Storytelling, Pacing and Difficulty: Video Games and Their Time-Killing Tendency

Unlike books, films, and television, finding the appropriate pace in a video game, to unveil a narrative or even to simply progress the game itself, is a much more complicated matter. You can feel rather comfortable putting down a book and then picking it right back up later and not feeling like your experience was interrupted that much, and if you’re like me you’ll make it a point not to stop in the middle of a film for a restroom or sandwich-making break or (God forbid) watch a movie in parts because there’s a narrative flow there, but even if you did end up doing so because you just had to go or you had to make a sandwich or you had to leave the house for a couple hours, it really doesn’t feel like the biggest deal in terms of how the film was paced as long as the film itself was paced well. Television already has the minor inconvenience of commercials, but really TV shows have found some very interesting ways to enhance the viewing experience of a show with commercial breaks, such as small cliffhangers in the story before that inevitable ridiculous Old Spice commercial.

But when it comes to video games, there’s a very different dynamic in terms of how a game progresses, and sometimes the pacing can feel like it lags a lot more than in any of the aforementioned forms of media. This is a result of the malleability and flexibility of the narrative in relation with the player’s own progress and decision-making; this makes video games have a much longer runtime—a variable amount of time from player to player—than films or television or theater drama (and sometimes books) that can really dig into the hours of our daily lives.

Films generally have a runtime from 90 minutes to the frustratingly common two-and-a-half hour long runtime of most Hollywood blockbusters (that’s a whole other article I can write right there), with exceptions and outliers on both ends of the spectrum. Television is an extension of film in some sense and is basically one really, really long movie (potentially with insufferable amounts of filler) cut up into tinier pieces; the time between each piece being parsed out over the course of a season. Theater follows the same rules as film; they’re all forms of media with a fixed runtime. All of these things can be viewed in one sitting (yes, television too. You think I didn’t know about you bingeing over Game of Thrones or Breaking Bad or Orange is the New Black or something?), and understandably this makes works of these media relatively easier to pace compared to novels and especially video games, which are generally things that you can’t finish in one sitting, and thus require breaks or spreading out your experience over the course of a week or a couple weeks or so.

But even then novels and books tend to have a much easier time to have appropriate pacing compared to video games, because unlike books, video games have an even more volatile runtime that depends on whether or not the player can even finish the game (and sometimes, whether or not she even wants to). When you read a book, you don’t exactly wonder if you can ever finish the book; maybe you don’t feel like finishing it, but it’s not like you’re incapable of doing so. Video games have that possibility of incapability sometimes, and even if you know you’re determined that you’ll beat a game, there are times when you’ll be forced to retry sections of the game over and over simply because you made a mistake or you lost sight of an objective or the game has a steep difficulty curve. This can really hamper with the pacing of a video game and sometimes it can discourage someone from finishing it.

And this is where most big name game developers of late will go “Well what the hell, but I want people to finish my game!” With the past few generations of video gaming breaking into the mainstream and attracting a much wider audience than its inception in the second half of the 20th century, developers have found themselves in a bit of a dilemma when it comes to pacing their games. Generally speaking, most AAA titles have some sort of narrative to draw audiences in to play the game, stuff like Bioshock Infinite and The Last of Us and Assassin’s Creed and especially RPGs like Final Fantasy are all extensively plot-driven experiences, and this is something game developers take the time and effort to flesh out (whether it’s entirely well-written or not is somewhat irrelevant in this case) because they know that most people nowadays don’t play video games necessarily for engaging and expressive gameplay or even variety in gameplay, but rather for the story. With all the effort and money it takes to make AAA titles, game developers need you to finish their game for more than just the fact that they “worked very hard on it.” Especially with games like Assassin’s Creed, game developers need you to finish their game so they can sell you even more games in the form of sequels.

And there’s nothing really inherently wrong with sequels or story-driven games, but the problem is that in many cases, this focus on trying to tell a streamlined story without really considering the gameplay not only constricts the variety of gameplay on the video game market but also removes the challenge, enjoyment and the rewarding sensation of finishing a video game. What I mean is an ongoing trend in mostly AAA titles that sacrifice difficulty and agency for storytelling; generally in the AAA sphere of the industry, difficulty and narrative flow are inversely related. Nearly every big title on the market these days has a way of dumbing down the game’s difficulty in order to appeal to larger audiences. Again, there’s nothing inherently wrong with appealing to newer audiences; but the problem is that sometimes this is perpetuated so much to the point that there’s no choice in whether or not you get really easy puzzles or battles to fight and force-fed directions on how to play the game, what you’re supposed to do, and where you’re supposed to go.

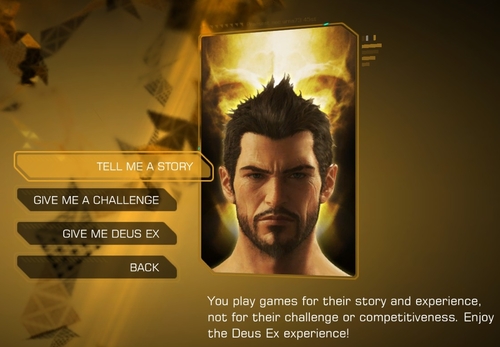

Probably the least intrusive trend in modern game design is the difficulty setting in the very beginning of a game, in which there’s an even easier mode than easy, often described to the player as an appropriate difficulty for those who “only want to play the game to experience the story”. The reason why this is the least intrusive is pretty straightforward: it’s a choice and (most of the time) everybody wins, because for all those people who really want to play the game, they can just play it on a normal or harder difficulty while the others can play it on the simplified mode. It’s ultimately personal preference on whether or not you think that this simplified difficulty is constructive or necessary—I think it’s generally unnecessary because I think it takes away the enjoyment out of the game by negating challenge but I suppose it doesn’t really hurt as much.

Unfortunately, more extreme examples of this inverse relationship between difficulty and narrative have only been growing in the industry. Bioshock Infinite has an arrow that points you to where you need to go with the push of a button, and while that’s probably not too bad in a linear first-person shooter, sometimes you’re asked to find things and this loses all sense of agency if you can simply rely on a button to tell you where to find them. The entire line of Bioshockgames suffers from having the lack of a real Game Over unless the difficulty is ramped way up; one can die, emerge from a spawn point and attack the enemies who have slain her with a war of attrition—the enemies still retain the wounds from the player’s last encounter before she died, and yet she can face them again with full health, ensuring her eventual success. In fact, many games within the shooter genre are pretty much the epitome of this overreliance of narrative at the cost of difficulty and variety of gameplay in the industry. Last year, the biggest titles were arguably Bioshock Infinite and The Last of Us, and while my inclusion of these games in my last article about video games as an artform tried to illustrate their attempts to offer interesting narratives and expressive gameplay, actually playing the games themselves isn’t really that fun, as they offered nothing new to the shooter genre or the industry as a whole and in some cases even had some really backward design choices; you still shot things in and out of cover and there was a set path you had to follow with occasional diversions; there are no real consequences for dying that prevent you from running and gunning, spraying and praying like a madman.

That’s not to say that traditional and action-RPGs don’t suffer from a similar stagnation in difficulty and agency. Final Fantasy XIIIsuffers from a very linear path of progression, with no exploration and a similarly linear leveling system which gives the illusion of choice and customization. XIII in particular was criticized by many for its linearity compared to many of the games in the series, especially when Final Fantasy XII had an enormous world to explore for its time; in response,XIII’s director Motomu Toriyama explained that they “have deliberately used a linear game design for the introduction sections so they can be enjoyed in the same manner as watching a film.”

The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword infamously features a companion for the player that virtually spoils nearly every puzzle in the game by giving hints and pesters the player with reminders of what must be done to proceed in the game. The game also forces the player to use a mechanic called “dowsing” to tediously point the player in the right direction. As I was recently playing Ni no Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch, I found myself frustrated over its excessive handholding with the map marker that constantly told you where to find things that I had to turn off and the constant reminders to tell you what to do and urge you to do it this instant.

Even if developers are making these decisions in game design in order to speed up the process of playing through a game in order to express ideas or tell a story, the problem is that if you compromise the gameplay for telling a story it begins to stop being a game and more like a visual novel or something that simply asks you to follow some directions, watch the story, rinse and repeat. But it lacks even the entertainment of a visual novel because there’s no agency or decision-making for the player, the game now being a list of menial tasks to carry out. And when indie developers who make much shorter, more gameplay-oriented titles like Jonathan Blow (Braid) say that even many games in general are too long and their status as “temporary diversions” are a result of their lacking depth or meaningful experiences then there’s a serious problem with how games today are being made.

Admittedly, this became less and less about how much time we spend playing video games and more about how much of that time was worth spending. Time is very important in our lives; but forcing someone to play a 20-hour game with no decisions, payoff, or depth is more of a waste of time than having to play a 70-hour game loaded with deep experiences and insights or even simply engaging gameplay that requires critical thinking. Objectives and actions within the game shouldn’t be a chore on the way to the next event in the story, they should be something that the player also wants to do within the context of the story. Like any good film or television series or novel, games have no excuse for dragging on even if it’s a sandbox to play in; they need to have some sort of narrative cohesion and avoid filler, and for the player specifically, they need to make the player’s actions meaningful within the story in order to engage them, otherwise the game ceases to be a game entirely.