Chansons de geste and the Chronicles of the First Crusade: Historiography of the Middle Ages

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Part 1:

Abstract

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Bibliographical Essay

Part 2:

Historiography of the Middle Ages

Religious and Ecclesiastical Goals of the First Crusade

Part 3:

Referenced Texts

Source Analysis

Part 4:

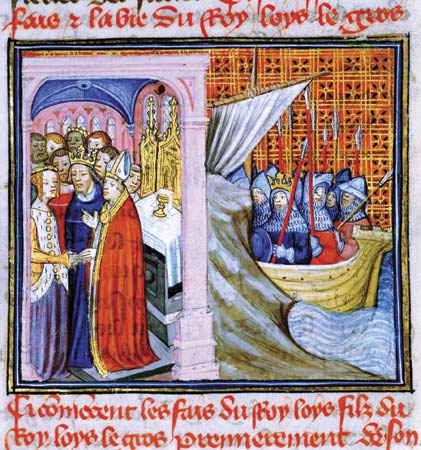

The Central Crusade Trilogy and the Chanson d'Antioche

Textual Analysis

Part 5:

Conclusion

Appendix

Full Bibliography

HISTORIOGRAPHY OF THE MIDDLE AGES

When discussing courtly literature as a far-reaching and wide tradition, it is important to take note of what it means to be 'courtly.' As A.J. Vanderjagt writes, it exists that the idea of "courtly or court literature generally describes colorful, chivalric, and mannerly works which catered to more or less aristocratic tastes and propensities in medieval royal and princely environments."7 He uses this definition specifically in reference to the later middle ages and beginnings of renaissance literature, that is to say the fourteenth century and later, but the notion of courtly literature can be applied to a much broader span of time. There is a different definition for courtly literature as well, and it stems from the reasoning that courtly literature was not simply for the aristocratic class, but by the aristocracy.

William IX of Aquitaine, grandfather to Eleanor of Aquitaine, is considered one of the earliest troubadours. Eleanor herself most likely introduced troubadour poetry to Northern France and England.8 Eleanor's son, Richard, famously the 'Lionheart' who was one of the leaders of the King's Crusade in 1189 CE, also dabbled in verse. Some of the most famous lais and verse poems are from Eleanor's daughter by her first marriage to Louis VII, Marie de Champagne. Marie was "a patroness of poets, notably the celebrated Chrétien de Troyes, creator of the Lancelot-Guinevere romance.9 Heroic poetry has, then, been associated with the Crusades and nobility since its conception. Courtly literature, by extension, is relatively isolated within the field of history and literature, as it was written by those at court solely for those at court. Although Eleanor herself participated in the Second Crusade and Richard effectively led the Third Crusade, the court poets remained at home. Therefore, what we see in the majority of examples of courtly literature is an idealized version of what chivalry should have been on the battlefield, but far removed and closed off from the reality of events.

It cannot be said that the chansons de geste and courtly literature are one and the same, though they share very specific characteristics. Taste in the chanson de geste was waning by the second half of the thirteenth century, making way for more romantic prose from legend, rather than knightly deeds of history. In a sense, chanson de geste was both an isolated form of poetry not typical with 'courtly literature' as well as a product of it.

Simon Gaunt argues against the practice of separating the two forms with such loose terms as 'oral' and 'written' by stating that "written texts were 'voiced' and a written text will often assume an audience of listeners while nonetheless invoking a written text or even specifically signaling the mediating or presence of a book."10 That is to say, an 'oral' poem, such as the chansons de geste, may not have been limited to simple recitation from memory, but that it was also the act of 'reading' as Keith Busby points out.11 This does not detract from the oral quality or origins of the chanson de geste, but it does provide an answer for the need of vernacular verse in order to make it more accessible, as well as giving it a more structured form. In this way, the chanson de geste is brought closer to its courtly counterpart. "This does not mean that the oral mode immediately became extinct when the firsit illuminated manuscript appeared. Nor- and this is more important- does it mean that the illuminated manuscript was used only for individual reading."12 Texts were copied over and over for many years after their composition, and the creation of new modes of literature did not make previous ones obsolete in such a short time.

The Chanson d'Antioche, which is the focus of this paper, would have been sung or read aloud in a vernacular understood by laymen. It not only inflated the glory of the crusaders but reminded the laymen why the crusades were so important. As with the Roland preceding it, the Antioche's author or composer was obviously well-schooled in classical and religious learning.13 One chronicler of the First Crusade wrote, as if with this knowledge in mind, "A plea to all those who will read this history, or hear it read to them and think about it as they listen."14

At times we see events highly changed in order to properly reflect the need for epic device. In regards to the French chanson de geste, or 'song of deeds,' a tradition which spanned roughly the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, is as Michael Newth states, "the literary culmination of a long and largely unknown oral tradition of epic chant inspired originally by the legendary history of Emperor Charlemagne and by his role as Defender of Christianity."15 He goes on to say these songs were often enjoyed and well-received by the aristocracy and the Church. The earliest of these chansons is the Chanson de Roland.

The Roland dates from the early twelfth century, when "Both of these ruling forces [the Church and the Barons] were united by the First Crusade...the original chansons de geste were composed by the trouvères and intended for public performance by the jongleurs."16 As a result of being performed over wide areas and for changing tastes, the narratives themselves were often changed and flowing, indicative of the oral aspect of chanson de geste. The Antioche strongly reflects this oral tradition as well. In the style of what would definitely be considered a later form of chanson de geste, the Antioche reflects local heroes in the style of Charlemagne, but does not include episodes of romance and courtly chivalry in the manner we might expect. Therefore, its audience was either not entirely aristocratic, or for some reason the particular court was not interested in the courtly romance theme which was growing more popular.17 The Chanson de Roland is very much defined in some ways by its ornamental language: "Dancing, singing, and storytelling...are part of the folklore of all nations."18 Demonology and magic, as well as taking care to name the weapons and horses of the knights are common throughout the Roland. This aspect of literary tradition is mostly missing from the Antioche.

Texts which were based on eyewitness accounts were important to the development of medieval literature. Conor Kostick wrote in his essay, "For [the chroniclers], it seemed that the eyewitness works failed to draw out the appropriate theological lessons."19 The idea of an eyewitness is particularly interesting, especially when concerning the validity of first-hand accounts and is the bane of most narrative or poetical histories. Also, texts which would have been written by an eyewitness or with the help of one, were less likely to be questioned. Chronicling, however, was not always done by an eyewitness but with second-hand knowledge.

"Clerical activity in the eleventh century was not restricted to chronicling events that impressed contemporaries...there arose in the Middle Ages a group of writers- known today as hagiographers- who developed a vast corpus of fiction loosely termed saints' lives...Certain hagiographic themes and narrative techniques appear in the Song of Roland. Saints' lives were read, but others- in the vernacular and in metrical form- were sung by jongleurs, constituting an important contact with the chansons de geste."20 Also, as Geert Claassens writes, "The miracle of the numerous saints' lives were assumed to be true: skepsis on that part would not only disqualify the story, but also take the ground from under the cherished concept of 'sanctity.'"21

- Better World Books : Life in a Medieval Castle

"The authors allow medieval man and woman to speak for themselves through selections from past journals, songs, even account books."--"Time" - Alibris : Orality and Literacy in the Middle Ages

In this volume, scholars from Britain, Germany and North America follow Green's insistence on the conjunction of medieval orality and literacy, and show how this approach can open up new areas for investigation. - Better World Books : Performing Medieval Narrative

Broad and wide-ranging survey of and investigation into the important question of whether medieval narrative was designed for performance. - Better World Books : The Song of Roland, An Analytical Edition Vol. 1

Published to observe the twelfth centenary of the Battle of Roncevaux, the event that inspired the Chanson de Roland, this edition provides the first systematic analysis of the entire poem. - Better World Books : Medieval Narrative Sources, A Gateway into the Medieval Mind

More than ten years ago, some mediaevalists of the K.U.Leuven and the University of Ghent joined together to create a repertory of medieval narrative sources focusing on the southern Low Countries.

RELIGIOUS AND ECCLESIASTICAL GOALS OF THE FIRST CRUSADE

In 1091 CE, a letter was supposedly written from the court of Alexius I Comnenus to the Count Robert of Flanders describing a Christian empire besieged by Turks. The letter's authenticity has been much debated and has taken on many forms, but it generally stands that an original is not unlikely nor impossible.22 This letter, as Jean Flori states, "then evoked the tragedy that would have been the loss of Constantinople: a city effectively brimming with relics that must stay in the hands of Christians...better that they fall into the hands of Latins than the Turks."23

Jean Flori asks of the Crusade's destination, "But to where? Until the recovery of territories recently lost by Alexius? Until Antioch, taken by the Turks ten years earlier? Until Jerusalem, in the hands of Muslims for four and a half centuries?"24 To win back ancient Christendom from the hands of a spiritual and religious enemy would have been a scheme of such grandeur, anyone participating would have been immortalized in the history and legends of their homeland. They would have become a frightening reminder to their enemies of the power of God's army.

Jerusalem was considered the center of the earth, more beautiful and plentiful than any place existing outside of Heaven. It was chosen by Christ, and therefore it was chosen by the Crusade. The Crusade would have required unimaginable resources, and they would have needed to leave behind a trail of allied cities or their delivery of Jerusalem would have meant little if they were entirely cut off from the west. Therefore, we have the justification for Jerusalem, but why Antioch? It was not only Jerusalem which was sought for deliverance, but Antioch as well. "It was a part of the Christian inheritance, more akin to Jerusalem than to Nicea,"25 or, for that matter, to any other city or battle undertaken during the Crusade.

Antioch was an important battle, and an important city, for many reasons. Jay Rubenstein writes that it was at Antioch where "the crusade became a full-fledged holy war...sometime during the army's sojourn at Antioch the rules of war completely changed.26 Antioch's importance during the Crusades was more than its strategic placement in the East. It had a very strong theological grip on the priests and warriors of Christ. Antioch was, after all, the place where Christians were given their appellation for the first time and Saint Peter had been according to tradition, its first bishop.27 Knowing Antioch was not only strategically and politically important but also held a very high status as one of the centers of Christendom helps answer why we have a chanson dedicated to its conquest.

With a society enamored by such a city, it is no surprise the Chanson d'Antioche would have been composed, and sung, during later years in order to invoke that powerful sense of loyalty and duty towards the city. It was sung to remind people of its great importance, to stress the justification of taking back the historic lands of Christendom. Suzanne Akbari makes a very interesting point concerning the third poem of the Central Crusade Trilogy, the Chanson de Jérusalem. This statement can also be applied to the Antioche:

The siege and fall of a city are used as a kind of narrative shorthand to encapsulate complex moments of historical change. One might describe the function of poetics in this mode of writing as a 'crystallization' of a temporal shift, making visible what is normally unable to be seen.28

ENDNOTES

7 A.J. Vanderjagt, "Between Court Literature and Civic Rhetoric. Buonaccorso da Montemagno's Controversia de nobilitate," in Courtly Literature: Culture and Context, (paper presented at the 5th Triennial Congress of International Courtly Literature Society, Dalfsen, The Netherlands, 9-16 August, 1986), 561.

8 Joseph and Frances Gies, Life in a Medieval Castle (New York: Harper & Row Publishers, Inc, 1974), 86-87.

9 Gies, Life in a Medieval Castle, 87.

10 Simon Gaunt, "Fictions of Orality in Troubadour Poetry," in Orality and Literacy in the Middle Ages: Essays on a Conjunction and its Consequences in Honour of D.H. Green, ed. Mark Chinca and Christopher Young (Turnhout: Brepols Publishers n.v., 2005), 121-24.

11 Keith Busby, "Mise en texte as indicator of oral performance in Old French verse narrative," in Performing Medieval Narrative, ed. Evelyn Birge Vitz et al. (Rochester: Boydell & Brewer Inc, 2005), 61.

12 Busby, "Mise en texte," 61.

13 Gerard Brault, The Song of Roland: An Analytical Edition vol 1: Introduction and Commentary (University Park: The Pennsylvania University Press, 1978), 25.

14 Robert the Monk, Historia Iherosolimitana, trans. Carol Sweetenham (Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2005), 75.

15 Michael Newth, introduction to the Chanson d'Aspremont (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc, 1989), xi.

16 Newth, introduction, xi.

17 Newth, introduction, xi.

18 Brault, The Song of Roland vol 1, 21.

19 Conor Kostick, "Courage and Cowardice on the First Crusade 1096-1099," War in History 20 (2013): 35, accessed February 21, 2014, doi: 10.1177/0968344512454517.

20 Brault, The Song of Roland vol 1, 19-20.

21 Geert H.M. Claassens, "The 'Schale of Boendale' : On Dealing with Fact and Fiction in Vernacular Mediaeval Literature," in Medieval Narrative Sources: A Gateway into the Medieval Mind, ed. Werner Verbeke et al. (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2005), 237.

22 Sweetenham, Historia Iherosolimitana, 215-216.

23 Jean Flori, Prêcher la croisade XIe-XIIIe siècle: communication et propagande (Perrin, 2012), 53. "Ce document...évoque ensuite le drame que serait la perte de Constantinople: la ville regorge en effet de reliques qui doivent rester entre les mains des chrétiens...il vaudrait mieux qu'elles tombent aux mains des Latins que des Turks."

24 Flori, Prêcher la croisade, 91. "Mais jusqu'où? Jusqu'à la reconquête des terres récemment perdues par Alexius? Jusqu'à Antioche, prise par les Turks dix ans plus tôt? Jusqu'à Jérusalem, aux mains des musulmans depuis quatre siècles et demi?"

25 Rubenstein, Armies of Heaven, chapter 9.

26 Rubenstein, Armies of Heaven, chapter 9.

27 Flori, Prêcher la croisade, 10. Also see Acts 11:26.

28 Akbari, "Erasing the Body," 146-47.

Hubs related to this project

- Part 1: Chansons de geste and the Chronicles of the First Crusade, Introduction

Paper written for HIST 4499 - Crusades and Crusaders. Department of History & Philosophy, Kennesaw State University. 7 May 2014. The full paper is presented here in a series of hubs. - Part 3: Chansons de geste and the Chronicles of the First Crusade: Chronicles and Source Analysis

Paper written for HIST 4499 - Crusades and Crusaders. Department of History & Philosophy, Kennesaw State University. 7 May 2014. The full paper is presented here in a series of hubs.