Unboxing Depression

What is Depression?

The DSM-5 (The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition) categorizes depression (i.e. mood disorder leading to disinterest and sadness) into the following types (Chand & Arif, 2020).

- Depressive disorder due to comorbidity

- Premenstrual dysphoric disorder

- Dysthymia (persistent depressive disorder)

- Major depressive disorder

- Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder

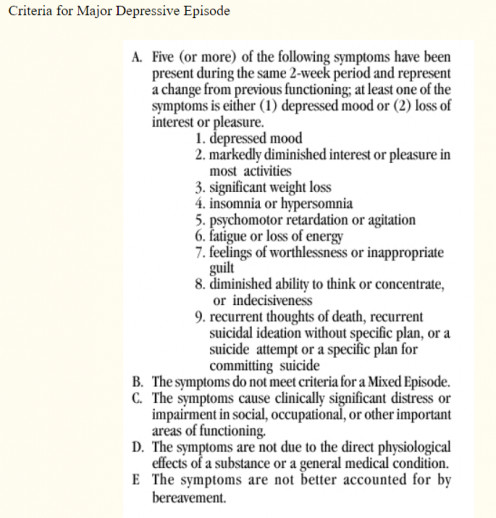

The preliminary attributes of various depressive states include cognitive changes, somatic deterioration, irritable mood, emptiness, and sadness. The depressed people majorly experience false perceptions and eventually do not make any attempt to acquire medical intervention. Depressed people tend to hide their depressive states based on their irrational apprehension. Societal stigma profoundly obstructs the passage of medical assistance for depressed people. Depression control therapies induce different therapeutic responses in individuals of various age groups and characteristics. Clinically, the presence of any 5 symptoms from the following list affirms the diagnosis of depression in the suspected patients.

- Suicidal thoughts

- Psychomotor disturbance

- Reduction in interest or pleasure

- Fatigue or reduced energy

- Mood deterioration

- Attention-deficit

- Weight/appetite changes

- Worthlessness or feeling of guilt

- Sleep disturbance

The feeling of worthlessness among depressed people in many situations forces them to develop self-harm tendencies that eventually become the causative factors for their suicidal attempts. The physicians require thoroughly understanding depression complications for effectively customizing their holistic and person-centered treatment strategies. These complications include delusions, vegetative/physical symptoms, motivational constraints, cognitive complications, and emotional inconsistencies. The psychotic depression is a form of severe depression manifested by hallucinations and delusions (Paykel, 2008). Such type of depression requires treatment through a blend of interventions including antipsychotic drugs and electroconvulsive therapy. Endogenous depression is characterized by prolonged sadness that drastically deteriorates the psychosocial and physical functions of the affected individuals. This type of major depressive disorder develops under the impact of environmental, psychological, biological, and genetic factors.

What are the Causes of Depression?

The psychological and biological causes of depression variably impact the health and wellness of people following their circumstances. Some of the potential causes of depression are mentioned below (IQWiG, 2006).

- The winter season and dark fall negatively impact the mood and temperament of individuals while elevating their risk for depressive complications.

- Loneliness is one of the commonly reported causes of depression that adversely impacts psychosocial outcomes.

- The elevated stress, negative perceptions, under-challenged feelings, and reduced coping skills potentially reduce the psychological stability of individuals, thereby elevating their risk for depression.

- Adverse childhood experiences or distressing episodes based on relationship conflicts and death of relative/friend potentially increase the affected individual’s predisposition towards mental instability and depression.

- Prolonged use of medications also leads to the onset and establishment of depression in treated individuals.

- The medical conditions including underactive thyroid, cancer, heart attack, and stroke elevate the risk of depression in the affected patients.

- Drug addiction, substance abuse, and alcoholism for an extended tenure elevate the risk of depression in addicted individuals.

- Limited self-confidence is a personality trait that increases the risk of depression and related psychosocial complications.

- The biochemical alterations inside the human body potentially contribute to the occurrence of depressive episodes. For example, the nerve impulses of depressed people travel at a reduced pace as compared to healthy individuals. Furthermore, the hormonal pathways and chemical messengers also deviate from their normal physiological trends in depressed individuals.

- The sense of insecurity, reduced self-esteem, puberty, and childhood anxiety disorders elevate the frequency of depression in the affected people.

- The episodes of neglect and abuse and other traumatic childhood experiences also elevate the risk of depression and mental health complications.

- A family history of depression/mental health issues potentially elevates the predisposition of individuals towards experiencing depressive symptoms.

The emotional conditions like nostalgia profoundly impact the mental health and behavioral outcomes of individuals (Kanter, Busch, Weeks, & Landes, 2008). The depressed people experience a marked reduction in their positive reinforcement potential and resultantly experience cognitive symptoms, somatic manifestations, and fatigue. The people who have a disinclination towards socialization acquire isolation for an extended period. Their emotional responses against socialization also make them the victim of depression. Other significant causes of depression include job losses, socioeconomic or financial constraints, homemaking requirements/demands, workload elevation, and mild/chronic stressors. Furthermore, young females with a family history of mental disease and reduced income also experience a high-risk for major depression and related psychosocial complications (Meng et al., 2017).

What are the Risk Factors of Depression?

The risk factors of depression are categorized into the following biophysical, psychological, social, spiritual, and miscellaneous attributes (American Mental Wellness Association, 2020) (McCarter, 2008).

Biophysical Risk Factors

- Sleeping issues/sleeplessness

- Poor nutrition/dietary deficiency

- Drug addiction

- Genetic influence

- Alcoholism

- Parkinson’s disease

- Alzheimer’s dementia

- Hypothyroidism

- Chronic mental health complications

- History of brain trauma

- Pregnancy complications

- Birth-related complications

- Family history of mental disorders

Psychological Risk Factors

- Academic failure

- Negative outlook for life

- Incompetence

- Inappropriate perceptions/apprehension

- Reduced self-esteem

- Deployment in armed forces

- History of mental trauma

- History of physical trauma

- Lawbreaking attempts

- Financial issues

Social Risk Factors

- Limited health care access

- Limited socialization

- Inaccessible social support services

- Discrimination

- Reduced communication

- Poor psychosocial skills

- Poverty

- Victimization through perpetration and bullying

- Divorce, death, and/or bereavement

- Limited friend circle

- Constrained friendly relationships

- Engagement in abusive conduct or relationship

- Childhood trauma, including physical misconduct, abuse, neglect, and psychosocial abuse

Spiritual Risk factors

- Religious restrictions

- Disturbed thought process

- Insignificant perceptions

- Irredeemable perceptions

Miscellaneous Risk Factors

- History of arrhythmia

- History of coronary artery atherosclerotic disease

- History of myocardial infarction

- History of transient ischemic attack

- History of cerebrovascular disease/stroke

- History of domestic violence

- History of venereal abuse

- History of alcohol/drug abuse

- Depression history of 1st-degree relative

- History of eating difficulties

- History of stress and anxiety

- Female gender

What are the Protective Factors of Depression?

The protective factors of depression are categorized into the following biophysical, psychological, social, and spiritual attributes (American Mental Wellness Association, 2020) (McCarter, 2008).

Biophysical Protective Factors

- Exercise

- Healthy diet

- Engagement in mental health enhancement activities

- Establishing secure attachments with individuals

Psychological Protective Factors

- Selection of healthy beverage and food options

- Inclusion of dairy products, proteins, grains, vegetables, and fruits in dietary regimen

- Optimism

- Self-sufficiency enhancement

- Enhancement of problem-solving/coping skills

- Enhancement of emotional self-regulation ability

- Enhancement of self-discipline at work, school, and home

- Enhancement of caregivers’ discipline and support

Social Protective Factors

- Elevated access to health care services and social support interventions

- Financial and socioeconomic stability

- Elevated participation in religious gatherings, community-based interventions, and sport activities

- Enhanced supportive relationships with caretakers, family members, peers, and friends

Spiritual Protective Factors

- Enhanced moral beliefs

- Enhancement of motivation achievement feeling

- Enhanced orientation towards spiritual practices, faith conventions, and belief systems

What is the Pathophysiology of Depression?

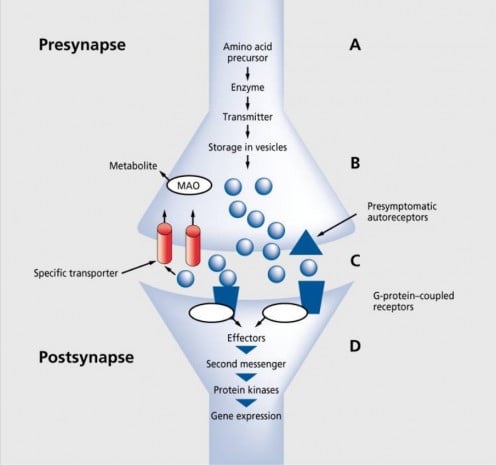

Synaptic or Chemical Transmission

Synaptic transmission is based on the secretion, storage, and transmission of neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft across pre/postsynaptic neurons (Brigitta, 2002). The chemical transmission also reciprocates with cellular responses/signal transduction cascade initiation and neurotransmitter action termination. The neurotransmitters’ synthesis begins with the systematic amino acids’ transportation into the cerebral/cerebellar regions. The neurotransmitters’ release/transportation into the human brain is a calcium channel-dependent process that effectively controls neuronal transmission rate in human beings. Secondly, a similar process is induced by drugs that attempt to modify neurotransmitters’ release mechanisms and related processes (Brigitta, 2002). The engagement of somatodendritic receptors in neurotransmitters’ regulatory mechanisms potentially decreases their synthesis under the influence of environmental factors. The termination of synaptic effects is preceded by the locking of transporter proteins with their specific transmitters that further interact with presynapse for their enzymatic metabolization. The monoamine hypothesis affirms the functional deficiency of dopamine, 5- hydroxytryptamine (HT), and norepinephrine (i.e. monoaminergic transmitters) as the preliminary cause of clinical depression. However, monoamines’ elevated concentration across brain synapses leads to the development of mania. The monoamine system not only mediates depression mechanism but also facilitates the therapeutic actions of various antidepressant drugs (Brigitta, 2002).

Hormonal Abnormalities

The hormonal abnormalities associated with depression include thyroid function dysregulation, hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis dysfunction, endocrine disturbances, thyroid hormone imbalance, growth hormone alteration, and cortisol imbalance. Some of the significant hormonal causes of depression include the following (Brigitta, 2002).

- HPA axis suppression impairment

- Elevated cortisol level

- Inappropriate glucocorticoid feedback

- Hypothalamic CRH (corticotropin-releasing hormone) hypersecretion

Immunocompromised Status

The immune system impairment potentially impacts mental health outcomes while elevating the level of stress and depression (Brigitta, 2002). The stressful circumstances of life including bereavement, divorce, and examination pressure potentially disrupt cellular immune mechanisms while deteriorating the activity of natural killer cells and lymphocytes. The immune system enhancement in these scenarios proves to be the best remedy for reducing the depressive state of the immunocompromised people (Brigitta, 2002). Furthermore, the exogenous cytokines including interferon-α and interleukin-2 deteriorate mood and immune system in a manner to increase the risk of depression. The elevated concentration of these cytokines disrupts flexible thinking patterns, motivation levels, and cognition of depressed individuals. Cytokines’ elevation also increases stress reaction and somatic complications that predominantly result in the development of a depressive state (Brigitta, 2002).

What are the Diagnostic Tests/Measures for Depression Assessment?

Physicians recommend the use of the following measures for depression evaluation of the suspected patients.

- Affirmation of the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) depression criteria by a mental health professional helps in diagnosing the episodes of major depressive disorder (Mayo Clinic, 2020).

- Psychiatric assessment comprehensively assists the health care professionals to systematically evaluate behavioral pattern, feelings, thoughts, and symptoms associated with clinical depression (Mayo Clinic, 2020).

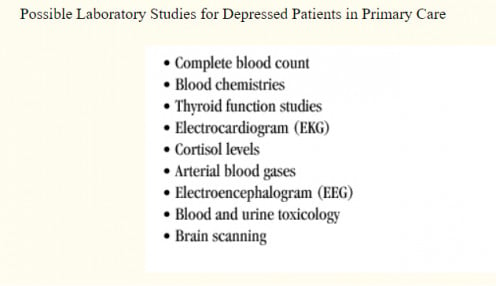

- Laboratory investigations including thyroid assessment and hemogram help in evaluating pathophysiological complications for their clinical correlation with mental health changes of the depressed patients (Mayo Clinic, 2020).

- Physical examination helps in tracking the physical health issues and body system complications responsible for the development of depressive symptoms (Mayo Clinic, 2020).

- MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) brain and PET (positron emission tomography) scan assist in evaluating or ruling out the occurrence of brain atrophy and ventricle-brain volume elevation in the patients suspected for depression (Brigitta, 2002).

- Brain imaging also helps in evaluating the structural abnormalities in basal ganglia, frontal brain lobe, and hippocampus of the suspected depression patients (Brigitta, 2002).

- The assessment of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes including CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, and CYP3A is highly required to formulate the appropriate pharmacotherapy for depression. This is because these enzymes prove to be the deciding factors for metabolizing a range of antidepressant drugs and their products (Brigitta, 2002).

- The assessment of pharmacodynamic variability is required to evaluate genetic variations responsible for signal transduction cascade episodes, receptor functions, and monoamine uptake regulation in depressed patients (Brigitta, 2002).

What are the Most Common Drugs for Depression Treatment?

The physicians conventionally prescribe the following types of antidepressant drugs based on the reported clinical symptoms of depressed patients (Blackburn, 2019).

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors help in reducing depression while increasing the function of monoamines.

- Tricyclic antidepressants help in enhancing the process of neurogenesis by acting on the 5HT1A receptor of depressed patients.

- Atypical antipsychotics including aripiprazole, ziprasidone, olanzapine, and clozapine belong to a separate class of antidepressants and assist in controlling depressive symptoms.

- SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) act on the level of 5-hydroxytryptamine while increasing the brain’s serotonin level. Some of the commonly used SSRIs include sertraline, paroxetine, fluoxetine, escitalopram, and citalopram.

- SNRIs (serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors) enhance the communication network of the brain cells in a manner to enhance their mood regulation potential. Some of the commonly used SNRIs include venlafaxine, levomilnacipran, duloxetine, and desvenlafaxine.

How to Prevent Depression?

Some of the meaningful strategies for depression prevention are listed below. The systematic use of these interventions helps in controlling depression symptoms and mitigating mental health complications of distressed individuals.

- Avoidance of depression triggers: Stressful situations generate depression triggers that potentially disrupt hormonal concentrations, particularly among women (Albert, 2015). Accordingly, individuals must try to avoid or overcome stressful circumstances through mindful techniques for reducing their risk for depression.

- Tobacco smoking cessation: Tobacco/cigarette smoking for an extended period potentially elevates the risk of anxiety and depression. Accordingly, avoidance of smoking helps in relieving social anxiety, psychological stress, and depression complications (Fluharty, Taylor, Grabski, & Munafò, 2017).

- Reduced utilization of drugs/substances and alcohol by the individuals affected with alcohol use disorder substantially reduces their risk of depression (Conner, Pinquart, & Gamble, 2009).

- Increased awareness of the adverse effects of depression medications helps concerned patients to reduce their risk of clinical complications (Cartwright, Gibson, Read, Cowan, & Dehar, 2016). The appropriate knowledge of medication side-effects helps the patients to optimize treatment regimens following their depression management goals. Accordingly, the patients could reduce their risk of weight gain, sexual dysfunction, profuse sweating, dry mouth, headache, dizziness, aggression, tremor, nausea, diarrhea, drowsiness, emotional numbness, and withdrawal complications of antidepressant medications.

- Systematic treatment of chronic diseases and their clinical complications is highly required to reduce the risk of depression manifestations. This is based on an elevated prevalence of depression among patients affected by chronic diseases like stroke, heart disease, cancer, and diabetes (Voinov, Richie, & Bailey, 2013).

- Maintenance of body mass index/weight management is highly required to reduce the risk of depression. This is because obesity profoundly deteriorates the mood and mental health of the affected individuals (Fuller et al., 2017).

- Modification in dietary patterns and eating habits helps in challenging the development of depression and anxiety. For example, the consumption of a Mediterranean diet helps in controlling depression manifestations (Gibson-Smith et al., 2019).

- Enhancement of social connectivity assists in overcoming higher levels of anxiety and depression. Social connectedness, social support, and positive interactions not only elevate the satisfaction level of the depressed people but also enhance their self-esteem and will power to a considerable extent (Seabrook, Kern, & Rickard, 2016).

- Avoidance of passive conversations/company of pessimistic people enhances the overall wellness and survival of depressed people. This is because the brain’s left hemisphere’s physiological activity reciprocates with optimistic beliefs, cheerful attitude, and self-esteem enhancement (Hecht, 2013). Similarly, optimistic views influence the right hemisphere’s neurophysiological processes.

- Maintenance of adequate sleep patterns potentially helps in controlling the clinical symptoms of major depressive disorder (Murphy & Peterson, 2015).

- Compliance with the prescribed treatment or pharmacotherapy for chronic illnesses is highly required to effectively reduce the global burden of depression (Gautam, Jain, Gauam, Vahia, & Grover, 2017).

- Avoidance of depression-causing medication is highly required to reduce the risk of dysthymia and associated mood depression (Gautam, Jain, Gauam, Vahia, & Grover, 2017).

- Stress reduction through meditation is a testified strategy to improve the emotional regulation processes in depressed people (Nima, Rosenberg, Archer, & Garcia, 2013).

- Standardization of daily routine and establishment of health care goals elevate self-discipline that potentially assists the individuals to control their anxiety and depression levels.

- Enhanced monitoring of pharmacotherapy/depression treatment outcomes helps in identifying the areas of depression management/prevention for chronically ill patients (Obbarius et al., 2017).

- Limited connectivity with social media helps to enhance the behavioral and emotional outcomes of depressed individuals. The restricted use of social media proves highly beneficial to improve the self-regulation skills of depressed people. Most importantly, reduced social media use helps to control the substance abuse/suicide tendencies, depression, and anxiety levels of students while improving their academic performance (Shensa, Sidani, Dew, Escobar-Viera, & Primack, 2018).

- Regular exercise assists in reducing the cardiovascular risk factors that potentially contribute to depressive symptoms (Murri et al., 2018). Daily walking for a duration of 30-40 minutes is highly recommended for depression/mood self-regulation.

- Enhancement of overall health-related quality of life (HR-QoL) is necessarily required to reduce the risk of depressive manifestations. The systematic use of cognitive behavior therapy is highly recommended to moderately enhance the HR-QoL of the individuals at high-risk of depression (Hofmann, Curtiss, Carpenter, & Kind, 2017).

References

Albert, P. R. (2015). Why is depression more prevalent in women? Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 40(4), 219-221. doi:10.1503/jpn.150205

American_Mental_Wellness_Association. (2020). Risk and Protective Factors . Retrieved from https://www.americanmentalwellness.org/prevention/risk-and-protective-factors/

Blackburn, T. P. (2019). Depressive disorders: Treatment failures and poor prognosis over the last 50 years. Pharmacology Research and Perspectives, 7(3). doi:10.1002/prp2.472

Brigitta, B. (2002). Pathophysiology of depression and mechanisms of treatment. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 4(1), 7-20. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3181668/

Cartwright, C., Gibson, K., Read, J., Cowan, O., & Dehar, T. (2016). Long-term antidepressant use: patient perspectives of benefits and adverse effects. Patient Preference and Adherence, 1401-1407. doi:10.2147/PPA.S110632

Chand, S. P., & Arif, H. (2020). Depression. In StatPearls. Treasure Island (Florida): StatPearls Publishing.

Conner, K. R., Pinquart, M., & Gamble, S. A. (2009). Meta-analysis of depression and substance use among individuals with alcohol use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 127-137. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2008.11.007

Fluharty, M., Taylor , A. E., Grabski, M., & Munafò, M. R. (2017). The Association of Cigarette Smoking With Depression and Anxiety: A Systematic Review. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 19(1), 3-13. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntw140

Fuller, N. R., Burns, J., Sainsbury, A., Horsfield , S., Luz, F. D., Zhang, S., . . . Caterson, I. D. (2017). Examining the Association Between Depression and Obesity During a Weight Management Programme. Clinical Obesity, 7(6), 354-359. doi:10.1111/cob.12208

Gautam, S., Jain, A., Gauam, M., Vahia , V. N., & Grover, S. (2017). Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of Depression. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 59(1), S34-S50. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.196973

Gibson-Smith, D., Bot, M., Brouwer, I. A., Visser, M., Giltay, E. J., & Pennix, B. W. (2019). Association of Food Groups With Depression and Anxiety Disorders. European Journal of Nutrition. doi:10.1007/s00394-019-01943-4

Hecht, D. (2013). The Neural Basis of Optimism and Pessimism. Experimental Neurobiology, 22(3), 173-199. doi:10.5607/en.2013.22.3.173

Hofmann, S. G., Curtiss, J., Carpenter, J. K., & Kind, S. (2017). Effect of Treatments for Depression on Quality of Life: A Meta-Analysis. Cognitive Behavior Therapy, 46(4), 265-286. doi:10.1080/16506073.2017.1304445

IQWiG. (2006). Depression: Overview. In InformedHealth.org. Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279285/

Kanter, J. W., Busch, A. M., Weeks, C. E., & Landes, S. J. (2008). The Nature of Clinical Depression: Symptoms, Syndromes, and Behavior Analysis. Behavior Analysis International, 31(1), 1-21. doi:10.1007/bf03392158

Mayo_Clinic. (2020). Depression (Major Depressive Disorder). Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20356013

McCarter, T. (2008). Depression Overview. American Health and Drug Benefits, 1(3), 44-51. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4115320/

Meng, X., Brunet, A., Turecki, G., Liu, A., D'Arcy, C., & Caron, J. (2017). Risk factor modifications and depression incidence: a 4-year longitudinal Canadian cohort of the Montreal Catchment Area Study. BMJ Open. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015156

Murphy, M., & Peterson, M. J. (2015). Sleep Disturbances in Depression. Sleep Medicine Clinics Journal, 10(1), 17-23. doi:10.1016/j.jsmc.2014.11.009

Murri, M. B., Ekkekakis, P., Ekkekakis, M., Zampogna, D., Zampogna, S., Capobianco, L., . . . Amore, M. (2018). Physical Exercise in Major Depression: Reducing the Mortality Gap While Improving Clinical Outcomes. Frontiers in Psychiatry. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00762

Nima, A. A., Rosenberg, P., Archer, T., & Garcia, D. (2013). Anxiety, Affect, Self-Esteem, and Stress: Mediation and Moderation Effects on Depression. PLoS One. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24039896-anxiety-affect-self-esteem-and-stress-mediation-and-moderation-effects-on-depression/

Obbarius, A., Maasakkers, L. V., Baer, L., Clark, D. M., Crocker, A. G., Beurs, E. D., . . . Rose, M. (2017). Standardization of health outcomes assessment for depression and anxiety: recommendations from the ICHOM Depression and Anxiety Working Group. Quality of Life Research, 26(12), 3211-3225. doi:10.1007/s11136-017-1659-5

Paykel, E. S. (2008). Basic concepts of depression. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 10(3), 279-289. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3181879/

Seabrook, E. M., Kern, M. L., & Rickard, N. S. (2016). Social Networking Sites, Depression, and Anxiety: A Systematic Review. MIR Mental Health, 3(4). doi:10.2196/mental.5842

Shensa, A., Sidani, J. E., Dew, M. A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., & Primack, B. A. (2018). Social Media Use and Depression and Anxiety Symptoms: A Cluster Analysis. American Journal of Health Behavior, 42(2), 116-128. doi:10.5993/AJHB.42.2.11

Voinov, B., Richie, W. D., & Bailey, R. K. (2013). Depression and Chronic Diseases: It Is Time for a Synergistic Mental Health and Primary Care Approach. The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders, 15(2). doi:10.4088/PCC.12r01468

This content is for informational purposes only and does not substitute for formal and individualized diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, prescription, and/or dietary advice from a licensed medical professional. Do not stop or alter your current course of treatment. If pregnant or nursing, consult with a qualified provider on an individual basis. Seek immediate help if you are experiencing a medical emergency.

© 2020 Dr Khalid Rahman