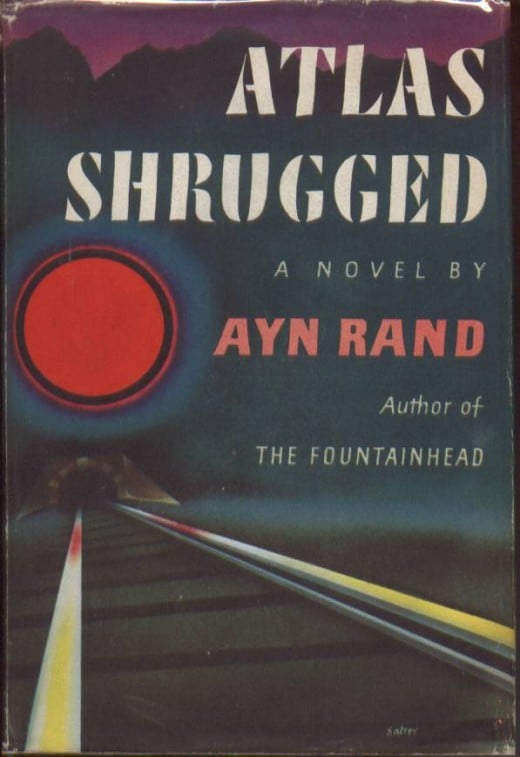

Book Review of Atlas Shrugged

Atlas Shrugged is generally considered a classic piece of literature, and an unusual and thought-provoking novel of philosophic and economic theory. I also have heard that the novel openly manifests the vitality and success of Capitalism, and yet is also lauded as a great piece of storytelling. ‘Long live the novel that does more than entertain!’ I remember thinking, and classed Ayn Rand in my mind with the Orwells and the Chestertons and the Lewises of lyric and lore, philosophy and priesthood.

My conjectures were correct in some ways, but in other ways I was quickly disappointed before I even came close to finishing the book. Atlas Shrugged, though read with captivated interest, was tossed into the closet.

Sharp and Vivid Writing Style

Ayn Rand’s style of composition was a delight from the first. Plunging forward with intense mechanical creativity, each sentence mirrors the engines it describes. With a few “sharp strokes” in black and white, abrupt but not the less beautiful for its discipline, she makes things seem direct, purposeful, and crisp.

“With the first whistling rush of air, as the Comet plunged into the tunnels of the Taggart Terminal under the city of New York, Dagny Taggart sat up straight. She always felt it when the train went underground--this sense of eagerness, of hope and of secret excitement. It was as if normal existence were a photograph of shapeless things in badly printed colors, but this was a sketch done in a few sharp strokes that made things seem clean, important--and worth doing.” (pp. 24-25, Chapter 1)

Through her string of concise garrulity, an haunting question echoes itself in Dagny’s dialogue with other characters, like the repeated line of a poem, when a situation or scenario comes up again and again:

“Who is John Galt?”

Use the Brain

I appreciated, also, Ayn Rand’s continual reminder that art, music, and literature is to think about, as well as to enjoy with the emotions. This description of a concerto was particularly revealing on this account:

“She sat listening to the music. It was a symphony of triumph. The notes flowed up, they spoked of rising and they were the rising itself, they were the essence and the form of upward motion, they seemed to embody every human act and thought that had ascent as its motive. It was a sunburst of sound, breaking out of hiding and spreading open. It had the freedom of release and the tension of purpose. It swept space clean, and left nothing but the joy of an unobstructed effort. Only a faint echo within the sounds spoke of that from which the music had escaped, but spoke in laughing astonishment at the discovery that there was no ugliness or pain, and there never had had to be. It was the song of an immense deliverance.” (p. 20, Ch. 1)

Humanism

Though I agree with Ayn Rand’s basic premise that thinking is good, reasoning is good, and using the old tiddlywinks in the attic is not usually a bad idea, I find her exultation in human reason and human accomplishment unreasonable. This song of “immense deliverance” is not Handel’s Messiah. Rather it is a soaring, marching, triumphant song of mankind’s achievement. Somehow mankind has shed its fleshly burden of “no one can do good; no, not one,” “the heart is deceitful and desperately wicked, who can know it?” and frees itself from this “tension of purpose” all on it’s own, with no divine aid. Could that tension of purpose be “the plans I have for you, declares the Lord, plans to prosper you and not to harm you, to give you a future and a hope?” I hope not.

‘Did Halley ever write a fifth concerto?’ questions the heroine. If he did, it would not be the first humanist manifesto, and it would not get far before its tongues were tangled as they were at the tower of Babel, the first soaring monument of human effort to come crashing down as the result of attempted autonomy.

Capitalism

Ayn Rand is not the first, or the last, novelist to successfully portray the functional beauty of Capitalism with a capital C. Taggart Continental Railroad is the workshop for both Dagny and Jim Taggart, two siblings with entirely different goals for their family’s business. Jim (James) is a man with no chest, though he declares his every motive is sympathy. He makes decisions that harm the railroad, --and with it, the railroad’s customers-- while trying to help the underdog, whether it be a farming town that doesn’t need a railroad, a Mexican mining town that doesn’t know how to use it, or a fellow competing railroad company. He has neither a mind for business or a heart for true charity.

“It isn’t fair,” said James Taggart.

“What isn’t?” [Dagny said.]

“That we always give all our business to Rearden. It seems to me we should give somebody else a chance, too. Rearden doesn’t need us; he’s plenty big enough. We ought to help the smaller fellows to develop. Otherwise, we’re just encouraging a monopoly.”

“Don’t talk tripe, Jim.”

“Why do we always have to get things from Rearden?”

“Because we always get them.”

“I don’t like Henry Rearden.”

“I do. But what does that matter, one way or the other? We need rails and he’s the only one who can give them to us.”

“The human element is very important. You have no sense of the human element at all.”

“We’re talking about saving a railroad, Jim.”(p. 26, Ch. 1)

Dagny’s mind works as sharply as polished steel. She sees that the success of her company will benefit others. And she is not distracted like her brother Jim, who eventually harms their company through his double-mindedness and indecision. Her motives could be labeled selfish, perhaps, but in helping her company she ultimately helps others through providing competitive service, and she sees that.

At one point, James acts out of extreme “goodwill” to the other railroads by introducing a measure called the “Anti-dog-eat-dog Rule” to the National Alliance of Railroads. The Rule would prohibit any railroad that was not in a particular territory “first,” from continuing to operate in that territory, thus promoting fairness and goodwill amongst the fellow railroads of the Alliance. Though only five people voted against the measure, everyone hoped that someone would defeat it. When Dagny heard of it, she was furious. She, and every other railroad owner, saw the reckless danger of the act. Unreliable and inept minor railroads that had happened to be in a territory “first” would take precedence over more competent and larger rails that had come to the area later. Without healthy competition, industry would have no motivation to create better, safer, more streamlined products, because they were always guaranteed a clientele, no matter if they performed poorly or magnificently. The reason for this dastardly Rule? “...the prime purpose of a railroad was public service, not profit...” (p. 76, ch. 4) according to James.

Who is John Galt? The question echoes with random desperation in yet another scenario.

The Hero or the Villain?

The nature of the book seems to groan for a savior at this point. Dagny, though driven, intelligent, and capable, is not powerful or omniscient enough to save the economy, much less her family’s railroad. Onto the stage steps Francisco d’Anconia, a wealthy oil company owner, a childhood friend of Dagny’s, tall, dark, handsome, speaking objective platitudes like prophecy, and all he predicts seems to come true. He has been blessed with an inherent understanding of how things work from a young age, and as a child, he explained complex mechanics and physics equations to his elders, scribbling formulas in the dirt with his finger. I half expected him to put the mud in somebody’s eye. When playing with Dagny and James as they grew up together, he taught them a system of virtue and motivation that continued to govern Dagny through her life and work, though James was skeptical.

“When I die, I hope to go to heaven...and I want to be able to afford the price of admission.” [Francisco said.]

“Virtue is the price of admission,” James said haughtily.

“That’s what I mean, James. So I want to be prepared to claim the greatest virtue of all-- that I was a man who made money.”

“Any grafter can make money.”

“James, you ought to discover some day that words have an exact meaning.” (p. 94, ch 5)

Dagny digs a bit deeper into this ultimate humanist’s system of virtue:

“Francisco, what is the most depraved type of human being?” [she asked.]

“The man without purpose,” [he answered.] “...There’s nothing of any importance in life-- except how well you do your work. Nothing. Only that. Whatever else you are, should come from that. It’s the only measure of human value. All the codes of ethics they’ll try to ram down your throat are just so much paper money put out by swindlers to fleece people of their virtues. The code of competence is the only system of morality that’s on a gold standard. When you grow up, you’ll know what I mean.” (p. 98, ch. 5)

I’m not sure where Francisco got this version of virtue. His view of true worth lowers the human to the value of his performance at a task, and abandons all other moral laws in the process. The laws of nature and nature’s God are nowhere to be seen; in the place of the law of God is the law of man. Man is God (or rather, has the ability to elevate himself to a “god” position); the greatest Man is the greatest God. This is what he calls the “code of competence.” If this philosophy were to be carried out into actions as a consistent philosophy should do, we would end up seeing either a complete tyranny of one Superman’s code of competency enforced on all inferiors, or else a complete anarchy, with every man committing every unlawful act he desires in order to do “his work” well and competently, whether that be murder, theft, or adultery. Francisco doesn’t take into account that there are competent thieves who do their work very, very well, yet have nothing he would call virtue.

The point at which I threw the book into the closet was the point at which Francisco and Dagny begin to exercise their competency at premarital intimacy-- given the author’s full consent, and raising them to a level of innocent deity through her description of their unabashed pleasure of the unlawful.

Francisco commented, “Isn’t it wonderful that our bodies can give us so much pleasure?” and Ayn Rand followed it up by with her own commentary: “They were both incapable of the conception that joy is sin.” (p. 106, ch. 5)

The Law of God is Good and Wise

Perhaps Ayn Rand is taking a stab at the Puritans, who are often thought to have been frowners on all forms of pleasure, rigged up tightly in black and white from birth to death. If so, she has no understanding of what the Puritans really believed. A truly Puritanical mindset is one of rejoicing in the wife of one’s youth, rejoicing in the food and the wine, rejoicing in the sacraments and the reading of the Word, rejoicing in the pleasure of intellectual stimulus, rejoicing in the law of God, rejoicing in work and labor and children and increase. Sensual love and intimacy is not “...an ugly weakness of man’s lower nature, to be condoned regretfully,” as Rand declares that moral people believe, but is rather a gift from God to a man and his wife on their wedding day.

We find in this book what one economic theorist titled “Libertarianism.” Complete freedom of conscience in business, in relationships, in politics: meaning, the fittest of the free survive, the most slovenly (or restricted by conscience) of the free will eventually fall by the wayside. Libertarianism has an unquestioning faith in the individual man (humanism); this faith has only one law, and that is that the man should not act against himself or against his own success. As long as everyone looks out for themselves first of all, then everything else will fall into place.

This is dramatically opposed to the law of God, which states that the first shall be last and the last, first. “He who saves his life shall lose it, and he who loses his life for My sake (Jesus’ sake) shall find it.” “Seek ye first the kingdom of God and His righteousness, and all these things shall be added unto you.” Ayn Rand did not understand that the human heart is in bondage to sin, to laziness, to failure. The type of liberty that she proclaims as “innocence” is impossible outside of divine intervention. The only true liberty of conscience, the only ability to do a job well, is found in Christ. Christ is the one who gives man the only competency he’ll ever have. Christ is the one who gives man a code of value that prizes the real image of God in every man --not just in the competent ones. Christ is the one who gives man purpose, joy, and something to work towards. Christ is the one that makes everything “clean, important--and worth doing.” The law of Christ is the perfect balance between the justice of capitalism and the mercy of charity. In Christ, both Dagny and Jim would run their company successfully and graciously.

Is Atlas Shrugged ever coming out of the closet again?

Label me naive or ignorant, but I am not willing to pollute my mind with lawless humanism of the graphic sort-- not even to find out who John Galt is.

Work Cited

Atlas Shrugged, Ayn Rand, (New York: Signet, a div. of Penguin Putnam, 1992)

© 2010 Jane Grey