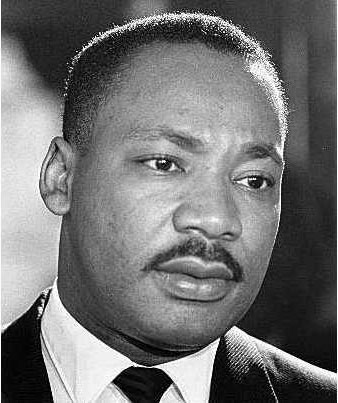

A Critique of Dr. Martin Luther King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail": Who is the Intended Audience?

Can’t Nobody Hold me Down, Oh No, I’ve Got to Keep on Movin’: A Critique of Martin Luther King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail"

Great Books for Reference

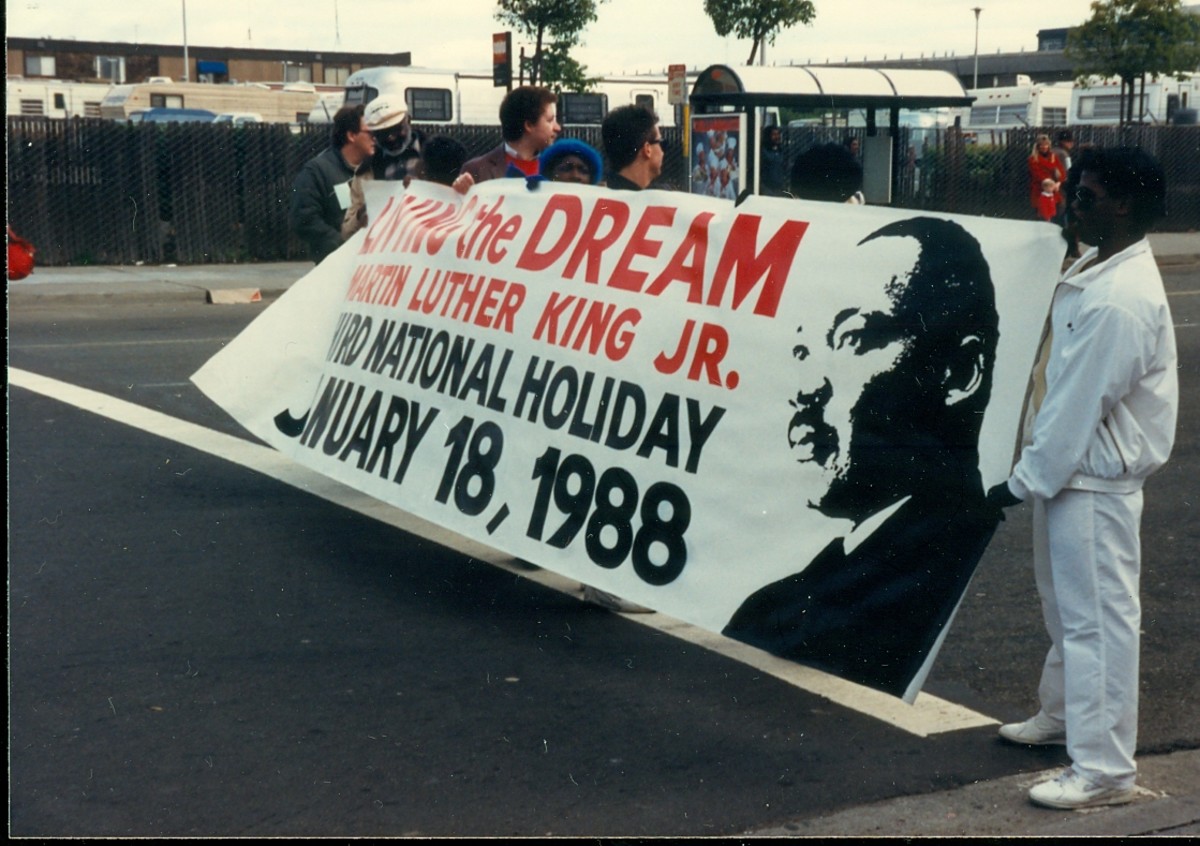

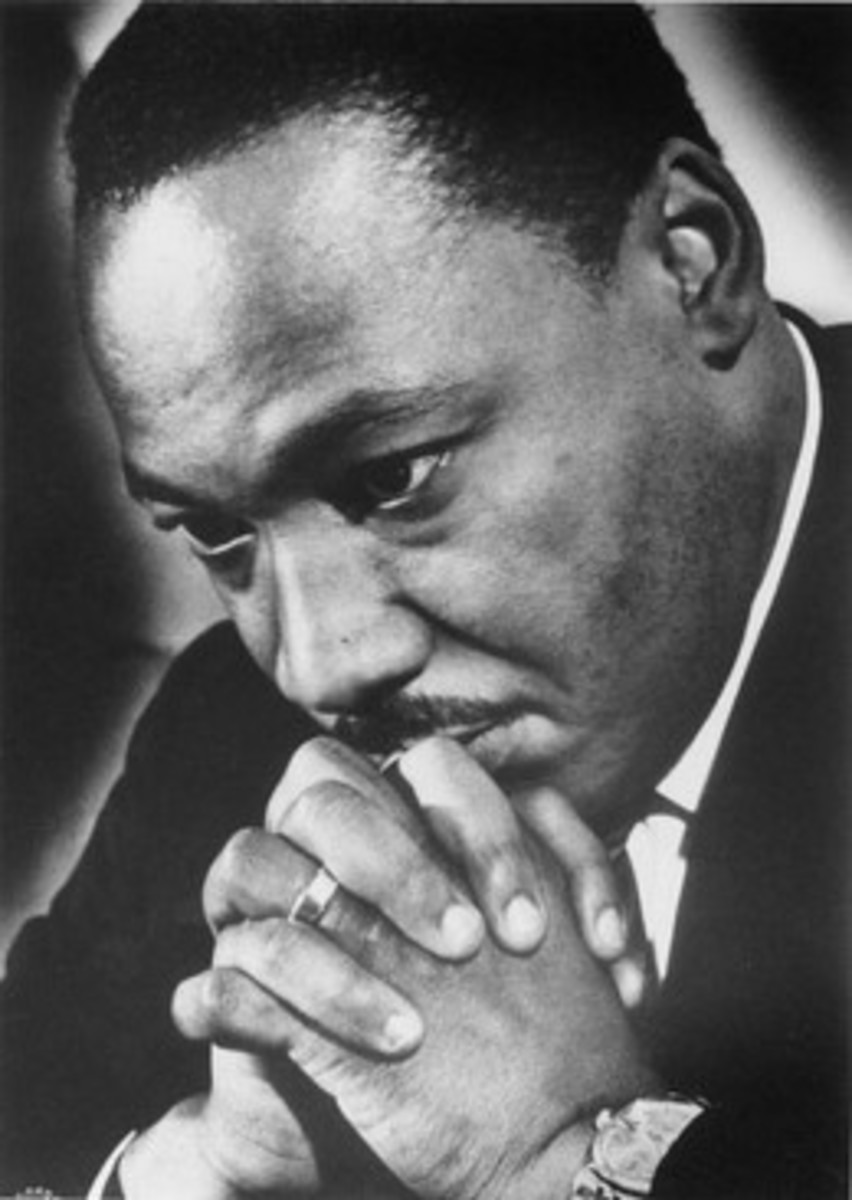

On Good Friday in 1963, 53 blacks, led by Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., marched into downtown Birmingham to protest the existing segregation laws. All were arrested. This caused the clergymen of this Southern town to compose a letter appealing to the black population to stop their demonstrations. This letter appeared in the Birmingham Newspaper. (Hornsby, 1986, pg. 38) In response, Martin Luther King Jr. drafted a document that would mark the turning point of the Civil Rights movement and provide enduring inspiration to the struggle for racial equality. Martin Luther King's “Letter from Birmingham Jail” strives to justify the desperate need for nonviolent direct action, the absolute immorality of unjust laws together with what a just law is, as well as, the increasing probability of the “Negro” resorting to extreme disorder and bloodshed, in addition to his utter disappointment with the Church who had not lived up to their responsibilities as Christians and even to those who have not lived up to the standards of a good moral people. King’s Letter has been critiqued in many ways and in this essay the ideas examined and these questions will be answered:

-

Who is the intended audience?

-

What theories provide insight in persuasion taking place?

This critique will focus on answering these two questions.

Who is the Intended Audience?

In the very first paragraph of Martin Luther King Jr’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail, we can see that King’s chief desire is to respond to the critiques of his activities in downtown Birmingham, Alabama. This is clearly seen even from the very first paragraph, “Seldom do I pause to answer criticism of my work and ideas… …But since I feel that you are men of genuine good will and that your criticisms are sincerely set forth, I want to try to answer your statement…” The men of good will are the eight Alabama clergymen who composed a letter admonishing King to be “more moderate in his demonstrations.” (Carter, 2002, pg. 8) While it is clear to see that King did have the Clergymen in mind when writing his letter, his audience was even broader than what a glance at the text would let on. Examining the eloquence of his speech in the easy to read style King so well establishes, other examiners have made comments: “King's prose exerts a strong attraction – it is magnetic; and it is this quality that primarily accounts for the “Letter’s” appeal beyond the audience of eight Southern clergymen to whom it is addressed, beyond them to the much broader audience of lay readers.” (Klein, 1981, pg. 31) Such a straight-forward, understandable letter which addresses many issues asides from the “untimely” and “unwise” accusations of several clergymen should beg the question of to whom was King also wishing to address?

This audience that Kings seeks to address and persuade are the one’s who make up the majority of people in the country: the common man, more specifically the “white man.” While the majority of the common black man is already a part of the movement, King needs the swaying ability of the “white man” who hold authority to achieve the goals in which he desires to meet. King refers to these persons as the “white moderate” and then shares his sense of failure with their lack of involvement:

I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro's great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen's Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to "order" than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: "I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action"; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man's freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a "more convenient season." Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection. (Hornsby, pg. 41)

Hopefully it can be seen after this paragraph King continues to address the lack of responsibility the “white moderate” has taken concerning the civil rights movement, nailing them and declaring them as an audience.

King then makes a focus from the “white moderate” to the “white church.” The rest of his letter then continues in his disappointment in the “white church” and how they have been inept, inactive and even apathetic concerning the major injustice done to the African Americans and how this should have been first on their plate of piety. Within this group King also includes the clergymen who have so spuriously written concerning their disagreement with the movements activities.

The religious are not the only crowd King wishes to address, but to leave religion as a preference to many, a preference many don’t prefer, he also addresses morality and justice, and appeals to those who hold themselves morally upstanding and just. This can be seen in some of the methods of persuasion King uses.

What Theories Provide Insight into the Methodic Persuasion Taking Place?

King draws heavily from the persuasive elements of beliefs, values and attitudes. More specifically much of Kings persuasive behavior can be classified in Azjein & Fishbein’s theory of planned behavior, described in Herbert W. Simons 2001 textbook, Persuasion in Society, as BVA theory. (Simons, pg. 29) In Azjen’s (1991) theory of planned behavior, “beliefs include judgements that a given object possesses certain attributes. Values include judgments of the worth of these perceived attributes. (Simons, pg. 28) Understanding this, the primary beliefs King chooses to engage are those of the religious sort and the primary values he chooses to uphold are those of the Judeo-Christian moral sense.

The example of King’s appeal to the white congregation:

…despite these notable exceptions, I must honestly reiterate that I have been disappointed with the church. I do not say this as one of those negative critics who can always find something wrong with the church. I say this as a minister of the gospel, who loves the church; who was nurtured in its bosom; who has been sustained by its spiritual blessings and who will remain true to it as long as the cord of life shall lengthen. (Hornsby, pg. 42)

Seeing this, Mott (1960) describes the use King has for this idea, ‘King is not simply lending "respectability" to his philosophy by citing revered precedents; he is employing sound methods of persuasive rhetoric by arguing within the frame of reference familiar to a broad audience.’ (Mott, pg. 417) That familiar broad audience being the religious, particularly the Christians, help show the goal in which King was aiming. To allude to the scriptures and the call of being a minister helps an audience find commonality with their faith and then helps cause a dissidence in their minds through the idea that King is a credible minister and doing work to earn civil rights for all, so should all other Christians.

King also worked to show how civil disobedience will not cause dissidence within the Christian by alluding to more scriptures, particularly those of Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego and great Christian martyrs.

After engaging the beliefs of the Christian, King also pulls a double whammy by then engaging the values of all.

To a degree, academic freedom is a reality today because Socrates practiced civil disobedience. In our own nation, the Boston Tea Party represented a massive act of civil disobedience.

We should never forget that everything Adolf Hitler did in Germany was "legal" and everything the Hungarian freedom fighters did in Hungary was "illegal." It was "illegal" to aid and comfort a Jew in Hitler's Germany.

King tugged at the heartstrings of our nation by including the concept of freedom in this paragraph. Doing so King does more than draw in the Christian, but he is able to find common ground with the patriot, the lover’s of justice and those who understand the need for fairness. With this swoop King also includes our country’s understanding of academic freedom and importance. This notion would help find the rapport needed to include those who teach, those who learn and those who also find education to be significance. With these examples he shows that once these things were not so freely given, but it took rebellion of some sort to receive the God given rights so declared by our country.

One last emotion King appeals to here is fear. Fear as a result of injustice done by man taking away the freedoms of men through unfair law. King then even causes a reader to question whether a law is truly lawful, good and right or not. King awakens a skepticism in the mind of the observer so they would then question the morality and truth of what they have been told to obey.

Conclusion

Though it is understood from a prima facie the reading that the audience is eight clergymen from Alabama, reading and understanding the persuasive methods employed by King can help a reader understand there is a greater audience in which he attempted to reach from the small jail cell in Birmingham. The success of this can be observed through the later rallies and marches performed by the civil rights movement, particularly that of MLK’s leadership. Success was found in the streets, in the homes of average Americans and most significantly in the courtrooms of congress. Though these truths may be self-evident, that all men are created equal, it may take boldness and courage to make everyone see that since these are God-given and not man-given, that no man can take them away from another.

Citations

Hornsby, A. (1986). Martin Luther King Jr. “Letter from a Birmingham jail”. The Journal of Negro History, 71(4), 38-44. Retrieved December 3, 2008 from JSTOR database.

Klein, M. (1981). The other beauty of Martin Luther King, Jr.'s "Letter from Birmingham Jail". College Composition and Communication, 31(1), 30-37. Retrieved December 3, 2008, from JSTOR database.

Mott, W.T. (1975). The rhetoric of Martin Luther King, Jr.: Letter from Birmingham jail. Phylon, 36(4), 411-421. Retrieved December 3, 2008, from JSTOR database.

Simons, H.W., Morreale, J., & Gronbeck, B. (2001). Persuasion in society. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc.

Tiefenbrun, S. (1992). Semiotics and Martin Luther King's "Letter from Birmingham jail". Cardozo Studies in Law and Literature, 4(2), 255-287. Retrieved December 3, 2008 from JSTOR database.