- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Literature»

- American Literature

Are Authors Still Relevent?: A Critique of Barthes and Other Theories

In his paper, The Death of the Author, Roland Barthes argues that the author him or herself is not to be taken into account when attempting to interpret a work of literature. Barthes contention is that by doing this we expose the work to a kind of “interpretive tyranny” (1) where the work of literature is inseparable from the biography and intentions of its creator. Barthes thinks that the audience must liberate a work of literature from the ties to the author in order to truly appreciate it. The purpose of this paper will be to examine the argument for Barthes's views and then criticism that could be made by using works of literature as examples. Finally, I will compare Barthes's view to that of Arthur Danto in his work The Transfiguration of the Common Place.

If one is to look at the trend of memoirs dominating the best seller list over fictional works in recent years it is easy to see how literature itself has become so intertwined with the story behind it that interpretation has become almost meaningless. A number of popular memoirs have been proven to be false over the past several years, resulting in outrage from many who have felt betrayed by the fact that the author did not really live the story that was told. Many of these memoirs involve stories so outlandish that the fact that a person would actually believe them is itself troubling.

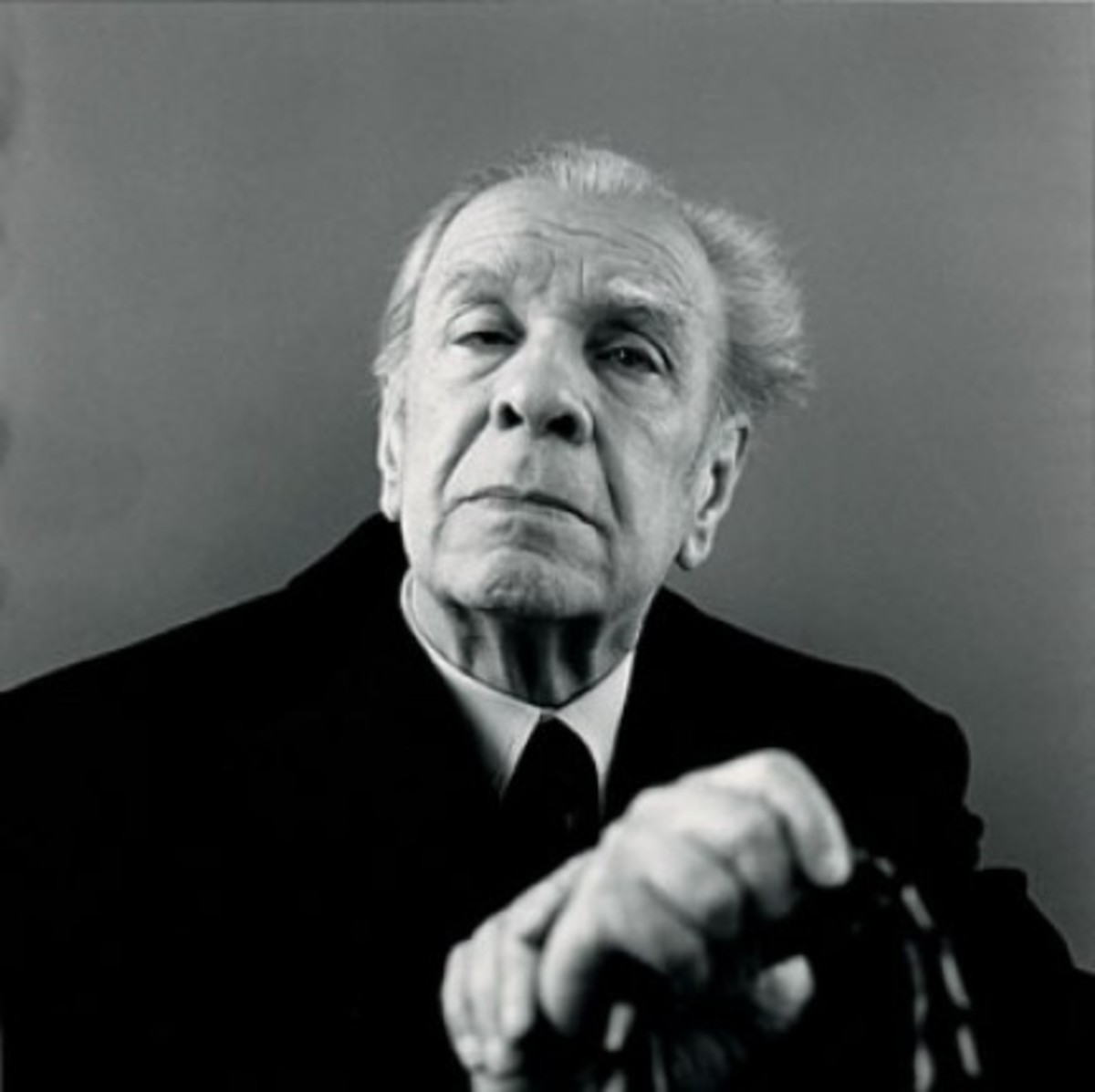

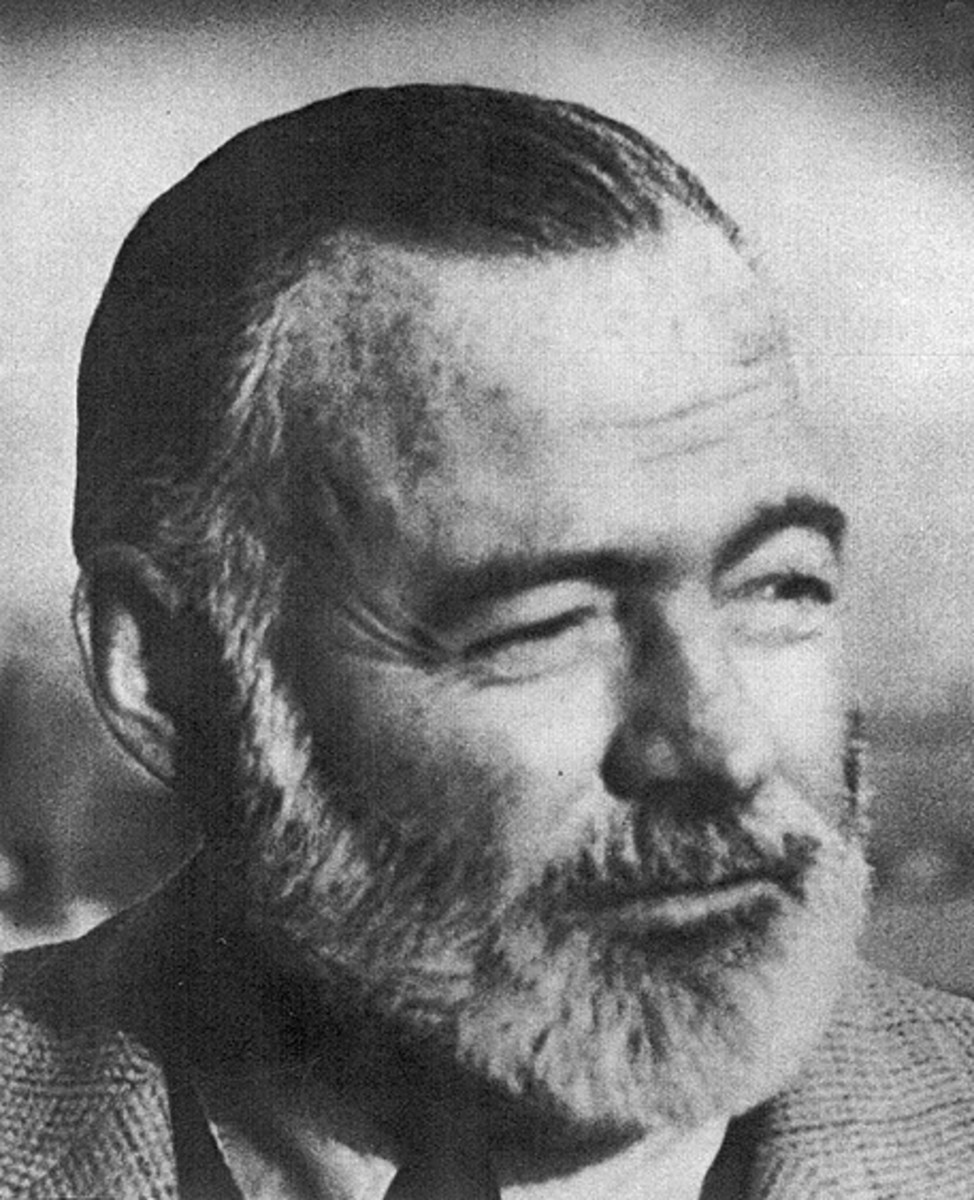

Many authors biographies have traditionally seemed more amazing than the stories in their fiction. Ernest Hemingway’s fiction is inseparable from his life, his machismo and alleged misogyny are things in which the interpretation of his work is constantly filtered through. With the majority of literary writers now living lives from academia, writer’s like Hemingway seem absent and perhaps it is the memoir that has taken its place.

There are two obvious questions that should be asked. The first is, is this a good thing for literature? The second is, are these biographies of these artists any more a reflection of reality than their art is? The first question would be easily answered by Barthes in the negative. An association of an artistic work as portraying some kind of objective knowledge has been a criticism of art going back to Plato, but in this case the idea that a memoir portrays the objective truth of a story seems counter to the role of interpretation in art, which is a key component that art plays in society.

The answer to the second question may feed into the first. There is a story about Ernest Hemingway drinking sixteen mojitos at a bar in Cuba, a record for any one person. A statue of Hemingway is erected on a bar stool there and the story itself is one of the most famous told about Hemingway and his much discussed drinking. The idea that this story is necessarily true though is questionable. Hemingway himself never wrote about it and it has been mostly repeated word of mouth. The statue itself was not made until after Hemingway’s death. Furthermore, a man who drank sixteen mojitos would normally be looked at in disdain for this unhealthy act by many but it is the fact that Hemingway is a “great writer” that makes the story itself interesting not the story that makes Hemingway a great writer.

In this case we have the story made more interesting by the literary work not the other way around. When we look at the memoirs it is the belief that the story is true that is the draw to most readers but a work of literature can never convey an objective truth, only subjective ones. When a writer sits and attempts to express a feeling of a moment he or she is limited by language at how this feeling can be portrayed. In this way language is manipulated by the writer to attempt to approximate some kind of feeling or mental process in the reader but it is not the truth of the moment that a writer feels that is conveyed or can be conveyed. It is language itself that is being experienced by the reader.

A memoir will be structured in a way so that it can convey a certain experience but that experience is not the objective truth of the event. What is being conveyed through language is the attempt by the author to interpret the truth and then convey that interpretation to the reader. For the reader to have their interpretation of the work to rest on its ability to convey objective truth is to miss the whole point of the exercise itself. The writer is incapable of conveying truth to the reader but is capable of using language to try and manipulate a kind of response.

In this way we see what Barthes is getting at when he proclaims the “death of the author.” When a person visits Havana and sees the statue of Hemingway erected and hears the often repeated story the idea of whether or not the story is true does not mean a thing to how the story is interpreted. Where Barthes runs into some trouble is that in this case the story itself results in an interpretation of Hemingway that is based on some familiarity with his work not an interpretation of his work based on who he is.

This suggests that although the idea that the author is relating something of themselves through the work can be questioned, it may not be as easy to extract the author from the work as Barthes seems to imply that it is. The process of writing itself can help make a case for Barthes's claim in that although the writer creates his or her work it is also conformed to fit a normative standard of story structure and is limited by common linguistic interpretation. If the author instead wrote in a truly stream of consciousness style it might end up being incomprehensible to many and in this case might make any kind of interpretation impossible. In this way, the author of a work is, as Barthes claims, language and society, not a single individual.

What is lacking in Barthes’s theory is a way to account for the fact that language can be so limiting that communication may be made easier by some knowledge of authorial background. In this case truth might not be necessary either. An author could lie about the background of the creation of a certain work in order to consciously manipulate a response to things that the author wants the reader to be aware of while reading. Similarly, an Author could create a fictitious pseudonym in order to manipulate the reader. In this way the authors “background” itself becomes part of the work.

This brings us to an understanding of the theory put forth by Arthur Danto when he states that a work of art is given meaning by an interpretive collaboration between artist and audience. (3) The artist inhabits a time and perspective of his or her own and any audience member one of their own. The purpose of the work of art is to bridge the gap between these two perspectives and as such the artist will always matter but the work is never truly complete until an attempt is made by a viewer to interpret meaning and this interpretive meaning is a ultimately a hybrid of the worldview of the writer and the reader.

While examining this way of looking at literature, an interesting question comes up when we examine the art of pastiche. If each author has a unique interpretative relationship with each reader what happens when that reader becomes the artist? This brings us back to Barthes’s claim of a lack of real ownership of the author over his or her work. What we consider to be any author’s “style” can be accounted for by their influences. In this way any author is simply doing a kind of synthesis of pastiche on all their influences and saying that there is any real contribution apart from what influences the author has chosen to draw from is either insignificant or absent altogether.

Now when we imagine the conscious pastiche we have several levels of interpretation. In his short story collection Werewolves of our Youth, Michael Chabon pays tribute to the work of H. P. Lovecraft with a story called The Black Mill. The story follows Lovecraft’s basic moody style and gives a story of an academic who comes to a small town where people are often mangled in the town’s old mill. Like most Lovecraft protagonists the main character believes he has a firm grasp on reality and has his ideas of what is truth and knowledge slowly stripped away as the story progresses. To add another level of play, Chabon claims the story is not his at all but a “lost story” by a fictitious pulp horror writer named August Van Zorn who had appeared in Chabon’s novel Wonder Boys as a childhood hero of that novel’s protagonist Grady Tripp.

If a reader is a fan of the Pulitzer Prize winner Chabon but also has an appreciation of the pulp fiction of Lovecraft then the story offers several levels of interpretative play. Where does the Lovecraft influence end and Chabon begin? How does this story reflect back on Chabon’s other work using Van Zorn? How does Chabon’s view of Lovecraft differ from my own? In this way we seem to have found a counter example to Barthes’s claim in that the knowledge of authorial background has three levels to add interpretation to the reader’s own interpretation. It is worth noting that many literary critics considered the Black Mill to be the best story in Chabon’s collection while many others thought that writing pulp horror was beneath his talent as a writer of literary fiction.

The question we must ask now is does this story offer anything to somebody who does not know Lovecraft’s work but knows Chabon’s? While this may be a question that answering may be an impossibility I have no doubt that there are many who would say that a conscious pastiche has no value for those who do not know the work of the author being imitated. As a reader of horror I can say that Lovecraft pastiches are incredibly common but seldom are they done as skillfully as Chabon is able to accomplish. It would be my personal view that a knowledge of Lovecraft would not be necessary in order for the story to be appreciated.

What if we give the story to the reader who is an expert on Lovecraft but knows nothing of Chabon? Despite the fact that the story is easily identifiable as a Lovecraft pastiche and is regarded by many as one of the best ever the fact that Lovecraft did not write it would be obvious to anybody who studied Lovecraft. While Chabon imitates Lovecraft’s strengths very well he intentionally disregards one of Lovecraft’s chief “flaws” by valuing character over mood. Some Lovecraft stories are so intent on mood that they have hardly any dialogue but in the stylistic differences between Chabon and Lovecraft the cracks in his imitation begin to show.

This strongly suggests that Chabon brings something different to the table. Whether it is something uniquely belonging to him or could merely be accounted for by his different influences I cannot say. What I can point out is that when authors have taken on pseudonyms in order to write in a different genre or any other reason their identities rarely remain secret. Fans of the author can identify their narrative voice even when they are making deliberate attempts to change it and this suggests strongly that while Barthes theory may point out the problems that an over reliance on authorship can bring there are elements that an individual brings to their work that cannot be accounted for.

1. Roland Barthes, The Death of the Author in Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art edited by Christopher Janaway (Blackwell Publishing, 2006) 58-77

2. Plato, The Republic in Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art edited by Christopher Janaway (Blackwell Publishing, 2006) 7-22

3. Roger Danto, The Transfiguration of the Commonplace in Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art edited by Christopher Janaway (Blackwell Publishing, 2006) 198-219