Yellow Baby: A Case of Cytomegalovirus Infection with Biliary Atresia

Infants are commonly afflicted by many medical conditions given the common notion of their frailty, underdevelopment, and lack of resistance to infection. However, one of the most common types of disease processes present in this age group that is not commonly seen in young children, adolescents, and adults are hereditary and congenital malformations! In this review, a case of an infant is analyzed, diagnosed and reported.

The Yellow Baby

We are presented a case of a four-month old infant male who presented in the emergency department with signs of difficulty of breathing. At initial inspection, the patient has slightly labored breathing, reported decreased appetite by his parents, and general appearance of being ill. This was the first time that the patient was seen by a physician, however they reported that the patient had several bouts of being “yellow” even when he was still only several weeks old. They reported the presence of yellow skin and yellow discoloration of the eyes.

The patient stayed in the hospital, and was eventually diagnosed to have an infection of cytomegalovirus (CMV) and what’s more interesting was another finding of biliary atresia! Are these conditions simply two separate entities, in a stroke of luck just randomly affected our young patient? Or is there a possible causal (or even just an association) between those two?

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Infection

Cytomegalovirus is a type of virus which may affect any patient across any age group, this may present with a variety of signs and symptoms. Some people may be affected but may remain asymptomatic. However, it should be noted that pregnant parents may affect their child in the womb or may infect them early upon birth.

The most common presenting features (60-80% of the cases) of CMV infection exhibited by the infant was jaundice and hepatomegaly. Jaundice pertains to the “yellow discoloration”, noted in layman’s terms. Hepatomegaly on the other hand, pertains to 1.) ‘hepato-liver; and ‘megaly’- enlargement of; hence, a term used for liver enlargement. Laboratory abnormalities include elevated liver enzyme levels and this also affects products of the liver such as bilirubin leading to its increased level in the blood call- conjugated hyperbilirirubinemia (Hirsch, 2012).

Blueberry Muffin Appearance

Although infants may acquire CMV infection during delivery via passage through an infected birth canal or contact with contaminated maternal secretions like blood, and genital secretions, transmission is extremely unlikely. There is approximately 40% risk of transplacental infection when a pregnant woman contracts the disease during the first half of pregnancy but history shows no pertinent symptoms of the mother during pregnancy. Some pregnant women may be asymptomatic when CMV infection was contracted, but abnormal fetal ultrasound findings would lead to suspicion of the disease, which were not noted in any of the prenatal checkups that the mother claimed to have undergone (Duff, 2010). Also, another common presenting feature not present in the patient was petechiae that presents as "blueberry muffin".

CMV may be transmitted transplacentally even when the mother was infected months or years before conception (Fowler et al., 1992). Once infected, an individual carries the virus for life and persists in host tissues where it usually remains silent. Congenital infection can arise either from the primary infection, which accounts for majority of the clinical diseases of the newborn, or reactivation infection of the mother and also, early pregnancy (Hirsch, 2012)

Neonates shed most of the virus during the first three weeks of life via urine and saliva. During this period, tests for CMV are most accurate. After the shedding period, it would be very difficult to detect CMV presence (Fowler, 2000). The patient was admitted when she was 4 months old, hence lab tests procuring urine may not show the presence of the virus.

Infants who are symptomatic with CMV infection has high predilection of having congenital problems at birth. This may include malformations such as inguinal hernia, high-arched palate, defective enamelization of the deciduous teeth, hydrocephalus, clasp thumb deformity, and clubfoot (Leung & Sauve, 2003). In this case, the patient did not present any of the congenital malformation that usually presents upon birth. The presence of intra-uterine growth retardation, cranial abnormalities, and poor development (Numazaki & Fujikawa, 2004) are other factors which are not seen in the case of the patient. In this case, gross deformities such as these were not seen in the patient.

CMV Lung Infection

Another finding that is associated with cytomegalovirus is the manifestation of pulmonary symptoms. In one study, it was found that the incidence of symptomatic cytomegalovirus infection is similar between term and pre-term infants. However, the incidence of pneumonitis, in particular, is more numerous and more severe in those born pre-term (Nagy, Endreffy, Streitman, Pintér, & Pusztai, 2004). The pulmonary symptoms may manifest also manifest as pulmonary hypertension. Similar to the gross physical deformities, persistence of pulmonary hypertension is usually insidious in onset and has very high fatality rate presenting at the first weeks of life. In two cases reported with pulmonary hypertension with refractory hypoxemia, the infants were unable to sustained early life due to complications of the mounted inflammatory response (Walter-Nicolet, Leblanc, Leruez-Ville, Hubert, & Mitanchez, 2011).

CMV pneumonitis is one possible complication of this infection. Among the complications of the infection, CMV-associated pneumonia is the most serious, being the most difficult to diagnose due to the unclear true pathogenic role of the virus (Boeckh, 2011). It is, however, more common in immunosuppressed individuals and the chance of immunocompetent individuals to acquire CMV-associated pneumonitis is very little (Hirsch, 2012). Meaning, the infection may not present in individuals who have capable immune system, developed enough to fend off the spread of infection. Newborns and Infants on the other hand, are examples of the contrary.

CMV infection usually manifests in immunocompromised individuals (Berardi et al., 2011). As mentioned, the natural history in the progression of the disease is also not parallel with that of CMV as evidenced by the preceding paragraphs. Hence, CMV infection may NOT be solely attributed for the rapid decline of the patient given the lack of signs and symptoms during the early months and the so pulmonary manifestations upon admission may be due to another etiologic agent.

This leads us to the question— why does the patient present with those symptoms which are not very characteristic of a simple CMV infection? Where does the on- and off jaundice come from?

Biliary Atresia

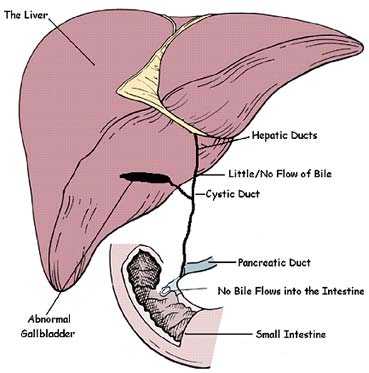

Biliary atresia (BA) is a rare liver disorder commonly seen in young patients, with a diagnosis made within one or two months after birth. For a quick rundown of the disease, here are some pertinent data! In general, it is caused by inability of the ducts and canals of the liver and nearby organs to transmit the products of the liver to the intestines. Furthermore, it causes buildup of the products and wastes inside the liver causing further damage. Biliary atresia may be cause by a variety of factors including an infection, genetic aberration, development problem of the ducts.

A growing body of evidence suggests the development of postnatal extrahepatic biliary atresia due to infection or immune mediated causes. At the time of diagnosis, fibrosis and lymphocytic infiltration is seen on the extrahepatic duct remnant (Sira, et al., 2013; Mack and Sokol, 2005). Antigen-presenting cells play a vital role in the initiation of the immune response. These include macrophages and dendritic cells although endothelial or epithelial cells (including the bile duct epithelium) may also play the role. Meaning that an initial insult caused by a virus or another infection may cause an inflammatory response which then leads to damage in the small ducts in the liver and subsequently its incapacity to maintain its form.

The control of the immune response is a responsibility of regulatory or suppressor T cells. Their objective is to prevent excesses in inflammation and prevent autoreactive T cells. Normally their values increase to adult levels at the first week after birth. Studies showed that there is a deficit in regulatory T cells among patients affected with BA, allowing for exaggerated inflammation leading to bile duct injury. Marked deficits were seen in BA patients who were positive for CMV.

Infection, Inflammation, Fibrosis!

Persistent bile duct injury then leads to further inflammation and fibrosis of the bile duct lumen leading to cholestasis. Cholestatis essentially means retention of the liver products such as enzymes and bile due to the inability to move forward in the channels (Perlmutter & Shepherd, 2002). In essence, they are stuck in the liver and starts to wreak havoc!

There are several inflammatory signals labelled in the next lines which causes this specific damage. It is noted that these signals are amplified when there is an inflammatory reaction or an infection, which in this case is caused by the cytomegalovirus. Cytokines such as IL-18 and TNF alpha also induce liver channels/ ducts changes such as 1) increase in intralobular bile ducts, 2) increase fibrosis of portal spaces and 3) increase in ductules (Hsiao, et al., 2009; Chardot, 2006). All of these foregoing changes lead to the development of perinatal extrahepatic biliary atresia which accounts for the apparent normal appearance of the patient at birth and for the first few weeks of life (Perlmutter & Shepherd, 2002).

The lack of early surgical intervention caused prolonged portal fibrosis which eventually spread to hepatic lobules, thereby causing cirrhotic changes in the liver. This potentially altered hemodynamics (inability to accommodate and adapt to variations in blood flow due to compression of portal veins) in the portal system caused decreased outflow with a subsequent increase in the upstream portal pressure which ultimately produced portal hypertension (Chardot, 2006).

When the atresia is severe, it leads to complete (or almost complete) obstruction of the bile channels and ducts. Ductular obstruction also leads to cholestasis which causes retention of bile components in the liver with eventual entrance to the circulation (Zhou, et al., 2012). Since the liver is still able to conjugate bilirubin but is not able to excrete it, an increase in the amount of direct bilirubin is expected to be seen which accounts for the jaundice (yellow skin) and icteric sclera (yellow eyes) found on physical examination of the patient. Cholestasis also caused the partial or complete absence of bile acid in the duodenum which impaired fat emulsification and later lead to fat malabsorption, which ultimately impaired the absorption of fat soluble vitamins, A, D, E and K (Ramm, et al., 2008; Hsiao, et al., 2009).

Summary

In summary, the patient may have developed biliary atresia due to an acquired CMV infection either when the patient was still in the womb or immediately upon birth. This has caused damage in the ducts of the liver, and eventually progressed to the organ itself hence the manifestations presented by the patient at birth.

References

- Berardi, A., Rossi, C., Fiorini, V., Rivi, C., Vagnarelli, F., Guaraldi, N., … Ferrari, F. (2011). Severe acquired cytomegalovirus infection in a full-term, formula-fed infant: Case Report. BMC Pediatrics, 11(1), 52.

- Boeckh, M. (2011). Complicaions, Diagnosis, Management and Prevenion of CMV Infections: Current and Future. Hematology , 305-09.

- Duff, P. (2010). Diagnosis and Mangement of CMV Infection. Perinatology , 1-6.

- Chardot, C. (2006). Biliary Atresia. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. BioMed Central Ltd: Geneve, Switzerland. DOI:10.1186/1750-1172-1-28.

- Fowler, K. (2000). Congenital Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Infection & Hearing Loss.

- Fowler, K., Stagno, S., Pass, R., & Britt, W. (1992). The Outcme of Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection in Relation to Maternal Antibody Status. The New England Journal of Medicine, 663-667.

- Hirsch, M. (2012). Cytomegalovirus and Human Herpesvirus Types 6,7 and 8. In D. Longo, Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (pp. 1471-1473). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies .

- Hsiao, C.H., et al. (2008). Universal Screening for Biliary Atresia Using an Infant Stool Color Card in Taiwan. Hepatology. Vol. 47, No. 4. Wiley InterScience. DOI 10.1002/hep.22182:.

- Mack, C.L. and Sokol, R.J. (2005). Unraveling the Pathogenesis and Etiology of Biliary Atresia. Pediatric Research. Vol. 57, No. 5, International Pediatric Research Foundation, Inc.: Colorado, USA.

- Leung, A. K. C., & Sauve, R. S. (2003). Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection. Journal of the National Medical Association, 95(3).

- Nagy, A., Endreffy, E., Streitman, K., Pintér, S., & Pusztai, R. (2004). Incidence and outcome of congenital cytomegalovirus infection in selected groups of preterm and full-term neonates under intensive care. In vivo (Athens, Greece), 18(6), 819–23.

- Numazaki, K., & Fujikawa, T. (2004). Chronological changes of incidence and prognosis of children with asymptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection in Sapporo, Japan. BMC Infectious Diseases, 4, 22.

- Perlmutter, D. H., & Silverman, G. a. (2011). Hepatic fibrosis and carcinogenesis in α1-antitrypsin deficiency: a prototype for chronic tissue damage in gain-of-function disorders. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology, 3(3), 1–14. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a005801

- Perlmutter, D.H., & Shepherd, R.W. (2002). Extrahepatic Biliary Atresia: A Disease or a Phenotype?. Hepatology. Vol. 35, No. 6. Wiley InterScience. DOI:10.1053/jhep.2002.34170

- Ramm, G.A., Shepherd, R.W., Hoskins, A.C., Greco, S.A., Ney, A.D., Pereira, T.N., Bridle, K.R., Doecke, J.D., Meikle, P.J., Turlin, B. & Lewindon, P.J. (2009).Fibrogenesis in Pediatric Cholestatic Liver Disease: Role of Taurocholate and Hepatocyte-Derived Monocyte Chemotaxis Protein-1 in Hepatic Stellate Cell Recruitment. Hepatology. Vol. 49, No. 2. Wiley InterScience. DOI 10.1002/hep.22637

- Sira, M.M., Salem, T.A.H., & Sira, A.M. (2013). Biliary Atresia: A Challenging Diagnosis. Global Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. National Liver Institute: Menofiya University, Egypt.

- Soomro, G. et al., (2011). Is there any association of extra hepatic biliary atresia with cytomegalovirus or other infections? J. Pak Med Assoc., 281-283.

- Walter-Nicolet, E., Leblanc, M., Leruez-Ville, M., Hubert, P., & Mitanchez, D. (2011). Congenital cytomegalovirus infection manifesting as neonatal persistent pulmonary hypertension: report of two cases. Pulmonary medicine, 2011, 293285. doi:10.1155/2011/293285

- Zhou K, Lin N, Xiao Y, Wang Y, Wen J, et al. (2012) Elevated Bile Acids in Newborns with Biliary Atresia (BA). PLoS ONE 7(11): e49270. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049270