Maternal Diet, Environment, or Genetics and the Role They Play: Understanding Atopic Disease

Genetics or maternal diet & environment that decides?

It is a known fact that a mother’s nutritional status and habits can have huge implications on the development of the child she is carrying. What she eats or doesn’t eat, can prevent or cause the child to have a disease or birth defect. Although atopic diseases are not currently curable, I believe we can and should focus on prevention through prenatal nutrition while also being aware of the environmental factors.

There have been many discoveries made in the genetics and “environmental” links that play a role in the increased risk for atopic diseases in children. There can be a genetic predisposition. However, it appears that what the mother is exposed to environmentally and her nutritional choices at different points in the pregnancy have a much stronger impact. With our knowledge of the immune system development between mother and child growing rapidly, it is likely that interventions that promote a maternal healthy gut/immune system factor will later lend itself to prevention of atopic diseases in the infant.

The immune system and atopic disease. Epidemic?

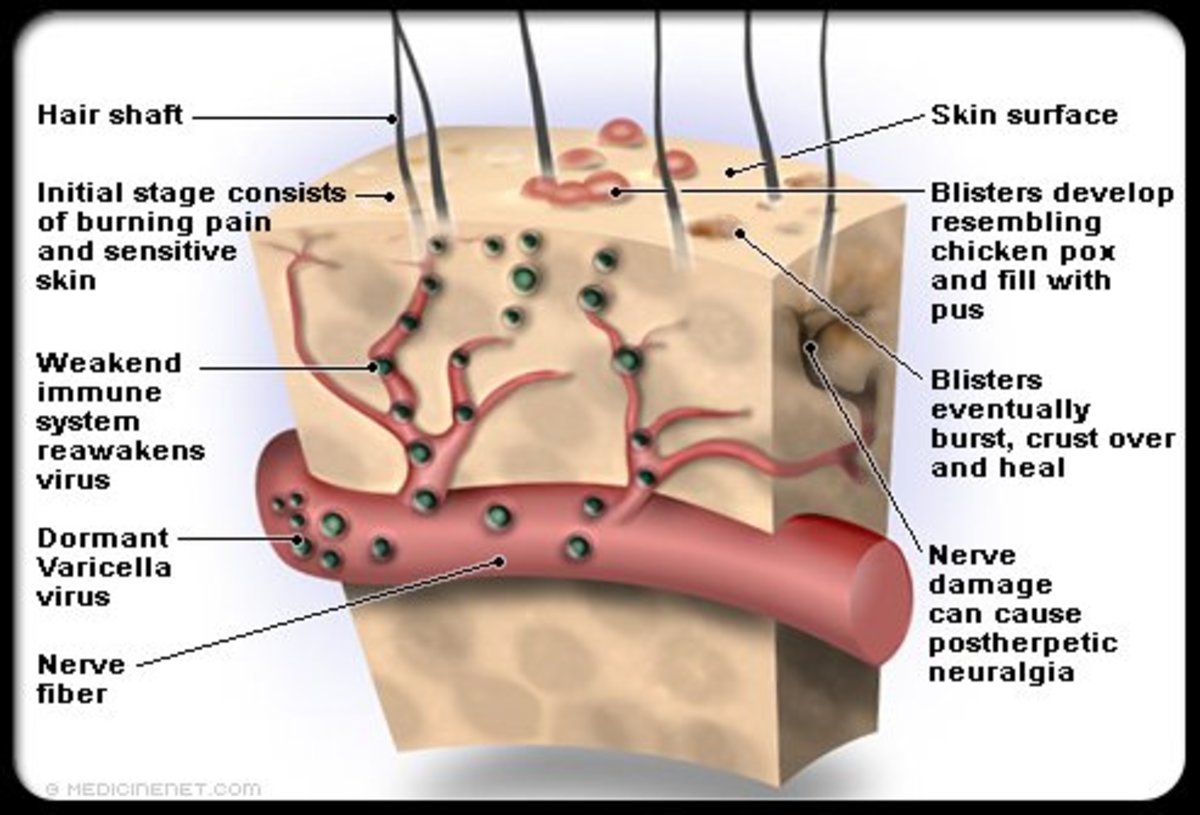

There are 3 immune system diseases that fall under the category of “Atopic Disease”- hay fever, asthma, and eczema. Eczema alone, has 6 different types with “Atopic Dermatitis” (AD) being the most common skin disease worldwide, with early onset eczema affecting up to 30 % of children. Furthermore, if the infant is diagnosed with AD their risk for being diagnosed with the other 2 listed disease increases dramatically and is known as the “Atopic March” or trifecta. (Ziyab, et al. 2017) According to the National Eczema Association “The development of atopic dermatitis in children is influenced by genetics, though the exact way it passes from parents to children is unknown. If one parent has atopic dermatitis, or any of the other atopic diseases (asthma, hay fever), the chances are about 50% that the child will have one or more of the diseases. If both parents are atopic, chances are even greater that their child will have it. However, the connection is not an absolute one because as many as 30% of the affected patients have no family members with any of these allergic disorders.” Atopic dermatitis (eczema) affects approx. 1/5th of all people during their lifetime, but the prevalence varies greatly throughout different areas of the world. In many of the industrialized countries, the prevalence increased so much between 1950 and 2000, that many now refer to it as the “allergic epidemic.”

The science of genetics, research, and outcome.

Clearly, the importance lies in the avoidance of environmental causes as much as possible and focusing on nutritional health as well. The Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) has identified common genetic variants predisposing infants to AD through the mother. But they only account for a very small percentage leading me to believe that prenatal nutrition and environment has more influence than genetics in AD outcome for the infant. Strictly speaking about the environmental implications for exposure and risk, there are two specific papers (1 study, 1 hypothesis) that looked at the causes and environmental factors to the respiratory allergy/disease – one through the initial birth and latex/chemical exposure (Worth,1999) and the other through dust mites and such that the mother may have passed - “Although allergens were not detected in all cord blood samples, a high percentage of them (95%) were positive for specific IgM to both mites in cord blood samples, suggesting that neonates can be exposed and sensitized to airborne allergens during pregnancy.” (Macchiaverni, et al. 2015) There are other studies that have looked at the ability to pass allergies or antigens and protection from mother to baby through placenta, etc. and they have also found that if the mother is exposed to farm life and animals and the family has a dog, it is said to lower the risk of AD in the infant. They have found this via cord blood and the IgE responses, and then furthering the protection is when the child is breast-fed in the early months of life, continuing the transfer of immunities. (Macchiaverni, et al. 2015) Perhaps the most telling information has come from the study of mutations in the filaggrin gene (FLG) which is a skin-barrier gene, the mutations do not always cross to through to the child but do influence the risk of AD through “feto-maternal immune cross talk”. (Esparza-Gordillo, et al. 2015) The importance of the maternal immune status during pregnancy and the important role played by control and awareness of these risk factors is shown many times over and while we cannot currently control the genetic risks for AD we can absolutely focus on reducing other risk factors and triggers via nutrition and environment awareness and interventions.

Gut health and immune system

What we know about the gut health connection to our immune systems is now paving the way for discovery into the origination and power it has between mother and offspring. The low diversity of gut bacteria in the infant can be directly related to AD and even further related to the mother’s gut bacteria/health, even the manner of birth. If the baby is born via C-section, they do not receive the needed bacteria from the mother on their way into the world. (Abrahamsson, et al. 2012) In a double-blind trial, they showed that the administration of the probiotics to women for only 4 months significantly reduced the cumulative incidence of AD among their children at 2 years of age. These were specific strains and used for only 4 months and it cut the rate by 50%. Yet, in a previous study probiotic administration had previously been disregarded, and they now know it is strain specific. I imagine that a longer time frame and a wider range of bacteria would even further prevent incidences of AD. (Lee & Tee 2010) In the “Human Gut Colonization May Be Initiated In Utero By Distinct Microbial Communities In The Placenta and Amniotic Fluid” they offer a lot of hypothesis and ground work findings in this area. It is thought to be the first such study of its kind! They state, “Given our data suggesting that the impact of colostrum microbes on gut colonization is more evident later in the first week of life and the fact that meconium is formed during fetal life, it is perhaps more likely that meconium and colostrum microbiota share a common maternal source than that colostrum directly contributes to the meconium microbiota.” (Collado, et al. 2016) Although much research is still needed, this is an amazing start and goes to show the undeniable link to mother’s influence and offspring’s immune system.

We now know the improvement of gut health, therefore immune system of mom through the addition of probiotics during pregnancy, has shown to prevent AD in the infant after birth, so we can go a step further by also altering the diet to include more of the “allergen” type foods to further fight the onset of AD, since avoiding them seems to do more harm than good. When the mother eats things or does not, it can determine the outcome for the child in many ways. Higher intake of milk and peanuts during the first trimester reduced the odds of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and peanut allergies. Wheat in higher intake during the 2nd trimester was attributed to reduced AD. Again, they specifically state that the link between the development of the infant’s immune system and the mother’s diet/nutritional choices are directly related. (Bunyavanich, et al. 2014) Prior studies that were published also investigated the link of PUFAs and the effect of them in the maternal diet on the fetus, finding that the balance between 3 and 6 can provide protection to the infant and decrease the risk factors for AD. (Calvani, et al. 2006) Higher intake of margarine, vegetable oils (esp. deep fried), had a higher rate of Eczema diagnosed where higher intakes of healthy PUFA’s from fish and such were attributed to higher protection and less instances of Eczema diagnosed. (Stefanie, et al. 2007) They are considering many different effects of many different diets and environmental factors and continue to make links, the immune tolerance of the child later in life has its roots built during prenatal nutritional care. Nutrition plays as much if not greater a part in the prevention of immune diseases and birth defect as environment or genetics. (Loo, et al. 2017)

Flaws to the research?

I have noticed that some of the newer studies are now finding errors in previous studies done. One in particular had said that cows-milk and exposure that the farm children had actually increased the risk, but now they are finding it was in the boiling of it not the actual milk and again in the different strains of probiotics. I believe we will find more of these types of changes as we dig deeper and learn more. A concern I have is that many of these studies touch on the role that antibiotics and other allopathic interventions (c-sections, vaccines, etc.) have on these immune system outcomes. I find that none of them list actual vaccination status (there was one that said it was on the questionnaire but never mentioned anything after) – which also happens to lend to the environmental impact of the child and mothers health with their adjuvants, antibiotic content, and other various toxins that intrude on the immune system and its function. The only paper I found this far that does reference the connection is a recent paper written by Thomas A.E. Platts-Mills, MD, PhD, FRS called “The Allergy Epidemics: 1870–2010”. I would encourage you to read this as it explains many links through the years.

Some final thoughts

So, while genetics clearly has its own role to play and our environmental exposures do as well, it does go to show, that in the end nutrition – whether actual food/dietary intake or supplements like vitamins or probiotics boosting our immune system, do have huge a impact on the outcome of these immune system defects and diseases. We may not be able to completely avoid or prevent these diseases while pregnant, but we can absolutely take huge steps to reduce the risks with nutrition. We must be mindful and diligent to provide focused education to mothers about the importance of a balanced whole-food, nutrient rich diet during pregnancy in order to counter the possible negative outcomes. Teaching mothers-to-be about some of the dangers in everyday products and their natural substitutes can be a huge step in the right direction when working to prevent Atopic diseases, and even when having to treat them.

Where to find the research:

References:

Ziyab, A. H., et al. “Expression of the Filaggrin Gene in Umbilical Cord Blood Predicts Eczema Risk in Infancy: A Birth Cohort Study.” Clinical & Experimental Allergy, vol. 47, no. 9, 2017, pp. 1185–1192., doi:10.1111/cea.12956.

Worth, Jennifer. “Neo-Natal Sensitization to Latex: A Medical Hypothesis.” Journal of Nutritional & Environmental Medicine, vol. 9, no. 4, 1999, pp. 305–312., doi:10.1080/13590849961528.

Macchiaverni, Patricia, et al. “Early Exposure to Respiratory Allergens by Placental Transfer and Breastfeeding.” Plos One, vol. 10, no. 9, 23 Sept. 2015, pp. 1–14., doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0139064.

Esparza-Gordillo, Jorge, et al. “Maternal Filaggrin Mutations Increase the Risk of Atopic Dermatitis in Children: An Effect Independent of Mutation Inheritance.” PLOS Genetics, vol. 11, no. 3, 2015, doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005076.

Abrahamsson, Thomas R., et al. “Low Diversity of the Gut Microbiota in Infants with Atopic Eczema.” Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, vol. 129, no. 2, 2012, doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2011.10.025.

Lee, Joyce, and Shang Ian Tee. “ Probiotics in Pregnant Women to Prevent Allergic Disease: a Randomized, Double-Blind Trial.” F1000 - Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature, vol. 163, no. 3, 22 May 2010, pp. 616–623., doi:10.3410/f.5718956.5700064.

Collado, Maria Carmen, et al. “Human Gut Colonisation May Be Initiated in Utero by Distinct Microbial Communities in the Placenta and Amniotic Fluid.” Scientific Reports, vol. 6, no. 1, 2016, doi:10.1038/srep23129.

Bunyavanich, Supinda, et al. “Peanut, Milk, and Wheat Intake During Pregnancy Is Associated With Reduced Allergy and Asthma In Children.” Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, vol. 133, no. 2, 10 Feb. 2014, pp. 1373–1382., doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.12.717.

Calvani, Mauro, et al. “Consumption of Fish, Butter and Margarine during Pregnancy and Development of Allergic Sensitizations in the Offspring: Role of Maternal Atopy.” Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, vol. 17, no. 2, 2006, pp. 94–102., doi:10.1111/j.1399-3038.2005.00367.x.

Stefanie, et al. “Maternal Diet during Pregnancy in Relation to Eczema and Allergic Sensitization in the Offspring at 2 y of Age.” OUP Academic, Oxford University Press, 1 Feb. 2007, academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/85/2/530/4649545

Loo, Evelyn Xiu Ling, et al. “Effect of Maternal Dietary Patterns during Pregnancy on Self-Reported Allergic Diseases in the First 3 Years of Life: Results from the GUSTO Study.” International Archives of Allergy and Immunology, vol. 173, no. 2, 2017, pp. 105–113., doi:10.1159/000475497.

“Eczema Prevalence, Quality of Life and Economic Impact.” National Eczema Association, nationaleczema.org/research/eczema-facts/.

2002-2019

Platts-Mills, Thomas A E. “The allergy epidemics: 1870-2010.” The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology vol. 136,1 (2015): 3-13. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.03.048

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and does not substitute for diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, prescription, and/or dietary advice from a licensed health professional. Drugs, supplements, and natural remedies may have dangerous side effects. If pregnant or nursing, consult with a qualified provider on an individual basis. Seek immediate help if you are experiencing a medical emergency.