Halloween: More than Celtic Samhain! Day of the Dead Across Pagan Europe

Halloween: Is there more to the story?

Standard historians typically describe Halloween as an autumn festival rooted in the ancient Celtic celebration of Samhain. According to the familiar account, Gaelic and Scotch‑Irish settlers brought their ghost lore and mischief‑making traditions to America in the 19th century. From there, Halloween gradually spread through American culture until it became deeply embedded in the national consciousness. Before long, it was embraced by the majority of Americans and turned into a beloved annual holiday.

Over time, Halloween became so closely associated with American culture that many in Britain seemed to forget that it had originated in the Isles. I have heard countless Britons describe Halloween as an American invention—at least until it drifted back across the Atlantic, re‑emerging in modern, Americanized form.

But what if there’s more to the story?

More Halloween Lore

Awakening an Ancestral Memory

The 19th century brought waves of immigrants from many parts of Europe that had been absent from the early American colonies. Settlers from Central, Eastern, and Southern Europe arrived in great numbers, bringing their own folk traditions and spiritual customs. The United States already had, and continued to receive, settlers from Britain and the Germanic/Scandinavian world.

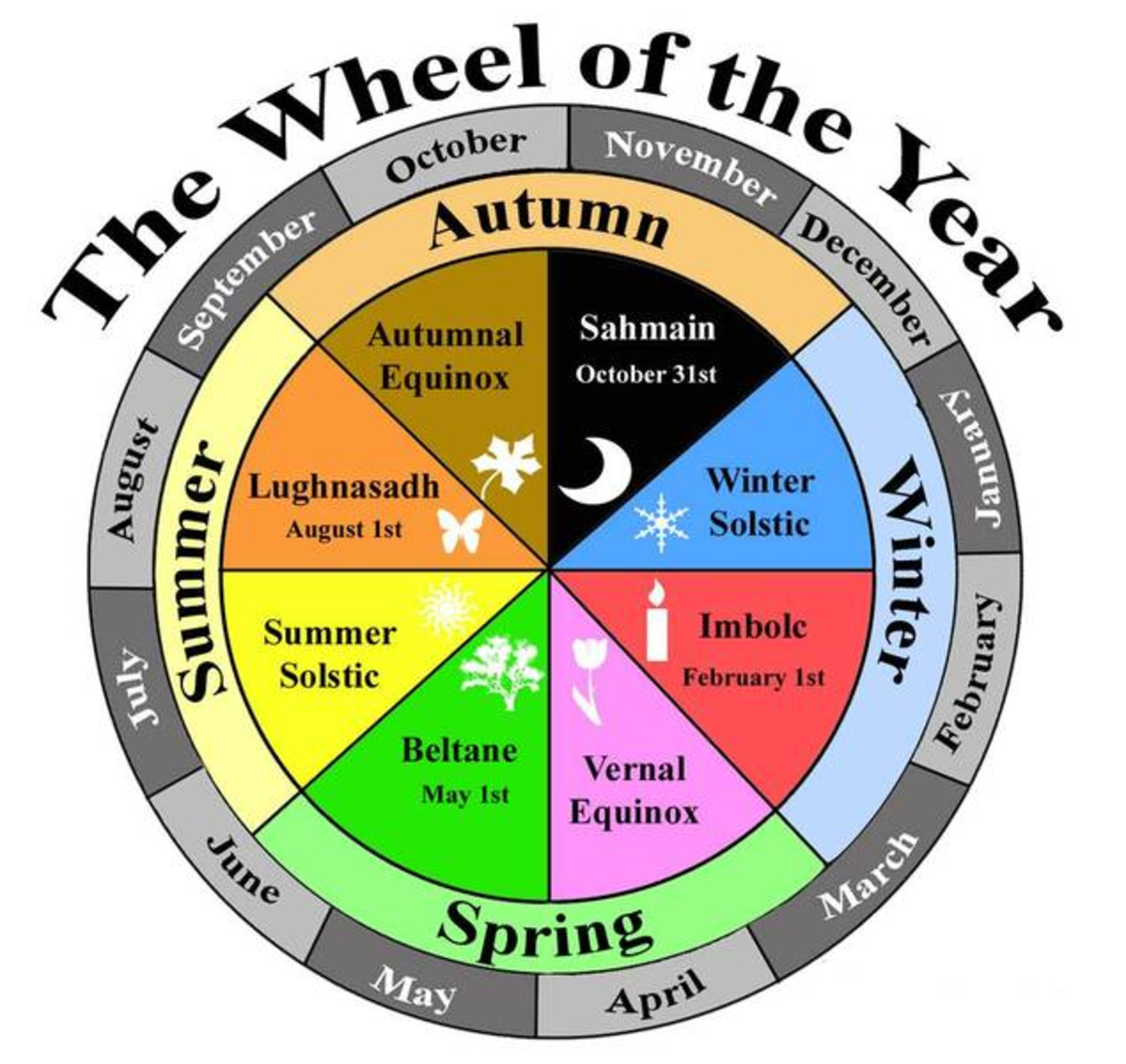

Why did all these non‑Gaelic Americans—both newcomers and founding stock—embrace Halloween with such enthusiasm? Perhaps Gaelic immigrants, by sharing their version of an ancient European folk festival, awakened something deeper in the collective European memory. When we explore the indigenous spiritual traditions of pre‑Christian Europe, we find celebrations strikingly similar to Halloween across nearly every region of the continent. Most occurred at the end of October or early November, marking a sacred time connected to the dead and the natural cycle of the year.

The Christian Transformation

The very name Halloween is a contraction of All Hallows’ Eve, the night before All Saints’ Day—ostensibly a Catholic holiday. Historians tell us that the early Church established this feast in the 7th century AD, but what is often omitted is that it appropriated and repurposed ancient European festivals long predating Christianity.

The Church’s official aim was to honor the departed before celebrating all the Christian saints collectively. Yet this was, in essence, a rebranding of existing pagan observances and served a deeper purpose: redirecting folk devotion and communal loyalty away from kin‑based ancestral traditions toward ecclesiastical authority and a universalist worldview.

In earlier pagan festivals, remembrance centered on family lineages and direct ancestors. The Church shifted this focus to saints and martyrs, creating a universalized—catholic, literally “all‑encompassing”—faith designed to replace tribal and ethnic loyalties with spiritual allegiance to the institution itself. In doing so, the Church severed the intimate bond between faith and family that had defined European spirituality for millennia. What began as a localized festival of the ancestors became a tool for social engineering aimed at spiritual centralization and cultural control.

Pagan Custom, Christian Overlay

A Common Sacred Heritage Across Europe

Just as East Asian cultures share clear continuities despite linguistic and regional differences, pre‑Christian Europe too possessed a shared cultural and spiritual core. Ancestor veneration, seasonal rites, and festivals of the dead were present in nearly every European tradition.

As Christianity conquered Europe, often violently, its longevity was partly due to its absorption of these older customs, which allowed familiar forms to remain while transforming their meaning. Yet this also obscured the memory of Europe’s own native faiths. Over centuries, Christianity came to be seen as the natural religion of Europe—by both Europeans themselves and the wider world. In reality, it had overwritten a vast and diverse network of indigenous spiritual practices united by reverence for nature, kinship, and the continuity of life.

When we speak of Halloween’s origins as the Celtic festival of Samhain, we must remember that it represents only one branch of a much larger European tree. Across Europe, our ancestors shared a rich, vibrant, and beautiful faith intertwined with the natural world and sustained by ancestral reverence. This animistic worldview recognized spirit as the living force within all beings and the elements themselves. Death, in this understanding, was not an end but a transformation within the eternal cycle of existence.

Just as the seasons turn through the rhythm of the year, so too did life and death mirror an unbroken continuum. The dead were believed to return through their descendants, nurturing and guiding the living. Of all spirits one might call upon for protection, none were more personally invested than those of one’s own bloodline. No wonder, then, that ancestral remembrance and kinship held such significance in the seasonal calendars of Europe’s native faiths.

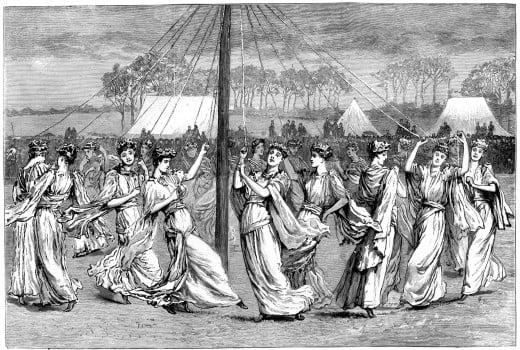

The Maypole - A Widespread Euro-Pagan Custom

European Parallels to Halloween

While American Halloween descends most directly from Celtic Samhain, similar festivals appeared throughout Europe. Each ethnic group honored its dead in distinct ways yet shared the same spiritual essence. Some notable examples include:

-

Kala Goañv (Brittany)

-

Dziady (Slavic lands)

-

Álfablót (Scandinavia)

-

Kekri (Finland)

-

Vėlinės (Lithuania)

-

Veļu Laiks (Latvia)

-

Feralia (Ancient Rome)

Each festival marked the time when the veil between the worlds grew thin, and offerings were made to the ancestors who continued to live among their descendants.

A Shared Pagan Core

Though languages, landscapes, and aesthetics differed, a continuous thread bound all European pagan traditions—a reverence for the dead, an understanding of cyclical renewal, and a deep sense of sacred belonging to one’s household and land.

1. The Spirits of the Dead Live Among Us

Autumn was known as a liminal season when the boundary between the seen and unseen worlds thinned. The departed were believed to traverse this veil to commune with the living. Across Europe, families lit bonfires to guide and warm ancestral spirits, leaving food offerings so that their essence might be nourished. These acts of remembrance sustained the invisible bonds between generations and reaffirmed the unity of the living and the dead.

2. Life as a Never‑Ending Cycle

Many historians identify Samhain as the Celtic New Year, yet it also represented the dying close of the cycle. The Roman historian Tacitus observed that the Germanic tribes began each new day at sundown—a reflection of their view that death precedes rebirth. The European autumn festivals embraced this same understanding: as crops were harvested and the earth grew still, people contemplated the eternal rhythm of decay and renewal. Just as green shoots emerge each spring, so too does ancestral spirit return through the living. In giving thanks for the harvest, our forebears also honored the presence of their ancestors and prepared to face the long dark of winter with faith in the sun’s inevitable return.

3. The Sacred Household and Lineage

Unlike Catholic rites held publicly in churches, the ancestral devotions of old Europe were private, taking place within the home or at family burial grounds. The household itself was believed to possess a spirit—a guardian presence linking the living to their forebears. The home was viewed as a sacred womb of renewal, sheltering the lineage and channeling ancestral protection to future generations. The dead were not gone but transformed, continuing their guardianship within the family and reborn through its descendants.

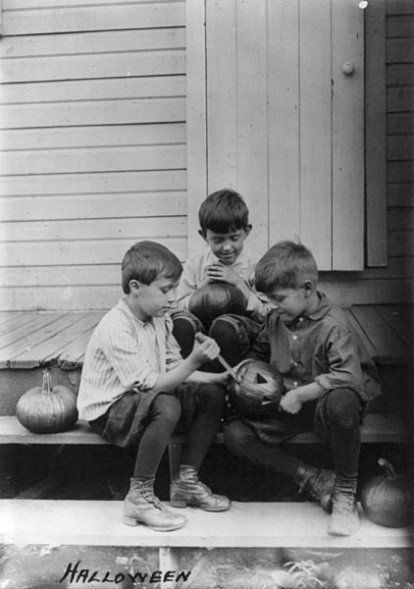

In Remembrance

Halloween’s popular commercial image—as a night of costumes, ghosts, and pumpkins—conceals its profound ancestral roots. What resonates in this ancient festival is not mere superstition but a remembrance of who we are and where we come from. Beneath centuries of Christianization and modern commercialization lies a timeless truth: that life, death, and rebirth are woven into one sacred continuum, and that our connection to those who came before us is neither broken nor forgotten.

Across Europe and throughout the New World diaspora, as Halloween returns each autumn, it stirs something primal—a faint echo of remembrance. Beneath the masks and flickering candles, we honor the same enduring mystery that our forebears once did: the living spirit that moves through all things, forever renewed.

Ancestor Altar Ideas

© 2025 Carolyn Emerick