Five RPG Characters to Watch Out For

In most genres and settings, there are certain character types that are expected. For example, if you’re playing a game set in the world of The Dumb Jousting Movie with the Kid from the Patriot, you can expect some commoners pretending to be knights, armorers with product placement deals, naked literary greats, and comical Tudyks. Some games lock you into the stereotypical options, but most allow you to play any character that fits the setting. Want to play a wandering friar? Go for it. A foreigner who owes another character a life debt? Worked for Morgan Freeman. A witchfinder? Sure, as long as the other characters are cool with the whole “tortures and burns random peasants” thing. A gluten-free space elf werewolf with machine gun arms? Ok, that one breaks so many basic assumptions about the game setting that the other players probably won’t go for it. If you can talk them into it, though, more power to you.

Even though you can theoretically play just about any kind of character that fits into the game world (and maybe even some that don’t), there are still certain character types that have a long and storied history of irritating other players and disrupting games. Some of these character types just don’t work, but many of them are considered “problem characters” because most people play them very, very badly. Here are five character types that you should approach with caution, if not avoid entirely.

A Character Who Doesn't Fit The Game Premise

It should go without saying that your character needs to fit the premise of the game, but years of experience suggests otherwise. Make sure that the character you create has a reason to hang around with the other characters and has something to offer that makes the other characters want to keep him around: a personal connection with other members of the group; a common goal; useful skills, knowledge, or resources; maybe even just a winning personality. If your character is just some random unlikeable yutz with nothing to offer, his continued presence will seem contrived and make the story less believable.

Here are a few examples of characters who don’t fit the premise:

-

If you’re playing a game set in a desert, don’t play a pirate unless there’s a really compelling reason for him to be wandering around in the desert instead of, you know, pirating.

-

If the game involves characters traveling from planet to planet in a spaceship, don’t play a member of an obscure religious cult that forbids space travel.

-

If the game is about rebels fighting against an evil empire, don’t play a loyal imperial soldier.

-

If the game is about square-jawed men of action fighting Nazis, don’t play a mild-mannered accountant who abhors violence.

-

If the game is supposed to have a serious tone, don’t play a character named Dingaling McFartypants. In fact, it’s usually best to avoid “joke” characters entirely unless you’re playing a comedy game where it actually fits. Once the joke stops being funny (which will happen very, very quickly), all you’re left with is a character based on a dumb idea (see also “One-Note Characters”).

The Chosen One

Fiction is lousy with characters who are born with great destinies, so it makes sense that RPGs will have their share of Chosen Ones and Boys Who Lived as well. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with that, but remember that role-playing is a group activity. Star Wars is Luke’s hero’s journey, but it’s also the story of Han and Leia’s courtship and the Forrest Gump-like tale of two droids stumbling from one world-changing event to the next in a galaxy far, far away. Unless your character’s destiny is part of the game’s premise, make sure it can be accomplished as part of the story that the group’s already decided to tell. If the GM’s only options are to change the premise of the game to make the story revolve around your character or to ignore your character’s story hook entirely, you need to go back to the drawing board.

A variation on this theme is the character designed to exercise undue control over the other characters, usually by virtue of status. As long as the other players have agreed to play (and designed characters who are) loyal subjects or can safely ignore your character without suffering any serious consequences, there’s nothing wrong with playing a character who outranks everyone else. If the other PCs are basically your character’s slaves, however, the other players probably aren’t going to like it. Most people want to play heroes, not peons.

The Double Agent

Playing a character who’s secretly working against the party can add an interesting twist to the game, but it’s something that has to be handled with care. For one thing, you need to make sure that you know the other players well enough to judge whether or not they can handle it. Some people take things that happen to their characters personally, and if your character’s actions are likely to cause friction between actual non-imaginary human beings, you should save the mole for another game with a different group. You also need to understand that your character’s betrayal will probably be found out and there will be consequences. If you’re not willing to accept that your character’s story will almost certainly end badly, a double agent isn’t for you.

The (Almost Always Grim) Loner

Fiction is full of characters who don’t play well with others, so the idea of playing a loner seems natural. As I’ve already mentioned, however, RPGs are a group activity. If you tell the party “sorry, I don’t work well with others” and stalk off into the rainy night with your trenchcoat flapping in the breeze, the logical response is for the party to shrug and go back to whatever they were doing, especially if the only thing you have to offer is a bad attitude. They’re not obligated to go chasing after you, and it’s unfair to both the GM and the other players to monopolize a chunk of every session with your character’s solo adventures.

Even if you disregard the logistical problems that loners cause in role-playing games, the fact is that many fictional loners actually work pretty well with others, no matter how often they remind us otherwise. Batman prefers to work alone, except when he’s working with the Justice League, or the Outsiders, or Superman, or any of his rather extensive gang of allies, sidekicks, and support staff. If you’re going to play a loner, follow the Batman model and signal your loner status by being really grumpy rather than constantly skulking off on your own. If your character constantly threatens to leave, eventually the rest of the group is going to offer to buy him a bus ticket.

The One-Note Character

Some players have a tendency to latch onto one aspect of a character to the exclusion of all else. Often it’s a character ability, usually one involving explosions or criminal activity. Sometimes it’s a sincere but ultimately misguided and Dan Brown-like attempt at characterization. Especially with younger players, the one note often takes the form of the character’s love of something like beer or sex that the player has limited first-hand experience with but suspects is really nifty. If your character’s response to almost everything that happens is a variation on the same theme (“I blow it up!” / “Time for some self-flagellation!” / “I try to have sex with it!”), you’ve got a one-note character on your hands.

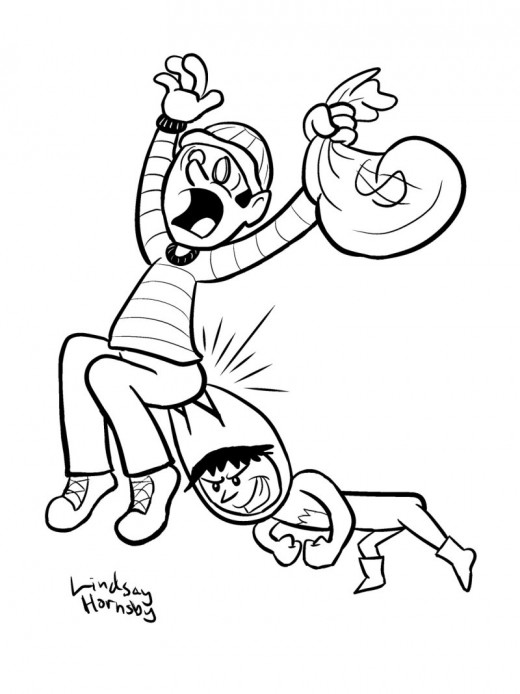

A common sub-type of the one-note character is the “chaotic stupid” character whose one-note involves doing random things that irritate the other characters, sabotage the party, and disrupt the story. Players who choose chaotic stupid characters often rationalize their actions by explaining that their character is “crazy,” apparently in the belief that adding a simplistic and offensive take on mental illness to an already unlikeable character will somehow make things better. It doesn’t.

Many people who play problem character types excuse their actions as “just playing my character.” That’s a cop-out. Not only is the player trying to blame his decisions on a fictional character, he’s trying to blame them on a fictional character that he created. It’s like if Bill Keane tried to blame the complete lack of humor in Family Circus on “Not Me.” Most people who make problem characters seem to do so in an attempt to make themselves (through their characters) the center of attention. Some do it by trying to make their character central to the story, others by creating characters who will create problems that must be addressed. Especially with characters whose actions result in negative attention, it’s basically a form of trolling. Don’t be a troll.

Which problem character type annoys you the most?

© 2015 Steve Johnson