The Grain Beneath the Pyramid: Unpacking the Politics and Myth of America's Dietary Guide

Beneath the Pyramid: A Monument to Industry, Not Nourishment

For over a generation, the U.S. Food Pyramid loomed large in the American psyche—a geometric gospel of health, etched into the margins of school textbooks, whispered through public service announcements, and emblazoned across cereal boxes like sacred scripture. It promised clarity in a chaotic nutritional landscape, offering a simple visual hierarchy of what to eat and how much. At its wide, sturdy base: wheat, bread, pasta, and cereal—prescribed in generous abundance, 6 to 11 servings a day.

But beneath its clean lines and institutional authority lay a far more complex story—one not of scientific consensus, but of political compromise, economic entanglement, and cultural erasure. The pyramid was not born solely from nutritional wisdom. It was shaped—sometimes distorted—by the hands of lobbyists, agricultural giants, and bureaucrats tasked with promoting both public health and commodity sales. In that dual mandate, the pyramid became less a guide to nourishment and more a monument to industrial grain.

Why such reverence for wheat? Why did refined carbohydrates become the foundation of American dietary advice? The answers lie in a web of Cold War-era food surplus management, the rise of industrial agriculture, and the lobbying power of grain producers who saw in the pyramid not just a public health tool, but a marketing opportunity. Whole grains were conflated with refined ones. Cultural foodways were flattened into a Western-centric model. And the nuanced science of metabolism, satiety, and glycemic load was sacrificed for simplicity and scale.

The consequences were profound. Millions followed the pyramid’s advice, trusting its authority. Yet as obesity, diabetes, and metabolic disorders surged, critics began to ask: Was this guidance truly about health—or about selling wheat?

This article unearths the story behind the pyramid’s creation and legacy. It traces how a symbol of wellness became a vessel for industry, and how reclaiming our nutritional autonomy means not just rethinking what we eat—but reimagining who gets to define nourishment in the first place.

A Pyramid of Compromise: How Sweden’s Simplicity Became America’s Industrial Blueprint

The original concept of the Food Pyramid was born not in the United States, but in Sweden during the early 1970s—a pragmatic response to rising food prices and growing public confusion about nutrition. Swedish officials sought to create a visual tool that could guide citizens toward affordable, balanced eating. It was modest, intuitive, and rooted in public welfare.

But when the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) adopted and reimagined the pyramid in 1992, its purpose began to shift. Unlike Sweden’s public health-first approach, the USDA carried a dual mandate: to promote agricultural commodities and to provide nutritional guidance. This paradox—serving both the farmer and the eater—created a deep and enduring conflict of interest. The pyramid was no longer just a map for health; it became a billboard for American agribusiness.

It’s important to note that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), often conflated with the USDA in public discourse, was not responsible for the pyramid’s design. The FDA oversees food labeling and safety, but the USDA shaped the dietary guidelines that would influence school lunches, hospital meals, and national policy.

Nutrition scientists initially proposed a more balanced model—one that emphasized whole foods, limited refined carbohydrates, and acknowledged the value of healthy fats. But their recommendations collided with powerful lobbying forces. Grain, dairy, and meat industries, fearing reduced consumption and profit loss, pressured policymakers to revise the pyramid in their favor.

According to renowned nutrition scholar Marion Nestle, PhD, MPH, over 30 changes were made to the original draft to appease food producers. These edits diluted scientific integrity, blurred distinctions between whole and processed foods, and elevated certain commodities—not because they were healthiest, but because they were most politically protected.

Thus, the pyramid became a symbol not of nutritional clarity, but of institutional compromise. It was a structure built not just from grains and guidance, but from the invisible scaffolding of corporate influence and cultural bias.

A Foundation of Flour: How Grains Became the Sacred Base of American Nutrition

At the very base of the U.S. Food Pyramid—its widest and most emphasized tier—sat a daily prescription of 6 to 11 servings of bread, cereal, rice, and pasta. This wasn’t a gentle suggestion; it was a foundational decree, shaping the eating habits of millions and reinforcing the idea that grains were the cornerstone of health.

But this emphasis was never purely scientific. It was economic, political, and deeply strategic.

The grain industry—particularly wheat and corn producers—wielded immense influence over agricultural policy and public nutrition messaging. These commodities were abundant, subsidized, and central to American agribusiness. By anchoring the pyramid in grain-based products, policymakers ensured a steady demand for surplus crops, stabilized commodity prices, and supported the interests of powerful lobbying groups.

In this process, a crucial distinction was erased: whole grains, rich in fiber and nutrients, were lumped together with refined carbohydrates—white bread, sugary cereals, instant rice, and pasta stripped of their original integrity. The pyramid made no visual or verbal effort to separate the nourishing from the processed. It treated all grains as equal, regardless of their metabolic impact or nutritional density.

This conflation had far-reaching consequences. It normalized the overconsumption of refined carbs, fueling a boom in ultra-processed food production. Supermarket shelves filled with low-fat, high-carb products marketed as “healthy” simply because they fit the pyramid’s grain quota. Meanwhile, rates of obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes began to climb—especially among communities already vulnerable to food insecurity and systemic health disparities.

The pyramid’s grain-heavy foundation wasn’t just a dietary recommendation—it was a cultural script. It taught generations to trust the processed over the whole, the industrial over the ancestral. It turned flour into gospel and convenience into virtue.

To reclaim our health, we must first question the altar we were taught to worship at—and remember that nourishment is not just about what fills the plate, but what fuels the soul.

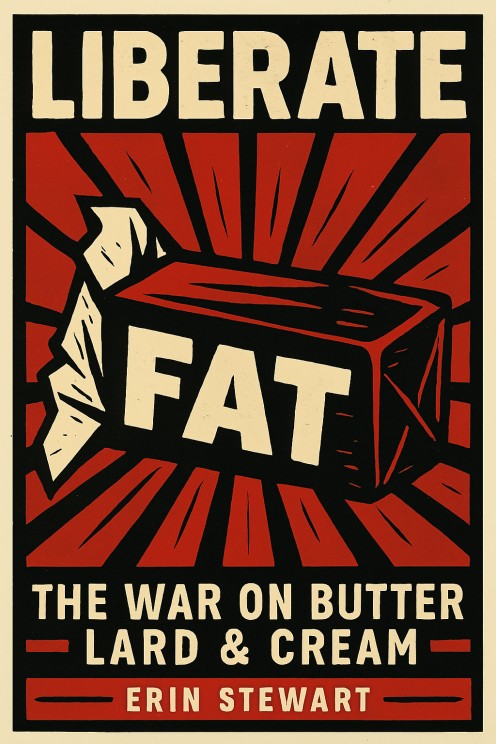

The War on Fat: How Fear, Flawed Science, and Industry Shaped a Nutritional Myth

In the 1970s and 1980s, a seismic shift occurred in the American understanding of nutrition. Dietary fat—once a revered source of satiety and ancestral nourishment—was cast as the villain in the nation’s health narrative. This transformation wasn’t born from holistic inquiry or cultural wisdom, but from a series of oversimplified studies that linked fat consumption to rising rates of heart disease.

One of the most influential voices in this shift was Ancel Keys, whose Seven Countries Study suggested a correlation between saturated fat intake and cardiovascular illness. Though the study had methodological flaws and excluded data that contradicted its conclusions, it gained traction in policy circles and media headlines. Fat became the scapegoat, and the public was urged to purge it from their plates.

The result was a sweeping push for low-fat diets—an era of margarine, fat-free yogurt, and snack foods engineered to meet the new gospel. But in removing fat, something else had to fill the void. That “something” was sugar, refined grains, and synthetic additives. Food manufacturers capitalized on the trend, flooding the market with products labeled “low-fat” or “fat-free,” often loaded with high-fructose corn syrup and emulsifiers to mimic the mouthfeel of real fat.

The Food Pyramid, introduced in 1992, echoed this fear-driven narrative. It failed to distinguish between nourishing fats—like those found in nuts, seeds, avocados, olives, and cold-water fish—and harmful ones, such as trans fats and hydrogenated oils. By lumping all fats into a single cautionary category, the pyramid inadvertently encouraged the public to avoid beneficial fats entirely.

This omission had profound consequences. Omega-3 deficiencies became common. Hormonal imbalances, mood disorders, and metabolic dysfunctions surged. The body, deprived of its essential building blocks, began to fray at the edges.

Fat was never the enemy. The true danger lay in the erasure of nuance—in the reduction of complex biochemistry to a binary of “good” and “bad,” and in the silencing of ancestral knowledge that understood fat not as poison, but as medicine, ritual, and sustenance.

To heal this legacy, we must restore fat to its rightful place—not just on the plate, but in the cultural imagination. We must remember that nourishment is not a war of macronutrients, but a dance of balance, context, and care.

Consequences: A Nation Misfed

The Food Pyramid’s guidance—positioning grains as the dietary foundation and casting fat as a nutritional threat—ushered in a sweeping cultural shift. Americans, trusting the authority of government-backed nutrition, embraced low-fat, high-carbohydrate diets with fervor. But in doing so, they often replaced ancestral wisdom and whole-food traditions with convenience and compliance.

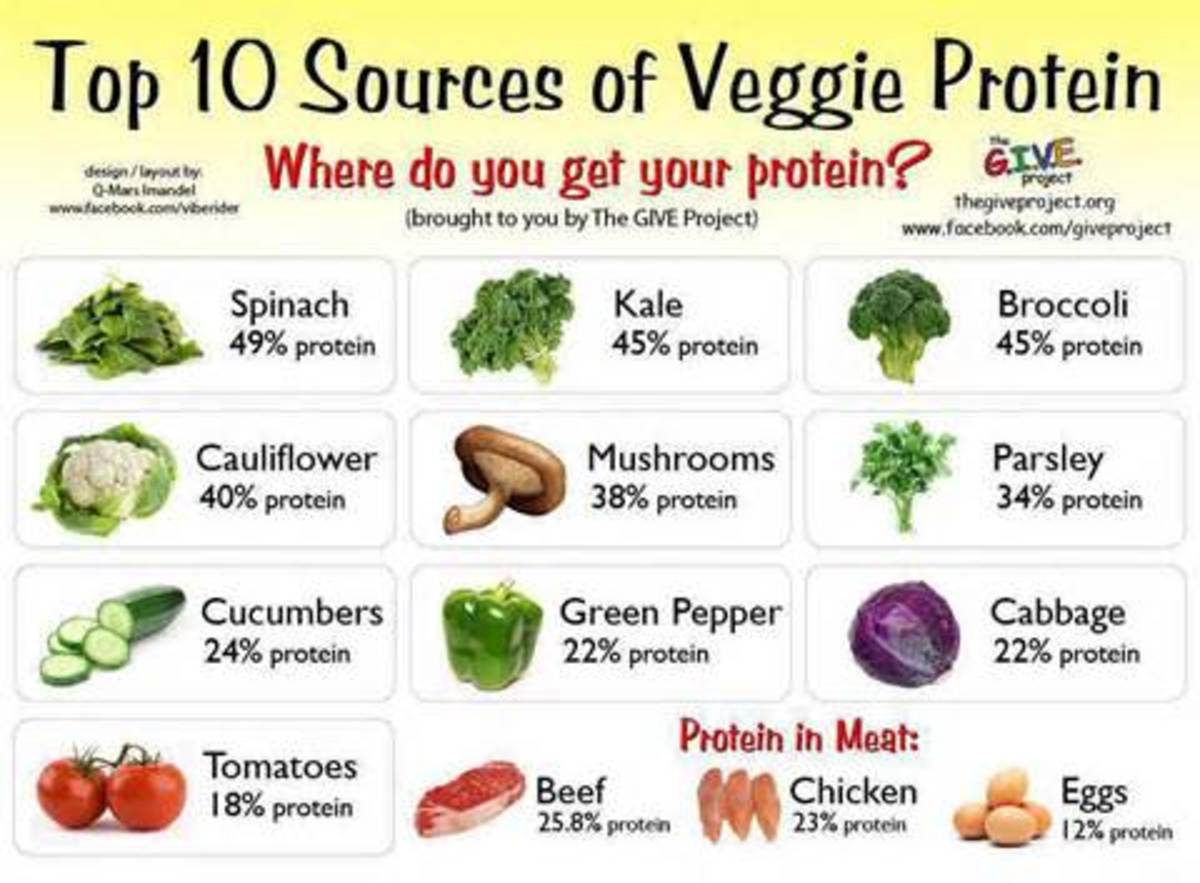

White bread, sugary cereals, instant rice, and pasta became daily staples, crowding out vibrant vegetables, nourishing fats, and quality proteins. The pyramid’s visual hierarchy implied abundance without discernment—suggesting that more grains meant better health, regardless of their refinement or glycemic impact.

Between 1980 and 2018, the consequences became painfully visible. Obesity rates in the United States more than doubled. Type 2 diabetes surged across age groups. Metabolic syndrome—once a clinical term—became a household reality. These weren’t isolated outcomes; they were systemic, unfolding across communities, generations, and socioeconomic lines.

Critics argue that the pyramid’s design didn’t just misguide—it normalized dysfunction. By failing to distinguish between whole and refined grains, it encouraged the rise of ultra-processed foods. By omitting clear guidance on sugar intake and portion control, it left consumers vulnerable to marketing manipulation and addictive eating patterns. And by marginalizing healthy fats, it disrupted hormonal balance, satiety cues, and ancestral dietary rhythms.

The pyramid became less a tool for nourishment and more a blueprint for imbalance. It taught people to fear fat, trust flour, and equate fullness with health. It shaped not just meals, but mindsets—embedding a nutritional myth that still echoes through food policy, public health campaigns, and family kitchens.

To heal this legacy, we must do more than revise guidelines. We must restore nuance, honor cultural diversity, and reclaim the sacred relationship between food and vitality. Nourishment is not a formula—it is a ritual, a rhythm, and a remembering.

Cultural Myth and Nutritional Truth

The Food Pyramid did more than prescribe what Americans should eat—it quietly reshaped how they saw themselves. It became a tool not just of dietary instruction, but of cultural imprinting. By elevating a narrow, Western-centric model of nutrition, the pyramid imposed a homogenized vision of health that sidelined ancestral foodways, indigenous wisdom, and holistic traditions rooted in seasonality, ceremony, and ecological intimacy.

In many cultures, grains are indeed sacred—woven into myth, ritual, and daily life. But they are rarely consumed in isolation. They are balanced with fermented foods that nourish the microbiome, wild greens that offer mineral-rich medicine, and fasting practices that honor the rhythms of the body and spirit. These traditions reflect a deep understanding of food as relationship—not just fuel, but communion with land, lineage, and the unseen.

The pyramid flattened this nuance into a one-size-fits-all diagram, stripping food of its cultural context and spiritual significance. It treated nourishment as a universal equation, ignoring the diversity of metabolic needs, climate-based adaptations, and ancestral practices that have sustained communities for millennia. It privileged industrial grains over heritage crops, convenience over ritual, and quantity over quality.

In doing so, it contributed to a subtle form of nutritional colonialism—where Western science was positioned as the sole authority, and other ways of knowing were dismissed as anecdotal or outdated. The result was not just dietary imbalance, but identity erosion. People were taught to distrust their grandmother’s broth, their village’s fermented staples, their sacred fasting days—and instead to count servings from a chart designed in a boardroom.

To reclaim nourishment, we must first reclaim story. We must honor the foods that carry memory, the meals that mark transitions, and the wisdom that lives in the hands of elders and the soil beneath our feet. True nutrition is not just about what we eat—it’s about how we remember who we are.

From Pyramid to Plate: A New Shape, Same Shadows

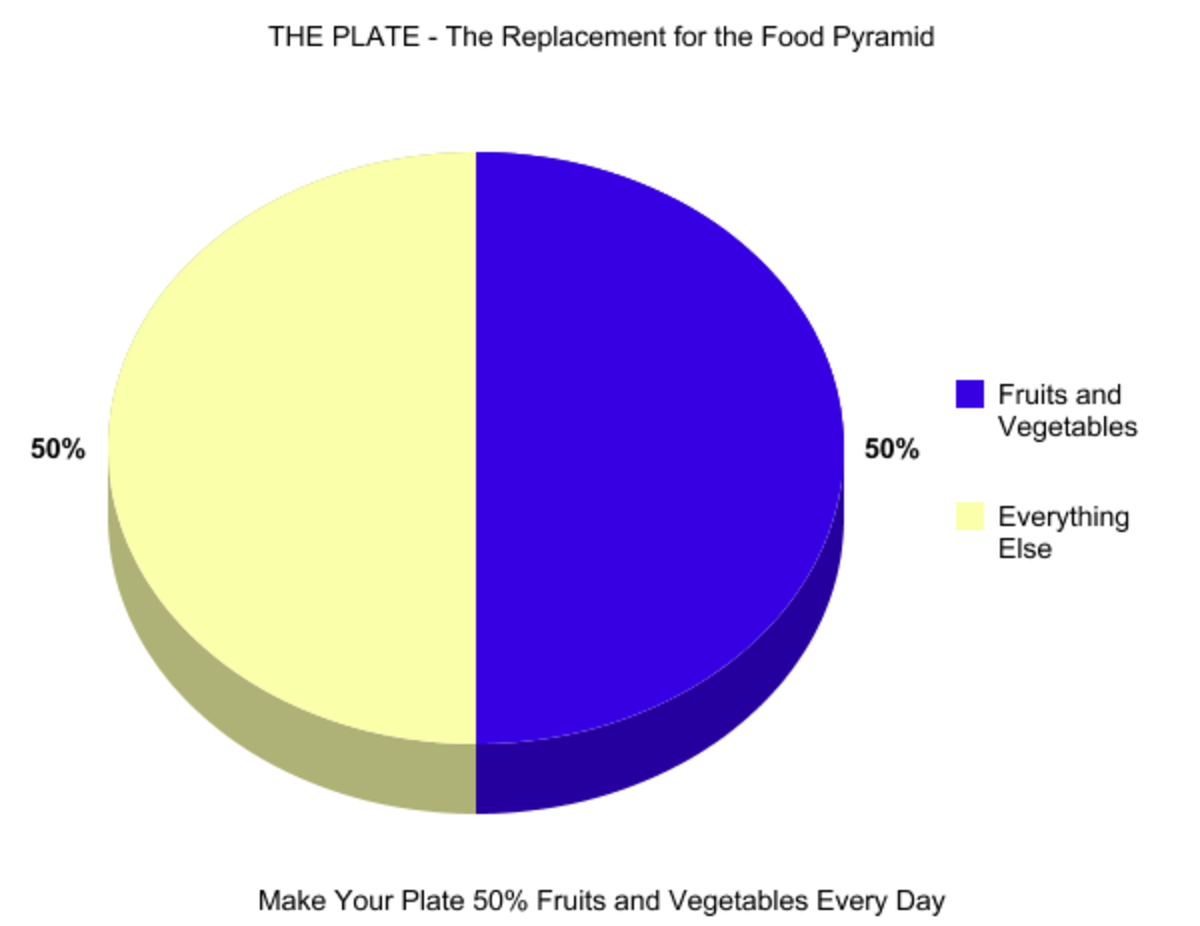

In 2011, the U.S. Department of Agriculture unveiled MyPlate—a sleek, circular icon designed to replace the aging Food Pyramid. With its clean divisions and simplified layout, MyPlate aimed to make nutrition more intuitive: half the plate for fruits and vegetables, the other half split between grains and protein, with a side of dairy hovering like a satellite. It was a visual shift from hierarchy to balance, from towering geometry to everyday tableware.

On the surface, MyPlate marked progress. It abandoned the confusing tiers of the pyramid and emphasized portion awareness over rigid food group dominance. It encouraged Americans to visualize their meals in real time, offering a more practical guide for daily choices.

But beneath its polished veneer, MyPlate still carried the imprint of its predecessor’s compromises. It continued to reflect the influence of powerful agricultural lobbies—particularly dairy, grain, and meat industries—whose products remained prominently featured. The plate’s design, while more accessible, still lacked cultural adaptability and failed to honor the diverse food traditions that nourish communities across the globe.

There was no space for fermented staples, no acknowledgment of plant-based alternatives to dairy, no room for fasting rhythms or ceremonial eating. MyPlate assumed a static, Western meal structure—three square meals, each plated with symmetry and predictability. It left little room for ancestral nuance, seasonal variation, or the emotional and spiritual dimensions of nourishment.

In essence, MyPlate changed the shape but not the story. It softened the edges of nutritional dogma without dismantling the industrial scaffolding beneath it. It offered a more digestible image, but still asked the public to consume a narrative shaped by commodity interests rather than cultural wisdom.

To truly evolve, our dietary guides must do more than rearrange portions. They must listen—to elders, to ecosystems, to the body’s whispers and the soul’s hunger. They must reflect not just what we eat, but how we live, remember, and belong.

Toward a More Honest Guide

To truly reclaim nutritional sovereignty, we must do more than revise food charts or swap one guideline for another. We must awaken from the trance of industrial nutrition and return to the sacred, the seasonal, and the soul-fed. This reclamation is not just about what we eat—it’s about who we trust, how we remember, and what stories we choose to nourish.

Here’s how we begin:

1. Decenter Industry Influence from Public Health Policy

We must dismantle the scaffolding of corporate interests that shape national dietary recommendations. Public health should not be dictated by commodity sales or lobbyist agendas. It must be rooted in independent science, ecological sustainability, and the well-being of communities—not the profit margins of grain, dairy, or processed food conglomerates.

2. Honor Diverse Food Traditions and Ancestral Wisdom

Nutrition is not universal—it is cultural, climatic, and ancestral. We must uplift indigenous foodways, diasporic culinary practices, and the healing rituals of elders who know how to feed both body and spirit. From fermented maize in Mesoamerica to bone broths in East Asia, from foraged greens in Africa to sacred fasts in the Middle East—these traditions carry wisdom that modern charts cannot contain.

3. Differentiate Between Whole and Refined Foods—Especially Grains

We must restore discernment to our plates. Whole grains, rich in fiber and life force, are not the same as bleached flour or sugar-laced cereals. The conflation of these foods in past guidelines has led to metabolic confusion and cultural erasure. Let us name the difference, honor the integrity of whole foods, and resist the normalization of the ultra-processed.

4. Include Emotional, Cultural, and Ritual Dimensions of Eating

Food is not just fuel—it is memory, ceremony, and connection. We must expand dietary frameworks to include the emotional resonance of meals, the cultural significance of ingredients, and the rituals that turn eating into healing. Whether it’s a grandmother’s stew, a sabbath feast, or a quiet moment of gratitude before a simple bowl of rice—these acts matter. They shape our relationship to nourishment and to each other.

Closing Reflection

The Food Pyramid was never just a flawed diagram—it was a mirror of its era, etched with the anxieties, ambitions, and blind spots of a nation grappling with health through the lens of industry. It was shaped by fear of fat, faith in mass production, and a science stripped of soul. Beneath its geometric simplicity lay a deeper story: one of reductionist thinking, political compromise, and the quiet erasure of ancestral wisdom.

It taught generations to measure nourishment in servings and percentages, not in vitality, ritual, or relationship. It turned food into formula, and in doing so, distanced us from the sacred intimacy of eating—the kind passed down through grandmothers’ hands, seasonal harvests, and the quiet knowing of the body.

But we are not bound to its legacy.

As we move forward, may our nutritional guides be more than charts—they must be invitations. Invitations to integrity, where science is transparent and unshackled from corporate influence. Invitations to pluralism, where diverse foodways are honored, not flattened. Invitations to nourishment that feeds not only the body, but the memory, the spirit, and the collective pulse of our communities.

Let us build frameworks that remember the wildness of the earth, the wisdom of the elders, and the emotional truth of hunger. Let us eat not just to survive, but to belong—to ourselves, to each other, and to the living story of what it means to be well.

References

Nestle, M. (2002). Food politics: How the food industry influences nutrition and health. University of California Press.

End to End Health. (n.d.). How lobbyists changed the food pyramid. Retrieved September 17, 2025, from https://www.endtoendhealth.com/how-lobbyists-changed-the-food-pyramid

StudyLib. (n.d.). Food Politics: USDA & the Food Pyramid Controversy. Retrieved September 17, 2025, from https://studylib.net/doc/5359499/-1991--the-eating-right-pyramid

Where the Food Comes From. (2025). USDA’s 2025 Dietary Guidelines: Key findings, recommendations, and public comment opportunities. Retrieved September 17, 2025, from https://wherethefoodcomesfrom.com/usdas-2025-dietary-guidelines-key-findings-recommendations-and-public-comment-opportunities

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2025 Erin K Stewart