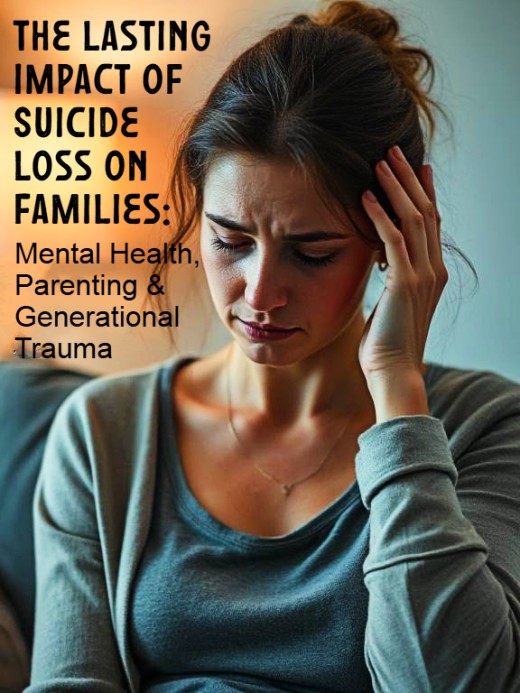

How Suicide Loss Affects Families Across Generations

Suicide in the Family: The Lifelong Effects on Children and Grandchildren

Suicide shattered our family like an earthquake, sudden and devastating. As a teenager, my father lost both his mother and younger brother to suicide just six months apart. Then, in the decades that followed, multiple cousins also died by suicide, each loss widening the cracks in our family foundation. These tragedies left emotional fault lines that continue to ripple through the generations, renewing the fear of suicide with every new crisis and shaping the way we relate to grief, loss, and one another.

Suicide never ends with the person who dies—it reverberates like seismic aftershocks through generations. Its emotional tremors leave a defining and somber thread in the lives of those left behind, shaping their emotional, relational, psychological, and physical development. For children and grandchildren, the loss of a parent or grandparent to death by suicide is not a moment in time but a lifelong inheritance of grief. The fallout touches identity, mental health, career paths, and even one's own personal suicide risk.1

A Wound That Doesn’t Close

Grieving a suicide is unlike any other loss. It’s tangled in trauma, secrecy, and stigma. Survivors are left not only with a gaping absence but also with unanswerable questions: “Why did this happen?” and “Could it have been prevented?” This ambiguity fuels complicated grief, a form of mourning more intense and prolonged than typical bereavement.2

Many survivors experience symptoms of post-traumatic stress, especially if they discovered the death or witnessed its aftermath. Intrusive memories, emotional numbness, and hypervigilance are common. Compared to those who lose loved ones to natural causes, suicide survivors face significantly higher rates of PTSD.3

Children who lose a parent to suicide are more vulnerable to mood disorders, including depression and bipolar disorder, both in childhood and throughout life.4 Early psychiatric symptoms—persistent sadness, panic attacks, impulsivity, substance misuse, and suicidal thoughts—often persist into adulthood, making suicide loss not only a grief experience but also a mental health risk factor.5

Trust, Intimacy, and the Fear of Being Left

Suicide loss reshapes how survivors seek closeness, handle conflict, and navigate intimacy in every relationship that follows, from childhood to old age. Children may experience the death of a parent or grandparent as abandonment, which can evolve into a deep-seated fear of rejection or betrayal.

As a result, adult romantic relationships may be shaped by these fears. Survivors often oscillate between emotional overdependence and mistrust—clinging tightly to partners for fear of losing them or pushing them away to preempt anticipated rejection. Friendships can feel risky too, as many survivors hesitate to share their history, fearing judgment or discomfort. The stigma surrounding suicide compounds this isolation, leaving survivors emotionally stranded when they most need connection.6

These patterns often echo through survivors' parenting, even years later. A parent’s fear of abandonment, for example, can surface as enmeshment—where emotional boundaries blur and family members become overly entangled, thus leaving little room for individual identity. Survivors may become overprotective, struggle with healthy boundaries, or feel haunted by fears of repeating the suicide within their own family. The legacy of parental suicide is not only emotional; it influences how survivors love, trust, and raise their children, creating generational impacts that can last a lifetime.

The Quiet Impact on Work and Achievement

Grief and mental health struggles can impair focus, motivation, and long-term planning. Children who lose a parent to suicide are more likely to face academic challenges, drop out of school, and earn less over their lifetime than their peers.7

In adulthood, survivors may wrestle with career instability or burnout. Some struggle with depression, substance use, or a sense of futility, leading to underachievement or difficulty maintaining employment. Others excel outwardly, driven by an internal pressure to overachieve, prove their worth, or escape their family’s shadow. This push-pull dynamic reflects the complex emotional legacy of suicide loss.8

Psychiatric Risk: Nature, Nurture, and Trauma

Suicide loss increases the risk of psychiatric illness across generations. Children whose parents or grandparents die by suicide are significantly more likely to develop mood disorders, anxiety, and substance abuse issues. In addition, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts are also more common.9

This vulnerability stems from both genetic inheritance and environmental trauma. Suicide often occurs in families with histories of mental illness or addiction, which can be passed down biologically. But the trauma of losing a loved one to suicide adds another layer of risk, making it difficult to separate nature from nurture.10

Trauma That Travels Through Generations

The effects of suicide loss don’t stop with direct survivors. Trauma can be transmitted across generations—even to grandchildren (like myself) who never met the deceased.11 Family silence around suicide deepens this transmission, shaping emotional expression and relational dynamics for decades.12

Children of survivors may inherit both genetic predispositions and the psychological imprint of unresolved grief. A parent’s fear of abandonment, for example, might manifest as enmeshment or difficulty fostering independence. These patterns reinforce cycles of anxiety, insecurity, and emotional fragility.

Dial or text 988 to speak with the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline any time, day or night.

The Lifelong Physical Health Consequences

Survivors of a parent or grandparent’s suicide face elevated long-term health risks, partly due to heightened cortisol levels that impair the body’s stress-response systems. Chronic stress, grief, and trauma during childhood or adolescence can reshape the body in ways that persist throughout life.13

Common physical impacts include:

-

Cardiovascular issues: systemic inflammation, elevated blood pressure, heart disease, stroke

-

Metabolic disorders: obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes

-

Immune dysfunction: frequent infections, slower recovery, autoimmune risk

-

Neuroendocrine disruption: thyroid, adrenal, and hormonal imbalance

-

Musculoskeletal pain: chronic back pain, fibromyalgia, tension headaches

-

Gastrointestinal distress: irritable bowel syndrome, acid reflux, peptic ulcers

Together, these conditions show that suicide bereavement is a whole-person crisis. Children and grandchildren inherit not only grief but also a biological and relational legacy that shapes health, relationships, and life trajectories.

When Suicide Becomes a Family Pattern

Perhaps the most devastating consequence of suicide bereavement is the increased risk of suicide itself. Children of parents who die by suicide are nearly three times more likely to die by suicide and twice as likely to attempt it.

This phenomenon—sometimes called suicide contagion—reflects both inherited vulnerability and the learned perception that suicide is a response to despair. For some survivors, the memory of suicide becomes a haunting presence. During moments of crisis, it can feel like a script waiting to be repeated. Without intervention, the wound becomes a legacy that is replayed across generations.

Breaking the Silence, Interrupting the Cycle

While the impact of suicide loss is profound, it is not inevitable. Survivors who access support—through therapy, peer groups, or community resources—can disrupt the cycle. Family therapy, for example, addresses inherited patterns, helping parents foster healthier relationships with their children.14

Healing doesn’t erase the loss, but it can transform its legacy from pain and silence to resilience and connection. But therapy must be accessed in order to work.

Facts & Statistics About Suicide & Suicide Loss

Grandchildren of suicide decedents may show higher anxiety and attachment insecurity, even if they never knew the deceased

| For every suicide, it’s estimated that 135 people are directly affected, including family, friends, coworkers, neighbors, etc.

|

Survivors are at a 65% higher risk of suicide attempt compared to those bereaved by other causes

| Families with multiple suicides often struggle with a "script of despair", where suicide becomes seen as an option in times of crisis

|

Men are almost four times more likely to actually die by suicide than women, but women are more likely to attempt

| About 1 in 5 people will experience a suicide loss of someone close to them during their lifetime

|

Children who lose a parent to suicide are three times more likely to die by suicide themselves and twice as likely to attempt

| Rural communities have higher suicide rates than urban ones, often due to reduced access to mental health care and greater firearm availability

|

Closing Reflection

The suicide of a parent or grandparent is not a single event—it’s a lifelong inheritance no one wants. Survivors carry a legacy of invisible emotional, relational, and physical scars that shape their mental and physical health, relationships, careers, and sense of self. The impact often reverberates across generations, influencing how families communicate, connect, and cope. Chances are you know someone whose life has been touched by suicide loss.

Suicide is a legacy no one asked for. But within that legacy lies the possibility of change. By naming the pain, challenging the silence, and offering support, survivors can rewrite their family's story. Breaking the cycle begins with breaking the shared silence and building a future rooted in connection rather than despair.

References

1 Jordan, J. R., & McIntosh, J. L. (Eds.). (2011). Grief after suicide: Understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors. Routledge.

2 Mitchell, A. M., Kim, Y., Prigerson, H. G., & Mortimer-Stephens, M. K. (2004). Complicated grief and suicidal ideation in adult survivors of suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 34(4), 385–394.

3 Wilcox, H. C., Kuramoto, S. J., Lichtenstein, P., Långström, N., Brent, D. A., & Runeson, B. (2010). Psychiatric morbidity, violent crime, and suicide among children and adolescents exposed to parental suicide: A cohort study of 500,000 Swedish children. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(7), 697–701.

4 Brent, D. A., Melhem, N. M., Donohoe, M. B., & Walker, M. (2009). The long-term impact of the death of a parent on children’s psychiatric symptoms and functioning. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(9), 1049–1057.

5 Cerel, J., Fristad, M. A., Weller, E. B., & Weller, R. A. (2000). Suicide-bereaved children and adolescents: A controlled longitudinal examination. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(4), 405–412.

6 Feigelman, W., Jordan, J. R., & Gorman, B. S. (2009). Personal growth after suicide loss: Cross-sectional findings suggest growth in multiple domains. Death Studies, 33(7), 646–668.

7 Kõlves, K., Zhao, Y., Ross, V., Hawgood, J., Spence, S. H., & de Leo, D. (2019). Suicide and self-harm among university students: A systematic review. Archives of Suicide Research, 23(3), 397–418.

8 Harrison, O. M., Shankleton, J. L., Veldhof, M. L., & Abraham, S. P. (2021). The impact of suicide on family functioning. International Journal of Science and Research Methodology, 20(2), 45–58.

9 Turecki, G., & Brent, D. A. (2016). Suicide and suicidal behaviour. The Lancet, 387(10024), 1227–1239.

10 Brent, D. A., Melhem, N. M., Donohoe, M. B., & Walker, M. (2009). The long-term impact of the death of a parent on children’s psychiatric symptoms and functioning. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(9), 1049–1057.

11 McGoldrick, M. (2004). Legacies of loss: Multigenerational ripple effects. In F. Walsh & M. McGoldrick (Eds.), Living beyond loss: Death in the family (2nd ed., pp. 61–84). W. W. Norton & Company.

12 Levi-Belz, Y., & Gilo, T. (2020). The role of family and community in suicide bereavement: A review of current research. Death Studies, 44(3), 179–188.

13 Miller, G. E., Chen, E., & Parker, K. J. (2011). Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to chronic diseases in adulthood. Psychological Bulletin, 137(6), 959–997.

14 Jordan, J. R., & McIntosh, J. L. (Eds.). (2011). Grief after suicide: Understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors. Routledge.

© 2025 Elaina Baker