The History and Meaning(s) of Halloween

Here is a more healthy attitude toward death:

Things We Can Learn from those Pagans

Halloween is an ancient, often misunderstood holiday that has evolved and been altered in a wide variety of ways over the course of more than one thousand years. Today, some people apparently think that it is a satanic day when the devil and his legions (both in human and demon form) are running amok. Others simply see it as a day to get dressed up, gorge oneself on candy - or, if you are an “adult,” alcohol - and figure out some way to get scared out of your wits. But amazingly, in spite of the ways that this holiday has changed in modern times, you can still see in our current traditions remnants of its ancient roots.

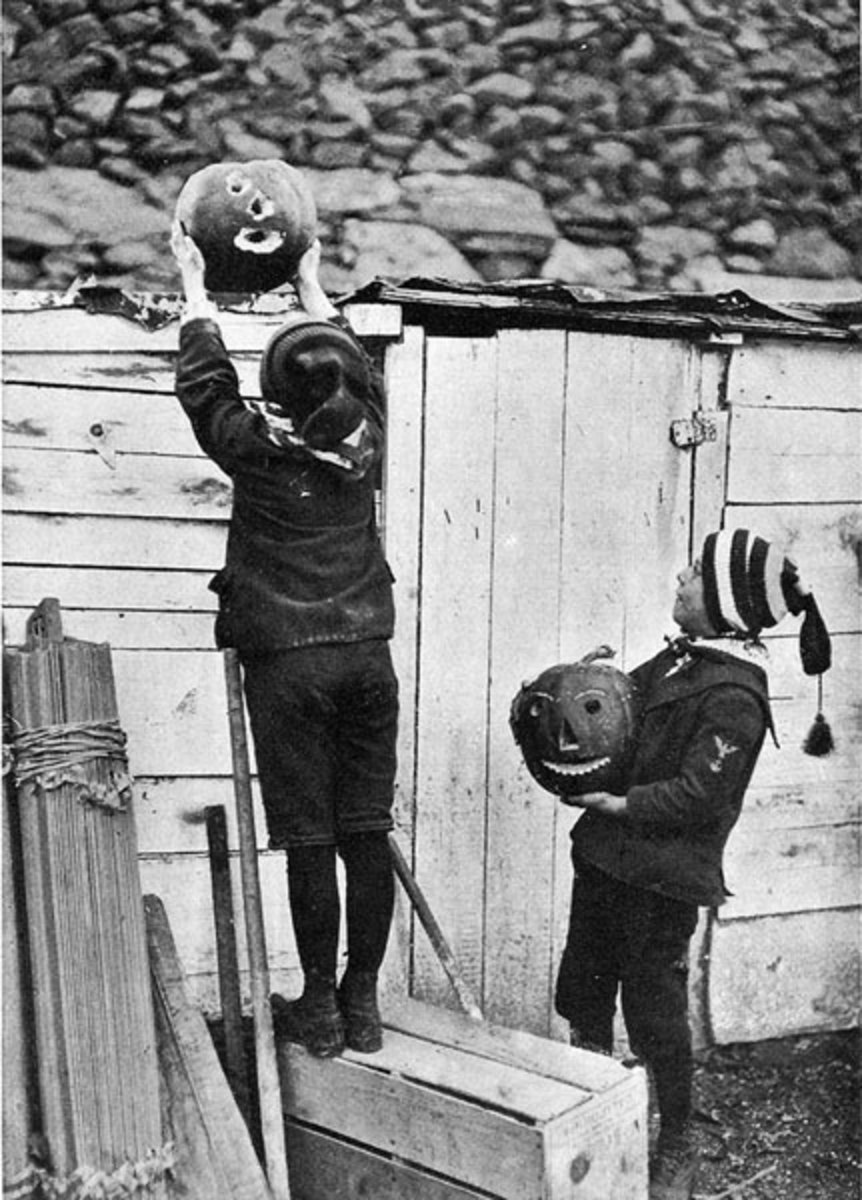

As best historians can tell, Halloween originated from the ancient Celtic holiday of Samhain, which was essentially a harvest festival. At this time of year that people were harvesting crops in preparation for the winter, Samhain was believed to be a day when the barriers between the realms of the living and dead would break down somewhat, and spirits could temporarily enter this world to either do mischief or to stop by and visit relatives. In some of the various holiday customs practiced centuries ago in Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, you can see the origins of many of our current Halloween traditions: images of scary ghosts and skeletons, dressing up in costumes, and “trick or treating.” In some places centuries ago, people dressed up in costumes in order to disguise themselves from spirits. In others, people dressed up in order to imitate the spirits, sometimes going from house to house in order to pray for people’s dead ancestors or to threaten mischief if they were not appeased. So in the places where young people dressed up as mischievous spirits, they would perform some kind of a prank, or “trick,” on the houses where they were not given any “treats.” (Although the term “trick or treat” does not appear in any literature until relatively modern times.) In fact, as the holiday began to be widely practiced in the United States by the late 19th - early 20th centuries (being brought here by Irish and Scottish immigrants), it would eventually become known as a day when troublemaking teenagers went around committing mild acts of vandalism. As a kid, I still remember broken pumpkins lining the streets on the day after Halloween.

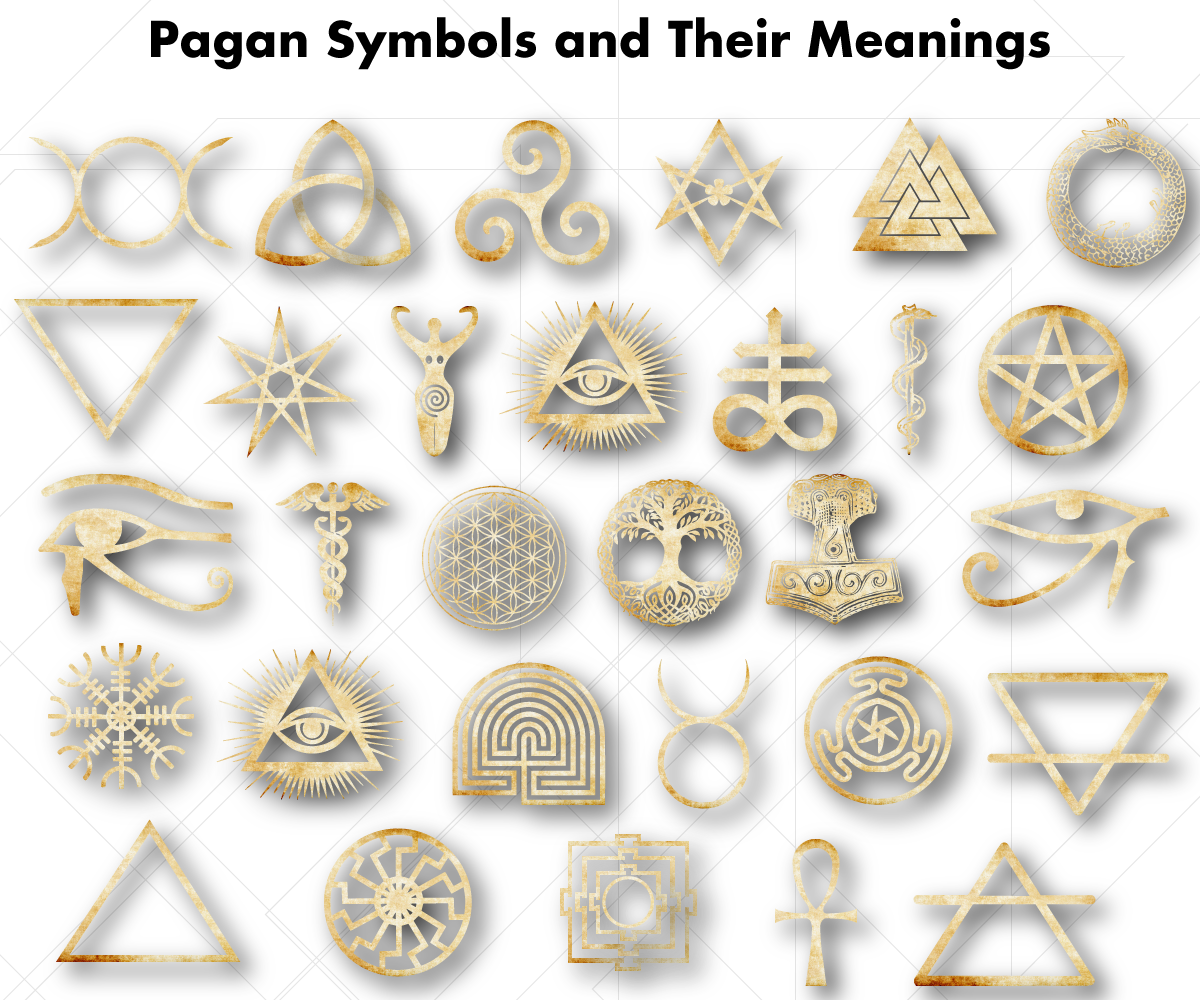

The term Halloween, however, has Christian rather than pagan origins. It is an abbreviation of the term “All Hallows Eve” because on the Catholic Christian calendar, it is the day before All Saints Day. Apparently, the Church decided in the 10th century to overlay both the day and the meaning of this pagan harvest festival with Christian imagery. So instead of interacting with pagan spirits, Christians would reflect on the saints of the past. It is similar to what happened centuries ago with Christmas and Easter. The date of Jesus’s birth, after all, is not given in any of the gospels, so the church eventually placed it at the same time as the various pagan holidays that took place near the winter solstice, with the pre-Christian symbols of trees and lights being co-opted as well. The timing of Easter, on the other hand, is more closely specified in the Bible, but associating the holiday with pagan fertility symbols like rabbits and eggs came along much later, coinciding with the holiday falling in the spring. (Even the name Easter seems to have pagan origins.) So if the Church was unable to snuff out ancient pagan practices when it converted these populations to Christianity, the next best thing was to Christianize the pagan imagery, and hopefully over time, the pagan origins and meanings would fade away.

On many levels, I am grateful that I do not live in the pre-Christian, Celtic societies where Samhain was first being celebrated. But in spite of the many advantages of living in modern times, a holiday like Halloween reminds me of a couple of important things that we modern people have largely lost. For one thing, these pagan societies were far more in touch with the natural world than we modern, technology-inundated folk. They were far more dependent on and aware of the rhythms of nature, and they were continually aware of the simple fact that death could be right around the corner. This awareness of the constant possibility of death was particularly acute during the fall harvest as people stored away their food in preparation for a long winter. It is no wonder, then, that this day when the dead and living came into closer interaction took place at this especially scary time of year. Facing death head on just before the winter begins, I imagine, could be a very healthy coping mechanism.

In this modern society where we spend much of our time in artificially controlled environments, where food magically appears in grocery stores, and where a wide variety of plastic surgery options are available to wipe away even the appearance of age, we are not very skilled at dealing with death. We operate under the assumption that we are going to live for a long time, and when people do eventually get very old, we have a tendency to stick them into rest homes where we don’t have to look at them too often. And with modern cemeteries in particular, we often stick the bodies in remote places where we don’t have to see the tombstones. The United States in particular may be one of the most inept nations when it comes to dealing with death, which may help explain why we lead the world by far in medical spending, a significant percentage of which is spent on people during their last month of life. Americans seem to struggle with letting go, often being willing to do whatever it takes to eke out for their loved ones just a few more (often painful) days.

And yet Halloween, a day in which ancient peoples faced their fears of death head on, has become more popular in the United States as time has passed. But today, dressing up is just for fun, “trick or treating” is a means of ingesting mass quantities of sugar, and we get scared for the sake of getting scared. This enjoyment of the superficial imagery of the holiday demonstrates another key difference between ourselves and our pagan ancestors: we have lost our sense of metaphor. We live in a time where people often argue about the literal truth or falsehood of our myths, and in doing this, we have lost touch with the profound truths and healing powers of our traditions.

I have mixed feelings about my culture’s big holidays. On the one hand, I find it both hilarious and annoying that they often degenerate into nothing more than orgies of shopping and candy ingestion. I find it equally pathetic that people know so little about the histories of the days that they celebrate and seem to lack any desire to learn even the basics. But on the other hand, when I reflect on the ancient, complex, multicultural origins of some of these traditions, I am in awe of their staying power. Being a firm believer in the concept of cultural evolution, I recognize that traditions that stand the test of time have been able to do so because they manage to keep filling some basic human needs. Sure, we have somewhat sucked the life out the trees, jack ‘o lanterns, bunnies, eggs, lights, costumes, and ghosts, and yet the images still endure. Apparently, in spite of centuries of effort to snuff them out, we still have a lot to learn from those pagans.