Will Genetically Modified Foods Save a Starving World?

Click your fingers as fast as you can

A child is being born with every click

Sound unbelievable? Well it's near to the truth, some forty thousand babies born every day around the globe. We live in a world where the population of our species is immense and escalating, estimated to reach 8 billion by 2015 (that's 8000 million). The resources we expend on a daily basis are, therefore, understandably colossal.

For most in the developed world this reality remains largely unconsidered, industrialisation having enabled us to meet our growing daily needs. However, for many in undeveloped parts of the world –some 80%– daily requirements are a struggle if not an impossibility to achieve.

The reasons are many, ranging from politics to infertile land, but causes aside, the UN projects that such world growth will affect Asia (especially South Asia), Africa, and Latin America the hardest; regions that are poor and little industrialised.

But rather than dim expectations, some scientists are instead saying that starvation and disease could be unknown in the future of our world, and the technology they propose as getting us there is Genetic Engineering.

Says Peter Day, the director of Rutgers' Biotechnology Centre for Agriculture and the Environment, "Biotechnology offers new hope for the developing world."

- Think the world is overcrowded? These 10 maps show why you’re wrong | World Economic Forum

The world is not as overcrowded as you think. 50% of the world’s population lives in just 1% of its land. These are 10 maps that show how people live.

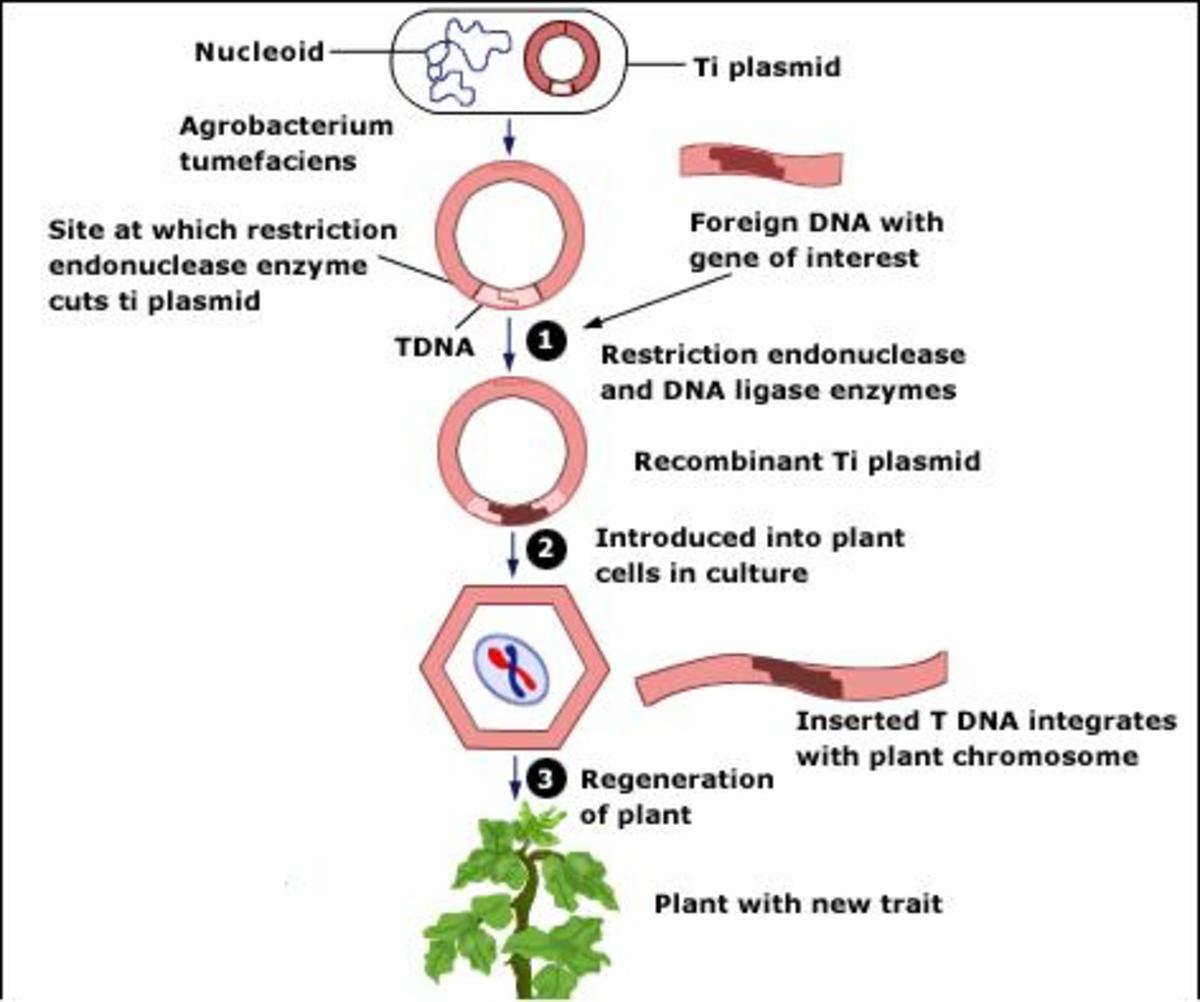

Recombinant DNA technology

Genetic engineering (GE), or recombinant DNA technology, involves the separating, rearranging, and transferral of bits of DNA from one cell to another, accomplishing through human intervention what would be unlikely to occur through natural processes. Unlike hybridising (cross breeding) genetic engineering is a cut and paste process where unfavourable genetic traits are removed, replaced, or altered, producing an "improvement" on the original.

One of the first examples of GE was the transferring of the section of DNA responsible for insulin production in the human pancreas and its re-insertion into a bacterium. The new bacterium began to produce insulin, which could then be extracted for use. This technology is now used to treat diabetics who lack the ability to produce sufficient insulin for themselves.

Still largely in its infantile stage, many scientists hail GE as the promise of a better future through enhanced medicinal and agricultural products. In agriculture, for example, potential applications of GE include development of crop plants resistant to drought, cold, insects, herbicides, and disease.

For third world countries this technology may prove their deliverance. With crops more resilient to the hardships present in many developing lands (arid environments and salty soils) and farmers not having to spend on fertilisers and pesticides, while producing larger yields in harvest. GE is a technology that these countries cannot afford to ignore.

However, despite the benefits that may be derived from genetic research and trialing, the term "genetic engineering" arouses fear and suspicion, the subject generating a great deal of public concern and even political debate globally.

What the Biotech Companies Tell Us

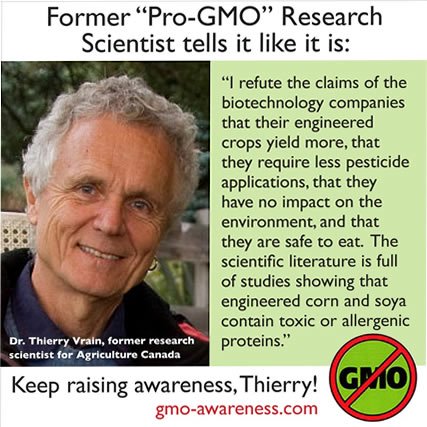

No Consensus on Safety

Says John Grogan, managing editor of Organic Gardening Magazine, "The biotechnology industry wants the public to believe that GM foods have been exhaustively studied and proven safe, but that is not the case. At a minimum, these altered foods need to be labelled so consumers can know what they are eating and, more importantly, genetically altered foods need to be subjected to extensive independent safety testing before they are released to the public."

Geoff Kidd, head of gene forge technology for Aptagen, Inc., adds his concerns, "Whether by traditional breeding or by genetic engineering, genes are being altered in ways that could affect other metabolic pathways in the new food organism. Prediction of which pathways could be affected and to what degree are poor at best, since there is a great deal that is still unknown about genetic and enzymatic regulation."

Risk versus Need

After such experiences as the Mad Cow disease and Bovine hormone scare, it is not surprising that people are troubled by what may appear to some as just another human intrusion into nature, tinkering with what they don't understand.

Some are concerned this tinkering may lead to bacterium containing cancer-producing viruses. It is also possible that plasmodia carrying drug-resistant genes will be introduced into a pneumococcus, causing the pneumococcus and pneumonia to be resistant to antibiotics.

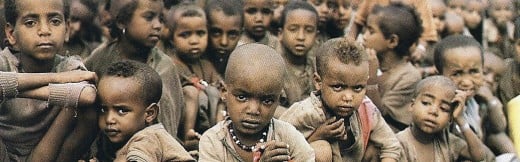

Yet while the developed world debates the issues and dangers, the third world starves. For them there is not the liberty to choose between GE foods and the traditional variety. Their options remain very simple, they need food or they die. Offer a starving man a genetically modified banana, and he won't wait to hear the possible dangers that may come from consuming it before eating.

And here is where the greatest danger of GE may lay

In the hands of the West, time can be sacrificed for precautions sake, millions poured into research to hunt out and eradicate all risks. But in the hands of the undeveloped nations, precaution may well be thrown to the wind in favour of feeding the masses.

For that reason alone some believe the West must take the lead, so as to offer developing nations a technology as free from risks as possible. In the words of Stephen C. Joseph, president and CEO of the National Centre for Genome Resources, 'The potential benefits of agricultural biotechnology are so powerful that to halt research would likely forestall immense potential benefits to humankind'.

Recommending an open method of thorough analysis into genetically modified organisms with adequate safeguards, Joseph says, "We must move forward quickly, but thoughtfully, to examine the perceived dangers from plant biotechnology". With the GE debate growing, he believes there is a real danger that research will be disrupted, which would not be in the world's best interest, especially for hungry people in developing areas.

As Peter Day testified before Congress "Stopping biotechnology based on fears that are exaggerated and unjustified would be a travesty of historical proportions."

Says Arthur Kornberg, leading American biochemist 'Genetic research is being done by serious and responsible scientists, and techniques to minimise accidental spread of potentially dangerous microbes are being improved. The National Institutes of Health, in the United States, has published safety guidelines to minimise the hazards of research. The potential dangers of such research must be balanced against the actual tragedies caused by malnutrition and by fatal and debilitating diseases.'

Hopefully genetic engineering will prove a boon for mankind, but if not, then it is better to discover why not now, than leaving it to be discovered by future generations who will be the reapers of whatever we choose to let loose on the world today.

What are your thoughts?

If it would...

If GM food could save children from starving, is it still worth the risk?

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2010 Richard Parr