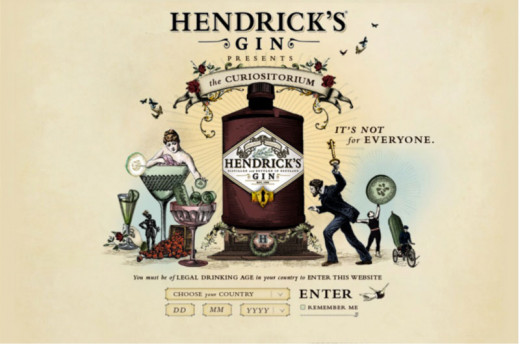

And when I can’t find Bluecoat, there’s always Hendricks, an equally delightful product this one from Scotland. Hendrick’s also has a distinctive bottle that looks like a brown apothecary bottle, but its recipe includes cucumber and is best served with cucumber slices instead of olives.

And the Hendrick’s ‘Curiositorium’ website, www.hendricksgin.com, is decidedly more fun.

And when neither Hendrick’s nor Bluecoat is available, a dirty martini fills the void quite nicely.