Non-Emergency Medical Transportation

Medical Transportation Organizations

According to Vince D. Robbins (2005), author of “A History of Emergency Medical Services & Medical Transportation Systems in America”, defines medical transportation as:

“the movement of patients to, from, or between medical facilities of any kind, including physicians’’ offices, ambulatory care centers, specialized medical facilities, such as dialysis centers, and hospitals. It usually concerns patients who are not experiencing emergent medical conditions, although not always. Some individuals requiring transport to a higher level of definitive medical care, may be moved from one hospital to another, tertiary care hospital and may be in critical and/or unstable state” (p. 3)

According to Vince D. Robbins (2005), author of “A History of Emergency Medical Services & Medical Transportation Systems in America”, defines medical transportation as:

The history of medical transportation systems (MTS) can be traced back to Native American societies who used horse drawn/dog drawn “stretchers” (travois); Indian societies who used covered stretchers (dhoolies) to transport the ill/deceased; Egyptian societies who used camel stretchers (panniers); and 15th Century Spanish societies who developed mobile field hospitals in times of war (ambulancia) (Robbins, 2005, p. 7).

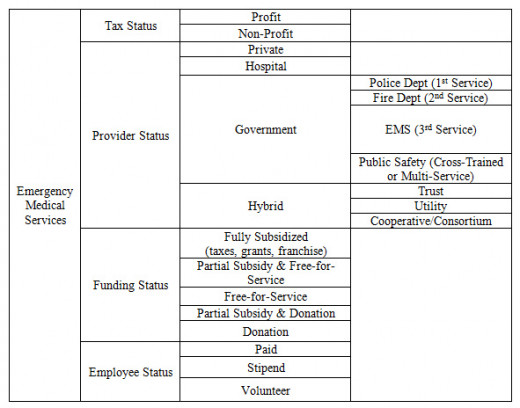

The history of medical transportation systems in America begins in the colonial period. At this point in history, America was far behind Europe in terms of medicine and medical transportation. The colonies were made of smaller, tight knit, undeveloped societies, and in these societies medical treatment was handled by the neighborhood. The beginning of the development of emergency medical services (EMS) and transportation in America was the American Revolution. During this time Americans realized (2) things: (1) the need for rapid medical assistance; and (2) the need to categorized patients by level of medical need/urgency. Between the American Revolution and the Civil War the Continental Army and its Hospital Department were disbanded and the development of EMS and MTS in the United States halted. The Civil War is when EMS and MTS were exceedingly developed. The Union Medical Department used horse drawn wagons, as ambulances, and set up (3) different types of triage locations: (1) “Field Dressing Station” – located on/near the battlefield, primary triage location; (2) “Field Hospital” – located within a short distance of the battlefield, secondary triage location where patients were categorized properly according to conditions; and (3) “General Hospital” – located far beyond battlefields in low key/ easily accessible locations, patients, such as post surgery cases, were sent here for further or extended care. After the war, many hospitals maintained ambulatory services for the public. In 1890, the first-civilian manufactured ambulance was created by Hess in Ohio; it was horse drawn. In 1910, the first known attempt at an aircraft ambulance was built in North Carolina and tested in Florida, but it failed. In the 1920s and 1930s volunteer emergency medical squads sprang up all over the country. The American Red Cross (ARC) established nearly 900 Emergency First Aid Stations by 1936, and by 1939 there were nearly 5,000 stationary and mobile units across the United States. However during World War II posts were severely understaffed because those who were trained medically were sent overseas. World War II and the Korean Conflict brought about medical advances concerning trauma within the military context that spilled over into the civilian sector, including the use of helicopters as emergency medical transportation units, and the advance of on-scene medical treatment, “such as intravenous fluids, by non-physicians, [which] marked a milestone in the progression of clinical care” (Robbins, 2005, p. 20). In the 1960s, an increase of motor vehicle accidents called for an increase of EMS. Accident Death and Disability: The Neglected Disease of Modern Society by the National Academy of Sciences and A Mobile Intensive Care Unit in the Management of Myocardial Infarction by J. Frank Pantridge and John S. Geddes called for efficient pre-hospital EMS for trauma and cardiac crises. In the 1970s, EMS was a fully recognized branch of the medical infrastructure of the United States, from then on it evolved into a sophisticated industry of its own. Today EMS can be classified using the following chart:

There are several different types of human service professionals who work within the medical transportation system. These professionals can be categorized according to training. First responders include police officers and firefighters with first aid training, they are typically able to stabilize situations in preparation for EMTs. There are three levels of EMT: EMT-B/D (Emergency Medical Technician – Basic or Defibrillator), EMT I/85 (Emergency Medical Technician – Intermediate), EMT I/99 (Emergency Medical Technician – Intermediate/ Advanced), and EMT-P (Paramedic), Specialty Care Transport Paramedics, and Nurses.

After performing an informal search for medical transportation companies in the state of New Jersey, YellowPages produced over 500 results, from A & A Medical Transport to Z Best Ambulance Corp. According to Kimberly Palmer, author of “Paramedic” within the Best Health Care Jobs of U.S. News:

“an increasing call volume due to the country’s aging population is expected to keep job prospects high for EMTs and paramedics. The Bureau of Labor Statistics projects EMT and paramedic employment growth of 23.1 percent between 2012 and 2022, adding 55,300 more professionals to the field” (par. 2)

The baby boomer generation is doing a lot to fuel this profession, hence the need for private medical transportation, as opposed to emergency medical transportation. Regardless of the demand for this highly trained emergency medical personnel, pay isn’t the best in this field.

Palmer reports:

“the median annual salary for EMTs and paramedics was $31,020 in 2012. The best-paid 10 percent in the profession made approximately $53,550, while the lowest-earning 10 percent made approximately $20,180. The highest-paid in the profession work in the metropolitan areas of Tacoma, Wash., San Francisco, Calif., and Olympia, Wash.”

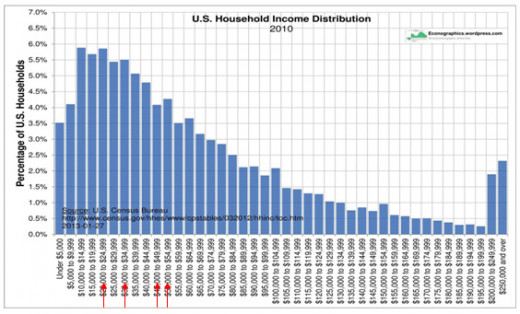

According to Rick Suttle, author of “The Average Income for a Non-Emergency Medical Transport Company” the answer is: “$46,000 as of 2013” for the company owner (para. 2). With those numbers in mind, let’s consider the following graph by the U.S. Census Bureau (2010):

These four arrows represent the four estimated annual incomes of EMTs, Paramedics and Medical Transportation company owners by Palmer and Suttle. As we can see, these important members of our society do not rank very high in the American class system – one of the problems I noticed about this system. When speaking with a paid EMT he said other problems include lack of uniformity considering hiring standards, and not being formally trained to deal with resistant clients, especially those who are being forced to go unwillingly.

As with any profession or career concerning emergency or non-emergency medical situations has to consider cultural differences. For example, some religious women do not want to be medically cared for by a man, because they consider it inappropriate. According to the Florida Medicaid Non-Emergency Transportation Provider Handbook section on Provider Guidelines under the Cultural and Linguistic Competency sub-header:

“CDT’s [Commission for the Transportation Disadvantaged] goal is to provide effective transportation services to people of all cultures, races, ethnic backgrounds, and religions in a manner that recognizes, values, affirms, and respects the worth of the individual Medicaid beneficiaries, protects and preserves the dignity of each Medicaid beneficiary and recognizes and addresses the individual’s cultural diversity. In order to fulfill this goal, CTD has a cultural competency plan which serves as its guide for interaction and communication with Medicaid beneficiaries.

STPs [Subcontracted Transportation Provider] should also implement a cultural competency plan that describes how it will ensure that NET [non-emergency transportation] services are provided in a culturally competent manner to all Medicaid beneficiaries, including those with limited English proficiency. The cultural competency plan must describe how the STP, transportation operators and employees will provide effective transportation services to people of all cultures, races, ethnic backgrounds, and religions in a manner that recognizes values, affirms and respects the worth of the individual Medicaid beneficiaries and protects and preserves the dignity of each Medicaid beneficiary.

STPs must also make its cultural competency plans, and any updates, available to all staff, providers and subcontractors (if applicable). The cultural competency plan must also be made available to beneficiaries upon request, at no cost” (p. 17)

When speaking with members of this profession, though, most of the problems are company and/or location specific.

If you were unable to get around on your own, but had constant and specific medical needs what would be your first pick?

References

Anonymous Medex Employee. (2014, March 9). [E-mail interview by the author].

Florida Commission for the Transportation Disadvantaged. (2011). Cultural and linguistic competency [Provider Guidelines]. In Florida Medicaid non-emergency transportation provider handbook (pp. 17-18).

Palmer, K. (n.d.). Paramedic. US News, Best Health Care Jobs. Retrieved from http://money.usnews.com/careers/best-jobs/emergency-medical-technician-and-paramedic

Robbins, V. D. (2005, March). A history of emergency medical services & medical transportation systems in America [PDF]. Retrieved from https://www.monoc.org/bod/docs/history%20american%20ems-mts.pdf

Stuttle, R. (n.d.). The average income for a non-emergency medical transport company. Retrieved February 21, 2014, from Global Post website: http://everydaylife.globalpost.com/average-income-nonemergency-medical-transport-company-33135.html