Butter Tastes Better

Spread The Word

There's nothing like biting through a cold slice of butter on warm chewy toast or on a freshly baked fluffy scone topped with a dollop of clotted cream and luscious strawberry jam. My consuming passion for butter remains unabated even though love affairs with saturated fats have been deemed politically incorrect by those gastronomic spoilsports, the fat police. To my mind, there's a place for such glorious indulgences in the context of a generally balanced diet and lifestyle.

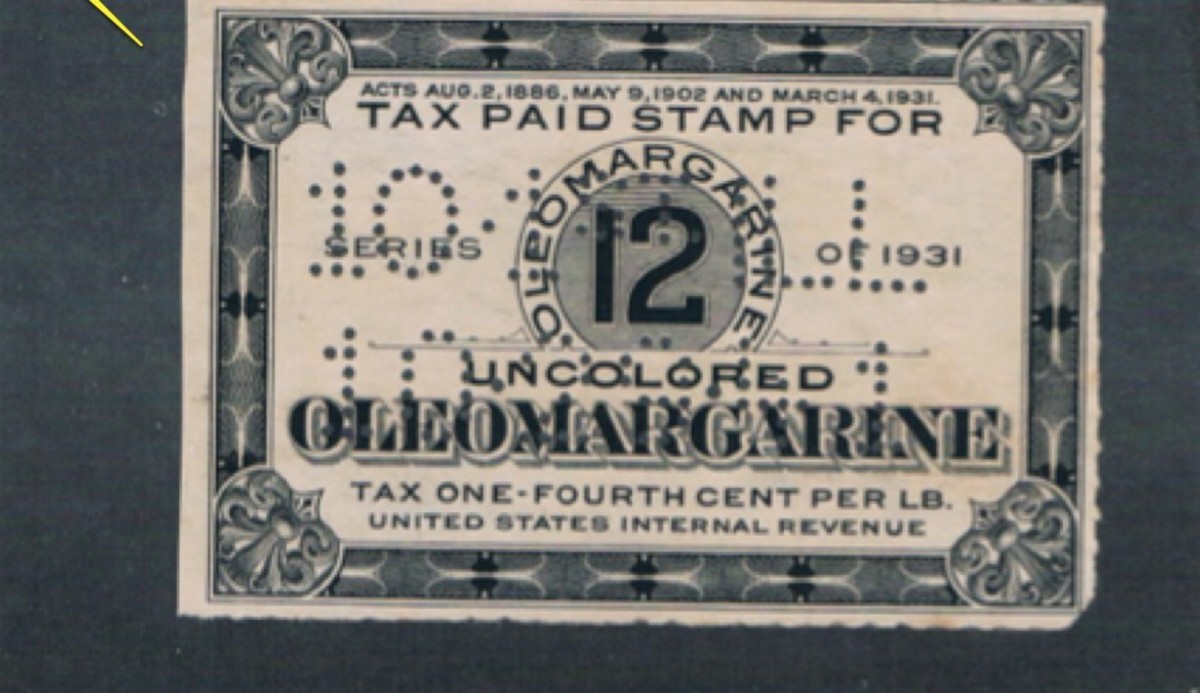

Poor old butter! Despite its wonderful eating qualities and its exceptional culinary talents, this totally natural product has been usurped by its imitator, the industrially manufactured margarine, thanks to concerns bordering on paranoia about the healthiness of saturated fats. In fact, margarine usually consists of about 25-30 per cent saturated fats. The manufacture of margarine basically involves turning from its natural liquid state by converting part of the poly- or mono-unsaturated fat into a saturated fat through a process called hydrogenation. The initial resultant product is not a pretty sight and has to be deodorised, coloured and flavoured to render it palatable. "Lite" magarine simply means high water content.

Margarine's spreadability straight out of the fridge has helped give it the edge over butter in this age of instant gratification. That's terrific for sandwich shops, but would you put a dollop of margarine on the table for a dinner party?

Butter's flavour and texture make it king in the kitchen, particularly in baking. When it comes to pan-frying, margarine has the advantage of a higher smoking point than butter, but it can't provide the fine flavour or the glorious golden brown colour that butter does. The "lite" stuff is completely unsuitable for frying because of its high water content. As frying with margarine is essentially cooking with vegetable oil, you might as well use oil straight off. The smoking point of butter can be raised by adding some oil or margarine, or clarifying the butter.

To clarify butter, heat the butter gently until it foams. Skim the foam off and carefully pour off the clear golden butter, leaving the milk solids in the saucepan. The nutty flavoured brown butter, also known as buerre noisette (which translates to hazelnut butter), is made by heating the butter until the milk solids start to brown. Be very careful not to burn the milk solids - there is a very fine tipping point between delectable nut brown and unpleasant burnt charcoal! The Indian ghee is a clarified butter where the milk solids have been browned before being strained off; hence its pleasant nutty flavour.

Many cakes, biscuits and pastries rely on butter for both flavour and texture and will never be as good when made with margarine. For flakiness in pastry, particularly puff pastry, the fat must be capable of remaining solid in a hot oven long enough for the dough around it to set. As such, lard and shortening (both 100 per cent solid fats with high melting points) are the ideal, while butter, provided it is very cold before it goes into the pastry, is a close second. Margarine, unless it is highly saturated, cannot fulfil this role.

Not all butters are equal. The water content varies among brands and is usually around 20%. An indication of high water content is the degree of spitting when it is heated. Read the ingredients listing - a good unsalted butter should only have 2 ingredients listed: cream and lactic culture. Almost all commercial butters are drawn from frozen stocks but fresh butter can still be found. Fresh butter from the Warrnambool Dairies is still sold in pats from bulk blocks at Melbourne's Victoria Market.

Good butter is also a reflection of terroir, carrying the flavour of the pasture on which the animals graze. The renowned Isigny Sainte-Mère butter reflects the pastures and soil of this region in Normandy (France) and the unmistakeable exquisite flavour distinctive quality of this butter has been recognised with an Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée specification since 1986. In recent years, there has been a revival of small specialist dairy farms producing exceptional quality butters, each one an individual expression of breed and feed of that farm's herd. Seek these butters out at farmers' markets and good food stores.

How many ways do I love thee, butter? This cake is but one.

Brown Butter Almond Torte

100 g unsalted butter

1 tsp vanilla extract

125 g whole blanched almonds

75 g plain flour

140 g caster sugar

½ tsp salt

100 g dried sour cherries (optional)

6 egg whites (from 60 g eggs), at room temperature

¼ tsp salt, extra

70 g caster sugar, extra

100 g flaked almonds

In a small saucepan over moderately low heat, melt the butter and continue to heat until golden brown. The bottom of the pan will be covered with brown specks and the butter will have a nutty fragrance. Strain the melted butter through muslin into a bowl and leave to cool; then stir in the vanilla extract.

In a food processor, grind the almonds with the flour, 140 g sugar and ½ teaspoon salt. Toss sour cherries (if using) into the mixture.

Beat egg whites with ¼ teaspoon salt until they hold soft peaks. Gradually beat in 70 g caster sugar until the mixture holds stiff peaks. Fold the nut mixture in gently, followed by the melted butter. The batter will deflate.

Spread the mixture into a 23 cm round cake pan lined with baking paper. Scatter flaked almonds evenly over the top and bake in the middle of a preheated 190?C oven for about 40 minutes or until a skewer comes out clean.

Leave the cake to cool in the pan for 15 minutes. Turn it out to cool completely on a wire rack. It keeps well for several days in an airtight tin.