How the Art of Letter Writing Helped Form the New World

Genius of the biographical novel, Irving Stone brought to life in his 1965 story of John and Abigail Smith Adams, Those Who Love, the art of passionately shared written communication.

In 1965, persons still wrote letters to one another, but in the new millennium of the 21st Century the growing technology of short shouts and abbreviated messages via hand-held devices is destroying the art that once was written communication.

John and Abigail Adams

During their married lifetime, John (1735-1826) and Abigail Adams wrote hundreds of letters of devotion and communication while separated by the demands of John's career in politics and America's struggle to gain her Independence through the Revolutionary War.

Stone records Abigail's devotion in Those Who Love thusly: "When John was at home, time did not exist for her as a separate or discernible entity; it was fluid, days pouring effortlessly into nights, weeks into the months: the continuous flow of life. With John away, as he had been for three years, time became a solid; each hour was a hill, each day a ridge, each week a peak, each month a mountain range".

When the ship Boston was captured by the British on its return journey from France, John had already safety deported; however, his many letters to Abigail had been dropped into the Atlantic. Although relieved that her husband was safe, "the loss of his letters (to Abigail) was a blow," Stone writes, for "the diary of his (John's) passage and arrival in Europe would have contained sustenance more nourishing than food".

Colonial Progression and the Printing Press

Long before John and Abigail Adams solved the inconveniences of separation by continuously writing letters, The Intellectual Life of Colonial New England recorded the fact that the first colonists arriving in New England from their native land put their thoughts in print almost before they had constructed meager shelters.

Letters and writings reflecting their thoughts on leaving England, establishing relationships with the Indians and each other, and their survival in the New World were the matters upon which they debated in their hand-written communications with each other. It was soon noted that a faster and vaster way of writing was needed. Communication by letter-writing became fodder for the presses.

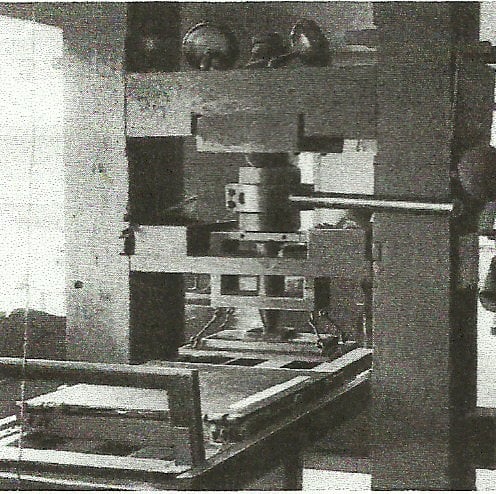

The first New England printing press arrived via ship in 1638, and within a year printing was an established business. In the whole of the English empire in 1700, Boston ranked second in the number of imprints.

English Puritans in 1630 were still unable to get their works past English censorship, and had them printed in the Netherlands, where William Brewster served as printer. However, Netherlands printers were hardpressed when political pressure caused the English Puritan churches to dissolve.

Cambridge College's Printing Operation

Cambridge become the early printing center of New England. Cambridge College's printing operation was established for all Puritans, English and American.

The Reverend J. Glover, his wife, five children, and servants; the indentured locksmith Stephen Day, his wife, son Matthew, and several sons from his wife's previous marriage; one printing press, a stock of print paper, and a font of type from Netherlands residents all crossed the ocean via the ship John in 1638. Because Reverend Glover died during the voyage, it was his undaunted wife who purchased a large house in Cambridge for the purpose of installing a printing business.

Within a year, the press was used to print an almanac and the freeman's oath. Although Day also began in the printing business, the English Civil War brought the Cambridge press into a depression, and Day wandered to other occupations, including the establishment of the New World's first ironworks.

Then came Samuel Green into the Cambridge printing world. He served as printing master for 42 years, producing a first book, The Platform of Church Discipline. In 1651, he produced a revision of Day's most successful printed achievement, the Bay Psalm Book, which was enjoyed through 27 more editions.

The Problem of Distance

New England writers preferred to be printed by presses in England, where they had the advantage of a larger market and wider audiences. But the inconvenience of distance was an irksome problem.

In the mid-1600s, John Eliot, who had established an Indian library, printed an Indian primer and the Algonkian translation of the Book of Genesis. This production interested an English Puritan missionary society that wanted to finance the printing of the entire Indian Bible. The sponsoring parties shipped to New England a press, enough type to print eight pages at once, and a young printer named Marmaduke Johnson to assist Green, who was printing Eliot's material. Throughout the middle of the 17th Century, Eliot's Indian Bible remained the most profitable part of the print business.

Notable Works of the Cambridge Press

After 1660, when English presses looked upon New England with more favor, and colonial authors were getting printed, the Cambridge press achieved reprints of some notable works, including Thomas Vincent's eyewitness account of the great London fire (1668); the Earl of Winchelsea's True and Exact Relation of the Late Prodigious Earthquake and Eruption of Mt. Etna (1669); the English translation of DeBres's Historic des Anabaptists (1668).

In 1670, many colonial works of biography, history, and poetry were reproduced, including the first bestseller in New England, Michael Wiggleworth's Day of Doom (1662). The work was created from the author's powerful dream of a Day of Judgment. Day of Doom remained the most popular book in colonial America until Benjamin Franklin's The Way to Wealth.

In 1680, Green printed the second edition of the New Testament of Eliot's Indian Bible; in 1681, for Samuel Sewall's bookshop in Boston, Green printed Pilgrim's Progress, the bestseller by John Bunyan; in 1682, another bestseller emerged from Green's operation, A Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson.

Successors to the Cambridge Press

Boston's John Foster, Samuel Sewall and brothers Bartholomew and Timothy, and the Cotton Mather family had their success in the printing industry when the Cambridge press declined as Boston printing grew.

The Mathers produced such heady works as Bostonian Ebenezer, a history of Boston (1698), and an account of withcraft, wars, and revolutions of the past decade in Decennium Luctuosum (1699).

New England Booksellers

Booksellers in colonial New England paid the printing costs and the author of a book one sum in exchange for the opportunity to reproduce the author's work. This wasn't a paying proposition for the author unless he was terrifically prolific or produced a giganticly successful single volume.

At the printer shop, the author paid the printing costs, risking loss of that amount if his work flopped. Modern day royalties help with that dilemma.

Ben Harris was one of Boston's first booksellers. His New England Primer became one of the world's bestsellers. Volumes of religion, textbooks for schools and colleges, practical works (husbandry, navigation, surveying), and home doctoring were the subjects of greatest interest in colonial America.

Hezekiah Usher was the earliest bookshop owner in Boston, beginning in 1642.

In 1700, Boston had seven booksellers, New Haven had one, as did Salem, and peddlers traveling the countryside sold to the wilderness masses. And, apparently, the masses purchased. It is recorded that at the time of his death in 1705, a peddler named James Gray possessed in cash in excess of 700 pounds, acquired presumably through his book selling enterprize.

Slow Delivery of Letters

As demonstrated by the Revolutionary War letters of John and Abigail Adams, the delivery time of hand-written letters was too slow. They sometimes arrived after the news they contained was no longer valid.

Ships across the Atlantic were relied upon to deliver letters from old shore to new and visa versa. Printed materials replaced letters as a means to exchange information of a necessary nature.

Printing presses in colonial New England continued to produce vast amounts of written material mostly on subjects for the perpetuation of life in the New World than for any entertainment. Newspapers soon took on the job of sharing popular news events.

The 21st Century

Although hand-written letters were the first form of mass communication, they were doomed from the beginning as an entity that would be replaced by inventions of speedier delivery.

And then came the 21st Century and an obliteration of not only letter-writing, but of the established art of grammar, and the need for more and more speed.

Who in the 21st Century has received a paper letter that was "more nourishing than food"?

Not LOL!?!

- Progress of Communication, or Has It?

Has communication truly progessed? Has technology progressed while skills digressed?

- Write a love letter

First of all you need to open your mind to love. Choose a quiet time when you are not going to be interrupted. Put on some romantic music, dim the lights, get a glass of wine. Close your eyes and visualize your lover's face, see yourself in their eye