Why Sexual Abuse Survivors Find It Difficult to Forget: New Studies on How the Brain Stores Traumatic Memories

By Gloria Siess, {"Garnetbird"}

"I have this friend," a lady once said to me, "Who was sexually abused as a little boy, and tied down. He is bi-polar, depressed, and can't even wear a seat belt when he drives. Why can't he just forget all that negative stuff and move on with his life?"

This amazing conversation took place in a small auto dealership in a sleepy mountain town. The woman who asked me this question was not being cold or uncaring--she simply could not understand why her friend would find it so hard to let go of the past. To many incest survivors--myself included-the simple cliche advice to "get moving on with your life," has all the charm of a funeral song. Many do not accept the fact that childhood sexual abuse causes actual brain alterations and damage (See Dr. Bremners work at Yale). Now more research has come forth to indicate that traumatic memories are stored differently and with more intensity than so called normal ones.

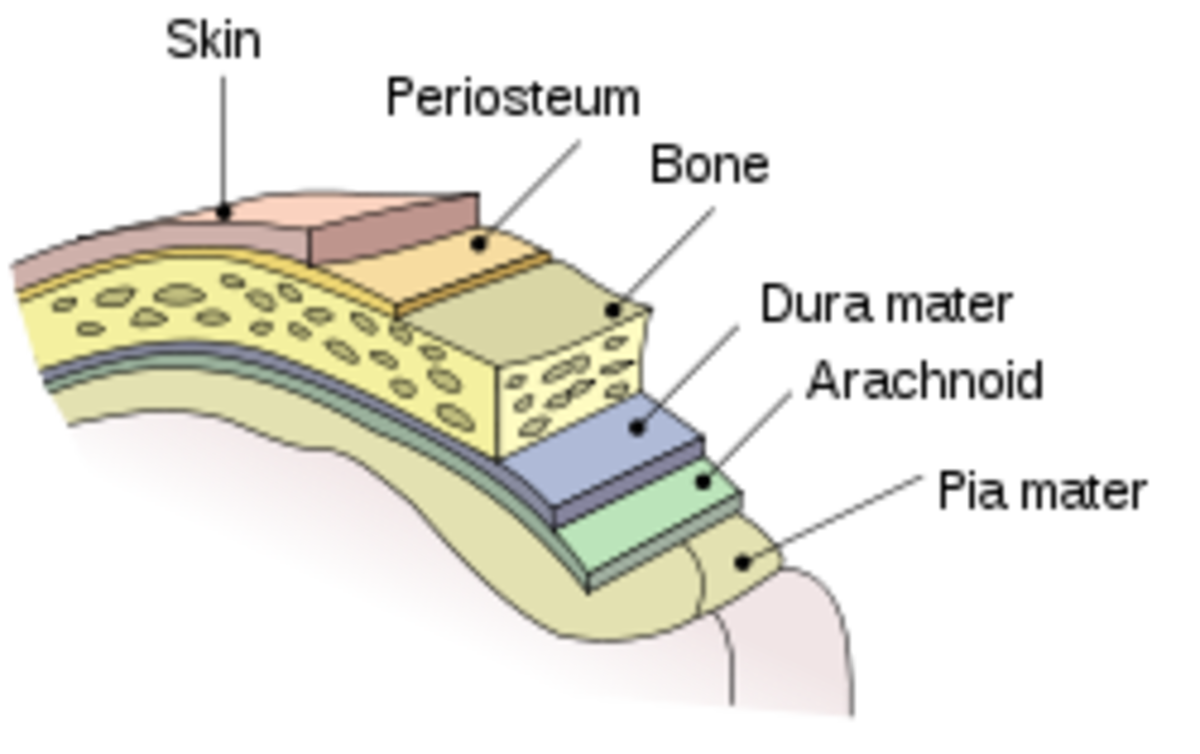

According to Dr. Carvers' article on Emotional Memory Management, traumatic memories take up more space in the brain, and take more time to process. The longer and more severe the abuse, the more storage space in the brain gets activated. Good memories do not carry with them the intense emotions of negative experiences, demanding less attention in the mysterious world of the brain. To put it simply, the more horrific the memory, the more intense the emotions, the more space in your mental file cabinet is utilized. Unimportant memories, such as how many times you turn on the television in the course of a day, are usually dumped by the brain within five days.

Rape, murder and incest, have powerful emotions associated with the events. These type of experiences actually release chemicals into the brain itself. When triggered, the mind will pull up the incest experience from its "file," flooding the survivor with dreadful recall. There are specific therapies for this, but the purpose of this article is not to offer solutions. It is to comfort survivors who have been called weak and self-pitying when they simply could not forget and carry on as though nothing at all had happened to them.