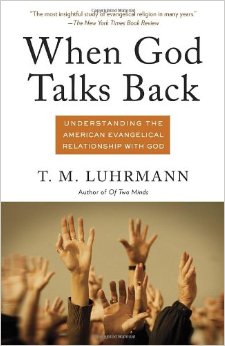

BOOK REVIEW: When God Talks Back: Understanding the American Evangelical Relationship with God

When God Talks Back: Understanding the American Evangelical Relationship with God. Tanya Luhrmann. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf Press a division of Random House, Inc., 2012. 434 pp.

Book Review

Joan of Arc was a 15th century peasant girl who experienced divine guidance though the Archangel Gabriel which helped her lead the French army to several victories during the Hundred Years’ War. She claimed to see a divine physical warrior Gabriel and to audible hear him give her comfort and direction. To our heroine, the immaterial seemed real and present. Present day encounters, such as those recalled of the Maid of Orleans, mimic what Dr. Luhrmann, an anthropologist out of Stanford University, experienced during her two years of fieldwork at a Vineyard Fellowship church in Chicago, Ill. This time forms the foundation of the research detailed in her book, “When God Talks Back: Understanding the American Evangelicals Relationship with God”.

The book begins to communicate before the first page by its impressionable cover. The book jacket represents the personal, private experience of the way people develop intense divine relationships. The almost orgasmic cover photo, coupled with the charismatic title, would surely generate conversation from your aisle mates on a plane.

For Luhrmann, among the narratives she pieced together from the Vineyard congregation, an evidence of a pattern emerged. She wondered if the ability to have these unusual spiritual experiences might be is some respects, “like becoming a skilled athlete” [P. 37]. She writes that, “what I saw was that coming to a committed belief in God was more like learning to do something than to think something” [P. xxi].

This biopsychosocial model of learned prayer runs similar to a structuralist-psychoanalyst model like the one used by Levi-Strauss concerning learned myths (Lévi-Strauss 1956:10). Levi-Strauss viewed the making real of the abstract as stemming from a human need to resolve cultural dilemmas which he found were embodied in the structure of myths (Lévi-Strauss 1956:10). Luhrmann, in her book, argues for biology’s role in creating a concept of divine communication partnering with cultural pressures. In other words, certain people are more apt to believe in the positive function of prayer because they are biologically programed too and their environment re-enforces the behavior. Using a combination of qualitative and quantitative methodology, Luhrmann led an inter-disciplinary team to examine how this belief that God personally speaks to an individual is distributed amongst the group members of the church.

To convey this, and also offer a sense of the quality of Luhrmann’s writing, here is a passage from early on in her book:

The remarkable shift in the understanding of God and of Jesus in the new paradigm churches of modern American Christianity is the shift that the counterculture made: toward a deeply human, even vulnerable God who loves us unconditionally and wants nothing more than to be our friend, our best friend, as loving and personal and responsive as a best friend in America would be; and toward a God who is so supernaturally present, it is as if he does magic and as if our friendship with him gives us magic, too. God retains his holy majesty but he has become a companion, even a buddy to play with, and the most ordinary man can go to the corner church and learn how to hear him speak. What we have seen in the last four or five decades is the democratization of God – I and thou into you and me – and the democratization of intense spiritual experience, arguably more deeply than ever before in our country’s history. [P. 35]

Luhrmann states clearly three concrete research arguments. First, she states that “talent and training are involved in the emergence of certain kinds of religious experiences” [P. 66]. Next the author purports that “people who enjoy being absorbed in internal imaginative worlds are more likely to … have unusual spiritual experiences of the divine” [P. 66]. From there the final point of the book is that there is a process called “absorption” and those “who train to develop it are more likely to have powerful sensory experiences of the presence of God” [P. 67].

Yet the author expresses as her explicit overall purpose the emphasizing of the role of skilled learning in the God experience. Luhrmann refers to it as an “ethnographic puzzle” [P. 68]. To help solve that riddle, Luhrmann wisely put together a team that included Dr. Howard Nussbaum, a psychologist tasked with helping shape the primary questionnaire, and Dr. Ronald Thisted, a statistician who did the statistical analysis of the results.

The researchers seek to examine their portion of the puzzle within the greater scope of the anthropology of religion. They acknowledge the body of literature emerging out of the sub-field that sets learning “at the heart of the process of having faith” [P. 127]. Luhrmann places her work squarely in line with anthropologist such as Saba Mahmood, Rebecca Lester, Charles Hirschkind and Anna Gade. What is lacking though is recognition of the other cutting-edge contributions made in disciplines such as biblical scholarship, philosophy of religion, American religious history or systematic theology. The intellectual achievements of evangelistic thinkers such as Alvin Plantinga, Mark Noll, George Marsden and Thomas Oden find little or mention in Luhrmann’s book. Luhrmann finds herself a niche within, and built from, her anthropological scholarly peers while ignoring evangelical academia.

In terms of theory, Luhrmann draws primarily upon two developed on existing scholarship within the anthropology of religion [P. 176]. The first theory “emphasizes the importance of the acquisition of cognitive and linguistic representation of God” [P. 176}. Here one might again recognize the need to acquire the proper language structure as a nod to Lévi-Strauss’ work on the grammatical similarities of myths. From this it is argued that language is at the center of Christianity and can be sufficient in its own standing to explain belief in God (Harding 2000:60). The religious actor must acquire cognitive and linguistic knowledge to interpret the presence of God [P. 177].

The second theory “emphasizes embodiment and sensory practice, the impact of action and phenomenological experiences on the actor” [P. 181]. Embodiment, the way people experience abstract concepts physical, and practice, the impact of what we say and do, contribute to the way divinity is identified and experienced. Luhrmann relies upon this body of work to state that “religious actors must learn to experience embodiment through particular cultural practices” [P. 183].

To this end, a combination of research methods was utilized. The ethnographic tool of participant observation showed that people who reported that they heard God often were also more likely to talk about vivid mental imagery and unusual sensory experiences, which were sometimes attributed to the phenomena of prayer [P. 201]. Quantitative methods were also introduced to measure the psychological phenomenon of absorption [P. 195}. The ethnography attempted to show a progression that had to do with the attainment of a certain skillset, and psychological tools were used to attempt to pin down the activator.

Luhrmann spent two years conducting traditional ethnographic field work, particularly participant observation, among a Chicago-based Vineyard Christian Fellowship by attending Sunday morning services, a weekly home Bible study, conferences, retreats and engaging in general casual conversations [P. 57]. Vineyard members typically tend to be biblical literalist and have a more relaxed, contemporary worship style. God is a purveyor of unconditional love and the book has no mention of hell or a punishing God. God is expected to be experienced “directly, immediately, and concretely” [P.63]. Congregants were expected to experience mental events, which were not identified as their own but instead belonging to an external presence [P. 63]. Speaking of her research focus, Luhrmann says, “In a way more fundamental than we dare to appreciate, we each must make our own judgments about what is truly real, and there are no guarantees, for what is, is always cloaked in mystery.” [P. 325]

Luhrmann conducted detailed questionnaires, designed by Nusbaum, with 28 congregants [P. 212]. The sampling was not random as the aim was to compare phenomena within the group [P. 212]. The answers were clustered into the categories of “focus”, “sensory”, and “vividness” and scored for later comparison [P. 215]. That comparison was made by also administering the Tellegen Absorption Scale to the same interviewees (Luhrmann, et. al 2010:73). This scale “taps the subjects’ willingness to be caught up in their imaginative experience and in nature and in music” (Tellegen and Atkinson 1974:268). The choices in methodology work well together to meet the needs of the research questions.

After statistical analysis, the scale, lined up to the scoring of the questionnaire, showed that those with a high score “were much more likely to report experiencing God as if God really is a person” directly lining up with the second research question (Luhrmann, et. al 2010:73). Participants that answered positively to more than half the questions on the scale were six times more likely to report hearing from God and those that did not feel like they were sensing God as the Vineyard thought they should did not think the Tellegen scale described them (Luhrmann, et. al 2010:73).

This level of data is lacking from her book, but can be found in other published sources and may give insight into the author’s intended audience. What Luhrmann does tell us is that this is, “the way people come to recognize an invisible God that the prayer books tell them is even more undefined and unexpected than they thought. They map this abstract God from their own particular lives. They use their own experience of how conversation happens and how they relate to trusted friends to pick out the thoughts and images in their minds that are like those ordinary moments, but different in certain ways” [P. 46].

The author concluded that when people believe that God will speak to them through their senses, when they have a proclivity for absorption, and when they are trained in absorption by the practice of prayer, these people will report internal sensory experiences with sharper mental-imagery and more sensory overrides [P. 346]. While part of the author’s conclusion, the book did not satisfy the burden of proof of a direct connection between the research findings and the issue of developing a skillset of prayer.

Though the data may support the research questions to varying degrees, Luhrmann fails to prove that the results from the questionnaire and Tellegen Absorption Scale do not simply overlap with the Vineyard model of the experience of God. The Vineyard church teaches the engagement in Ignatian kataphatic prayer (Miller 1997:134). This type of prayer asks one to be present in the imaginative prayer scene. It asks one to focus inwardly on internal sensory experiences. If the questions on the scale are seen to be religious in nature by the participant, than it offers no device for comparisons (Keane 2007:43). It only serves as an instrument that reflects what is already understood.

In this same vain, Luhrmann does address that her research attempts to give explanation for an “American Evangelical Relationship with God’ according to the book title, but does not account for the varying differences amongst American Evangelical experiences of God. Instead of offering a type of relationship, Luhrmann suggests a representational experience which her research sample cannot support. She admits that most members of the church were white, middle-class, college-educated and centrist (P. 58). These also present issues when attempting to paint a broad stroke on a diverse evangelical group.

What this book, and study, lacked was significant data on amount of time spent in prayer. While attempting to make the argument that prayer is the vehicle akin to exercise that makes one able to lift the heavy weights of spiritual experiences, little is done to quantify how much time one spends in the “gym”. This is an area where the ethnographic methodology was not properly aligned to the quantitated component to address the research question.

While not providing results that may impact policy and practice, one must acknowledge that religion and spirituality are enormously complex human phenomena. What might be understood is how some become gifted practitioners of their faith and others, with good intentions and desires, struggle with their faith. The book provides an important value to the scholarly literature found within the anthropology of religion. We are reminded that, “at the heart of the religious impulse lies the capacity to imagine a world beyond the one we have before us” (Bloch 2008:2057).

Quote

About the Author

T.M. Luhrmann, Ph.D. is a psychological anthropologist and a professor in the Department of Anthropology at Stanford University. She received her education from Harvard and Cambridge Universities, and was elected as a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2003. In 2007 she was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship.

References

Bloch, Maurice

2008 Why Religion Is Nothing Special but is Central. Philosophical

Transactions of the Royal Society 365:2055–2061.

Harding, Susan Friend

2000 The Book of Jerry Falwell: Fundamentalist Language and

Politics. Princeton: Princeton University.

Keane,Webb

2007 Christian Moderns: Freedom and Fetish in the Mission Encounter.

Berkeley: University of California.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude

1956 Witch Doctors and Psychoanalysis. The UNESCO Courier 9(3):8-10.

Luhrmann, T.M.

2012 When God Talks Back: Understanding the American Evangelicals Relationship with

God. New York: Alfred A. Knopf Press a division of Random House, Inc.

Luhrmann, T.M., Howard Nusbaum and Ronald Thisted

2010 The Absorption Hypothesis: Learning to hear God in Evangelical Christianity.

American Anthropologist 112(1):66-78.

Miller, Donald E.

1997 Reinventing American Protestantism: Christianity in the

New Millennium. Berkeley: University of California.

Tellegen, A., and G. Atkinson

1974 Openness to Absorption and Self-Altering Experiences (“Absorption”), a Trait

Related to Hypnotic Susceptibility. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 83(3):268-277.

Reader Poll

Did you enjoy reading "When God Talks Back"?

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2015 Brian S Brijbag Esq