The Definitive Voice of 19th Century American Poetry

“We fathom you not—we love you—there is perfection in you also, You furnish your parts towards eternity, Great or small, you furnish your parts toward the soul” –Walt Whitman, “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry”

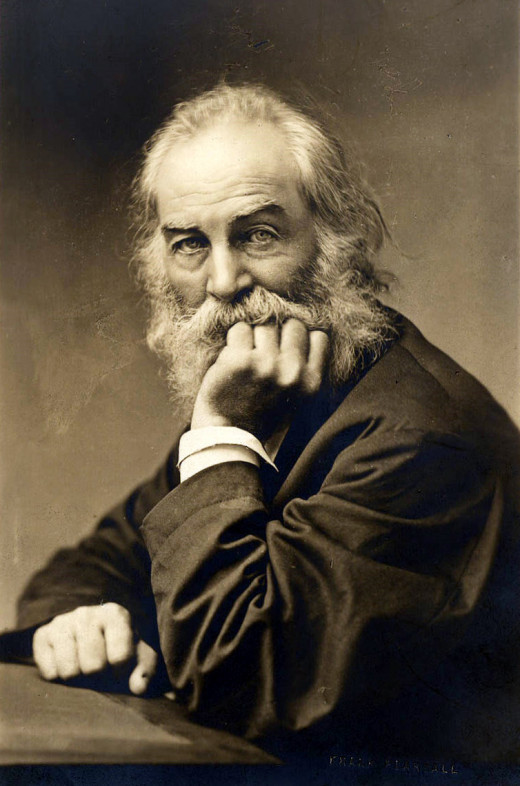

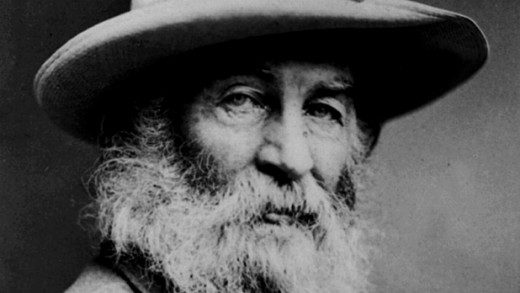

At the turn of the 18th century, the western literature experienced a shift from the logocentric Enlightenment philosophies towards the subjective and imaginative philosophies of romanticism and transcendentalism. Despite the harsh criticisms of the Victorian literary critics and writers that emphasized realism over the romantic phantastic images, romantic and transcendental elements continued to pervade 19th century works and still play a major role in literature today, especially the emphasis on individual perspective and artistic originality (Murfin, Ray, pg. 418). Furthermore, the most prominent themes of 19th century literature focus on the core dynamics of both romantic and transcendental beliefs: writers valued imagination and emotion as highly as reason and intellect; believed that humans are naturally good; felt that nature is the source of sublime feeling, divine inspiration, and even moral action; celebrated the individual rather than social order and, indeed, critiqued oppressive, class-based political regimes and social forms; and rejected many of the artistic rules, forms, and conventions associated with classicism and neoclassicism, considering them to be aesthetic forms of repression or, at least, unnecessary constrictions detrimental to the individual artist’s calling (Murfin, Ray, pg. 422). No poet from the 19th century exemplified the core beliefs of romanticism and transcendentalism, which characterize the literary trends of the 19th century’s values, tastes, and concerns better than the American poet, Walt Whitman.

Walt Whitman

Whitman’s poetry collection “Leaves of Grass,” which transmuted multiple times throughout several editions during his lifetime, was one of the most popular, thought provoking, and revolutionary works of literature during the 19th century. Both the form and content of the poems in “Leaves of Grass” were groundbreaking; Whitman’s sprawling lines and cataloguing technique, as well as his belief that poetry should include the lowly, the profane, even obscene, have had enormous influence. Ultimately, Whitman’s innovative intention was to create a purely American literary tradition, one “Proportionate to our continent, with its powerful races of men, its tremendous historic events, its great oceans, its mountains, and its illimitable prairies” (Atwood, Ousby, pg. 572).

Socio-Political Consciousness

Besides Whitman’s radical approach to verse, which highlighted colloquial language and descriptions of everyday American life, Whitman’s poetry responded to the major concerns surrounding 19th century American politics including the horrors of the civil war, the corruption of Washington during the Reconstruction era, and the reaffirmations of democratic principles (Atwood, Ousby, pg. 1070). Furthermore, Whitman embraced and exemplified the core philosophical trends of the 19th century in the romantic and transcendental movements, which extoll the individual rather than ritualistic spiritual living, the virtues of nature and manual labor, and the need for intellectual stimulation. Furthermore, these new movements encouraged self-reliance and self-trust to fulfill human potential, often allying themselves with such causes as women’s suffrage and abolitionism (Murfin, Ray, pg. 488).

"Crossing Brooklyn Ferry"

Of Whitman’s prolific poetry collection spanning over 400 poems in “Leaves of Grass,” the one poem that truly stands out as the most definitive poetical voice of 19th century is his “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry.” Whitman’s poetical voice accurately resembles Ralph Waldo Emerson’s ideal poet postulated in his critical explication, “The Poet” in “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry.” Emerson makes it clear that the poet must report passionately on personal experiences that will stimulate readers embarked on their own spiritual and intellectual journeys: all experience is meaningful; no “sensual fact” lack spiritual significance (Cain et al., pg. 719). Essentially, Whitman describes how these fragments of divinity dwell in every living and inanimate object consistent with transcendentalism in lines 130-132, “We fathom you not—we love you—there is perfection in you also,/You furnish your parts towards eternity,/ Great or small, you furnish your parts toward the soul” (Ferguson et al., pg. 969).

Matching Form with Content

Furthermore, Whitman’s fascination with everyday life, especially nature, is evident throughout most of the poem such as in lines as “Flood-tide below me! I see you face to face!” and “Flow on, river! Flow with the flood-tide, and ebb with the ebb-tide” (Ferguson et al., pgs. 967-968). As Whitman describes the river, not only is he referring to the eternal cycles of nature and the commonness of human experience, he is also interweaving his poetical content from descriptions of society, the movements of earthly bodies and beasts, and the higher concepts of past and future, love, and sensuality; Whitman’s flow of verse functions to mend each element of his content as it ebbs and flows from and into the coming lines of verse.

Thus, not only is Whitman weaving a quilt of content that connects all the fragments of divinity, but he also emphasizes the future and what is to come; he constantly reminds of us of the ebb tide and eternal cycles of nature and how human experience mimics such cycles in lines 20 “Its avails not, time nor place—distance avails not,” 54, “What is it then between us?” and 86, “Closer yet I approach you” (Ferguson et al., pgs. 967-968). This progress towards the future also is reflected in the structure of Whitman’s verse as readers draw ever near closer towards Whitman’s powerful conclusion.

Transcendentalism

Furthermore, Whitman’s content exemplifies a key attribute of 19th century transcendentalism that the poet’s often-expressed ambition was to achieve a vivid perception of the divine as it operates in common life, an awareness seen as leading at once to personal cultivation and to a sense of history as an at least potentially progressive movement (Atwood, Ousby, pg. 1001). Thus, Whitman’s appeal towards the future functions in a duality between establishing an American literary consciousness and a universal collective consciousness; creating poetry that was both unique and common: “expressing what is oft thought but n’er so well expressed.” Thus, Whitman highlights the valorization of personal experience by appealing to a deepening sense of history: an essential trait of romanticism. Paradoxically, he creates history by reflecting on the future, which Whitman claims is always there in the lines “I consider’d long and seriously before you were born” and “Who knows, for all the distance, but I am as good looking at you now,/for all you cannot see me?” (Ferguson et al., pg. 968). Again, Whitman draws on the 19th century transcendentalist philosophy that each human being is innately divine, that God’s essence lies within all individuals even before they are born (Murfin, Ray, pg. 488).

Poetry as Self-Expression and a Beckoning to Society

Clearly Whitman’s “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” functions as an expression of his personal experiences in fervent livelihood; “to endeavor to hearken to the voice within, to the inner light” (Cain et al., pg. 720). Whitman is Emerson’s ideal poet: one who is alert to the meanings that saturate all of existence and write passionately alive (Cain et al., pg. 719). Even so, Whitman’s revolutionary verse was also a power working for social and moral transformation—the chief influence in civilizing community according to the Romantic poet, Percy Shelley (Cain et al., pg. 698). Not only does Whitman’s gentle didacticism inform readers of transcendentalism, which he must have been an ardent advocate, and thus believed its beliefs had the power to change corruption in society and warped political views, but he also revels in his own spiritual and intellectual journey and understanding of the interconnectedness of all things and phenomena.

Summary and Concluding Thoughts

Whitman is the definitive poet of the 19th century. He flourished and changed the face of American literature and still is a major influence today. He exemplified the major philosophical trends of the 19th century and explicitly presented those romantic and transcendental ideas in his verse. Furthermore, his intentions for writing his poetry accurately reflected those prevalent belief systems, and they functioned in accordance as well. Ultimately, one of his most popular poems from his “Leaves of Grass” titled “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” is arguably the most representative poem of the 19th century. It strikes a perfect harmony between romantic and transcendental ideas, society and nature, present and future, unique and common, the living and the inanimate, and, of course, the divinity of existence and the interconnectedness of all things and phenomena.

References

Atwood, M., Ousby, I. (1988). The cambridge guide to literature in english (1st ed.) New York, NY: Cambridge University Press & The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited.

Cain, W., Finke L., Johnson B., Leitch V., McGowan J., & Williams J.J.(2001) The norton anthology: Theory and criticism (1st ed.) New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Ferguson, M., Salter, M. J., & Stallworthy, J. (Eds.). (2005). The Norton anthology of poetry (5th ed.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Murfin R., Ray S. (2003). The bedford glossary of critical and literary terms. Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s.