Diabetes Facts: Diet Restrictions and Oral Medicines in Place of Insulin

The first break in the "rigid diet" front came in the 1930's as a result, curiously enough, of the pressure of pediatricians. With insulin already in use more than a decade at that time, pediatricians discovered that diabetic youngsters still did not grow considerably as a result of undernourishment, although they were getting insulin to help them metabolize sugars, they were not being permitted diets to satisfy the caloric demands of growing children. The pediatricians started to exert pressure to better the children's diets, pressing for a more normal caloric intake, the use of insulin, they asserted, had made dietary improvement possible and there was no longer any reason to cling to unnecessary and even grave restrictions.

Under this pressure the diets were changed. Gradually the notion grew and spread that the diabetic— even the adult diabetic—may be permitted to enjoy a more normal nutrition as a consequence of insulin. Today, while the dietary issue has improved substantially, there is still some opposition to change and the tug of war carries on.

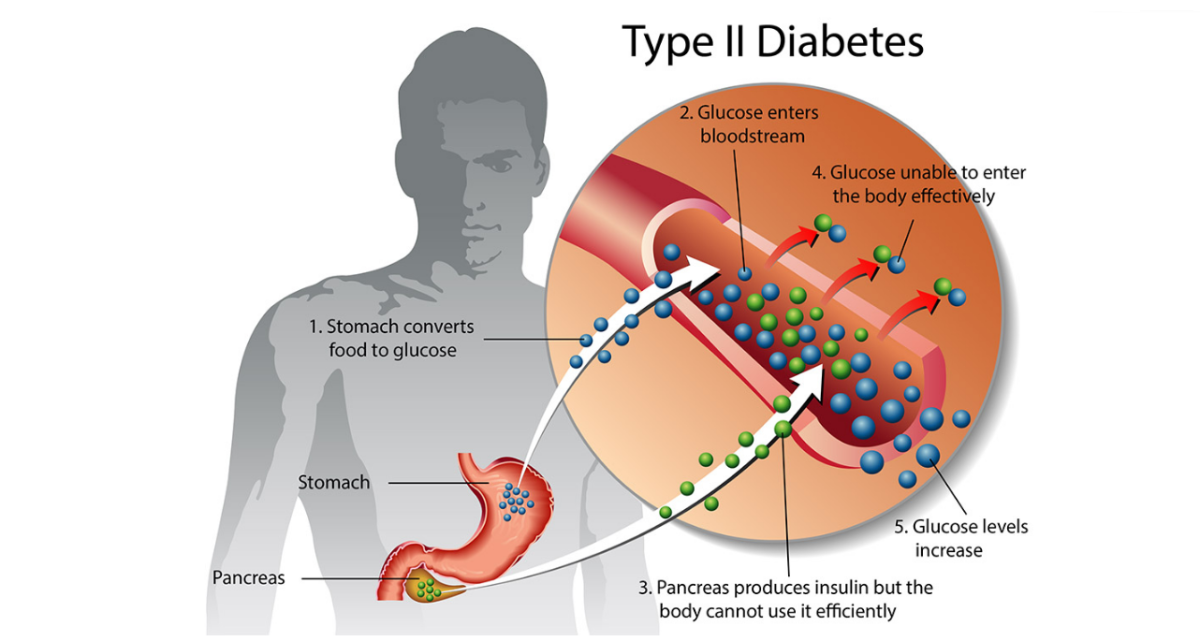

The search for a cure didn't end with insulin's isolation—though the hormone is very effective a treatment at that time, new research lost a good deal of its urgency. But insulin isn't a cure, nor is it the perfect treatment. Some patients reject insulin and need unusually huge amounts. It must be managed carefully and given in precise dosages. Moreover, while it may free the diabetic from the unyielding adherence to a strict diet, it also binds him to the need for day-to-day insulin injections and exposes him to the dangers of insulin shock.

The fact that insulin must be injected has been a chief problem. Since it's a protein substance, it is destructed by the digestive juices and hence can't be taken orally. This produces a number of special problems. The diabetic, apparently, cannot be expected to go to his doctor each day for his injection. Therefore he must give it to himself or have other relative or neighbor give it to him. It is easy to see how the need for insulin injections, apart from being inconvenient, may occasionally become a distinct hardship.

So, from the very instant insulin was discovered, a search was started for a drug which may be taken orally to control diabetes. In June, 1957, after an intensive period of work which had been set into motion as the outcome of a series of medical accidents, the first substance that may be taken orally to reduce blood-sugar was released to doctors in the U.S. This drug, already commonly used in Europe, has the chemical name of tolbutamide and is distributed in this country and Canada as Orinase. In the rest of the world it is called Rastinon.

Although it is an exhaustively tested drug, Orinase has encountered some resistance, as did insulin in its day. Much of this comes up from the fact that the way in which the drug works is not yet known.

Normally, this is a valid scientific reason, since there's always a theory that the unknown may be unsafe. Still, understanding the mode of action of a useful drug isn't always an assurance of safety, nor is lack of understanding needfully a bar to a drug's use. We still don't understand how insulin works, how much of the antibiotics work, or even how aspirin works.

While this oral drug is surely not a cure, it can replace insulin injections in several adult diabetics.