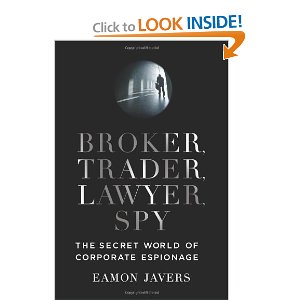

Broker, Trader, Lawyer, Spy: A Book Review

We're going to take a look at a book by a reporter for Politico, called Eamon Javers. As you can see from the picture, the book is titled: Broker, Trader, Lawyer, Spy: The Secret World of Corporate Espionage, published in hardcover by Harper, 2010.

In another hub....

http://wingedcentaur.hubpages.com/hub/More-on-the-Capital-Surplus-Absorption-Problem

.... I talked about how instructive it can be to read certain books in pairs. The example I gave -- and which, indeed, provided the focus for that hub --- was two books by a journalist specializing in economics called David Cay Johnston: Free Lunch: How The Wealthiest Americans Enrich Themselves At Government Expense (And Stick You With The Bill). Portfolio (Penguin Group), 2007; and Perfectly Legal: The Covert Campaign To Rig Our Tax System To The Benefit Of The Super Rich --- And Cheat Everybody Else. Portfolio, 2003.

The Free Lunch book is about how, since 1980, America's corporations have, apparently, NEEDED more and more government SUBSIDIES to sustain themselves. The Perfectly Legal book is about how America's corporations and wealthy people have upped the ante on TAX EVASION since 1990.

As I discussed in the aforementioned hub, those two books, together, give me a picture of what's been happening to the American economy since 1980. Mr. Johnston doesn't, to my knowledge, interpret his findings the way I do, but I see a connection between the two books. Indeed, one books seems to explain the other.

Why has there been an increase in tax evasion among the wealthy and corporations since 1990, as discussed in Johnston's Perfectly Legal book? Precisely because of business's increased dependence upon and getting of government subsidies since 1980 --- monies, which, because of their very nature, cannot be reinvested in production, as paradoxical as that sounds. And we learn all about corporate America's increased reliance on government subsidies in Mr. Johnston's other book Free Lunch.

Now then, as I may have mentioned once or twice before --- in my view --- the modern (monopoly) corporation is simply too big to be sustained by straightforward market forces alone. I mentioned, before, that these organizations function much like the Borg cubes on Star Trek. You know the Borg? They can only survive by absorbing and assimilating other people, cultures, and technologies. The Borg CANNOT simply 'live and let live' and leave everybody else alone.

The nature of their being requires that they engage in brutal violence against others in order to survive. Capitalism is a political-economy in which the competitive pressures it inflicts prohibits companies from just remaining small. If you just try to hold your own, you might get 'swallowed' up by a competitor, a bigger fish in the sea and so forth.

Therefore capitalism is driven by constant expansion in this way. But this expansionary force creates business organizations, corporations, that are fundamentally unwieldy entities. In other words, in my opinion, these corporations cannot possibly sell enough stuff to enough people (its not just the notorious auto industry) to sustain themselves in their gigantic incarnations, therefore they need things to prop themselves up: government subsidies, government tax breaks at the state, local, and federal level, tax write-offs and rebates (whether legitimate or dubious), tax evasion, stock market speculation, and so forth.

Furthermore, it is for this reason, I think, that corporate chiefs and their Republican spokespeople are always complaining about corporate tax rates being too high. The truth is that corporate taxes could never really be low enough to satisfy them, because the corporate boards of the world's largest multinational businesses feel as though they are constantly in a position of having to 'bail water,' as it were from a huge, mighty looking ship that nevertheless has a big hole in the side. Follow me? Good.

Also, when corporations expand in a Borg-like way, through mergers and acquisitions, leveraged buyouts (hostile takeovers) and the like, this activity should be understood as a kind of defensive measure on their part: to position themselves to command dwindling markets and resources and therefore profits. For example, say there's six of us on a life raft. We're stranded in the middle of the ocean with, say, a week's provisions left. Now suppose there is some doubt about someone finding us in a week. Two of us get together and think to ourselves: 'Six of us, one week's provisions, two of us, three week's provisions. We'll live longer.' So, the two of us kill the other four, extending our chances (the two of us) of survival and rescue. The point is that we get rid of 'too many competitors' in the 'market.' In order for corporate capitalism to 'work' (for anybody, as it were) there must not be too many competitors in the market.

In such an environment of defensive corporate expansion --- again, which has accelerated since around 1980 --- information becomes even more crucial than it had been before. This leads us to conceive of a phenomenon we might call the increasing paramilitarization of business that has occurred since, say, the fall of the Soviet Union in 1989/90. That is what Eamon Javers's book, Broker, Trader, Lawyer, Spy (2010) points to.

Now then, big business has always had what we might call a 'paramilitary' component just about from the beginning of capitalism itself. This is a major point that the author, Mr. Javers, would have us understand.

For example, consider the world's most famous banking family, the Rothschilds. It seems that the family's material prominence dates back to 1744 with the birth of Mayer Amschel Rothschild in Germany. Mayer was the founder of the family's banking empire. He had five sons. Mayer Rothschild sent each son to a different European capital to open up a branch of his own. One son went to France, another to Italy, another to Austria, and another remained in Germany (Javers, p.25).

Mayer's son, Nathan, was based in England, and by the 1820s was prosperous enough to lend money to the Bank of England, helping to head off a potential economic crash in London (ibid).

Eamon Javers wrote: "From the earliest days, the Rothschilds understood the importance of combining finance and intelligence. Nathanial coordinated high-stakes deals with his four brothers on the continent, who were based in France, Italy, Austria, and Germany. Through couriers, clients, and confidants, they developed an elaborate intelligence network that spread across Europe. Nathan Rothschild arranged for money to be shipped to the duke of Wellington's armies during their epic battle against Napoleon. In 1815, Rothschild knew of Wellington's spectacular defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo an entire day before the British government itself was informed" (ibid).

So, big business's reliance upon intelligence operations --- which, during this historical cycle, has increased dramatically since 1989/90 with the fall of the Soviet Union --- is what I mean by the increasing paramilitarization of business that Eamon Javers's book points to.

We are talking about the private spy business --- that private spies as opposed to private soldiers like Blackwater and the like. There are probably hundreds of private spy firms located around the world. Corporations, financial institutions, and rich people can hire private intelligence outfits in Britain, America, Europe, and the Middle East. And theres a wide menu of options to choose from. One might hire firms staffed by ex-FBI Special Agents, ex-CIA officers, ex-Secret Service Agents, ex-British MI5 officers; and there's even a firm staffed by ex-Soviet KGB officers and military intelligence officers, located in suburban Virginia, not too far from CIA Langley headquarters (Javers, pp.x-xi).

Now then, Mr. Javers put in a nutshell, the precarious global situation, which, from the perspective of business, requires corporations to arm themselves in this way.

"Even as it remains a largely hidden industry, the private spying business is becoming an integral part of the way companies do business around the world. The past several years have made it abundantly clear that there are far more hidden, and dangerous, secrets at work in the global economy than even many sophisticated businesspeople once thought. For nervous financiers and executives, ramping up private intelligence capability is an understandable response to the confusing and sometimes deadly situations that surround them. The global economy is a paranoid place" (ibid, p.xiii).

From my perspective, though, I'm not too sure about the "confusing and deadly situations" business that Mr. Javers alluded to. I did not come away from reading his book with the feeling that the world of business had become anymore deadly (if you want to think about physical danger to executives) in the post-Cold War world than it had been in the old days. I did get the distinct impression that the major corporations avail themselves of private intelligence services in order to get a strategic advantage over their competitors.

In addition to that, one comes to understand that the use of intelligence operations are a vital and hidden, most of all, ingredient in the success of many, perhaps all of the major corporations, which, in a sense, gives a bit of a lie to the idea of merit, hard work, and the 'free market' as the driver of national economies and the global economy.

For example, let's consider defunct energy company, Enron. Enron's story is well known by now. The organization had spent years lobbying Washington to deregulate energy, which would allow anyone to buy and sell electrical power just like any other commodity. The organization's chairman, Kenneth Lay, had a good relationship with then-President George W. Bush, and Enron made seemingly massive, record-breaking profits, and so forth (Javers, p.17).

But Enron had its own in-house staff of former government intelligence agents. This in-house staff hired another private intelligence firm called Diligence. Diligence provided assistance in vetting companies that Enron wanted to acquire. That was one thing Diligence did for them (ibid).

But, in short order, Enron's in-house intelligence unit came up with a much more ambitious idea. Enron's trading unit could bring in more money for the organization, if they could know in advance when power plants would be shut down for maintenance. Power plants have to be shut down periodically for inspections and repairs. This is done at regular intervals but not always with public notice (ibid).

When power plants are taken offline, sometimes for days at a time, the price of electricity in an entire region can go up, you know, due to 'supply and demand.' If Enron's traders had a schedule of plant closures they could make winning bets in the energy markets based on the almost certain knowledge of when electricity prices would rise, by how much, and when it would happen (Javers, pp.17-18).

Enron's in-house spies made a proposition to Diligence: Please tell us when the power plants would be going on and off. The in-house spies had already made a checklist of things a plant might do before shutdown: let its supply of coal run very low; since the maintenance would need specialized employees, the plant owners are likely to bring in portable toilets and other amenities; and since all the new workers will need a place to stay, local hotels might be booked to capacity during the maintenance (ibid, p.18).

What Diligence ended up doing was overflight surveillance of Europe's biggest power plants, perhaps in the Netherlands, France, Germany, among other places. They put together a pattern and relayed the information back to Enron. This information (gathered in a perfectly legal way, as a matter of fact), nevertheless, gave the energy giant a "crucial edge over the rest of the traders in the market" (Javers, pp.18-19).

Let's back up a step

Remember I said to you (whoever 'you' may be) that in an environment of corporate defensive expansion --- which, as I said, is based on corporate moves to try to secure the lion's share of dwindling markets and resources --- puts an even greater premium on information-gathering.

In this hub.... http://wingedcentaur.hubpages.com/hub/Clark-Where-Have-You-Been-Or-The-American-Disconnect-Between-History-and-Law .... I talked about the leveraged buyout mania that took off in the United States in the 1980s, and largely fuelled the bull market of the 1980s and 1990s. The economic phenomena that led the way to this kind of thing is what is referred to as the financialization of the American economy, which got started in the 1970s.

We don't have to go over the details of financialization here. Just understand that what we're talking about is a deregulated, hyper-energized financial system relative to a relatively hum drum real (productive) economy. Now then, the latter (real economy) CANNOT possibly turn over enough profit fast enough to satisfy the demands of the former (the deregulated, hyper-energized financial system).

Therefore, the only way that the seemingly insatiable, vampiric hunger of the financial system, as a whole, is by engaging in quick and dirty, though legal, predatory operations such as leveraged buyouts.

Let's remind ourselves, very quickly, what a leveraged buyout is; and then we shall see what it has to do with information-gathering networks.

First, you need a corporate raider (this is the term that came in vogue in the 1980s).

Second, the corporate raider targets a company that is a good takeover target. This is a company whose financials show that it can bear a good deal of weight in the form of debt. This is a company whose break up value is more, in the short term, than its present total value as a whole entity. Think of it this way: a car thief steals a car, not for his own personal use, and not because he wants to resell the car as is. No, he believes it would be more valuable for him to break up the car and sell it for parts: the steel-belted tires, the stereo sytem, the GPS, and all the electronic apparatus that modern cars are loaded down with these days, and so forth. So, the car thief will take the car to a 'chop shop,' I believe the term is, to break the car up.

Third, the raider sets up a shell company. This is the hollow entity that will receive the acquired company.

Fourth, the corporate raider borrows the money he's going to use to buy the targeted organization. The raider borrows the money from banks, who agree to be party to this operation because the raider promises to pay them an unusually high rate of interest.

Fifth, the raider starts quietly buying up all the outstanding, available shares of the targeted company. Then the raider makes an offer to the board of directors for the rest of the shares.

Sixth, if the raider is successful, he gets the company. It gets incorporated into the shell company, and the debt that the raider took on to fund the enterprise --- is transferred to the acquired company.

That debt is now somebody else's problem.

Now, the new owners of the company will use the acquired company's own resources to pay off the debt (which the raider took on to fund the acquisition). They will do everything they can think of: bargain down wages of workers (playing 'hardball' if necessary), laying off workers, selling off equipment, move production overseas (this is what the Obama campaign is accusing Mitt Romney's firm, Bane Capital, of having done, which is just one of many tools private equity firms utilize).

The point is that corporate raiders do not work alone. Networks of risk arbitrageurs (by the way this is a word that seems to have several uses) are involved, who are constantly on the lookout for the next takeover opportunity, substituting conventional measures of a company's value for something called private market value.

Private market value is calculated on the basis of how much 'free cash flow' a company generates and how much debt it can support.

The arbitrageurs act in a kind of unofficial collusion, as they search for vulnerable companies and take large stakes in them, thus putting them 'in play.' When a bid is publicly announced, the raider's broker only has to call up all the members of the arbitrage club (none of which has any personal loyalty to the targeted company), have them turn over their shares to him, said corporate raider, so that he (the raider) can gain control of the company.

As I alluded to the "Clark, Where Have You Been..." hub, this process is known as a street swap; and this is, roughly, how Robert Campeau had taken over Allied Stores. With a single telephone call, a broker named Boyd Jefferies acquired thirty-two million shares, or more than half of the shares in circulation, thus giving Campeau control of the $4 billion company.

The end result seems to be one of two outcomes: Either the acquired company can withstand the 'austerity,' let's call it, of everything the new owners do to pay off the debt --- in which case the 'streamlined' company is put back on the stock market; or the acquired company is not strong enough to withstand the 'austerity' and are driven to bankruptcy.

Interesting Sidenote

What we see is that, starting in the 1980s, corporate finance learned how to use debt as a weapon, a kind of battering ram.

Apparently, debt was also used as a kind of shield. It seems that, in response to the leveraged buyout trend, companies sought to protect themselves by preemptively loading themselves down with debt so as to make an unattractive takeover target for corporate raiders (1).

My point --- in this hub which is a book review of Broker, Trader, Lawyer, Spy by Eamon Javers --- in revisiting the issue of leveraged buyouts, is to link this with Mr. Javers's sidenote about the Rothschilds of the eighteenth century. The point is that big business has always, since the beginning of capitalism, seen the value of information, specifically, of getting it first. To this end, the business community has always sought to devise methods and networks (often very effective) in order to get this information, whatever it might be, in a timely fashion.

The use of private intelligence firms --- these days, since the end of the Cold War --- is professionalizing these processes.

Disclaimer: I really feel that I should tell you that, just as David Cay Johnston (journalist and author of Free Lunch and Perfectly Legal), does not --- as far as I know --- interpret his findings the way I do, as signalling a long-term crisis of capitalism: corporations, since 1980, have become more and more dependent on government subsidies and tax breaks to sustain themselves, which, as I see, is the very explanation that corporate tax evasion has been on the increase since 1990; big business, through use of their political power to produce a 'profit' which cannot be reinvested in production and expanding the business and employment --------- just as this is the case with David Cay Johnston, this is also the case with reporter and author Eamon Javers. As far as I know, Mr. Javers does not interpret his finding the way I do. He does not, as far as I know, share my particular analytical framework.

Again, my thesis is: Certain books, read together, give us a coherent picture of what's happening in the political-economy. As corporations (unwieldy, gargantuan, monopolistic entities- the major ones, anyway) have become more and more dependent on government subsidies and tax breaks and other favors (since they cannot possibly find enough people to sell their products to to sustain themselves at their present size, they have increased both their tax evasion, and their corporate representatives and the Republican party have increased their whining about corporate tax levels, which, from their perspective, can NEVER be low enough because the corporations constantly feel as though they are bailing water from a mighty, seemingly invincible ship, which, nevertheless, has a big hole in the side.

This being the case, corporations engage (more and more since the 1980s) in massive consolidation, 'defensive expansion,' because they want to put themselves in the best position to command dwindling markets and resources. This being the case, then, corporations place an even greater premium on information, getting it first, which brings us to Eamon Javers's book Broker, Trader, Lawyer, Spy: The Secret World of Corporate Espionage (2010). As far as I know, Mr. Javers does not interpret his research the way I do.

We have come all this way, dear reader, and still I feel as though I've barely scratched the surface of what I wanted to say. Let me just wrap up this essay by saying that: Mr. Javers's book, Broker, Trader, Lawyer, Spy (2010) is a very, very, very (That's three veries!) important book for several reasons.

1. This book is important because it was written by a very mainstream reporter/author. I know Eamon Javers is mainstream because he makes regular appearances in the weekend news roundup show on PBS called Washington Week (with Gwen Ifill). Despite the station's assertions to the contrary, it doesn't get more mainstream than PBS.

2. As a mainstream writer, Eamon Javers has provided us with an important, hidden ingredient in the way power functions (in the United States in particular, and other places most assuredly). With Broker, Trader, Lawyer, Spy, we are acquainted with the stealth techniques that powerful/rich people utilize to war with one another and try to gain advantage over the other guy. Some of the (private) intelligence mechanations some of the characters in this book get up to, as described by Mr. Javers, used to be the almost sole province of the so-called 'looney left conspiracy theory' crowd.

3. In opening up, to the broader public with this book, the stealth techniques used by the rich and corporate set, as Mr. Javers does, we (the broader public) are allowed to see that there is almost no lengths that the upper corporate sect will not go to, to get the advantage over their rivals. Moreover, there is almost nothing too silly for them to engage in expensive, clandestine duels using their privatized intelligence cadres.

For instance, Mr. Javers tells an amusing story about what we might call 'The Great Chocolate War' between Nestle and Mars. Javers explained that in late 1997 the two massive conglomerates were at war over a product put out by Nestle: something called Nestle Magic, "a two-inch chocolate candy ball encasing a plastic shell that in turn held a small Disney-themed toy."

From the get-go Nestle did have problems with the promotion. The FDA had already warned Nestle that this product ran against the grain of a decades-long law which banned the combination of food and toys. But Nestle was satisfied that they had tested the product thoroughly and, they argued, the Consumer Product Safety Commission had signed off on it. The leadership of the company believed that their disagreement with the FDA was a minor technical point, which could be ironed out easily enough. Nothing would derail the launch of Nestle Magic!

Nestle signed a contract with Whetstone Candy, a family-run manufacturing company based in Florida, to actually produce the physical product. Now, remember that name, folks, Whetstone Candy --- this will be important to an interesting little twist that happens later.

Nestle began selling the candy in July 1997 and they sent marketing materials around which said, "The power of Nestle. The excitement of Disney." The product was hugely successful intially, flying off store shelves.

Apparently, the toy-chocolate combination represented the Holy Grail of the industry. "Whoever gets the toy-chocolate combination right," said one person involved with the operation, "they've got the holy grail."

But things started to go wrong. Complaints were being heard about toy-candy from critics all over the country, at federal agencies, on Capitol Hill, and in the offices of consumer groups. Indeed, "[e]ven the Centers for Disease Control and the state attorneys general in Minnesota and Connecticut registered alarm."

To the executives at Nestle, this swarm was almost overwhelming, and seemed to them, like a coordinated attack. But they did not know from where it was coming. Just to put the proper frame around this situation, let's just quote the author again: "In the candy business, a victory for one company often comes at a direct cost to another. Suddenly, Nestle Magic was making Mars market share disappear. Nestle suspected that Mars was behind the sudden flurry of complaints about the new candy."

Now follow me. To check out their suspicions Nestle hired Kroll Associates. They investigated the Mars Washington team, gathering background information, addresses, media clips, and some Social Security numbers and children's names. They looked into the lobbying firms involved, pulled the records of campaign contributions from key officials, and noted which people involved with Mars's effort had gone to the same schools, which were old family friends, and which were former colleagues.

Kroll then sent a report, outlining their findings along with advice on how to combat the Mars effort, to the Nestle legal department. But it was too late. The FDA granted a damning interview with the New York Times about Nestle Magic, which made it all but impossible for the company to market and sell the product. William Hubbard, the associate commissioner for policy at the FDA said, 'This product is illegal under our act.'

That was the end of Nestle Magic. Nestle sent word to Whetstone to shut down operations. Whetstone would soon find itself involved in a long legal struggle with Nestle about who was to be liable for the costs of the new manufacturing facility, now sitting idle. Nestle actually hired spies to go down to the facility in Florida to find out if Whetsone was using the factory to produce candy for the enemy: Mars.

But wait, that's not the end of the story. Nestle wanted to find out exactly what had happened in the defeat of Nestle Magic. First, Nestle hired a firm called Beckett Brown, which set up a surveillance of a small consulting firm called the Hawthorn Group. The Hawthorn Group is closely associated with Mars.

The former Secret Service agents of Beckett Brown decided to target a man called Richard Swigart, a consultant with Hawthorn, with a very particular purpose in mind.

You see, there had been a shadowy operative, working on behalf of Mars, who had thrown the monkeywrench into the Nestle Magic project. That operative had called himself 'Deep Chocolate.' Yes, Deep Chocolate.

They went the whole route in putting Swigart under surveillance. First, Beckett Brown hired a small private investigative firm in New York to get access to Swigart's home phone records. That agency is called Science Security Associates, Inc. Science Security was able to get Swigart's records on his AT&T service from November 1997-January 1998. Beckett Brown also got hold of the man's financial records.

The results of their investigation satisfied Beckett Brown that Richard Swigart had, indeed, been the notorious Deep Chocolate.

Eamon Javers wrote: "Working as a subcontractor for Hawthorn Group, which in turn was working for Mars, Swigart was one of the leaders of the covert effort against Nestle Magic. As part of his campaign, Swigart reached out to consumer groups, government agencies, and the media, making the case that Magic was dangerous and noncompliant with the FDA's rules. And even though Swigart had spent a career as a corporate consultant working against consumer groups like US PIRG, he needed to work with his old enemies on this operation. He dropped off packets of information against Magic at the offices of various consumer groups."

Beckett Brown also investigated a law/lobbying firm, Patton Boggs, that also worked for the Mars corporation. And so on and so forth.

A lot of other stuff happened...... and we're moving on.

After Nestle recalled Magic, the people at Whetstone, their subcontracted manufacturer, kept on working on the product, knowing that if they could modify it enough to get it through all the federal regulatory hurdles, Magic could make them, Whetstone, millions of dollars, based on how well the product had sold before.

Whetstone developed the product for a toy and candy combination that would meet the FDA's safety standards. They pitched the idea to Nestle's, who turned it down. Nestle had lost too much money on the project initially to put anymore investment dollars into the scheme.

After some initial resistance, which Whetstone was sure was coming from Nestle, the product nevertheless managed to pass the government's regulatory review this time. The safety commission concluded that even though the chocolates were encased in rigid plastic eggs that contained paper toys, they were not hazardous.

Whetstone christened their product Megga Surprize, and Nestle --- ironically enough --- had used the same clandestine tactics against their former contractor that the Mars corporation had used against Nestle. The product hit store shelves but, in the end, did not work out too well (2).

One major point to take away here is this: Corporations have a more nuanced view about regulations than is often portrayed in the media. They don't mind regulations --- for everybody else. And, if you set yourself up in a tactical way, you can use regulations (or invoke them) as a weapon to bludgeon your competitors.

Also, Chapter six of Mr. Javers's book, "The Chocolate War," also talks about another business struggle between Nestle and Mars concerning the global pet food market and all that. Anyway, it seems that Mars got up to their old manuevers, more or less. At one point Mr. Javers wrote: "As Nestle discovered, Mars was mounting an operation very much like the operations companies around the world conduct when they calculate that it is easier to lobby governments to block their competitors than it is to compete in a free market. It was, of course, possible for Mars to undertake a free-market offensive against Nestle, perhaps rolling out newer and better pet food products, or slashing prices on existing products. But that would require time and cost an enormous amount of money. It was far simpler and cheaper to manipulate European governments to think it was in their own interests to block Nestle's aspirations. Getting government help can be vastly more rewarding than anything many companies can do in the private sector. That's one reason, for example, why they spend so much money lobbying the U.S. Congress for earmarks --- those special, targeted, spending provisions often stuck into legislation moving through the Capitol. In 2005, on average, companies recieved as much as $28 in earmark revenue for every single dollar they spent on lobbying expenses. That's a much better rate of return than many could get producing and selling products" (Javers, pp.159-160).

And, for those of you familiar with the capital surplus absorption problem, remember that the $28 dollars in earmark revenue is 'profit' that CANNOT be reinvested into factory expansion and expanded employment because this money DID NOT come from production!

4. Another reason Eamon Javers's book, Broker, Trader, Lawyer, Spy is important is because he touches upon the historically constant intertwining of so-called private and government intelligence operations.

For example, remember the small private investigative agency in New York, called Science Security Associates, Inc? They were an agency that was subcontracted by Beckett Brown in their 'Deep Chocolate' investigation for Nestle. In a footnote Eamon Javers noted a connection this firm had to the Watergate affair in the early 1970s.

In the months leading up to the break in, an operative working for Science Security, James Woolston-Smith, somehow learned of plans being worked up by the Committee to Re-elect the President (CREEP). A veteran CIA officer, George O'Toole noted what happened next in his 1978 book, The Private Sector. O'Toole said that Woolston-Smith passed on his information to a former client, William Haddad. Haddad told the Democratic Party chairman, Larry O'Brien: the names of the people who were to be involved including James McCord and G. Gordon Liddy (Javers, p.151).

I'm quoting Javers, who quoted O'Toole: 'It seems incredible, but nearly two months before the arrest of McCord and the four Cubans inside the Watergate offices of the DNC, the Democrats had been fully briefed on the CREEP operational plans to bug them.' It was never clear how the Science Security employee got his information (ibid).

Even more interesting than that --- and I'll close with this --- is a private spy firm known as International Intelligence (Intertel), which was known as the 'private CIA' of the reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes. Intertel was founded by veterans of Robert Kennedy's Justice Department.

Once again a snippet quoted by Mr. Javers from CIA officer-turned-author George O'Toole is in order. Talking about Intertel O'Toole is quoted by Javers thusly: "The men who run Intertel are not simply ex-cops embarked on a second career in midlife. You'll find no tell-tale bulge beneath the shoulders of their tailored, three-piece business suits, and their slim attache cases are more likely to contain pages of computer printouts than brass knuckles or handcuffs. Their clients are not retail merchants or jealous spouses, but giant international enterprises that do business under the crazy-quilt pattern formed by the laws of a dozen nations" (Javers, p.93).

Here's the interesting part about Hughes. Apparently, the businessman Howard Huges had a relationship to the CIA, many of his companies having served as 'fronts' for CIA operations over the years (ibid, p.97). Hughes had once had a 'long-serving loyal consultant' named Robet Maheu, a veteran government spy (ibid, pp.94-95).

Hughes had wanted Maheu's help in 'intertwining' his businesses ever more deeply with the CIA. Maheu told the Senate all about it in 1975, in top secret testimony before a Senate committee investigating the CIA. Hughes wanted Maheu to help him set up a massive CIA-sponsored covert operation involving one of Hughes's business (Javers, p.98).

Why?

According to Hughes, he hoped to make himself legally bulletproof in case he ran into a serious problem with the U.S. government. Hughes wanted to be in a 'too big to fail' position, so that the authorities could not afford to prosecute him (ibid).

Apparently, this is something of a tradition in corporate America and the U.S. CIA --- corporations acting as.... what? informats, deputies, or 'intelligence assets' of America's premier secret intelligence organization (3). This may be yet another hidden agreement in the success of some corporations --- a decisively non-free market quid pro quo: do some informing for the CIA and to the extent they can, Central Intelligence will assure the success of x corporation. Maybe?

Maheu refused Hughes's request.

Thank you so much for reading.

Notes

(1) see article in Monthly Review volume 58, issue 07 (December). "Monopoly-Finance Capital" by John Bellamy Foster. http://monthlyreview.org/2006/12/01/monopoly-finance-capital paragraph 10.

(2) for full story on The Great Chocolate War between Nestle and Mars, see Javers, Eamon: Broker, Trader, Lawyer, Spy. pp.137-158 & 162-166.

(3) for more on the historical hand-in-glove cooperation between the biggest players in corporate America (going back to World War One) and U.S. intelligence, see Phillips, Kevin. American Dynasty: Aristocracy, Fortune, And The Politics Of Deceit In The House OF Bush. Viking, 2004.