Living With Death

Randy was diagnosed with juvenile-onset, or Type 1 diabetes when he was ten years old. He heard the doctor say he probably wouldn't live past the age of 30, and that shaped his teen years and his early 20's. Randy lived for the moment, raced motorcycles, ate and drank what he wanted, fought, loved, and lived as though each day could be his last--because he believed it could.

Before we were married, Randy told me he probably wouldn't be around much longer. I didn't take him seriously for a long time. I had uncles and aunts with diabetes who were in their 60's and 70's, and I believed Randy would live a long time, too.

When Randy turned 30, he was a little bewildered that he was not only alive, but aside from the diabetes, he was pretty healthy. He decided he was going to enjoy each moment and began thinking of things he wanted to experience before he died. He flew on a helicopter, fished, hunted, bought horses, built a house, went to the races, and helped everyone he could find who needed a helping hand.

Randy never cried in front of anyone, but he cried when his son was diagnosed with diabetes at the age of 8. He felt so guilty, as though it were all his fault. He researched diabetes cures, islet tranplants, pancreas transplants, chelation, and everything he thought might help Jeremy. He figured it was too late for him, but he was determined to find a cure for Jeremy.

Randy and I were separated when he turned 40. Our life became way out of control while building the house. He was stressed, jealous of people I worked with, and he smoked, drank, and took too many prescription drugs. I thought I was at the end of my rope when I left, but my life during the next 7 months was terrible. Still, we both learned a lot about each other and ourselves during that time, and I know it made the rest of our life together better. We really loved each other.

In October of 2003 Randy had a heart attack. The doctor put stents in and started Randy on several medications. A few months later, when Randy complained about irregular heartbeat, the doctor gave him a prescription for pacerone, a form of amioderone. He went to see a diabetic specialist, quit smoking and drinking, and decided for the first time since he was 10 that he wasn't ready to die. He scheduled eye surgery to repair his vision, which had been damaged by diabetes. He wanted to walk his daughters down the aisle at their wedding, play pool, hunt, and fish with his sons. He wanted to catch Walter on Holloway or in Lake Huron. He wanted to be the one to shoot the monstrous 12 point buck behind our neighbor's farm. He wanted to watch his grandchildren grow up, teach them how to fix cars and use tools, how to ride motorcycles and quads, and how to hunt and fish. He wanted to build a race car and race it. He wanted to help his brother find a good woman so he could enjoy the kind of love Randy and I had.

In July of 2004 Randy thought he had a cold or a touch of the flu. He was weak, had no appetite, and coughed constantly, but it didn't stop him from powerwashing his mother's roof and deck, going fishing, or going to the races. By August 1 he couldn't catch his breath in spite of all the prescriptions the doctors called in for him. We took him to the emergency room, where his oxygen level was so low they put an oxygen mask on him immediately and admitted him.

For the next two days the family bantered with him at his bedside while he fought off the pneumonia that had infected every lobe of his lungs. The medication the doctor prescribed for irregular heartbeat had poisoned his lungs. According to the Physician's Desk Reference, it was supposed to be administered and monitored for 2 weeks while Randy was in the hospital. He was supposed to have regular tests on his liver and lungs because of the probability of deadly side effects. He wasn't supposed to be out in the sun at all. He didn't have any of this information; the doctor just wrote a prescription with a year of refills on it.

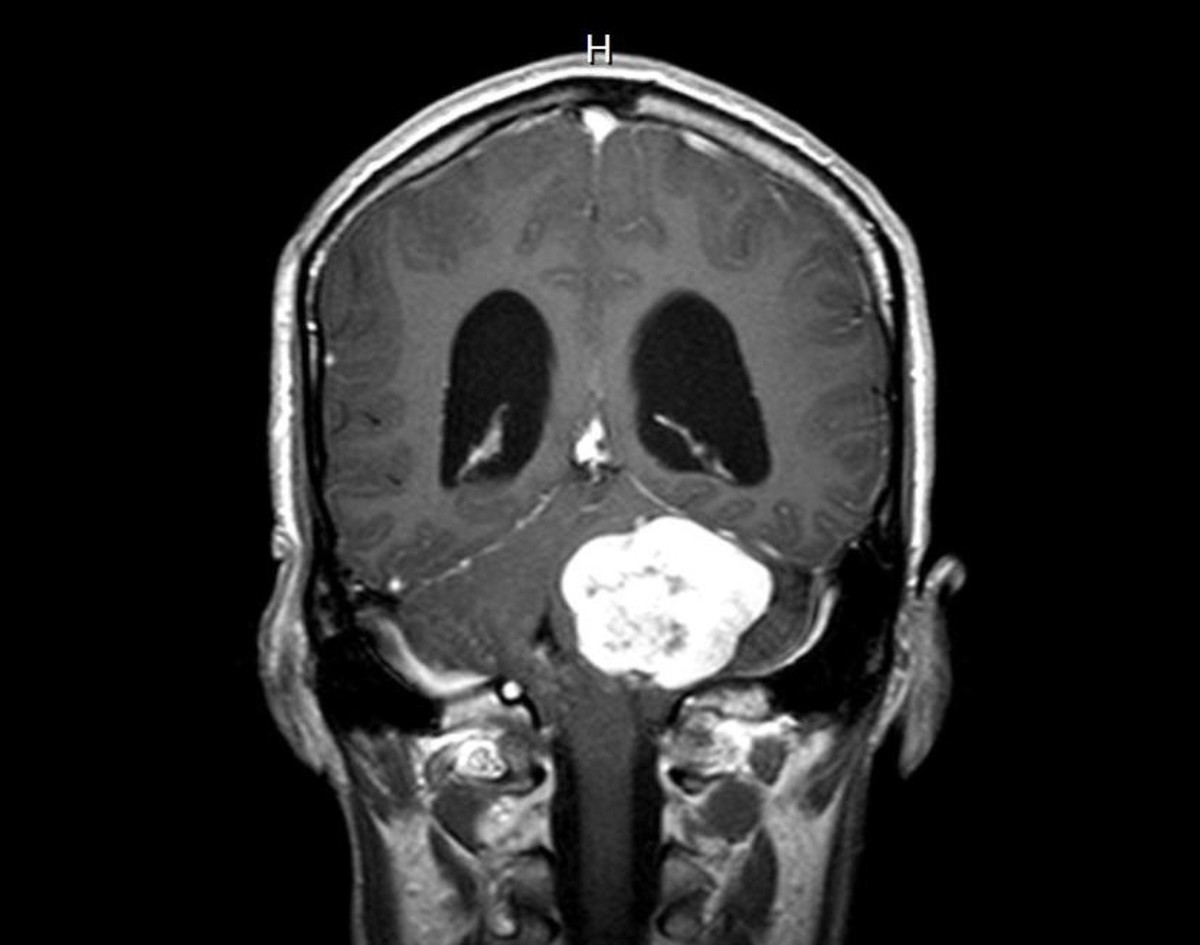

Randy wasn't responding to the breathing treatments and his legs were swollen and painful. The doctor decided to put him on a ventilator. One of the last things Randy said before they hooked him up was, "I wish I could walk just a little way down the hallway before they hook me up." Those words will always haunt me. Two days later vascular surgeons had to amputate his right leg at the waist.

Four different infections set in. The food tube wasn't providing the nutrition he needed, and he was starving. Doctors performed a bypass in his left leg to try to repair the blood vessels that were bursting because of the lack of oxygen to them, but gangrene set in and they had to amputate that leg, too. We wanted to transfer him to a teaching hospital before he lost his legs, but his kidneys were in danger, too.

My youngest daughter and I lived at the hospital for 3 weeks. We slept in the waiting room, got to know which nurses went above and beyond for him, and took a moment to run home and shower when those nurses were on duty. We jumped to our feet and held our breath every time we heard a Code Blue called. We spoke to other families with loved ones in intensive care, and we tried to get the doctors to communicate with us. Most of them were too busy covering for the heart doctor who poisoned him in the first place, but the vascular team was remarkable and one doctor on staff spent the night at the hospital more than once.

Our favorite night shift nurse, Larry, was on duty the night the doctors decided Randy had to be put on a medicine that would paralyze him to keep him from fighting the ventilator. The doctors suggested we go home for a good night's sleep since the next few weeks would be rough. My daughter and I looked at each other, and my daughter told me, "Larry's got him." Since Larry had saved his life more than once, I knew Randy would be safe with him.

And he was. Larry was administering CPR when the Code Blue that we never heard was called. He had revived Randy when the hospital called and said, "Your husband has taken a turn for the worse." He was trying to revive him while we were on our way to the hospital, while I repeated a prayer over and over: "Please wait for us, baby, please wait for us." And he was still pumping on Randy's chest when I ran into the room calling for him.

The doctor whisked me out of the room and told me, "I think it's time to let him go." I froze. I couldn't speak, think, or breathe. Not once during the whole ordeal did I believe God would take him. He was so alive, even when he was heavily drugged, hooked up to so many machines and couldn't speak.

At one time, Randy asked my daughter and I about his leg with hand motions and forming the words he couldn't speak. We had been told not to mention it, but we had been reading his lips for two days, and he needed to know what happened to his leg. I said, "Your leg?" He nodded, and he looked so relieved and grateful that someone finally understood. I swallowed. "We've been so worried about you. Blood vessels started breaking in your legs because they weren't getting any oxygen. They operated on your right leg and did a bypass on your left leg, and when you're off that ventilator you can ask the doctors anything you want." He nodded, then he winked and blew me a kiss. How could I let someone die who fought so hard, who loved so much, who had decided he wanted to live?

My daughters came in, and the youngest asked what was going on. My eyes were glued to the doctor's as I reached out and wrapped my arms around her. The doctor patiently repeated what he had said to me: "I think it's time to let him go."

I felt every muscle in my daughter's body tense and I held on tight as she leaped toward the doctor, screaming, "No! It's not his time! He has to walk me down the aisle at my wedding! He has to be there when my children are born!" When she calmed down, she asked if we could see him first. The doctor hesitated, then said, "They're still pushing on his chest." My daughter responded, "I don't care!"

I think he was already gone before we said goodbye, even though the team was keeping his body alive. More blood vessels were breaking, and one traveled to his lungs. Because of the diabetes, doctors couldn't help him. I remembered a doctor who had said years before, "Diabetics who smoke die young without exception." Randy bent the rules, and it took them a long time to break. But that's how a diabetic's body works. You don't follow the rules, and your body keeps bending and bending like a branch on a tree until a number of years later, when everything snaps and can't be fixed.

Losing Randy is the worst thing I've ever been through. Learning to live without him is the hardest thing I've ever done. I watch my daughter with her little girl, and my stepson with his little boy, knowing one of their biggest regrets is that their children didn't get to know Papa. And I know it's one of Randy's biggest regrets, too.