- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Literature»

- Western Literature

Book Review: Walden - Henry David Thoreau

Purchase Walden on Amazon

On the surface, Henry David Thoreau's Walden; Or, Life in the Woods appears to be nothing more than the musings of a solitary, philosophically inclined Christian man who has a remarkable appreciation for nature. The semi-autobiography masquerades as the tale of a man embracing the simple life and returning to nature in the pastoral tradition of Virgil's Eclogues and Voltaire's Candide. A closer examination, however, reveals Walden to be a Transcendentalist manifesto featuring themes that are profoundly antithetical to Christian belief. In the mid-18th Century, Transcendentalist belief became tremendously prevalent in the United States, particularly in portions of New England. In the wake of the renaissance, as liberal theology and deistic belief crept into the foundations of Northeastern churches, people began to look for a way to measure their existence in terms of human experience. Transcendentalism represented a sort of Secular Great Awakening, as people began to pursue intense spiritual experiences free from the 'troubling' encumbrances of strict biblical doctrine, corporate liturgy and religious convention. Transcendentalists believed that divinity was imminently present in the natural world, and that god – intermingled with nature, thusly – could be experienced through a sort of communion with creation.

The first chapter of Thoreau's book is entitled “Economy,” and it contains the most intriguing and least harmful of the author's Transcendental musings. A stout rejection of materialism is a cornerstone of Transcendental ideology, and Thoreau dedicates nearly a quarter of his book to criticizing modern society's penchant for embracing this flawed worldview . “Most men...” he expounds, “are so occupied with the facetious cares and superfluously course labors of life that its finer fruits cannot be plucked by them...[they have] no time to be any thing but a machine,” (pp. 3). According to Thoreau, Mankind has become so fixated on accumulating material possessions that it has neglected to attend to that which is truly important, resulting in lives of “quiet desperation” (pp. 4) limited by “golden or silver fetters,” (pp. 10). The materialist's highest goal is to accumulate enough wealth to “keep comfortably warm – and die in New England at last” (pp. 8). Ultimately the materialist lives without hope, which is to say he does not live at all.

Walden's negative view of materialistic society is entirely consistent with his professed Christian faith and the inspired words of Holy Scripture. Thoreau himself makes this connection clear, declaring that materialists are “employed, as it says in an old book, laying up treasures which moth and rust will corrupt and thieves break through and steal,” (pp. 3) – an obvious allusion to Matthew 6:19. For the Christian, meaning is not found in worldly wealth but rather in eternal salvation. While – to be sure – material goods are not evil (Gnosticism is a heresy), they are not the ultimate end and can pose a significant threat to saving faith in God. After all, as Jesus reminded us in Matthew 19:24, “it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to enter the kingdom of God.” Both Christians and Transcendentalists can agree that materialism is a siren call to doom that should be avoided, and it is Thoreau's musings on the dangers of wealth that most clearly align with the reality of the human condition.

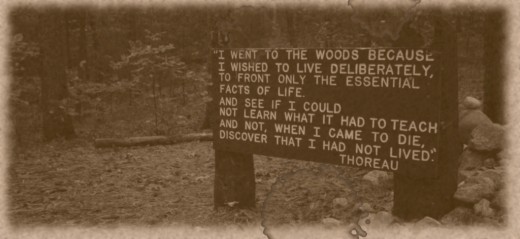

The tensions between Thoreau's professed faith and expressed philosophies begin to arise when Thoreau presents his solution to the problem of materialism. Thoreau recognizes that “moth and rust will corrupt,” (Matthew 6:19) but he does not respond by “lay[ing] up for yourselves treasures in heaven” (Matthew 6:20) by depending upon Christ for justification and pursing sanctification in his daily life. Instead, he choses to retreat to Walden Pond and find meaning through communion with nature. As he explains, “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it [nature] had to teach," (pp. 59). Though he refrained from vesting his hope material goods, he still vested them fully in the material world: “...trying to hear what was in the wind...I well-nigh sunk all my capital in it," (pp. 11). In the eyes of Thoreau, all religious doctrine was to be abandoned in the pursuit of this spiritual experience with the natural world, which he dubbed 'reality.' As he put it, let us “work and wedge our feet downward through the mud and slush of opinion...through church and state...and religion, till we come to a hard bottom in a place we call reality...” (pp. 63-64). For Thoreau, and transcendentalists, the way to achieve a meaningful spiritual existence is by partaking of the deity that is present in nature – to “root oneself firmly in the earth” in order to “rise in the same proportion into the heavens above.” (pp. 9).

As the novel progresses, it becomes clear that Henry David Thoreau has departed from orthodox Christian thought, and forsaken the gospel. He begins to describe communion with nature in religious – even salvific – terms. He writes that “every morning was a cheerful invitation to make my life of equal simplicity...with Nature herself...I got up early and bathed in the pond; that was a religious exercise...'Renew thyself completely each day,'" (pp. 58).The imagery is striking: Thoreau has been baptized in Walden Pond, not into the body of Christ, but into the bosom of the wilderness. Walden Pond thaws in the Spring, undergoing a sort of resurrection, which – supposedly – brings purification to Thoreau and mankind: “You might have known your neighbor yesterday for a thief, a drunkard, or a sensualist...but the sun shines bright and warm this first spring morning, recreating the world...and all his faults are forgotten," (pp. 203). Thoreau has forsaken the salvation of the Son of God in favor of the salvation of the sun – indeed, he has “exchanged the truth about God for a lie and worshiped and served the creature rather than the Creator,” (Romans 1:25).

Henry David Thoreau's Walden; Or, Life in the Woods is a fascinating piece of literary construction. Thoreau addresses the most prevalent problem of the modern era: how to find meaning in a society where mere subsistence in no longer a luxury. He convincingly debunks the secular myth of material salvation and rightly wonders at the beauty and order found in the natural world. Ultimately, however, he exchanges Christian faith in the salvific work of Jesus Christ on the cross for the “tonic of wildness” (pp. 205) and the false hope found in communion with nature. Thoreau writes of fishing with an older gentleman who “occasionally hummed a psalm, which harmonized well enough with my philosophy. Our intercourse was thus altogether one of unbroken harmony, far more pleasing to remember than if it had been carried on by speech,” (pp. 113). Ultimately, he is left with a but an empty shell of his Christian faith – a beautiful melody without words of doctrine in a stunning universe that provides no real hope.

Citations are taken from the Dover Thrift Edition of Walden; Or, Life in the Woods (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1995). Available on Amazon.