A Guide to Relative Pronouns: Which, That, and Who(m)

Relative Pronouns

English was not brilliant crafted by a master builder who created each word to have a specific purpose without overlap. Furthermore, since grammatical rules still maintained by pundits are often ignored in everyday usage, the language continues to evolve despite grammarians’ exhortations. Relative pronouns are a good example of this messiness.

Relative pronouns modify the noun mentioned in the main clause. They connect the dependent (relative) clause to the main clause in the sentence. The most common relative pronouns are who, that and which.

Other relative pronouns: whom, whose, what, whoever, whomever, whichever, and whatever.

Who

Persons, not Things

Who belongs strictly to persons, not things. If an animal has a name, who can be used.

Possessive Forms

Possessives of who: whose and of whom

Non-defining Relative Pronoun

Abiding strictly to grammatical rules, who is a non-defining (aka nonrestrictive) relative pronoun.*

Rather than identify or define the antecedent noun, non-defining relative clauses add information and supplement the main clause. The main and non-defining clauses comprise independent statements that could be separated into two sentences.

- Example:

Jeff, who has not yet arrived, is bringing gifts.

- Separated into independent sentences:

Jeff is bringing gifts (main clause). He has not arrived yet (non-defining clause).

Non-defining clauses are parenthetic and must be set off by commas: prior to the relative pronoun and at the end of the clause (unless the clause comes at the end of the sentence).

Example 1

My aunt Kathy, who enjoys reading fine literature, teaches English.

- The first part (“My aunt Kathy”) is defining and therefore should not be set off by commas. I may have multiple aunts, so the inclusion of the name (“Kathy”) defines or limits the noun.

- The non-defining relative clause (“who enjoys reading fine literature”) is parenthetic and therefore set off by commas.

- This could be written as two sentences:

My aunt Kathy teaches English. She enjoys reading fine literature.

Example 2

My youngest sister, Julia, studies Architecture at university.

- Specifying that the noun is my youngest sister, not just any sister, is sufficiently defining without the inclusion of more information. Therefore, the name (“Julia”) adds information, making it parenthetic and requiring the use of commas.

- Implied in the non-defining clause is the phrase, “Whose name is.”

- This could be written as two sentences:

My youngest sister’s name is Julia. She studies Architecture at university.

*While who is often used as a defining pronoun, proper grammar dictates that it be restricted to non-defining cases, and that that be used to denote persons when a defining pronoun is needed. Fowler is insistent that it be used only for non-defining cases, acknowledging only begrudgingly its misuse, while Strunk and White use it in both defining and non-defining contexts without conceding a controversy. I am inclined to side with Strunk. Nonetheless, pending its official establishment as purely a non-defining relative pronoun, who will continue to regularly be used in both defining and non-defining contexts. If you use it as a defining pronoun, please remember the following:

Preceding the pronoun with a comma signifies a separation between the main clause and a non-defining clause. A comma should not be used when the pronoun initiates a defining clause.

Example:

Viewers of Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction, who also saw Jackie Brown, generally preferred the former.

- The use of a comma prior to the relative pronoun (“who”) suggests that everyone who saw Pulp Fiction also saw Jackie Brown.

- This should be changed to:

Viewers of Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction who also saw Jackie Brown generally preferred the former.

Who should refer to particular persons, while that refers to generic persons (more on this below).

References Used for this Hub

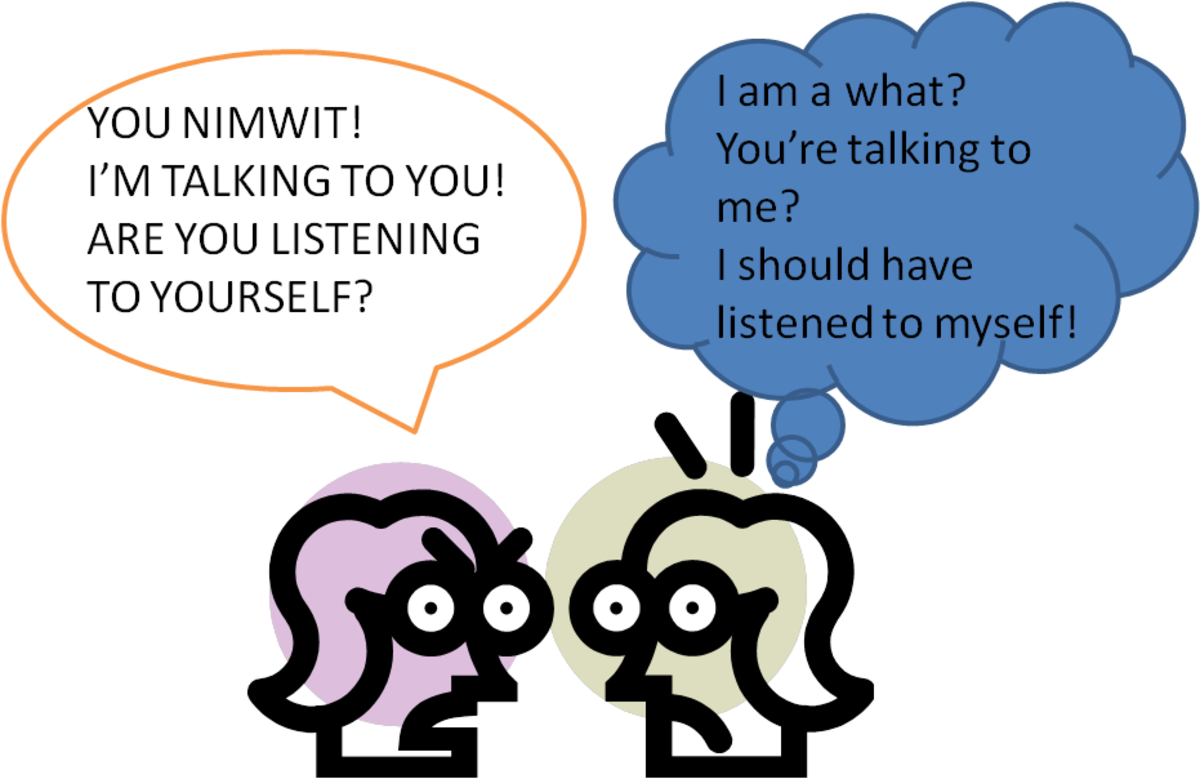

Who and Whom

Who refers to the subject (does the action). Whom refers to the object (receives the action). To my dismay, I hear who more often than whom for objective cases. The colloquialism even appears in respected print sources. I am sympathetic, to some extent; I didn’t know the difference until encountering a similar phenomenon in German, though it is more complicated in German: rather than having just one word to encompass all personal objective cases (whom in English), indirect and direct objects are distinguished. Fortunately, English’s system is remarkably simple, relying entirely on the basic understanding of subject and object—no mess with indirect and direct objects. For more help with subjects and objects, see my previous hub.

Example 1

Sandy visited her mother.

Dissect this sentence for yourself. What is the action? Who did the action? Who received the action?

- Action: Visiting

- Subject, aka doer of the action: Sandy

- Object, aka receiver of the action: her mother

How would you ask about the subject?

- Who visited her mother?

How would you ask about the object?

- Whom did Sandy visit?

It may help to be aware that the object is often preceded by a preposition, such as of, to, in, with, or at. Prepositions introduce an object and describe its relationship to the subject. Not all verbs require a preposition: in the above example, the relationship is implied in the verb, to visit. Very often, though, a preposition is used directly prior to the pronoun or at the end of the sentence.

Example 2

Adam read aloud to his son.

What is the action? Who did the action? Who received the action?

- Action: Reading

- Subject, aka doer of the action: Adam

- Object, aka receiver of the action: his son

How would you ask about the subject?

- Who read aloud to his son?

How would you ask about the object?

- To whom did Adam read?

- Whom did Adam read to?

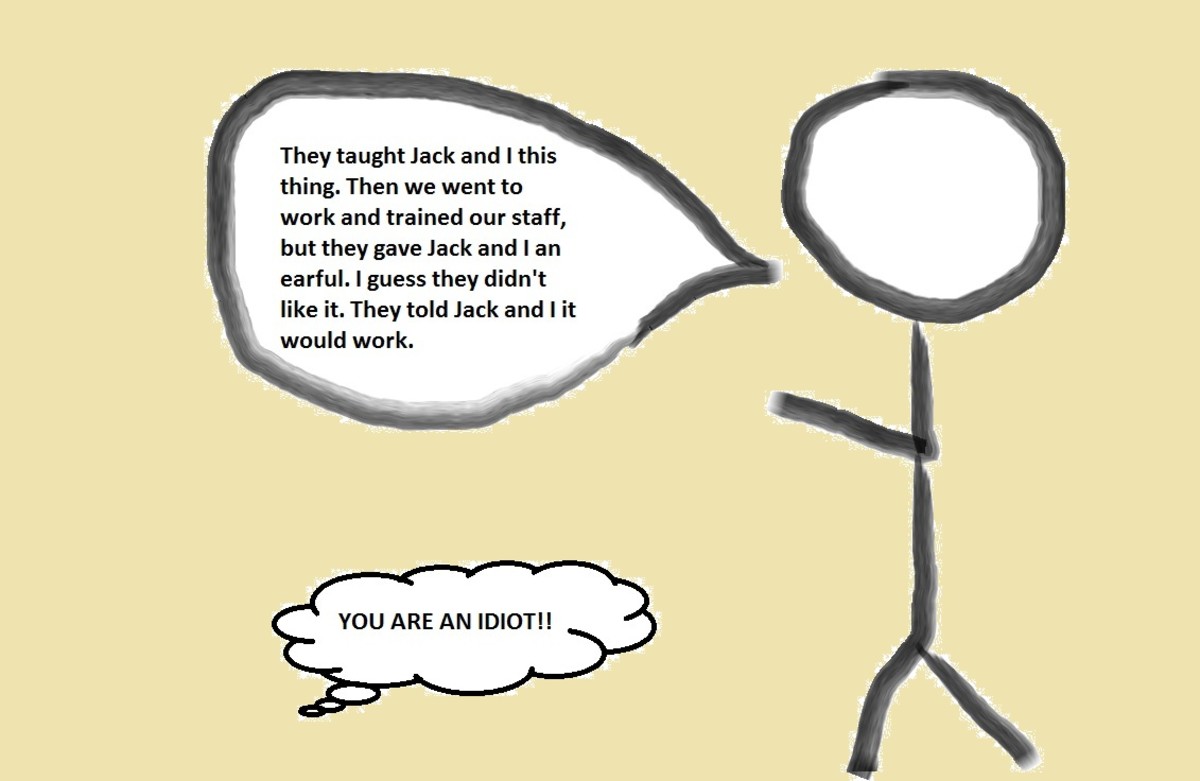

That

Things...and sometimes persons

That belongs to things; it can also be used to refer to generic persons (who suits particular persons).* “Generic persons” may include such antecedents to that as anyone, all, no one, and a man. The use of that in reference to persons is a polemic matter, often accused of having dehumanizing implications, but it is grammatically correct in many cases. Grammarians’ stipulation that that be the only defining relative pronoun contributes to this controversy. If who is strictly a non-defining relative pronoun, then either that must be used to refer to persons in defining cases, or defining cases must be avoided altogether in reference to persons.

Possessive Forms

Possessives of that: none (must borrow whose or of which)

Defining Relative Pronoun

That is the only defining relative pronoun.

A defining relative clause identifies and limits the noun.

A defining clause does not need to be preceded by a comma, and in some cases, that may be omitted completely.

Example:

He described films that he wanted to see.

- The that-clause (“that he wanted to see”) limits the noun (“films”).

That and which both refer to things. The essential distinction is that which is non-defining while that is defining. Strunk and White illustrate this well in the following extract.

The lawn mower that is broken is in the garage. (Tells which one.)

The lawn mower, which is broken, is in the garage. (Adds a fact about the lawn mower in question.)

That must be the first word of the clause, so any governing prepositions must come at the end.

- Example: The film that I told you about. The sentence cannot be written as, The film about that I told you.

Which

Things, not Persons

Which belongs to things, not persons.

Possessive Forms

Possessives of which: of which. This is a tricky matter; strict adherence to tradition dictates that whose remain a relative pronoun of people, never of inanimate objects. A Dictionary of Modern English Usage rebukes this taboo, which results in “artificial clumsiness” as writers formulate senses better served by whose to incorporate of which or even in which.

Fowler provides the following sentence, which awkwardly avoids whose:

“The civilians managed to retain their practice in Courts the jurisdiction of which was not based on the Common Law.”

- Fowler suggests that the intelligibility provided by replacing "Courts the jurisdiction of which" with "Courts whose jurisdiction" is well worth breaking the taboo.

Shakespeare, famous for his grammatical flexibility in the interest of poetic language, demonstrates the historical usage of the inanimate whose: “My thought, Whose murder yet is but fantastical” (Macbeth). Milton agrees with this flexible approach: “The fruit of that forbidden tree whose mortal taste Brought death into the world” (Paradise Lost).

Non-defining Relative Pronoun

Which, like who, is a non-defining relative pronoun.

A non-defining relative pronoun does not define the noun, for the noun does not need defining. It instead adds information.

Non-defining clauses must be preceded by commas.

Example:

I often watch Ingmar Bergman’s films, which are some of the best ever made.

- The which-clause does not limit the noun, and the sentence would be complete without the clause. It instead adds information, such as a new fact or explanation.

The preposition governing which can come before it or at the end of the clause.

- Example:

The film about which I spoke to you.

The film, which I spoke to you about.

Propriety of Which

A misperception has prevailed among some literary circles that which is more proper than that, especially in writing. As a result of misguided attempts to replace that with which, the essential nature of which as a non-defining pronoun has been ignored and awkward, grammatically incorrect sentences have been penned.

Below, taken directly from Fowler’s Dictionary of Modern English Usage, are verbatim newspaper extracts that illustrate this error, and the author’s emendations for clearer sentences.

Original sentence:

“Visualize the wonderful things the airman sees and all the feelings which he has.”

- Problem: Both clauses are defining, so which must be deleted or replaced with that.

- Emendation: Visualize the wonderful things the airman sees and all the feelings [that] he has.

Original sentence:

“The class to which I belong and which has made great sacrifices will not be sufferers under the new plan.”

- Problem: The first clause (“the class to which I belong”) is defining and should therefore use that, while the second (“which has made great sacrifices”) is non-defining, so and must be omitted and commas should be used.

- Emendation: “The class [that] I belong to, which has made great sacrifices, will not be sufferers under this new plan.”