Four Things You Shouldn’t Say to a Grieving Friend (and What to Say Instead)

![Comfort in Grief, Frederick Walker (1840-1875) [PD:1923] Comfort in Grief, Frederick Walker (1840-1875) [PD:1923]](https://usercontent2.hubstatic.com/7559315.jpg)

Grief visits all of us at some point in our lives. We each deal with it in our own way, and, knowing how awful we felt when we last were grieving, it’s only natural that we try to comfort our friends when we see them in pain. At the same time, are uncomfortable around people who are grieving. This discomfort on our part, coupled with the desire to give comfort, often leads well-meaning people to say things that are at best unhelpful, and at worst unwittingly hurtful or insulting, when all we’re trying to do is help our friend feel better. Well, that’s part of the problem: we shouldn’t be trying to help someone who’s grieving to “feel better.” Who are we to dictate how a grieving friend ought to be feeling? We should be offering our support, not trying to change how our friends feel at the moment—even if right now they feel like curling into a ball and sobbing into your shoulder.

Here are some things that you shouldn’t say, why you shouldn’t say them, and some suggestions for what you might want to say or do instead.

Don’t Say: “I Know How You Feel.”

This is a natural thing to say—we are social creatures. We want to belong. That’s why we play team sports or join fraternities and sororities. Or if you’re more of a nerd like me, it’s why you go to science fiction conventions. One of the first things we try to do when making a new friend is to find some common ground—a shared hobby, a shared experience, even something as seemingly trivial as a shared favorite movie or rock band. In an uncomfortable situation, reestablishing this rapport seems like the thing to do: you want to let your friend know that he’s not alone, that you’re right there with him.

Why Not?

Because you don’t. Seriously: you don’t know how he feels. You didn’t just lose your dad to a stroke—your friend did. You can’t possibly know how your friend is feeling if your own dad is still walking and talking. And guess what? Even if your own father passed away only last year to a similar illness, you still don’t know how your friend feels. His relationship with his dad is completely different from your relationship with yours. You don’t know how your friend and his dad related to each other when you weren’t around. Maybe they had a great relationship, the kind you only wish you had with your own dad. Or maybe it’s more complicated than that. Maybe your friend never felt that he lived up to his dad’s expectations. Maybe the last time they talked, your friend told his dad to go take a flying leap. So on top of grieving for his dead father, your friend may also feel relieved that he doesn’t have to deal with the unrealistic expectations anymore, guilty for the way he last spoke to him, and like a horrible person for feeling relief at his dad’s death.

There are all kinds of factors that go into how a person feels at any one time. Even if you know all the details of your friend’s relationship with his dad, there’s no one possible way to feel about it. You don’t know how he feels right now—you can’t possibly. To assume that you do is pretty presumptuous.

Don’t Say: “Is There Anything I Can Do?”

When someone’s hurting, it’s natural to want to offer help. But this isn’t the best way to offer it.

Why Not?

There isn’t anything you can do, and you both know it. Nothing you can say or do will bring the deceased back.

Don’t Say: “It’s All Part Of God’s Plan.”

This is a very common thing to say, and you’d think that it would be a comforting thing to say. It reminds us that there’s a purpose to the universe, that God is looking out for us (or at least paying attention to us), and that we’re all important in our way. Except when it doesn’t.

Why Not?

Well, for one thing, your friend may not share your faith. Unless you’ve talked about religion at length (and unless you’re very close, you probably haven’t), you can’t assume that everyone you know is also [whatever your faith happens to be]. Sure, the US has a pretty big majority of people who are at least nominally Christian, but even assuming that your friend falls into that category, the different denominations’ ideas about whether God takes an active role in Earthly affairs can be pretty far apart. Even if you’re fairly sure that you and your friend are on the same page—you attend the same church, for example—her ideas about theology and doctrine may not match yours as closely as you think. Whether your theologies match or not, nobody wants to hear that her husband died because God wanted him dead. Plus, it implies that you have some insight into what God has planned for us on Earth, which is kind of arrogant. Finally, it can imply that this death is no big deal: it’s just another part of God’s plan.

There is a secular version of this that goes like so: “Everything happens for a reason.” This is also not something a grieving person wants to hear. “Oh, my husband is dead, my kids have lost their dad, but that’s okay: it happened for a reason!?”

Don’t Say: “She’s In A Better Place.”

Most of the world’s major religions include an idea of an afterlife in which the worthy are rewarded and the unworthy are punished. You’d think saying something like this would at least send the message that you thought highly of the deceased, and that you’re confident that they’ll be going to the afterlife where virtuous people go.

Why Not?

Regardless of whether your friend shares your faith (see above), unless you are the acknowledged leader of your shared religion, you do not get to decide who does and doesn’t go to Heaven. Further, as awesome as Heaven may be, it also would have been pretty nice if the deceased had been able to stick around long enough to get married, graduate from college, get her drivers’ license, or take her first steps. Basically, you’re telling your friend that his daughter’s death is a good thing, when you think about it. Even if your friend believes his daughter went to Heaven when she died, now probably isn’t the right time to imply that going to Heaven as a child is better than getting to grow up on Earth.

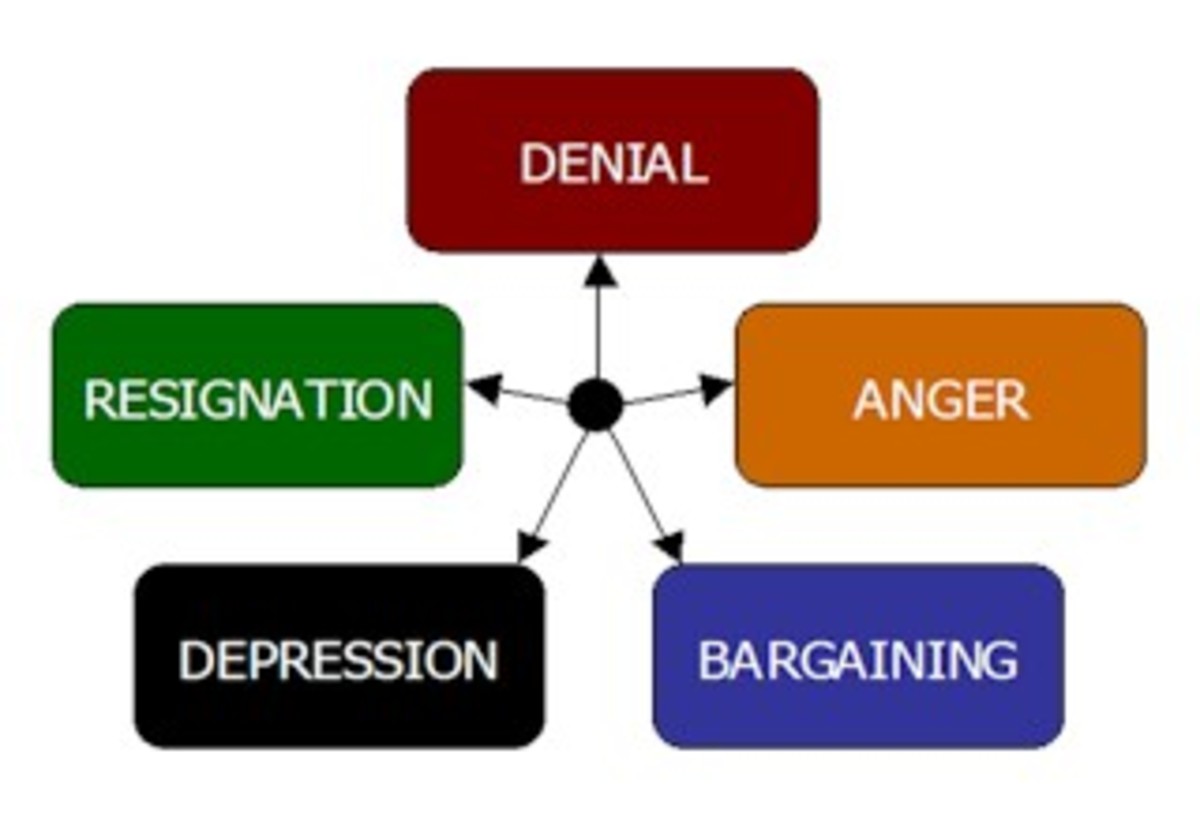

What About The Five Stages of Grief?

A lot of folks like to point at the Kübler-Ross Stages of Grief (Denial, Anger, Bargaining, Depression, Acceptance) as a road map to feeling better. The problem with this is that even Dr. Kübler-Ross points out that the list is not necessarily complete, not everybody goes through all the stages, and they don’t always occur in the same order. These stages of grief are not—and were never meant to be—a checklist for what one needs to go through to get on with their lives. Rather, it’s a kind of tool for people who aren’t grieving, one that can help us to understand what our friends might be going through, and help us to be patient with them while they come to terms with their loss.

The important thing to ask about a grieving friend isn’t which stage of grief they’re on at the moment, but rather: Are they functioning? Are they going to work, getting the dishes done, showering, getting the kids off to school, etc?

If their lives are more or less going on, it doesn’t really matter if, weeks later, they suddenly need a tissue in the middle of a shopping trip. Grief doesn’t come with an expiration date. But if your friend hasn’t showered in days and has no clean clothing to change into, you might want to talk to his family about looking in on him regularly, and perhaps seeking the advice of a grief counselor.

What You Should Say Instead

So far we’ve focused on what not to say. As promised, here’s some suggestions for what you ought to say instead:

Start With This:

“I’m so sorry for your loss; it must be very difficult for you.”

And then shut up and listen. Your friend may need to talk. They may need to cry. They may need to cry so much that they get snot and/or makeup all over your suit. Or they may just need to sit and pray. Or sit and think. Or just sit. Whatever it is your friend needs to do, let them do it.

Follow Up With This:

“Have you eaten lately?”

Sometimes when people are grieving, they forget to take care of themselves. They might go longer than they ought to without having something to eat and drink, which is no help to anyone, especially someone going through emotional turmoil. If your friend hasn’t had anything to eat in a while, bring them something. It doesn’t have to be much—and probably shouldn’t be. A small plate of cheese and crackers will do, with maybe a cup of coffee or a glass of water to wash it down. Of course, take your friend’s dietary needs into account: don’t bring cheese to someone who’s lactose intolerant, for example, or a ham sandwich to a vegetarian.

Then See About This:

If you know that there’s something that your friend needs doing—for example, the lawn needs to be mown—then do it. But don’t show up at your friend’s place and ask where his lawnmower is. Bring your own equipment and do the job without bothering your friend. Depending on the season, you could rake your friend’s leaves, or shovel his snow. Maybe you could drop off a ready-to-cook lasagna. If you’re close enough and have the time, you could volunteer to watch the kids while your friend meets with attorneys or does whatever legal things she needs to do. The point is, don’t make an empty offer that you both know will never be taken up. If you really want to help, then just go ahead and help. But don’t ‘help’ in such a way as to make extra demands on your friend’s time or attention—that’s the opposite of what you want to do.

If you want to offer real help, but you aren’t close enough to know that your friend will welcome your assistance, make a specific offer. Say something like, “I know you’re dealing with a lot right now. I’ve got a lasagna made up in the fridge. Can I bring it by for you and your family tomorrow? All you need to do is put it in the oven for forty-five minutes.” If your friend refuses the offer, be gracious about it—he’s not obligated to eat your lasagna. If your friend accepts, then follow through: bring the lasagna, and do not expect to be invited to stay.

Finally, leave the remarks about God, the afterlife, reasons, plans, and the like for your friend’s religious leader. Most people take great comfort from their faith, but now is probably not the time for you to bring it up, especially if you aren’t part of the same religious community. If your friend brings it up, do not take the opportunity to proselytize, however gently. (This goes for non-religious folks, too!) Do not contradict your friend’s ideas about what the afterlife might be like. Whether your friend says the departed is “at peace” or “watching over us” or “with God” or “awaiting reincarnation” or “reveling with the Aesir in Valhalla,” no matter what your friend may have to say about it, just keep your opinions to yourself and be supportive.

Grief, like love, is not a one-size-fits-all emotion. It’s complicated. It can be scary, draining, and exhausting, and there’s no right way to experience it. Don’t try to help a grieving friend feel better. That’s probably not something you can do in any case. All you can do is help your friend get through it to the other side, however long it takes.

Fred Schade, MSW contributed to this article.