Bridges and Connections

Sometimes we can stand back and view the past from an adult or dispassionate perspective, yet at other times, our memories are so embedded in the feelings, in the language, in the atmosphere of those times that it would be inappropriate, or too difficult, to try to disassociate one’s self from those events and their memories. So the retelling becomes a journey into the past, through the past, of the past.

Join me here, as I draw my life out of dark and happy places, but forgive me if I linger there when you have tasted and experienced, those events with that other me, and you have then moved on.

Cunard White Star SS Scythia

It was 1948, and my parents and I had arrived in Australia from India. We had arrived at the docks at Fremantle on the Cunard White star SS Scythia’.

We had been thrown out of India. Partition. How could I have been thrown out? I was an Indian. I had been born an Indian… and although I didn’t know it then, I would always remain an Indian… or as I was to discovered later, a Pakistani.

Quetta. It is the capital city of Baluchistan. The ethnic inhabitants of Baluchistan are called the Baluch… My father often said, “Always remember you are a Baluch, my boy”.

I was a Baluch. I was an Indian.

Partition had separated the Hindu from the Musalman; the Musalman from the Sikh… but how could it separate me from my own country?

“Always remember you are a Baluch, my boy”.

I don’t know how many times my father would say to me that my country was India. Sometimes, apropos of nothing, he would turn to me and say,

“Always remember you are a Baluch, my boy”.My father told me quite frequently that I was a Baluchi.

A strange anomaly in that, on one hand he would constantly be trying to confirm in me that I was an Indian, but he had been most worried when I had spoken in Urdu or Hindi or Marathi, with the servants and the other Indians with whom I came in contact on the Cantonment.

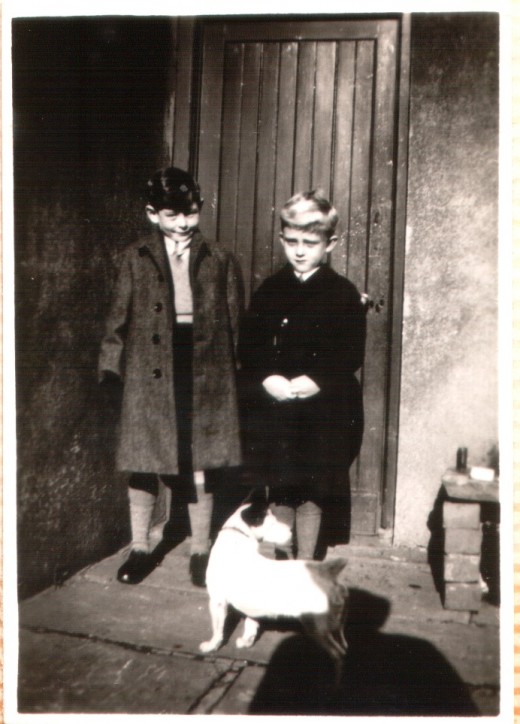

I was born in Quetta, the Capital City of Baluchistan. My father was in the British India Army and his wife, my mother, was the Memsahib.

When I was very small, my parents employed an Ayah, a Baluchi lady who took care of me, as a nanny does in Britain. I have vague memories of her. They are of a lady wearing a very dark red sari, perhaps, and my memories also bring to mind a lady who treated me with love and affection. And I also remember that she had bare feet which were as hard as leather, but very gentle hands, as soft and kind as any mother's to her child. I adored her.

She was responsible for my feeding, my well being, my care and everything that a mother lavishes on a loved child. I have a feeling that she also was my wet nurse, as my mother had been quite ill before and after my birth, and was not particularly robust. My memories of this lady, my Ayah, are vague, but also they are lovely memories, because I really became very attached to her.

This was all very well, but it caused some concern, as my parents realised quite soon that I was beginning to talk to her in Barohi and Baluch, as these were the languages with which she was familiar. Baluch is the language of the ethnic Baluchi, and Barohi (or Brohi) is the Classical Language of Baluchistan.

The nursery rhymes she used to soothe me to sleep and which I learned were in Urdu and Barohi. One which I loved went something like:

Nini baba nini (Sleep baby sleep,)

Muckan roti chini (Butter, bread and sugar,)

Nini baba so giah (Sleepy baby satisfied)

Muckan roti hogiah (Bread butter finished)

My God! The Little Chap's "gone native".

My parents became even more concerned, as I was happy to speak not only Barohi, and Baluch, but also Urdu; all to the exclusion of the English language. There was quite a “fear” within British India society that people would “go native”; that they would become too well assimilated within the native culture and population. The British officers, especially, were encouraged to speak at least one of the “Native” languages, so as to be able to communicate with lower Indian Ranks and with servants, but all else was frowned on.

There had been a Viceroy who had “Gone Native”. Horrors!

This little Chota Sahib was in danger of going native and seemed happy to do so. So my Ayah was taken away from me, and I was encouraged to speak English as much as possible. My mother, being Welsh, also taught me to speak her mother tongue.

But I took to speaking the native languages like a duck to water, and by the time I was nine years of age I could speak Brohi, Baluch, Welsh, Urdu and Hindi (basically the same really) because I lived in India and most of us spoke the language, anyway and also Marathi because Krishna, our bearer, was Marathi speaking and we lived in Dehu Road Cantonment which is near Poona (now Pune) in Maharashtra Province.

So going to Australia was easy, and I picked up that language quite quickly! After all, the Australians have spoken a form of English for years and years.

The North Perth Hotel

We had arrived in West Australia in February of that year. It was hot, and as far as I could see, it was not unlike the country from which we had come. It wasn’t as hot as it was at home in India, in the Dehu Road Cantonment, but it was still very hot, and dry.

For the first few weeks we lived at the North Perth Hotel.

It was so different in Perth. One of the first things I noticed was that there weren’t lots of people everywhere. It wasn’t exciting, noisy, vibrant, and nearly all the people were white people, but they didn’t wear uniforms, and they sounded strange when they spoke. Their accents were so very different from the way my parents and the other Officers and their Memsahibs used to speak. But they spoke English, and I could speak English, because my parents wanted me to.

The North Perth Hotel was an old Victorian building that was typical of much of the older Perth architecture. A corrugated iron roof, painted brown, or perhaps rusted brown, but the effect was the same. Deep verandas at ground level and also on the first floor.

Downstairs, off the street, there were several entrances; several leading directly into the bars downstairs. When we walked past we could smell the beer. Everybody seemed to be drinking beer all the time. There were, as I found out very soon, bars which were for men only. Ladies were discouraged from entering, and I am sure that few would have wanted to. Daddy said that the bars were a “male domain” which meant that men used to go in there to show off, I think, but Daddy didn’t like the way the men behaved in there. There was also a small room inside, called a “Ladies’ Lounge” where ladies would meet with their friends and drink Swan Lager from schooners

Hay Street, Perth

On the first day in North Perth, my parents had gone to look in the windows of the local shops. They took me with them and we stopped at the first shop, which was opposite our hotel.

When she looked in the windows of the shop, Mummy had been amazed at the piles of confectionery and sweet things there.

Not only on the bottom of the window, and on shelves, but strung along the top of the window, on thin white cord, were white and red walking sticks…as big as Daddy’s hand, as thick as Daddy’s thumb… bright red and snowy white striped walking sticks… I gazed at them. What beautiful decorations

“But no chocolate!” My mother was triumphant as she gave this information to my father.

“There are so many sweets… but no chocolate”

This seemed to make it better. Auntie Lyszod, in Wales, had to use her ration book to get chocolate… and here… but the look of triumph; the look of satisfaction fell from her face as we entered the shop; for there in the front shelf of a refrigerated display; just behind and under the counter, were rows of chocolates and rows of chocolate bars. There was a huge block of milky looking ice at either end, inside the glass case and the glass was cold and wet when I touched it.

When we lived in Colchester with my English Granddad, Mummy made an Easter Egg using cocoa powder and sugar. She cooked it all together in a little saucepan with some milk and butter and when it was runny she poured the hot chocolaty stuff into two big serving spoons and when they were cool and hard, she stuck them together to make an Easter Egg. I was the only boy at school who had one, but I wasn’t allowed to tell anyone, because they might tell someone else.

That was like when Mummy bought some parachute silk which an American man had and she made me a shirt out of it. I looked very Posh, because Granddad said so, but because it was against the law to have parachutes, I wasn’t allowed to wear it outside and show my friends… in case Mummy and Granddad, and maybe I, would have to go to prison.

But I didn’t see any jelabies or gulabjamin in the shop. There were no Indian sweets, just strange sweets I had never seen before. And nearly all of them were wrapped up in silver paper and paper and they had writing on them to tell you what was inside.

Hay Street, Perth, with electric trams.

Rationing was still in force in Britain and of course, sugar was included… yet here, almost obscenely, were piles of sweets in the windows of the shops… pale bleached pink, green and white marshmallows, and liquorice, and toffees…toffees oozing their thick liquid from inside their wrappers, down the inside of the glass in the late West Australian sunshine.

And down in one corner, lying on his back, with his legs in the air, was a dead fly. Maybe he ate too may sweets, or he was very old, and he just died there.

Mummy said that Auntie Lyszod in Wales had suffered, along with the rest of the United Kingdom, through rationing. Sweets and chocolates were a luxury, and the Ministry of Food had burdened the country with ration books and dictated that everyone should tighten his belt as we had just been at war.

I couldn’t see how tightening your belt would make you not want to eat sweets, but parents and other grownups say strange things sometimes.

Yet Auntie Lyszod and the rest of the family hadn’t suffered as much as those people who were living in the cities.

I know, because my Mummy and I had been in Wales for a while when my Mummy and Daddy were angry with each other, and my Mummy had gone back to look after Mamgu, my grandmother.

We weren’t as unlucky as some people about the Rationing because my Uncle Rees was a farmer and he had seven cows and a bull, so we always had enough milk and butter, and there were chickens in the garden at Brynteg House, my mother’s family home. We even had pigs and although we were supposed to notify the Ministry of Food or something, about the pigs, and hand them over to be slaughtered when they were big enough, I am sure that this was never done.

I had three pigs altogether, but it was sad what happened to them so I won’t explain about that here. It wasn't very nice and it makes me sad to think about it.

But that was long ago, and I can’t remember lots about being in Wales, except being able to sit in Mamgu’s lap in front of the big black range in the kitchen, and the fire made us lovely and warm. Mamgu was soft and cuddly, but outside was always wet and cold, and there were little bits of words from newspapers when I went to the lavatory. Just a word here or there in the lavatory paper, but it didn’t make sense. There wasn't a story; just odd words.

Auntie Lyszod said that they made newspaper back into lavatory paper when people had read them, and that’s why the words were there. There were words in English, and I could read them, because I could speak English and I could read in English, but when I was at school and playing with my cousin Morlais, I used to speak Welsh. Mamgu said I spoke Welsh better than a Welshman.

When we were in the shop, my father bought me a pink and white walking stick made of sweet peppermint, and for each of us: for my mother, for me, and for himself, he bought a white paper bag. The bag was folded to make a triangular shape and out of the corner of the bag; out of the apex of the triangle, stuck a short, white paper straw.

He handed one to me, and I felt a soft weight in the bottom of the paper bag, the sharp corners if the paper, and the soft belly that held something soft. He raised his bag and, putting the straw to his lips, drew on it, and then indicated that I should do the same. I brought that straw to my lips.

“Suck it,” said my father, and his eyes were smiling as I seldom saw him smile, “Suck on it. It’s nice.”

I sucked deeply and an explosion of taste and pain hit my eyes, the inside of the back of my nose, my palate. I coughed and spluttered, and laughed. My nose was wet; my eyes streamed; my scalp felt as if I had received a whack from inside my head, Yet I laughed and spluttered some more.

“Sherbet,” he roared, “That takes me back. I haven’t had sherbet since I was a boy.”

My father bent forward and slapped his knee with his left hand, the right, containing his bag, spilled white powder over the ground.

When we went out for the day to look at our new surrounding; our new home in a strange country, my mother made me leave the remains of the stick of peppermint I had been sucking. I left it on the dressing table by the window.

We were out all day. But when we returned to the room late in the afternoon, my piece of peppermint stick was no longer striped red and white, but brown with tiny crawling ants. It looked like a long brown cushion that was just slightly moving as if it was breathing.

I remember being in the North Perth Hotel, and the little army of marching ants that climbed from the wall and the floor.

The wall seemed to have ants moving all over it. Directionless. Scouts, perhaps of a larger party. If I had looked closer, as I had learned, or would learn to do later, I would have seen that each of these seemingly randomly wandering insects had a purpose, and that they exchanged information with each and every other ant they came across, assumed formation in a long line that climbed up one of the legs of the dressing table. There were dishes in which the legs of the dressing table stood. Little, thick china dishes, or were they glass? As big as the almost closed palm of a grownup’s hand. There had been water in these; once. There was still the crust of what once had been water. Now, just a mixture of crystalline deposit and dust and dead ants ......and the army of ants flowing, marching over their defunct comrades.

My mother complained to the owner of the Hotel.

“We never had this sort of thing in India,” she protested.

The owner, the little manager, looked at my mother. He picked up one of the tiny insects and crushed it between his index finger and his thumb. Then he brought his fingers to his nose and smelt them.

He turned his head to the side, looked to the ceiling, sniffed his fingers again and then wiped them on the sleeve of his jacket.

Then, with a deference or politeness born more of boredom than of manners, offered a vague explanation.

“They are argentine ants, Madam,” he said dismissively. And for him that was good enough. Argentine ants… Therefore nothing could be done.

Argentina

Argentina. Just the word, drew pictures in my mind.

When we had lived in Dehu Road, on the Bombay Poona Road, there had been newsreels at the cinema. Grainy newsreels of strange people who walked very quickly. Men in strange uniforms. Uniforms like the men in funny films… black and white pictures of men in uniform… But where we were in Dehu Road, was the India of the British Raj, and in that India, all the white men were in uniform. The uniforms there were khaki, and the men, like my father, the officers, looked very much the same as the other men. The only difference was the officers had stars and emblems on their shoulders to show that they were different. But these men wore white and silly uniforms. I had seen the men on the cinema screen, and I had pieces of their pictures in my OXO tin.

Argentine ants… Those words reminded me of people driving, driving in big black cars, at speed, through streets filled with people. And the people were all shouting. And the men were walking so quickly. And a lady with blonde hair, among all those men with their sleekly oiled heads. And the lady with the blonde hair was raising her hands like a china doll… like the beggars in the streets of Poona. Like the little girl in the doorway outside the big shop in Poona… the little girl without any feet.

I loved that cinema. We went once a week and watched films about ladies and men who sang to each other. And newsreels about “Snow in Blighty”, and newsreels about people running through the streets in Bombay and the lady in Argentina who shouted and looked happy and angry all at once… and she held both her hands in the air like a doll.

Binkie Taylor had a doll that held her hands just the same way as the lady in Argentina. I saw the doll when we went to visit Binkie Taylor’s Mummy and Daddy once. She had left the doll on the veranda and I saw it with its hands up in the air, sitting on its own little cane chair.

And sometimes, sometimes the film stopped and a white hole with a bubbly black circle around it came on the screen, and then we all had to leave our seats and go outside and all the Indians started shouting and laughing and whistling because the man in the projection box had gone to sleep and the film had caught fire again.

And the films would go on and on and I usually went to sleep towards the end. And at the end there was a bit when we all had to stand up and listen while a lot of Indian people on the screen sang “Jai Hind, Jai Hind” and they all looked happy and laughing and the Indian flag came next... And I stood up very straight. I stood up very straight because that India flag was my flag, because I was an Indian, and I was a Baluch, and the song was about my country.

“Jai Hind” means “Great India” or “Victory to India”, and I used to sing it deep inside me, even when I was walking by myself.

And Daddy and Mummy stood up as well, but Daddy looked a little bit cross, and sometimes I could see he was crying a little bit, just a little bit, but I didn’t know why.

And then everyone clapped, and after that, we went home.

And Bearer and Khansama taught me to say, “Jai Hind” which also means, “Hello”, and put my hands together, and I wasn’t to say, “Salaam,” when I met anyone, any more.

Bearer’s name was Krishna, and I loved him even more than I loved Mummy and Daddy, I think.

Then, after a while, we all went back in and they turned the lights off and the film started again. I loved sitting there and imagining that I could fly over the tops of the people and then they would look up at me and not bother about watching the films. We always sat upstairs and the Indian men and ladies sat downstairs. I can’t remember many ladies, but the men made a lot of noise and they laughed at all the funny bits.

Next day, I would go to the back door of the cinema, and in a big black iron drum near the door, I would find bits of the film that had caught fire the night before. And my friend, Lal, the projectionist, who had gone to sleep and let it all happen, would let me take bits of the film home with me... if I asked nicely. And they smelt bitter, but you could see the ladies and the men who sang to each other… and once, only once, I found a picture of Mrs Peron in a white fur jacket… and she looked so pretty… even though she had lines between her teeth in the newspaper photographs. And I put it with the other bits of cinema film, in my OXO tin. But I lost it; I lost the picture of Mrs Peron in the white fur jacket, although I didn’t lose the pictures of the men in uniforms like the men in funny films… black and white pictures of men in uniform.

Little sections of transparent film with black and white pictures of foreign men in a foreign country.

And I had been given those pieces of film when I had gone to the cinema in the day time, when I went out with Krishna, or when I just walked to the end of the road where our bungalow was at number fourteen.

The cinema was very close to the swimming baths and just on the corner was a big stone platform where they used to have funeral pyres, and at one end, there was a little platform where the wife of the man would stand when her husband was being burned. Krishna told me that a long, long time ago, the lady would jump onto her husband's burning body on the funeral pyre and that was dreadful.

I asked Krishna why, and he said, “Because.”

The paper bag that had contained the sherbet, the triangular paper bag that I had torn apart, the straw through which I had sucked the sherbet… I had torn that bag apart, licked off all the sherbet, and there it now lay, in the wastepaper basket beside the bed, and the ants feasted on the paper. Had I left any of the sugar, the sherbet? Argentine ants. The lady’s name was Mrs Peron… Eva Peron. Peron. Driving through those streets, and the vast crowds waving and laughing and shouting. The lady on the balcony with her hands in the air, shouting at the crowds below. That was why they couldn’t be stopped. Argentine ants. The lady on the balcony. The fast cars.

The man letting himself drop down from the frame of a blown out window in a foreign city. The burning pieces of cloth or flags and photographs in the street. The old lady crying and walking towards the camera.

Argentine ants.

Argentina.

Argentine ants. It seemed logical to me. It still does.

Give it a name, and there the explanation must rest.