Prevention of stroke in patients of atrial fibrillation

According to WHO statistics, the global incidence of atrial fibrillation occurs in 0.5% of the population, which is steadily increasing all over the world likely to assume the status of an epidemic shortly. With the rising incidence of atrial fibrillation, the incidence of stoke in patients suffering from AF is also rising. Atrial fibrillation has widely been accepted as a cause of embolic stroke. Depending on other risk factors, the incidence of stroke in persons with AF is as high as 18% per year.

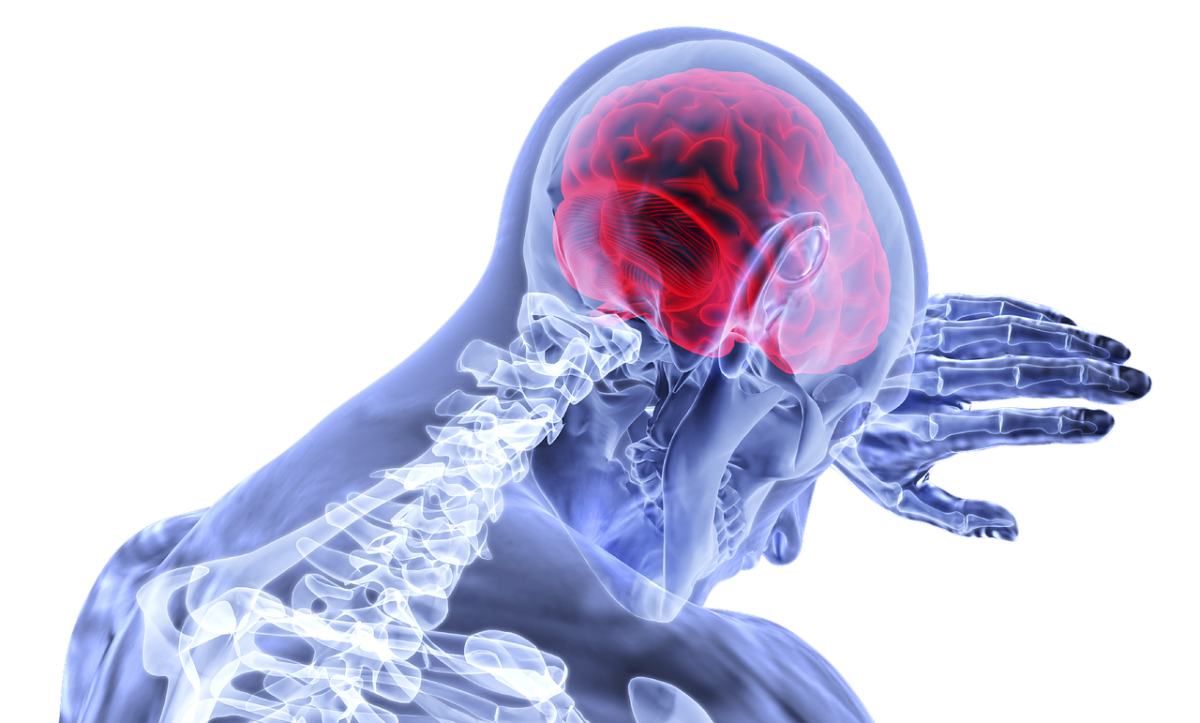

Embolic stroke – Stroke is the most feared and, unfortunately, the common major complication of atrial fibrillation.

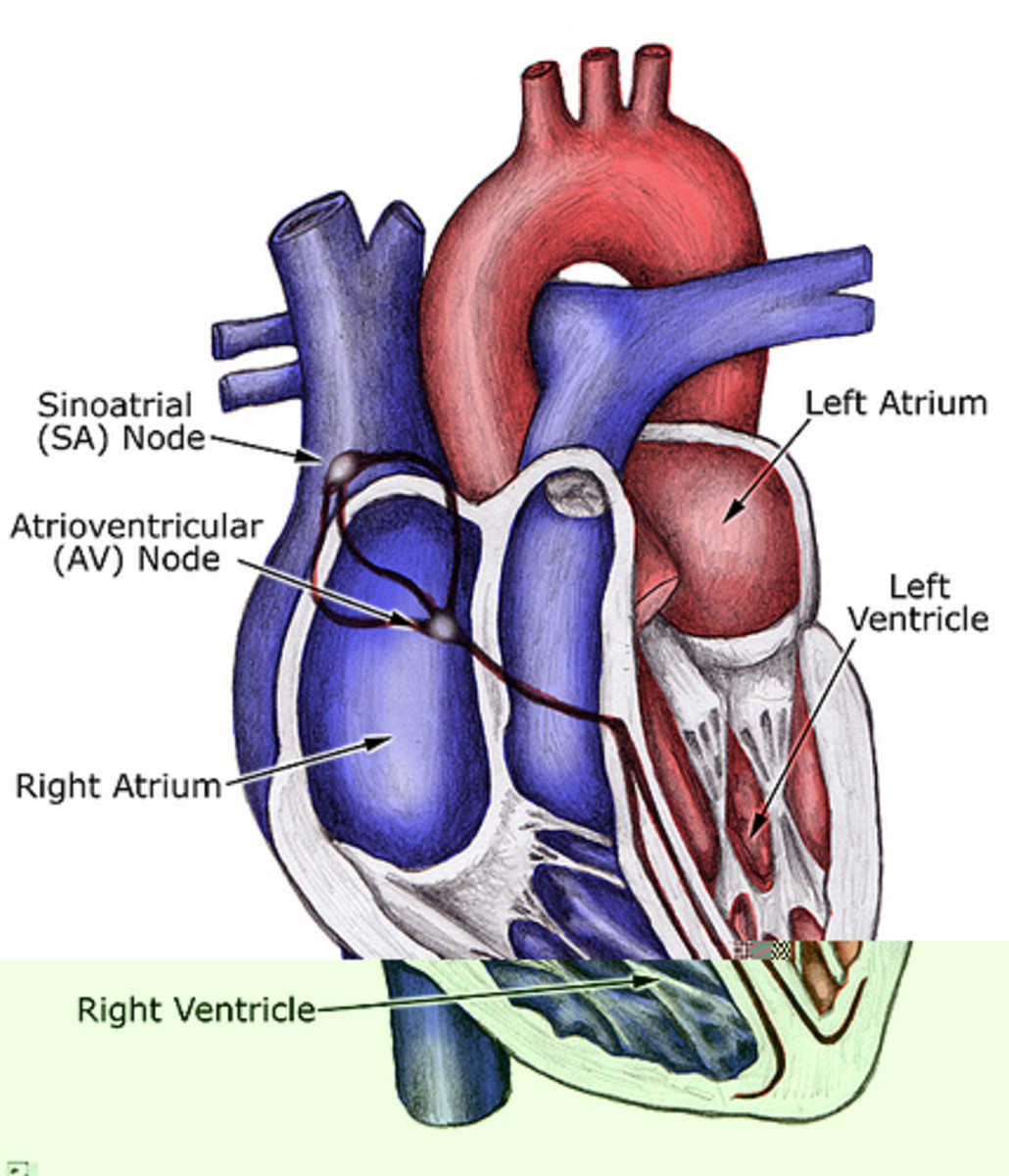

In atrial fibrillation the heats’ electrical impulse doesn’t begin in the SA node situated in the right atrium. Instead it begins in another part of the atria or in the nearby pulmonary veins. The signals spread erratically throughout the atria causing it to fibrillate. The atria and ventricles no longer beat in a synchronized way. The ventricle may beat at a rate of 100 to 175 times a minute in contrast to the normal rate of 60 to 100 beats a minute. As a result, the blood isn’t pumped into the ventricles as well as it should be. This causes the stasis of the blood in the atria resulting in the formation of blood clots. If these blood clots break loose and travel to the brain in the form of emboli, an embolic stroke most likely occurs.

All cases of AF are not chronic but many episodes may occur only sporadically and infrequently for a shorter period of time. This is called paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Surprisingly, some cases of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation may go unnoticed because of lack of symptoms. Such patients are said to have silent or occult atrial fibrillation, which mostly poses a diagnostic challenge to the doctors.

Prevention of stroke -

To prevent the occurrence of stroke the patient has to manage AF effectively with the help of one’s cardiologist. The effective management, which depends on the type of AF, the duration of the condition and any other underlying medical condition, involves the following –

- Treating the heart rhythm to make it regular

- Treating heart rate to slow it down

- Using anti-coagulants

Treating the heart rhythm - To treat the heart rhythm anti-arrhythmic drug is prescribed. These drugs help the heart to beat more regularly. Your doctor will advise, which drug is more suitable because different types of drugs work differently.

If the drugs fail to restore the rhythm to normal, cardioversion is employed to restore the rhythm. Cardioversion uses a brief electrical shock with or without medicine to help the heart to return to its normal rhythm. It is more likely to work if AF had not been there for long. However, there is a risk that AF may return.

Treating the heart rate – If the heart rhythm is not controlled by medications or cardioversion, medications to control heart rate are used. The heart rate will be reduced though the rhythm is irregular. This causes the heart to work more effectively. There are several types of medications and your doctor will decide which the right one is for you. Inform your doctor if there are any side-effects. The patient should have a regular check-up for blood pressure and heart rate.

Anti-coagulants – This group of drugs increases time it takes for blood to form a clot. By taking an anti-coagulant, the blood is less likely to clot and so the risk of stroke is reduced. There are many types of anti-coagulant drugs. Your doctor will take a decision which one to use. The dose of these drugs has to be tailor made as they are likely to cause unwanted bleeding if given in higher doses than required. The patient using anti-coagulant drugs will have to attend anti-coagulant clinic for blood tests every 6 to 8 weeks.

The CHADS2 scale – The risk of stroke in patients having AF is usually assessed using a score technique called CHADS2. It is used to determine whether or not treatment is required with anti-coagulant or anti-platelet therapy. A high CHADS2 score corresponds to a greater risk of stroke, while a low CHADS2 score correspond to a lower risk of stroke. The CHADS2 score is simple and its usefulness has been validated by many studies. The following table represents the CHADS2 score -

Condition

| Points

| |

|---|---|---|

C

| Congestive heart failure

| 1

|

H

| Hypertension-BP consistently more than 140/90 mmHg

| 1

|

A

| Age equal to or more than 75 years

| 1

|

D

| Diabetes mellitus

| !

|

S2

| Prior stroke or transient ischemic attack

| 2

|

The CHA2DS2-VASc scale - The CHADS 2 score doesn’t include some common stroke risk factors. Therefore, to complement it some additional stroke risk factors have been included in a new score called the CHA2DS2-VASc score. These additional non-major stroke risk factors include age 65-74, female gender and vascular disease. In the CHA2DS2-VASc score, 'age 75 and above' also has extra weight, with 2 points. The following table represents the CHA2DS2-VASc score –

Condition

| Points

| |

|---|---|---|

C

| Congestive heart failure

| 1

|

H

| Hypertension

| 1

|

A2

| Age equal to or more than 75 years

| 2

|

D

| Diabetes mellitus

| 1

|

S2

| Prior stroke or transient ischemic attack

| 2

|

V

| Vascular disease

| 1

|

A

| Age 65 to 75 years

| 1

|

Sc

| Female sex

| 1

|

According to the CHADS2 or CHA2DS2-VASc score, the anti-coagulant treatment is instituted depending on the risk as shown in the following table –

Score

| Risk

| Anticoagulant therapy

|

|---|---|---|

0

| Low

| None or aspirin

|

1

| Moderate

| Oral anticoagulant drugs including new ones or well controlled warfarin

|

2 or greater

| High

| Oral anticoagulant drugs including new ones or well controlled warfarin

|

The above scores are helpful in instituting treatment for patients with AF in clinical practice but they have their own limitations. The limitations of the CHADS2 scale have been removed to some extent in the CHA2DS2-VASc scale. Apart from avoiding stroke in patients with AF, it is also important to minimize the potential adverse effects of treatment with clinical expertise depending on patient’s circumstances.