Did Cooking Make Us Human?

A Good Old Barbecue

The Handy Man

Where Do We Come From?

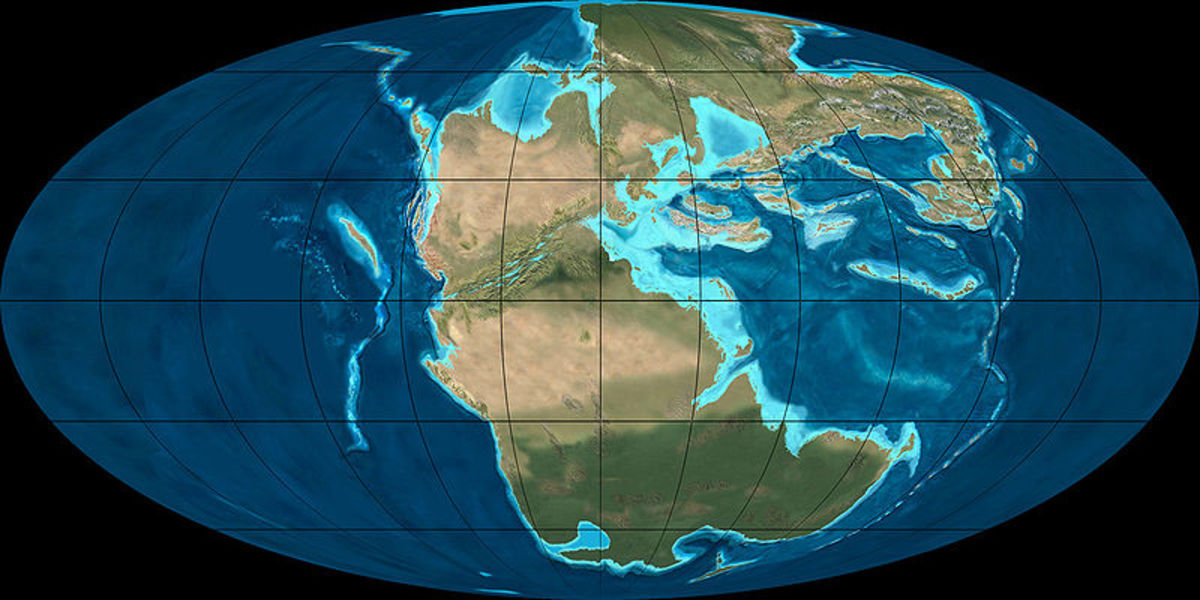

Where do we come from? It’s probably the oldest and the most natural question in the world. For most of our history, we have relied on the supernatural to explain how we got here and why we are so fundamentally different to every other living creature. We now know that our bodies were moulded carefully by natural selection in the forests and on the plains of Africa. Long before any human ever wrote or tilled the soil, our ancestors lived there as hunters and gatherers. Fossils reveal our close kinship with ancient Africans who lived more than a million years ago; these were people who were physically similar to us. However, in deeper rock layers the records of humanity dwindle and fade at around the two million year mark, replaced instead with upright apes known as Australopithecines. This extraordinary transition leaves us with a tantalising question that only science can truly answer; what made us human?

Over the last 150 years, ever since the publication of ‘The Origin of Species’ science has repeatedly attempted to rationally answer this question. Initially, based on the fossil evidence it was assumed that humans had developed bigger brains which then led to the acquisition of bipedalism, which in turn led to the freeing up of the hands which enabled our ancestors to manipulate objects with much greater skill than their ape cousins. But then, in 1925 the discovery of a fossilised bipedal ape called Australopithecus africanus, by Raymond Dart demonstrated that it was actually bipedalism that preceded brain growth; africanus was a creature that lived more than 3 million years ago, long before any recognisable humans with their inflated craniums walked the Earth.

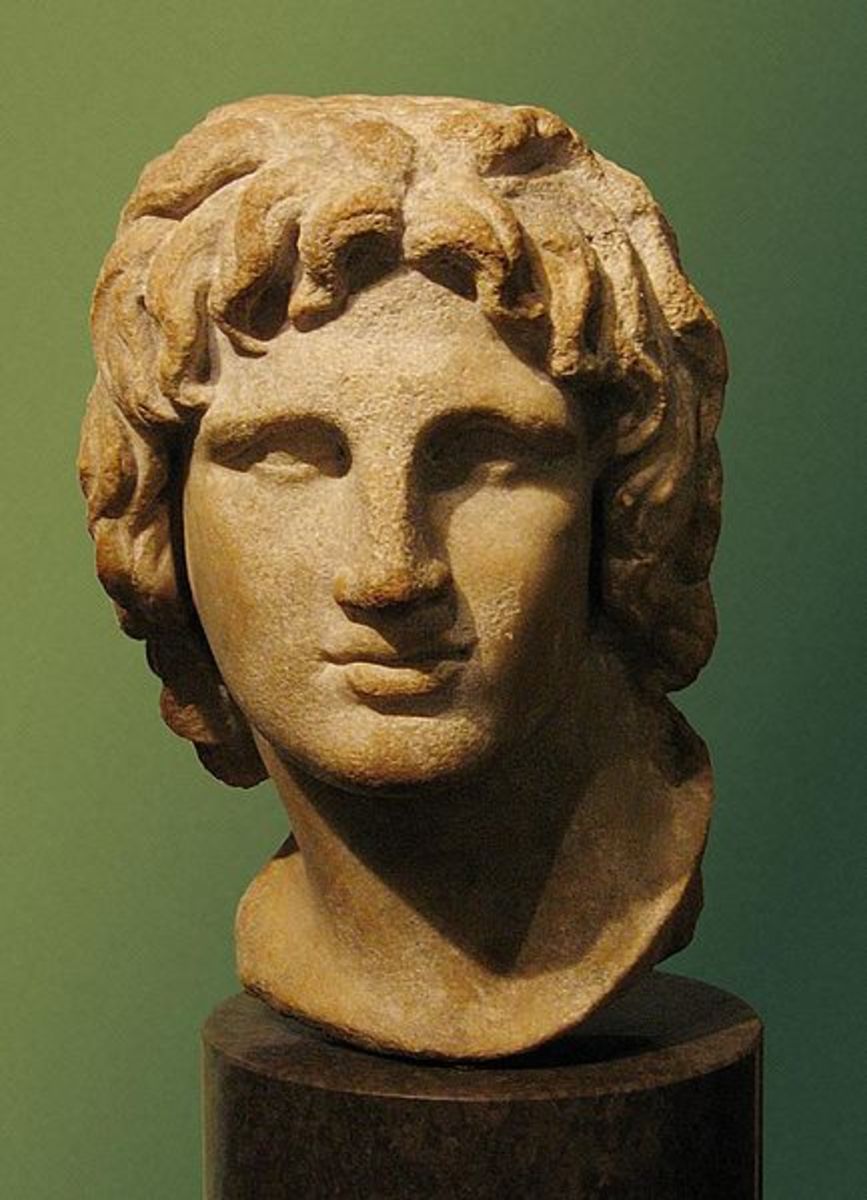

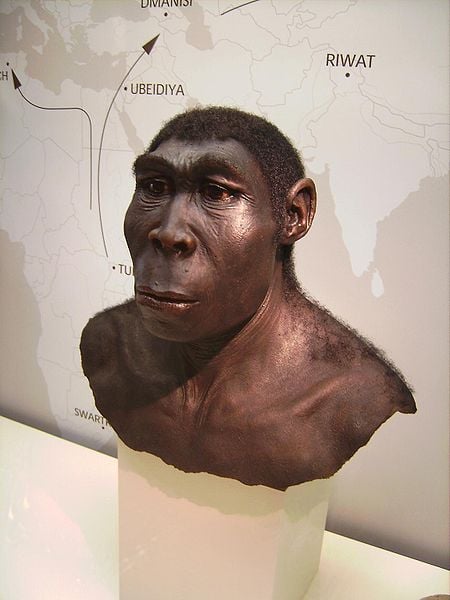

Scientific evidence now states that long after acquiring bipedalism, our ancestors experienced an unparalleled and unprecedented growth in brain size, between 2.6 and 1.8 million years ago. At this time there was a creature abroad in Africa called Homo habilis, this creature was the first of our line to both use and actually make its own stone tools, it was also the first of our line to experience a significant increase in brain size over its cousins. But it was the creature that followed habilis that aroused the greatest interest, because around 2 million years ago, the first truly human creatures appeared. Science have christened these taller, leaner apes Homo erectus. If we were to gaze upon one of these creatures today, the only thing that would strike us as odd is their flatter skull and slightly protruding jaw; but other than that, they were as human as you or I, in a physical sense at least.

But how did Homo habilis transform into Homo erectus? It’s probably the most important, and yet the most overlooked question in all human history, because finding the answer, helps us to understand how we became what we are. Science has long suspected that the main driving force behind this remarkable change is diet, namely the gradual switch from a mainly vegetarian diet to a more omnivorous diet that included sizable portions most likely scavenged from the kills of large predators.

But can the introduction of meat into our diet really be the sole cause of the biggest and quickest increase in brain size in the whole history of life? Sadly no, it’s not quite as simple as that, for you see we've actually been eating meat for much longer than we think. Chimpanzees are our closest living relatives and have recently been unmasked as insatiable carnivores and expert hunters; successfully hunting down colobus monkeys in the treetops using sophisticated teamwork and cooperation. We share a common ancestor with chimps which we think lived some 6-8 million years ago, and it’s likely that that common ancestor ate meat too; therefore it’s probable that we both inherited our love for meat and hunting from this creature. So, sadly eating meat on its own cannot answer this mystery, but maybe we are thinking too simply, maybe the key to answering this question is to not look at what we were eating, but how we were preparing our food?

A Raw Bonanza

Can We Survive on Raw Food?

- JUSTUS-LIEBIG-UNIVERSITÄT GIESSEN

The official website of the Giessen Raw Food study- includes links to the results of their studies.

More on the Evo Diet Experiment

- BBC NEWS | UK | Magazine | Going ape

What if humans cast aside processed foods and saturated fats in favour of the sort of diet our ape-like ancestors once ate? An article outlining the results of the Evo Diet experiment filmed by the BBC.

Can Humans Survive on Raw Food?- An Experiment

It sounds like an absurd question, doesn't it? Of course we can survive on raw food; animals do it, we human are animals so conventional wisdom dictates that we can do the same. Indeed, much of the food available to buy from supermarkets are perfectly edible raw, from apples, tomatoes and oysters to steak tartare and various kinds of fish. But can we survive indefinitely on an exclusive raw food diet? Before scoffing at such notion, please consider a rather interesting experiment filmed by the BBC in 2006.

The Evo Diet experiment involved nine volunteers with dangerously high blood pressure travelling to Paignton Zoo, England, where they lived for twelve days eating an ape like diet. They lived in a tented enclosure close to our chimp cousins and like them ate everything raw. Their diet included peppers, melons, cucumbers, tomatoes, carrots, broccoli, grapes, dates, walnuts, bananas and peaches. In the second week, they were allowed to eat some cooked oily fish and apparently one man managed to sneak in some chocolate. The experiment supposedly involved serving up the food that we are supposedly evolved to eat, it was a diet that any chimp or gorilla would have salivated over and would have probably grown fat on. The people ate until they were full, taking in up to 10 pounds of weight per day. The daily intake was calculated by nutritionists to include the adequate 2000 calories for women and 2300 men.

Over the twelve days, all of the people experienced significant drops in cholesterol and weight, with the average being around 0.8 pounds a day. But while this weight lost was an undoubted positive effect, it turns out that the long term effects of living off an exclusive raw food diet can be catastrophic. According to the Giessen Raw Food study in Germany, adoption of a raw food diet leads to a marked decrease in weight and also in BMI (Body Mass Index), which measures weight in relation to height to determine just how fat a person is. Basically, their findings indicated that as the amount of raw food increased, so the BMI decreased, with women losing as much as 26 pounds, and men 22 pounds. Incredibly their findings revealed that a third of all the people they studied showed signs of chronic energy deficiency, leading them to make the rather unambiguous conclusion that a raw food diet cannot guarantee an adequate energy supply.

Not only does it seem that eating raw food exclusively deprives us of much needed energy, but it seems that it has even greater consequences for our bodies in women especially. The Giessen study found that around 50 per cent of women eating raw diets actually stopped menstruating completely. A further 10 per cent experienced irregular cycles that left them unlikely to be able to conceive at all.

So, if we humans are truly like all other animal, who can survive on raw food? Why do the Evo Diet and Giessen studies report such alarming results? If we humans have been living off raw diets for most of our existence, then how on earth did we manage to survive? Surely our ancestors would have succumbed to energy depletion and the inability to reproduce sufficiently? So you see, we humans are different from all other animals in one very important aspect. It’s not what we eat, but how we prepare it.

The Element That Changed Our Lives

The First Cook

More on Human Evolution and Cooking

More on Human Evolution and Cooking

- Richard Wrangham - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Wikipedia article on Richard Wrangham- the man who first proposed that humans evolved as a result of the adoption of a cooked diet some two million years ago. - Catching Fire by Richard Wrangham | Book review | Books | The Guardian

A review of Richard Wrangham's excellent book 'Catching Fire' which promotes his theory that controlling fire and cooking made us what we are today. - Home - Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University

The website of the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology at Harvard where Richard Wrangham works.

Becoming Human

Humans are unique among animals in the fact that we both process and cook our food before consuming it. But before explaining how we first learned to cook and why it played such an important role in our evolution, I want to travel back to 2.5 million years ago and attempt to explain just how the first member of our genus Homo habilis developed a brain that was 50 per cent larger than any other hominid alive at the time. We know that hominids did not possess control over fire, at this time, but there was another way that habilis could have stolen a cognitive march on his rivals. Homo habilis was the first toolmaker and they not only crafted stone knives to cut flesh from the bone but also used stone hammers or wooden clubs to batter and tenderise their meat. They probably cut hunks of meat off the carcasses of large herbivores and sliced them into steaks before pounding them accordingly to render them more palatable and reduce the costs of digestion. Today, our forest dwelling ape relatives have to spend up to 70 per cent of their day chewing tough raw food and just as long trying to digest it; it’s the main reason why our cousins, especially the gorilla have large protruding bellies and also large strong muzzle-like jaws.

But what about the next great change? Well, in order to theorise an answer to that question, try imagining travelling back around 2 million years to what is now modern Kenya; you stumble across a group of Homo habilis, some of whom are crafting stone tools by banging rocks together in a calculated and precise way. From time to time, sparks from the pounding rocks ignite small fires in the surrounding brush. Imagine a cocky juvenile daring to grab the cool end of a branch and teasing a companion with the smouldering twigs or blazing leaves, in the same way that young chimps playfully bully one another with sticks they use as clubs. The adult habilis’ watched how the infants reacted to the burning logs and learned the practice of scaring others with fire, applying it to the more serious job of frightening predators such as cats and hyenas, similar to how chimps use clubs to scare off leopards. Initially the habilis’ fires went out, but over time they learnt that it was in their best interests to keep the fires going somehow. They effectively tamed and cultivated fire to defend themselves against dangerous animals.

Once Homo habilis had mastered the art of keeping a fire lit, the discovery of cooking may have occurred accidentally through occasionally dropping food morsels into the fire, and eating them after they had been heated. They likely learnt quickly that heated food tasted much better and repeated the habit accordingly, thus the greatest discovery of all was made, cooking.

Thanks to the discovery and subsequent adoption of a cooked diet, hominids no longer had to spend so much time chewing tough raw food, now they could tenderise it both by pounding it and by breaking down connective tissue through cooking. Hominids had managed to save around 20 per cent of the energy required to digest their food, but that energy didn't just vanish, instead it transferred to the brain. Essentially, the development of cooking involved a remarkable trade off, smaller guts for larger brains.

The steps taken to grow a larger brain in a hominid were actually not all that major; all it required was a slight tweaking of the developmental stage between child and adulthood. All baby apes you see, actually bear an uncanny resemblance to humans, possessing large craniums and flat faces, as well as a bunch of other traits normally associated with humans such as the ability to smile, an innate curiosity and playfulness. Normally, the young ape loses its human like features during adolescence when it develops the large protruding muzzle of an adult, leaving it with a rather small and flat cranium. At some point in our evolution this last phase of development was knocked out leaving us resembling juvenile apes- this is a process known as neoteny where an organism becomes able to reproduce while still retaining juvenile features.

The new cooked diet also led to larger bodies which evolved as a result of no longer having to rely on the sanctuary of the trees. Tree dwelling animals cannot afford to grow too big due to the obvious need of being able to support themselves in the trees. They also became hairless which probably evolved due to the presence of the warm fire, humans no longer needed fur to protect them from the cool African nights and so they not only lost most of their hair but also some nasty parasites that plague hairier mammals. As well as developing larger bodies, we developed long, powerful legs enabling us to run, turning us into hunters rather than scavengers. The development of larger, infantile brains also led to calmer temperaments, more flexible and ultimately more complex behaviour and also the development of the first recognisable societies based on sharing and cooperation rather than competition. The softness of cooked food selected for smaller teeth; while the discovery of cooking led to a new kind of relationship between males and females, one of pairing up and remaining together for a time.

Elsewhere in Africa, other hominids continued to live off and thrive on raw foods for hundreds and thousands of years. But the cooking ape had arrived, Homo habilis had now transformed into Homo erectus, and the rest is as they usually say, history...

The Evidence of Early Humans Controlling Fire in Africa

- Swartkrans Paleoanthropological Research Project - Main Page

The official website of the Swartkrans Research project led by prominent paleoanthropologist Bob Brain who first determined that early hominids were the hunted rather than the hunters. - Evidence from the Swartkrans cave for the earliest use of fire

A scientific paper from the journal 'Nature' that provides conclusive evidence that humans were controlling fire at least 1.5 million years ago. - http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/3557077.stm

Early human-like species from southern Africa could have been using fire 1.5 million years ago after spectacular evidence was uncovered at Swartkrans in South Africa. - Koobi Fora Research Project

The official website of the Koobi Fora Research Project based in Kenya, Africa. - The Early Domestication of Fire

An essay on the early domestication of fire by Winslow Johnson that mentions Koobi Fora- a site in Kenya that provides evidence of humans controlling fire as early as 1.6 million years ago.