Cervical Cancer - Latest News from a National Cancer Registrar

Cancer Awareness

How is your cancer awareness, and how much do you know about cervical cancer? I’ll admit that until recently, I didn’t know a whole lot about the condition, but my youngest daughter, Melissa, enlightened me. She’s a nationally certified cancer tumor registrar, and she really stays on top of the latest information about different types of cancer, through research, meetings with oncologists, and attending cancer seminars around the country. She has to because of her job as a tumor registrar with a regional hospital. Besides, she finds the topic fascinating and understands the importance of educating the public. Also, because Melissa’s sister has had several “scares” with precancerous cells discovered in a couple of abnormal pap tests, Mel believes that early detection is paramount to an effective treatment strategy. She’s always urging her friends and family members to get appropriate cancer screening, and she certainly practices what she preaches. She’s very good about spreading cancer awareness as a way to save and prolong the lives of people – especially the ones she cares about the most. My daughter graciously agreed for me to interview her about cervical cancer, and in this article, I’m sharing what I learned.

Precancerous Cells

In the above paragraph, I mentioned precancerous cells found in my middle daughter’s abnormal pap test results. I have a precancerous condition, too, and I’ve had it for several years. Mine, however, has nothing to do with the cervix. I have MGUS, which is often a precursor for multiple myeloma, a blood cancer. My favorite aunt died from multiple myeloma, so Melissa has been very concerned about my precancerous cells. I’ve often wondered if that was one reason for her pursuit in a degree in cancer registry.

What are precancerous cells? Precancerous cells are abnormal cells that suggest the possible development of a cancerous condition. If you have such cells, it doesn’t mean that you have cancer, nor does it mean that you will develop cancer. It means that the cells need monitoring closely, as they might lead to cancer. Precancerous cells are not invasive, and they don’t spread. Abnormal cells can be caused by inflammation and infections, and when those conditions are resolved, the abnormal cells often are, too.

It’s much better to find precancerous conditions than it is to find cancerous conditions. At least the cells haven’t developed into cancer yet, and they might not ever do so. If you have abnormal cells that make your physician suspicious, he or she will monitor you on a regular basis. That should give you some peace of mind. If and when changes for the worst occur, your doctor will be on top of it.

What Is Cervical Cancer

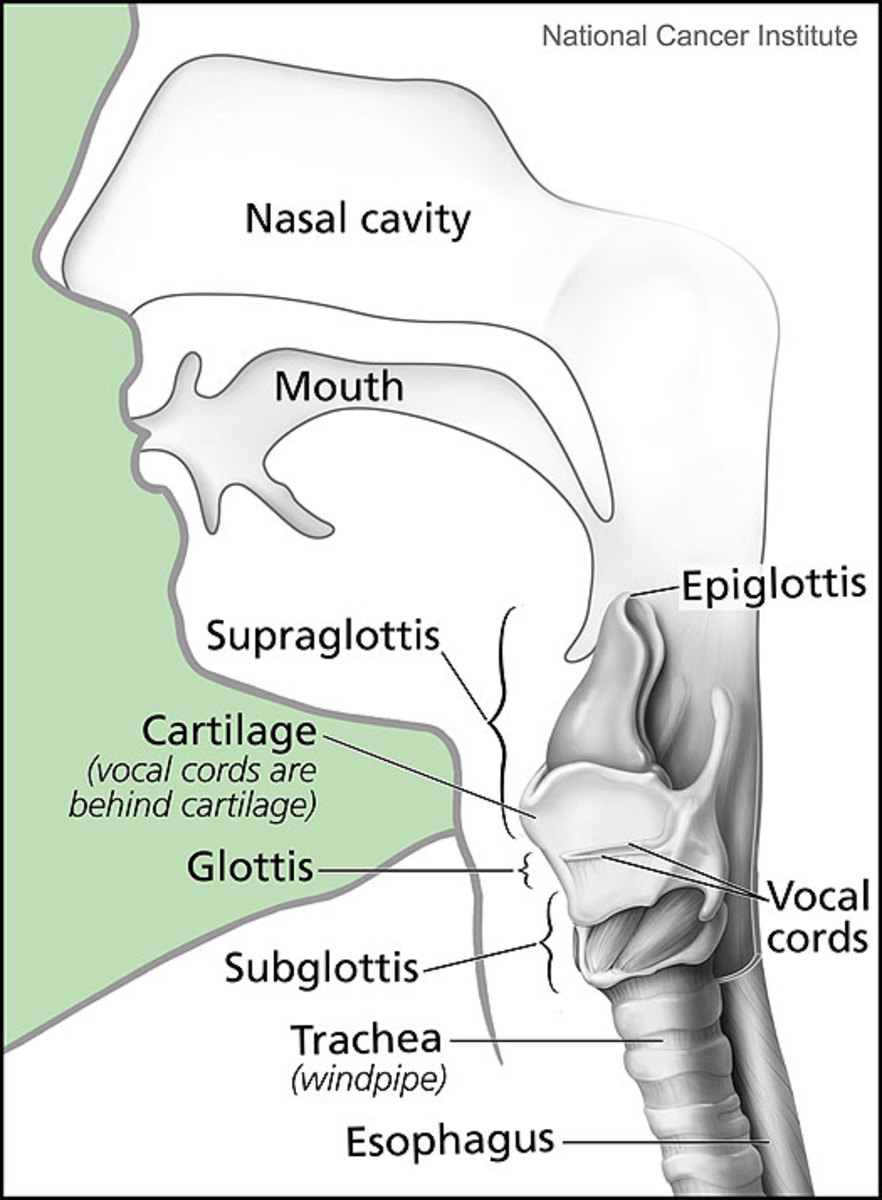

Cervical Cancer is cancer of the cervix, obviously. The cervix is the slender neck that joins the uterus and the vagina. The cervix has four parts. At the top is the internal os, the tiny opening that leads into the uterus. Beneath the internal os is the endocervical canal, which connects the uterus to the external os. The external os is the opening into the ectocervix, the part that projects into the vaginal wall. Think of the cervix as sort of a tunnel that’s slightly conical in shape. It has several purposes. It provides a way for menstrual blood to leave the uterus, and it provides a way for sperm to travel from the vagina into the uterus. It also plays an important role in pregnancy. While the fetus is developing, the cervix remains closed, but it relaxes during labor so that the baby can be born.

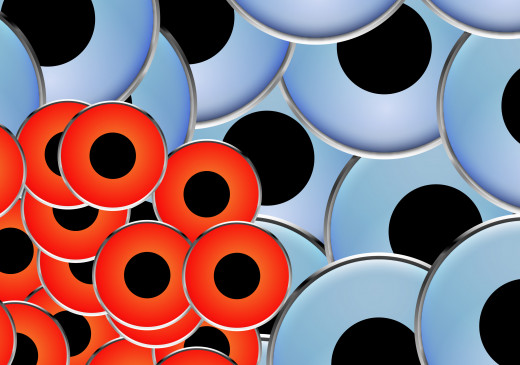

Cervical cancer occurs when something goes wrong with the natural life cycle of cells. It’s normal for our bodies to make new cells when we need them, but sometimes new cells are created when they’re not needed. These abnormal cells can crowd out normal, healthy cells. This type of cancer starts on the surface of the cervix, but if not treated, the cancerous cells can spread to deeper parts of the cervix and can spread to other organs and tissues.

The American Cancer Society predicts that more than 12,000 cases of cervical cancer will be diagnosed in 2012, along with over 4,000 deaths caused by the disease. Those are some alarming figures, but fortunately, deaths from the cancer have been decreasing since the mid 1950s, thanks to cancer awareness and cancer screening.

What Is Cervical Cancer:

Causes Of Cervical Cancer

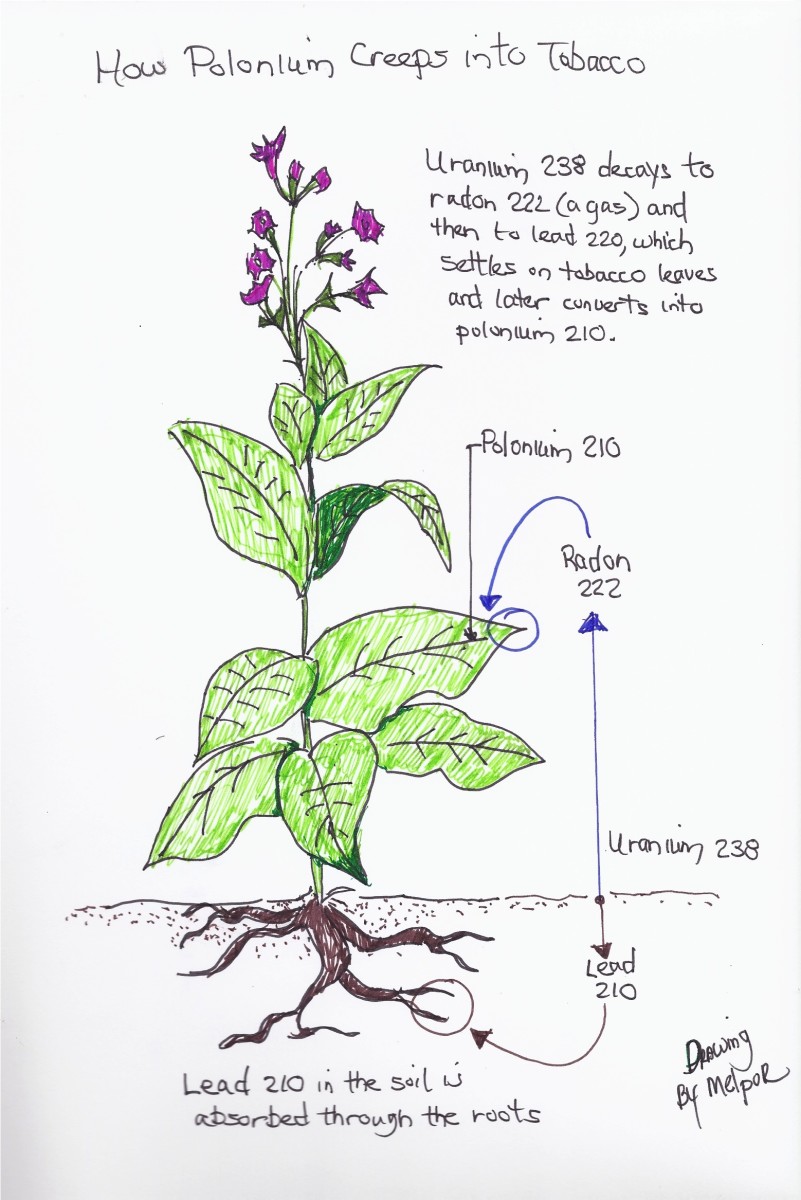

Among the causes of cervical cancer, the chief culprit is human papillomavirus, commonly referred to as HPV virus. Most people don’t realize this, but there’s more than just one HPV virus. In fact, there are over 150 viruses that fall into this category, and chances are that you’ve had one of these viruses at some point in your life – if you’ve been engaging in sexual relationships, although you might not have even been aware of the infection.

How is it that some women who are exposed to the HPV virus have few or any effects, while for others, the virus leads to cancer? That partly depends on which type of HPV you have, but it might also depend on other factors. Females with weak immune systems are more likely to develop cervical cancer, as are those who smoke, have been under extreme stress, have other sexually transmitted diseases, or have been on birth control pills for a long time. Genetics might also play a role. Women who have given birth to more than three children via vaginal delivery are also at higher risk.

Causes Of Cervical Cancer:

What Is HPV

As I’ve already mentioned, HPV stands for human papillomavirus and there are some 150 different strains that are closely related. Of all these different viruses, about a third are spread by sexual contact, including oral, vaginal, and anal sex. Some of the HPV virus types are more dangerous than others. The less dangerous forms can cause genital warts or no symptoms at all, while the high risk types can cause cancer. And it’s not just cervical cancer they can cause, either. They can also cause cancer of the vulva, the penis, the anus, and the throat.

What Is HPV:

Cervical Cancer Symptoms

The symptoms of cervical cancer might go unnoticed at first. They include irregular bleeding or spotting between periods, unusual discharge, pain in the pelvic region, and painful intercourse. A change in the menstrual cycle can also be one of the first cervical cancer symptoms, along with unusually heavy periods. If you’ve already gone through menopause but begin bleeding again, that could be a sign, too.

I’ve already explained that cancer begins as cellular changes. When the cells on the surface of your cervix begin to change, you probably won’t experience any symptoms. By the time you do experience some noticeable symptoms, the cellular changes might have already developed into cancer. That’s why regular cancer screening is so important.

Cancer Diagnosis

When and how is a cancer diagnosis made? For cervical cancer, the first sign of trouble is usually found from cells obtained through a pap test or smear. If your physician finds cells that have undergone abnormal changes, further testing will most likely be done. Your doctor will probably recommend a biopsy. In a biopsy, a small amount of tissue is removed so that it can be studied by a pathologist. Not only is a biopsy an invaluable diagnostic procedure, but it can sometimes serve as treatment for cervical cancer, too. A biopsy might actually remove all the cancerous or precancerous cells present.

There are several different types of biopsies that might be used to make a cervical cancer diagnosis. One type is a cervical conization, which I’ll discuss more later in this article. Another type is the endocervical curettage, in which a medical instrument is used to scrape tissue from the endocervix. A colposcope might also be used to identify abnormal surface tissue of the cervix so that a small section can be removed with forceps.

If cervical cancer is discovered through a biopsy, the physician will order more testing to see if the cancer has spread to other organs and other parts of the body. For example, a cystoscope might be used to examine the urethra and bladder, or you might be put under general anesthesia so that an extensive pelvic exam can be performed. Also, a proctoscope might be used to examine the rectum for cancer.

Furthermore, CT scans, PET scans, MRIs, ultrasounds, and x-rays with and without contrast might be used to determine if the cancer has spread beyond the pelvic region. Areas of the body that might be examined through these methods include the lungs, the liver, the pelvic lymph nodes, the abdominal lymph nodes, and other areas.

Stages Of Cervical Cancer

As with most cancerous conditions, there are different stages of cervical cancer. They depend on how large the cancerous tumor is, on how deeply into the tissue the cancerous cells have invaded, and whether or not the cancer has spread to other parts of the body. Staging is very complicated and detailed, and to make matters more confusing, there are two systems used to describe the stages of cervical cancer. One is the system used by the Federation Internationale de Gynecologie et d’Obstetrique (FIGO), while the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) uses another staging system and classification.

For most patients, the staging system used by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) seems the easiest to understand, although I’m not sure if it’s based on the FIGO or on the AJCC system. The NCI categorizes the stages of cervical cancer in a 0-4 ascending scale, with sub-categories within each major stage. In stage 0, precancerous cells are found deep within the cervical lining. The cells might or might not become cancerous. With stage I, cancer cells are found only in the cervix. If the cancer cells have spread outside the cervix but not into the wall of the pelvis, the cancer is described as stage II. If the cancer is described as stage III, it means it has spread to the pelvic wall, the lower part of the vagina, or has caused kidney damage. With stage IV, the cancerous cells have spread beyond the cervix and into the rectum, the lungs, the liver, the bladder, the bones, the intestines, or to other organs or regions of the body.

Cancer Prevention

Doctors and other health care professionals are learning more and more about cancer prevention, and much of the general population is taking notice. Depending on the type of cancer, preventative measures vary somewhat. For instance, eating a healthy, high fiber diet might help prevent colon cancer, while refraining from smoking helps prevent cancers of the lungs and other organs. Avoiding excessive sunlight helps to prevent skin cancer.

When it comes to cervical cancer prevention, there are several strategies that might prove effective. Obviously, one is to never have sex – in any form. Of course, that’s not very realistic for most adults or for many teens. It’s safer, however, to limit your number of sexual partners in order to reduce your chance of coming in contact with HPV. It also helps to avoid smoking and to keep your immune system as healthy as possible. Regular pap tests are imperative. In the case of abnormal pap tests, your doctor will have the opportunity to carefully follow up on your situation.

HPV Vaccine

The HPV vaccine is one of the most effective preventative measures against cervical cancer. There are two vaccines that protect individuals from the HPV virus – Gardasil and Cervarix. Gardasil can be given to males and females, and it helps protect against several different types of cancers, including penile, vaginal, anal, and vulvar cancers, in addition to protecting against cancer of the cervix. The vaccine also provides protection against genital warts. Gardasil provides protection again HPV virus types 6, 11, 16, and 18. Three injections are administered over a six month period.

Cervarix prevents only cervical cancers, so it’s only given to females. This vaccine is recommended to females aged ten to twenty-five years. It’s injected into the muscle of the upper arm in three doses. The second dose is administered one month after the first dose, and the third and final dose is given five months after the second. Specifically, Cervarix protects against HPV types 16 and 18, and for these two types, the Cervarix vaccine has shown to be more effective than Gardasil.

An HPV vaccine won’t protect against all forms of HPV virus, but it will provide effective protection against the ones most often associated with cervical cancers. Because the vaccines don’t provide 100% protection, regular pap tests and cancer screenings are still important, even for those who have received the cancer prevention treatment.

HPV Vaccine:

Cancer Screening

The most important type of cancer screening for cervical cancer is through a pap test. All females should begin getting regular tests at the age of twenty-one. Through the age of twenty-nine, a pap test should be done every three years. If all the tests have been normal, women should begin getting the tests every five years, beginning at the age of thirty. The cancer screening process should also include testing for HPV virus once the patient has reached the age of thirty. As long as the results have been normal, this schedule should be followed until the patient reaches the age of sixty-five.

Females who have had a hysterectomy that removed both the uterus and the cervix do not need to continue getting cancer screening for cancer of the cervix – unless the surgery was performed in response to cervical cancer or to precancerous cells and tissue. In that case, the doctor will decide how often the patient should be tested.

Women who have high risk factors for cervical cancer will probably need to be screened more often than every three to five years. These factor include but are not limited to having a compromised immune system, extended use of steroids, or exposure to Diethylstilbestrol when they were in the womb. The attending physician will decide how often screenings and tests should be undergone.

If you received the HPV vaccine according to the recommended schedule, you’ll still need to receive pap tests. Remember – the vaccine isn’t 100% effective against all types of the HPV virus.

If you can’t afford cancer screening because you don’t have health insurance coverage, you might qualify for Women’s Heath Medicaid. Also, some communities, including ours, has a special program that provides cancer screening for uninsured women. Ours includes pap tests and breast exams for women between the ages of forty and sixty-five. To help spread cancer awareness among teenagers, we also have a special Teen Health Center that offers education and testing for sexually transmitted diseases, along with treatment. The Center also provides support for young people who wish to abstain from sex.

Pap Test

In a pap test, cells are scraped from the external os with an instrument called a spatula. A brush-like instrument is also used to collect cells from the endocervical canal. The cells obtained are examined through a microscope to discover whether any abnormal of precancerous cells are present, or the cells might be tested in some other way.

If you have an abnormal pap test, it doesn’t mean that you have cancer. It means that the cells found are not dividing normally, or that old cells are not dying the way they normally do. There could be reasons for this other than cancerous conditions. Your doctor will evaluate the cells and decide if treatment is needed. In some cases, your physician might decide to watch the cells to see if they increase in number. If treatment is required, there are basically too methods for getting rid of the abnormal cells – ablation and excision.

With ablation, the abnormal cells are destroyed with a laser or they’re “frozen” with cryosurgery. This method is often used when the risk of cancerous cells is low or when there are only a small number of abnormal cells affecting a small area.

When abnormal tissue in the cervix is examined and the nature of the abnormal cells cannot be determined, excision therapy is often the best choice. Excision involves removing the abnormal tissue. This might be done with laser conization, in which a cone-shaped piece of the cervix is removed by a laser; cold-knife conization, when the same procedure is done with a scalpel; or a loop electrosurgical procedure, where an electrified loop of wire is used to remove tissue. An advantage to excision over ablation is that with the former, the removed tissue can be examined and studied.

Abnormal Pap Test:

Can Cervical Cancer Be Cured

Can cervical cancer be cured? I spoke with the cancer specialists at our local hospital to find out the answer to this question. I was told that the general consensus is that no cancer can really be “cured,” but that it can go into remission. In effect, the best outcome is to have a lifetime remission. I also asked about the removal of the cervix when the cancerous cells were limited to that specific part of the body. Wouldn’t the cancer be cured then? The answer was no, not necessarily. That’s because whatever caused the body to make those abnormal cells can still be present and might show up in another part or region at a later time. Relapse is always a possibility, so it’s important to be vigilant with follow-ups with your oncologist.

Cancer Clinical Trials

You might be interested in becoming a volunteer for cancer clinical trials. Researchers for drug companies are constantly trying out new treatments and drugs for different types of cancers. If become involved with these trials, you’ll get the latest and most cutting edge therapies. To find out about cervical cancer clinical trials in your area and that might be a good “fit” for you, you can visit websites or make phone calls:

Eviti Clinical Trials: 877-227-8451

National Cancer Institute: http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/search

Memorial Sloan-Kettering Current Cancer Clinical Trials: 866-280-0449

City of Hope Cervical Cancer Research and Clinical Trials: http://www.cityofhope.org/patient_care/treatments/cervical-cancer/Pages/cervical-cancer-research-and-clinical-trials.aspx

http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Cancer-of-the-cervix/Pages/clinical-trial.aspx

Cervical Cancer Treatment

Cervical cancer treatment is largely based on the different stages of cervical cancer. For example, in stage 0, the abnormal tissue might be removed or destroyed with cryosurgery, laser surgery, electrosurgical excision, or cervical conization. If the patient doesn’t want to have children in the future, she might receive a hysterectomy.

For patients in stage I, treatment options might include hysterectomy, internal radiation, external radiation, lymph node removal, cervical conization, and/or chemotherapy. Cervical cancer treatment for stage II might involve a combination of external radiation, internal radiation, and chemotherapy. Lymph node removal and a radical hysterectomy might also be performed. Treatments for stage III are the same as those used for stage II cervical cancer – radiation therapy along with chemo. For treatment of cervical cancer in stage IV, radiation therapy and chemotherapy are used. Symptoms of cervical cancer are often treated in order to make the patient more comfortable. Also, some patients are allowed to try new drugs that are still in the testing stage by taking part in clinical trials.