Singing an Operatic Performance... With Laryngitis. A True "How To".

A Nightmare Turned Into A Victory!

This was the worst case scenario for any musician: I was two weeks away from a full scale operatic recital I had booked, rehearsed for, and advertised. There was to be a full audience, including fellow local musicians whom I respected highly. I had planned the entire recital in full, opting for some of my showiest pieces (I am a high coloratura soprano and had rep consisting of the Queen of the Night, from Mozart's Magic Flute, and Zerbinetta from Strauss' Ariadne auf Naxos. Usually fun, invigorating sings for me, when my voice complies.)

But I had no voice. I was recovering from about 6 weeks of Mononucleosis, within that time I had lost a ton of energy, some weight, and my voice (almost completely). I'd never lost my voice for an extended period of time before, but it was as if every inch of me was swollen. I did everything I knew to do - removed alcohol and caffeine from my life entirely and drank tons of water. Got excess amounts of sleep. Warmed up and stretched and carefully coaxed my voice into resonance, but the best I could do - even the night before the recital - was sing through my middle voice. I had nothing above a high C. All that came out was a terrifying squeak.

But, there were no other sopranos to do this gig and I did not want to do MORE damage to my vocal chords by taking medicine to remove the swelling. So, I came up with a plan B I've never thought of before, and it was wildly successful:

Before I go into these, one important note: I saw two doctors about this condition before performing, and had the green light that there was no vocal damage causing the problems and that I could go ahead with the performance. If battling laryngitis or any other voice-related problems, DO see your doctor before giving a performance. It's too risky otherwise, and you can cause severe damage to your vocal chords if you ignore the problem.

1. New Program. I hated doing this, because I knew the program had been sent out prior to the gig. But I'm not a violinist (anymore). My voice IS my instrument, and it was not in the right shape to sing The Revenge Aria. However, I was finding that singing arias in my lower range - and I had several of those committed to memory - was fine. I removed any aria that was too vocally taxing (coloratura) or above a certain part of my range, and replaced them with lower, slower, calmer arias. We made an announcement right at the start that I would be doing this, and the audience was, thankfully, gracious.

2. Breaks and Intermissions. I will say I was lucky with this one, because there were already a few breaks put in the program where other instrumentalists - a percussionist and a Mezzo Soprano - were performing. But I added more for my accompanist, and he was happy to perform some of his piano solos. Additionally, I took nearly 20 minutes halfway to go in the back and hum/ warm up again and check to make sure my voice felt okay. Since I was singing in the warm/ middle part of my voice, once I relaxed more and realized I would have enough to get me through the performance without harming anything I felt okay. The audience also was able to mingle and get drinks during these breaks.

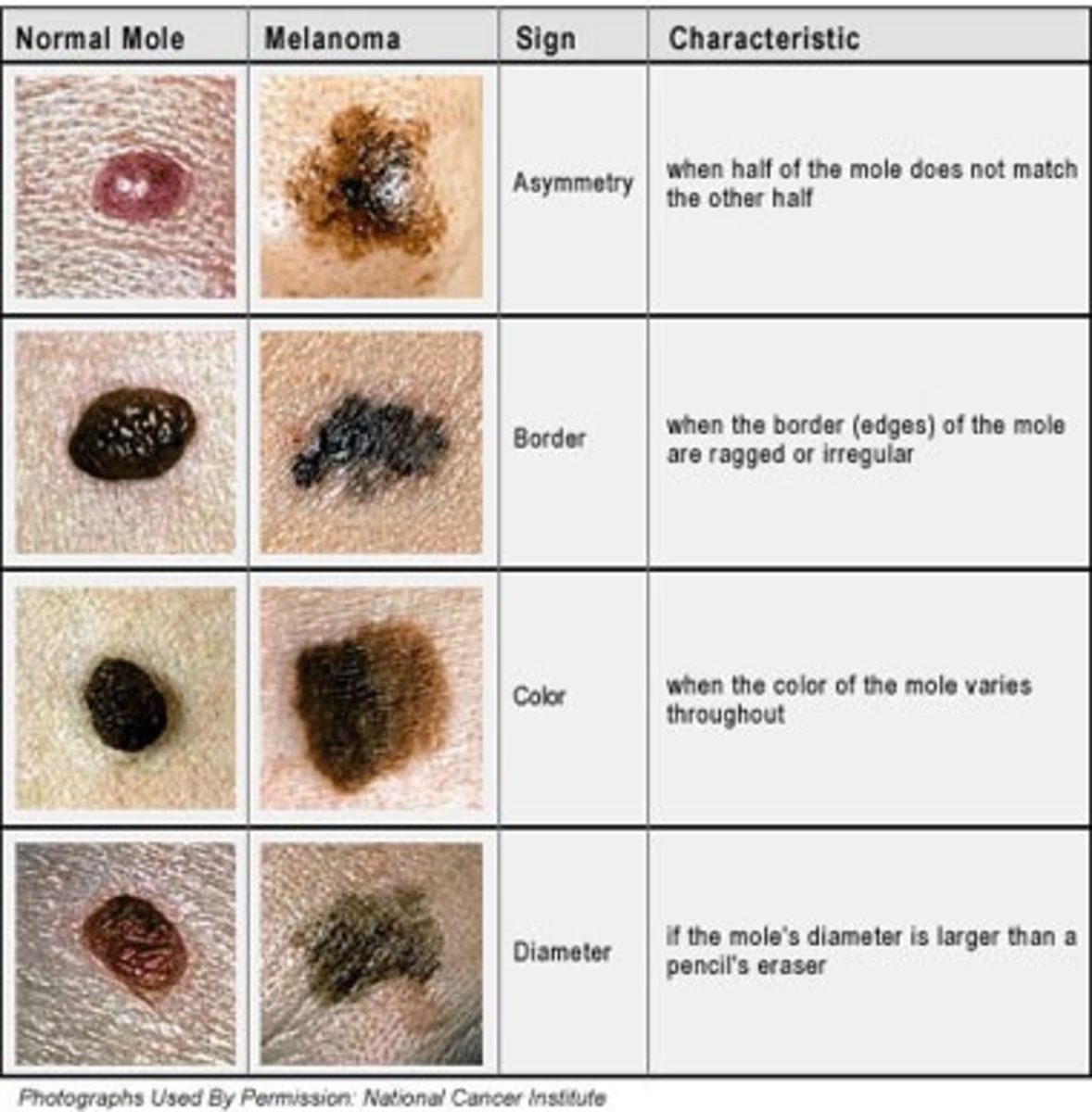

3. Never Stop Hydrating. This really helped for AFTER the recital, because I felt like the muscles had all been warmed up/ kept warm by the gentler singing, and the constant drinking water and coconut water backstage helped further the healing process in the days following. Psychologically, too, knowing I was taking good care of my voice in spite of being in the spotlight for two hours made me feel stronger.

4. Focus On Text. Recitals are typically intimate gatherings, and this was very much the case for me in spite of the physical obstacles and the size of the crowd. Before each aria, we explained what it was about, and then - even if I was technically 'marking' with my voice - the focus on each word of text made the performance more multi-dimensional. I felt like I was able to connect with the audience much more through the words, even if part of my voice was weaker. I felt like I could act the characters more, and I used the space to move around and emote and gesture. It's never JUST about the voice, and I needed to be reminded of that. The weaker instrument actually made me bring out my acting and physical body much much more, and this helped the performance over all.

5. Be Honest. I did not pretend that this was the best shape my voice had ever been in. I walked in and owned the fact that I'd been recovering for a long time, but was given the green light to still do this performance, and was going to have to carry it out the best way I could. I had already given the director all of the information in case canceling was a better option, and he did not want that - so this was what we were left with as a team to carry out the performance. In a way, admitting this to everyone took the pressure off, and I was much less nervous than I normally would be. At that point, there was no more I could do, and in the end everyone seemed happy with the final product.

Live performance is a scary beast. Anything can go wrong: You can trip. Forget Words. Get lost on the way to the venue. Part of the reason people still line up to see performers do their thing live is because of the high stakes of it. We are all human - no one is immune. But there are always ways to share your art without being miserable in the case of an illness or injury, within reason.

Coconut Water Goodness