- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Literature»

- Literary Criticism & Theory

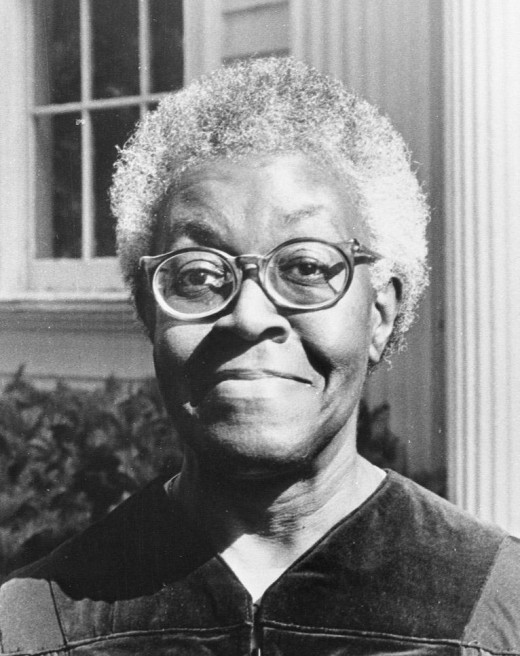

Author Discussion: Gwendolyn Brooks: An Intellectual

Intellectuality

An intellectual is defined by the Random House Dictionary in the following four ways: An intellectual is (1) “a person of superior intellect,” (2) “a person who places a high value on or pursues things of interest to the intellect… especially on an abstract and general level,” (3) “an extremely rational person; a person who relies on intellect rather than on emotions or feelings,” and (4) “a person professionally engaged in mental labor, as a writer or teacher” (Web). However, while those dictionary definitions certainly prescribe the use of the term “Intellectual,” the dictionary definition might not be the only form. Firstly, what does it mean for a person to be of superior intellect? How is intellect defined in that way? Let’s say, for the sake of argument, that we define a person of superior intellect as an individual who is able to understand a great many things about a great many things (depth of knowledge as well as breadth); if a person fits that description, but relies on emotions or feelings rather than rational intellect, does that cause that person to cease to be an intellectual? What if one only fulfills two of the four qualities that the Random House Dictionary supplies – is that person an intellectual? Or, is the intellectual something more? Is there something that the intellectuals are supposed to be doing with their superior intellect?

Is there such a thing as a political intellectual? Noam Chomsky, in his article “The Responsibility of Intellectuals” writes that “it is the responsibility of intellectuals to speak the truth and to expose lies.” This would presume that the intellectual either knows, comes to know, or is charged with coming to understand what is truth, and what are lies, and thereby speak or expose as needed. But, to be an intellectual, do you need to have an innate understanding of what is true and what is a lie? Or is it that the intellectual must simply speak truth and expose lies when they come to light, or otherwise become obvious to the individual? Mensa, an internationally-recognized organization which prides itself as an organization of intellectuals, has exactly one criterion for membership – the individual must score within the top two percent on the IQ test, at a global level. According to that logic, the IQ test would be able to flawlessly determine whether the individual is an intellectual. However, does passing an IQ test require that the individual is “professionally engaged in mental labor, as a writer or a teacher?” Statistically speaking, while it is highly unlikely, it is possible, even eventually probable, for a seven-year-old to take an IQ test and score within the top two percent on a global scale. More importantly, if an individual cannot achieve such a score on the IQ test, does that presume that that individual is not an intellectual?

Is there such a thing as an academic intellectual? Does one’s education play a role in whether an individual is to be considered an intellectual? If so, does it require a high-school diploma, or perhaps a college degree? Is it enough to have an undergraduate degree, or is one required to pursue a master’s degree, or a doctorate? If an individual strives to achieve his or her doctorate in ophthalmology, but does not “place a high value on… things of interest to the intellect,” does that still qualify him or her as an intellectual? What if someone does fit the dictionary definition above, but has no formal education at all? Can they still be considered an intellectual? Steven Colbert, of the satirical “Colbert Report”, has been awarded an honorary “Doctorate of Fine Arts” from Knox College. If Steven Colbert is an intellectual, is it the fact that he has the honorary degree that makes him so, or is it that he was an intellectual beforehand, which prompted the honorary degree? Maya Angelou, long considered an intellectual, also has no formal education, but, instead, has several advanced honorary degrees.

Is it range of influence that makes an intellectual? Is it a desire to educate that makes an intellectual? If one is of a superior intellect, but never desires to share that intellect with the world, does that qualify that individual to be intellectual? In the event that a writer of poetry dies, and, after his or her works have been published, is considered to be a great intellectual, was he or she an intellectual before he or she was discovered? If his poetry had never been published, would he still have been an intellectual? That is to say, does an intellectual have to be recognized as such by a third party to be an intellectual?

Is intellectuality age-related? Is it required that a woman or a man reach the age of fifty before she or he are to be considered intellectuals? Or, maybe thirty years are requisite? “Most of what [Albert Einstein] did, woven into the mesh of all future civilization, came about from the long, long thoughts of a youth of twenty-six. Like Newton, Einstein finished his greatest work before the age of thirty” (Harrison). What about a young girl, four years of age, who sits in her room every night drawing with crayons on a piece of paper? In her mind, she comes to understand great mysteries, which she expresses on that paper. In her mind, she is playing out great wars, romantic comedies, fairytales, and dreams; the world sees scribbles on a page. Is she an intellectual?

Gwendolyn Brooks

So, perhaps the intellectual is more than just someone with a superior intellect, or someone with a degree. Perhaps, there is no definite, singular definition of what it means to be an intellectual, but individuals can certainly be defined as intellectuals with a compilation of those qualities. Gwendolyn Brooks, in addition to fulfilling many of the definitions offered above, requires a unique set of criteria if she is to be defined as an intellectual. Her poetry serves as a direct witness to her intellect and, thus, will be used to support the unique definition of intellectual applied to Brooks hereafter. Specifically, this dissertation will treat several poems from Brooks’ Blacks to facilitate the definitions below. In the definitions above, there is a shared sense of literary works having to do with the title of intellectual; as such, Brooks will be defined in terms of her linguistic intellect. In addition, there is a sense that one’s experience has to do with whether one is to be determined an intellectual. For this reason, Brooks will be defined in terms of her experiential intellect. Moreover, there is a sense of the intellectual’s social and political obligations. The third part of the equation, then, will be Brooks’ socio-political intellect.

Linguistic Intellect

Brooks, in Blacks, provides several examples of her linguistic prowess: Her poetry is comprised of deliberate, thoughtful word choice and the modification and alteration of standard syntax which techniques, in turn, yield themselves to a distinct result which could not otherwise have been obtained. In addition, the individual with a high linguistic intellect is able to use the placement of words on a page to his or her advantage. Indeed, the very punctuation, or lack thereof, can even be modified to produce a desired result. Similarly, the usage of simple sentences and phrases in certain places, and more complex sentences and phrases in other places for the purpose of creating meaning is a sure sign of a linguistic intelligence. Brooks has proven herself to be quite skilled in these facets, thus providing evidence of her linguistic intellect.

The Pool Players: Seven at the Golden Shovel

We real cool. We

Left school. We

Lurk late. We

Strike straight. We

Sing sin. We

Thin gin. We

Jazz June. We

Die soon. (Brooks 1-8)

To illustrate these literary techniques, I have chosen one of Brooks’ most famous poems. “We Real Cool” has been described by Hortense J. Spillers as illustrating “the wealth of implication that the poet can achieve in a very spare poem” (225). The poem, reproduced to the right, certainly deserves being referred to as spare, but the depth of the poem leaves nothing to be desired:

As noted above, Brooks illustrates her linguistic prowess by signifying much with a very short poem. Brooks could have simply written “There are seven school-aged children at the pool hall who are rejoicing in the fact that they abhor education and probably don’t understand that their actions lead them to a speedy death, either physically or intellectually speaking,” and not have achieved as much meaning as she did in the form that she chose. She purposely breaks standard placement of words on a page to emphasize the “We” as outside of the sentence. In addition, the sentences are small, which serve to reflect the students’ own understanding of the English language. In an interview about this poem, Brooks commented that “[Y]ou’re supposed to stop after the “We” and think about their validity… I say it rather softly because I want to represent their basic uncertainty, which they don’t bother to question every day, of course” (Stavros). In another statement, she instructionally writes, “The boys have no accented sense of themselves, yet they are aware of a semi-defined personal importance. “Say the ‘We’ softly”, instructs Brooks (“Report from Part 1”).

Thus, we find that Brooks is capable of deliberate, thoughtful word choice, determined by having a direct connection to the desired result which serves to govern the visuospatial layout of the poem. She uses the punctuation creatively, and to her advantage, rather than allowing it to limit her to standard grammar rules. Brooks plays with the rhythm of her poetry which yields a specific result. In the case of “We Real Cool,” this result is an abrupt missing “We” at the end of line eight, which speaks directly to the children spoken of in the poem. The reader is given to ask “Do the children themselves not realize the abruptness of their death if they continue along that pathway?” In this fashion, Brooks clearly demonstrates that she possesses a distinct linguistic intelligence.

However, sharp linguistic skill is only part of her intellectual sensibility. A poet cannot simply craft his or her poetry from the aetherstuff, but, rather, must consider his or her experiences and bring together a composition which is in accordance with those experiences, in discordance with them, or some combination of accord and discord which works to paint a picture to the desired result of the poet. It is no different with Gwendolyn Brooks. To illustrate this, I will use several poems from Blacks. However, before treating the poem, it important to have a concept of how Brooks came to write poetry initially.

Experiential Intellect

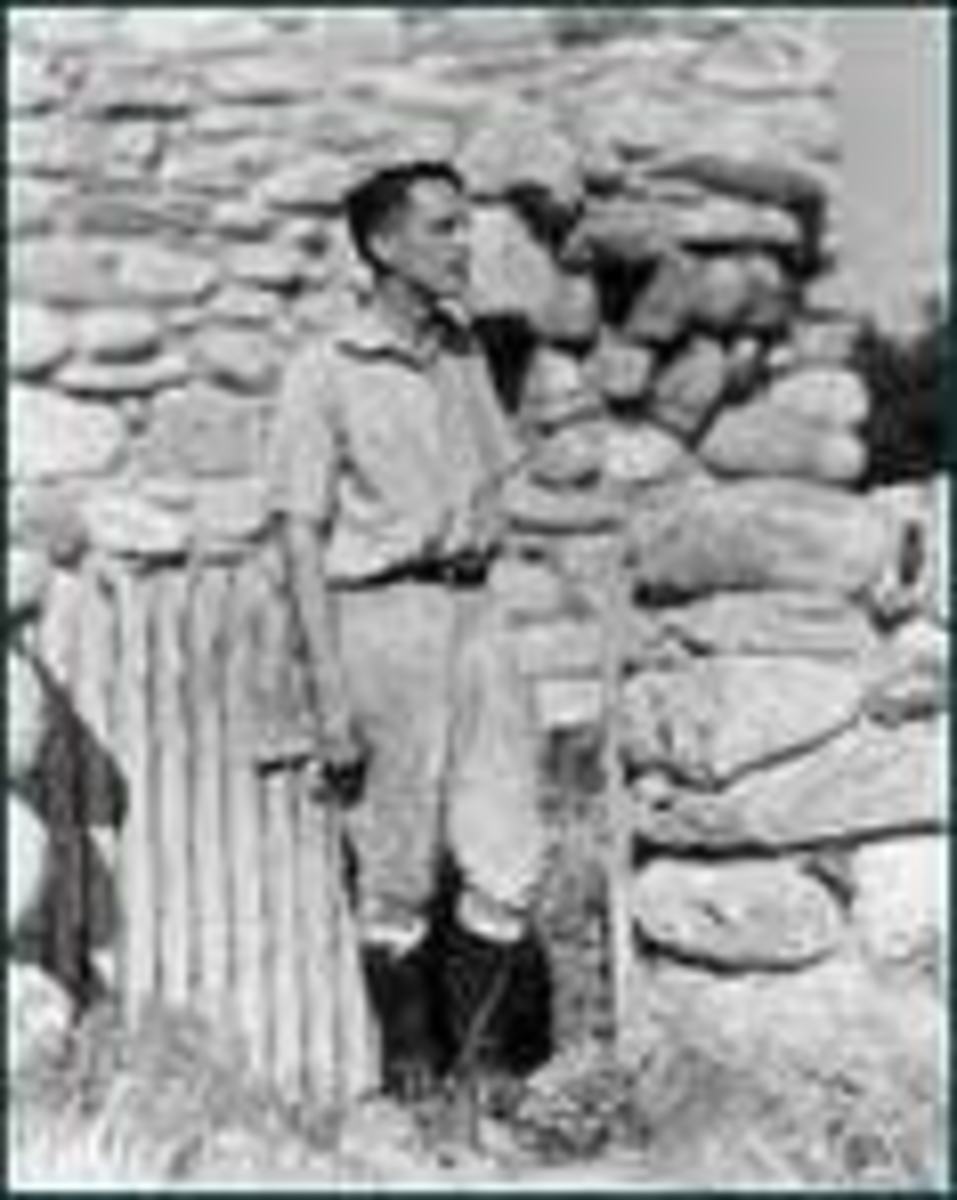

Born in Topeka on June 7th, 1917, Brooks’ talent was quickly discovered at the age of seven when she is reported to have written several “surprisingly good four-line verses” (1 Kent). It is at times like these that parents have a (sometimes frightening) amount of power. Gwendolyn’s parents, Keziah and David Brooks, however, were very supportive of this talent, and gave her the time and the support that she needed to hone her skills. George E. Kent, author of A Life of Gwendolyn Brooks, maintains that, for Brooks, her childhood was quite memorable. He writes a long list of the various meals they would have over the course of the week and that their dinners may have consisted of “hamburger patties, pork chops, or lamb chops, and a salad that almost always contained sliced tomatoes” (3). Brooks may not have been, and certainly was not, born into the wealthiest of families, but Kent describes her family as “good-doing people determined to live within a firm moral ordering.” At the age of seventeen, she began writing new-year’s resolutions. Among her resolutions were to “Write some poetry everyday [sic], Write some prose everyday [sic], Draw everyday [sic], Practice the piano continually, Use correct English, and Become pleasanter.” Four months later, Brooks would revise her list to include only one item from the previous list (Become pleasanter), and would replace the others with practical, reasonable goals such as to “Have at least ten stories accepted and paid for by January 1st, 1935” (1-34 Kent). Over the course of her youth, she attended tree high schools and a Junior College (the last of which she graduated from). These four schools gave her an experience with race relations that wove itself throughout all of her poetry. Many poems in Blacks exemplify the interwovenness of her personal experience.

The Near-Johannesburg Boy (Excerpt)

Those people

do not like Black among the colors.

They do not like our

calling our country ours.

They say our country is not ours.

Those people.

Visiting the world as I visit the world.

Those people.

Their bleach is puckered and cruel. (Brooks 4-12)

The Third Sermon on Warpland (Excerpt)

“But WHY do these people offend themselves?” say they

who say also “It’s time.

It’s time to help

These People.” (Brooks 94-7)

“The Near-Johannesburg Boy”, a much longer poem than “Seven at the Golden Shovel”, is a good example of Brooks adding her experience into her poetry. In this poem, Brooks writes the following:, reproduced to the right:

In these lines, Brooks explains what she perceives from the perspective of the boy from near-Johannesburg. “Those people”, are the racist whites, who “do not like Black among the colors.” Here she speaks to the role of whiteness in the world. Bleach, a substance standing in for “that which whitens”, is called cruel, and puckered, or roughened, because it divides. In “The Third Sermon on Warpland”, Brooks speaks to this further when she writes (reproduced to the right):

Brooks capitalizes “These People” to emphasize that the discord prevalent in society is even to be found in the language that is used by whites to describe African Americans. Thus, it is clear that Brooks calls forth her poetry from her experiences.

Intellectual Character

According to Ron Ritchhart, there are six dispositions of the intellectual character. Of these six, there are two which apply specifically to Brooks. I equate these to an experiential intellect, because they are necessarily built upon one’s past experience in order to function. Ritchhart first cites the intellectual’s disposition of open-mindedness. All of Brooks’ poetry reflects this aspect of her psyche, in terms of the words she uses and the ways in which she arranges them. This is very close to the linguistic intelligence mentioned above, but, then again, all forms of intellect must necessarily be related. The second disposition most applicable to Brooks is that of the intellectual to be strategic. This is exemplified above with Brooks’ New Year’s Resolutions. She revised her first set after four months when she found many of them to be infeasible or lacking value. Strategically, she narrowed down her list to seven valuable items (Ritchhart 27-30). The wide range of styles, topics and tones to the poetry bound in Blacks evidences clearly

Socio-Political Intellect

The final major piece of Gwendolyn Brooks, as an intellectual, is her socio-political intellect – That is, Brooks’ beliefs as to what her duty is as a poet to society and politics. Of course, to come to an understanding of not only Brooks’ sociopolitical duties, but, also, her perceptions thereof, one must turn to her works of literature; for it is there that the reader will find the essence of her goals. One does not write without intention (at the very least, the writer has the intention of writing), and Brooks is certainly no different. In her novel Maud Martha, present in Blacks, Brooks tells a coming-of-age story about an African American woman living during the great depression. In this fictional retelling of the life of racial, economic and gender-related conflict of the day, a period of time which coincided with her teenage years, Brooks, through the guise of Maud, concludes that, despite the woes of the great depression, “the sun was shining, and some of the people in the world had been left alive, and it was doubtful when the ridiculousness of man would ever completely succeed in destroying the world…. And, in the mean time, while people did live, they would be grand, would be glorious and brave, would have nimble hearts that would beat and beat. They would even get up nonsense, through wars, through divorce, through evictions, and jiltings and taxes. ¶ And, in the meantime, she was going to have another baby” (321-2). Maud’s conclusion that life goes on, is, in effect, a theme throughout much of Brooks’ poetry – a kind of concession that though there are definite and overwhelming inadequacies and inequalities which displayed themselves much more drastically then than now, although the problems remain, life continues to progress and that one must progress through these things while acknowledging the inequalities without silence. Gwendolyn did all of these things in her many writings.

Conclusion

Though we see that the general definition of an intellectual is broad and varying, Brooks’ poetry and prose, as evidenced in Blacks effects her definition by her linguistic intellect (which is exemplified by word choice, syntax, and placement on the page), her experiential intellect (which is the ability to bring her experiences into her poetry), and her socio-political intellect (which is comprised of the beliefs of her duty to society and politics). While these three aspects could never paint a complete picture of the life of Gwendolyn brooks, they serve to provide, perhaps, just a small portion of her intellectual life. Brooks has certainly proven, over the course of her life, that she is well-deserving of the title of intellectual.

Works Cited

“Intellectual | Define Intellectual at Dictionary.com.” Dictionary.com | Find the Meanings and Definitions of Words at Dictionary.com. Web. 19 Nov. 2010.

Bloom, Harold. Gwendolyn Brooks. Philadelphia: Chelsea House, 2005. Print.

Brooks, Gwendolyn. Blacks. Chicago, Ill. David, 1987. Print.

Brooks, Gwendolyn. Report from Part One. Detroit: Broadside, 1972. Print.

Bryant, M. “Gwendolyn Brooks, Ebony, and Postwar Race Relations.” American Literature 79.1 (2007): 113-41. Duke UP. Web. 19 Nov. 2010.

Callahan, John F. “Essentially an Essential African: Gwendolyn Brooks and the Awakening to Audience.” North Dakota Quarterly Fall 1987. Web. 19 Nov. 2010.

Chomsky, Noam. “A Special Supplement: The Responsibility of Intellectuals.” The New York Review of Books 23 Feb. 1967. Web. 19 Nov. 2010.

Dickie, Margaret, and Thomas J. Travisano. “Whose Canon? Gwendolyn Brooks: Founder at the Center of the ‘Margins.’” Gendered Modernisms: American Women Poets and Their Readers. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania UP, 1996. Print.

Greasley, Philip A. “Gwendolyn Brooks.” Dictionary of Midwestern Literature. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2001. 83-86. Print.

Harris, Marie, and Kathleen Aguero. “The Bones of This Body Say, Dance: Self-Empowerment in Contemporary Poetry by Women of Color.” A Gift of Tongues: Critical Challenges in Contemporary American Poetry. Athens: U of Georgia, 1987. Print.

Harrison, George R. “Albert Einstein: Appraisal of an Intellect.” The Atlantic June 1955. Web. 19 Nov. 2010.

Jack, Z. Michael. “That No Performance May Be Plain or Vain: Self as Art in Gwendolyn Brooks’ Bronzeville.” TimBookTu - Stories, Poetry and Essays with an African-American Flavor. Web. 19 Nov. 2010.

Kent, George E. A Life of Gwendolyn Brooks. Lexington, KY: U of Kentucky, 1990. Print.

Melhem, D. H. Gwendolyn Brooks: Poetry & the Heroic Voice. Lexington, Ky: U of Kentucky, 1987. Print.

Mootry, Maria, and Gary Smith. “Gwendolyn the Terrible: Propositions on Eleven Poems.” A Life Distilled: Gwendolyn Brooks, Her Poetry and Fiction. Urbana: U of Illinois, 1987. Print.

Schweik, Susan M. A Gulf so Deeply Cut: American Women Poets and the Second World War. Madison, WI: U of Wisconsin, 1991. Print.

Sims, Barbara B. “Brooks’s ‘We Real Cool.” Explicator 1976. Web. 19 Nov. 2010.

Smith, Gary. “Brooks’s ‘We Real Cool.’” Explicator Winter 1985. Web. 19 Nov. 2010.

Stavros. “An Interview with Gwendolyn Brooks.” Contemporary Literature Winter 1970. Web. 19 Nov. 2010.

Sullivan, James D. On the Walls and in the Streets: American Poetry Broadsides from the 1960s. Urbana: U of Illinois, 1997. Print.

Wright, Stephen Caldwell. On Gwendolyn Brooks: Reliant Contemplation. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan, 1996. Print.