Comic Books in the Classroom

In recent years, comic books have seen a surge in popularity in mainstream culture, in part because of the flood of comic book movies coming to theatres. These comic book movies are not only from the superhero genre, such as the X-Men, Spider-Man, and Batman series, but also include films such as Road to Perdition, American Splendor, and A History of Violence.

People are beginning to recognize graphic novels as a literary medium not just for children, but for all ages. In fact, in parts of Europe and Asia, comic books and manga are already as widely accepted as traditional literature. Manga has a wide influence in Japan, enough that 40 percent of material published there is manga; the wide variety in subject matter means that everyone reads them, children and adults alike (Napier 20).

Schools and libraries in America also recognize the value of using graphic novels in the classroom, treating them as literature. Many teachers have weighed in on the effectiveness and benefits of using graphic novels in school. Graphic novels provide more than just entertainment; because of their literary merit, they deserve the attention they are receiving both in classrooms and by general readers.

What's in a name?

There has been some debate over the term “graphic novel.” Some people, including myself, use it as a synonym for “comic book,” particularly those bound in hardcover or paperback form, not stapled. Usually such a book form contains a collection of issues that cover one story. The term is also used to mean “a comic-book narrative that is equivalent in form and dimensions to the prose novel,” or a form “that is more than a comic book in the scope of its ambition” (Campbell 13).

Anne Behler explains that while comic books have roots in serial comic strips, "during the 1970s and ‘80s, comics began to take on a more literary tone; many publishers moved away from the serial publication of short comic books to focus on more complex book-length titles, and as a result, comic readership expanded from children to young adults and adults, who found their preferred format maturing along with them" (17).

Thus, the idea of graphic novels being more complex and literary is linked to their having readers of all ages. While some people do not use the term at all, I use “graphic novel” interchangeably with “comic book.”

Genres: Caped Heroes and More

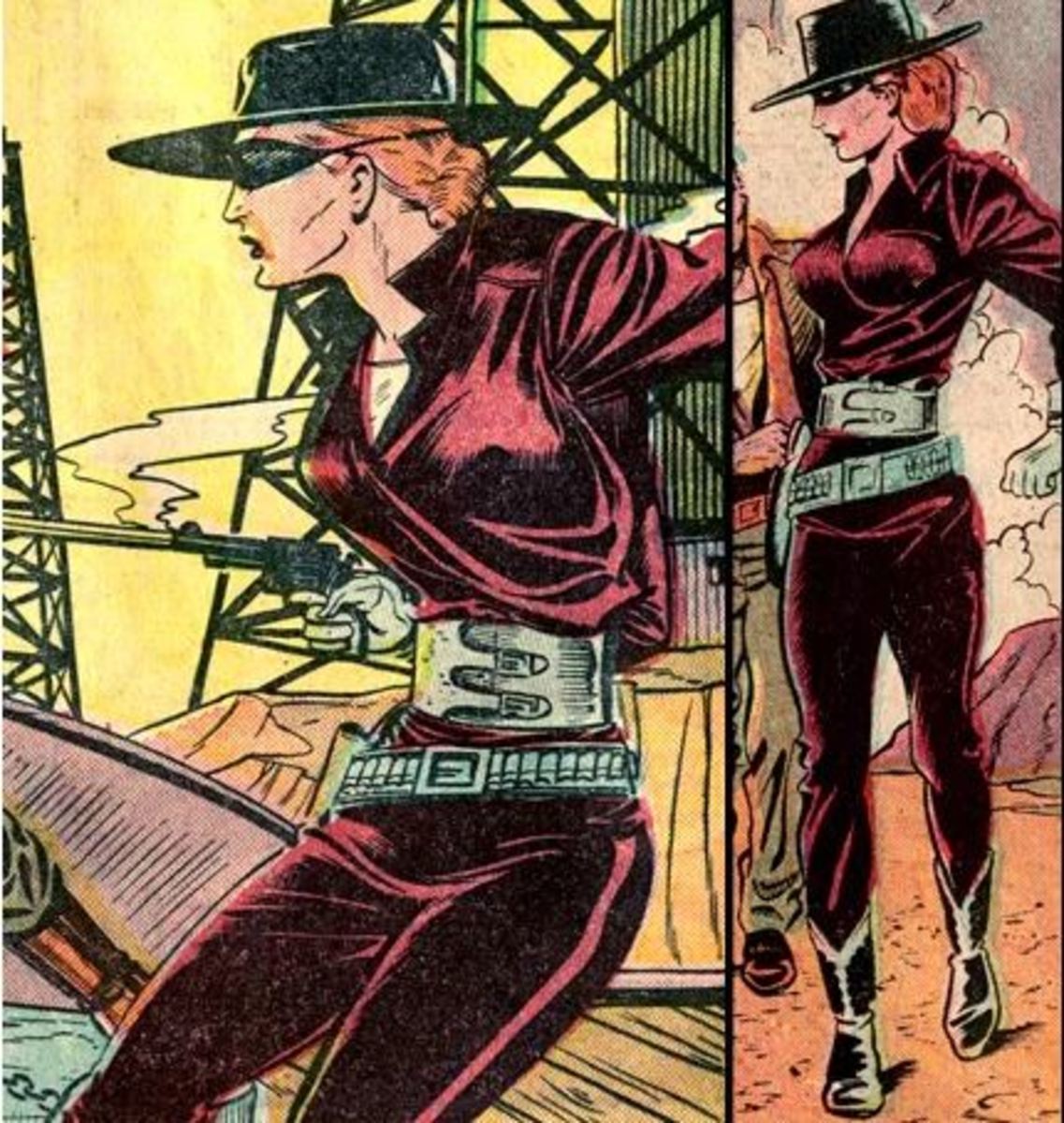

When it comes to comic books, many people do not realize that they cover a wide variety of genres and subjects, and not just superheroes. Graphic novels can be fiction or nonfiction, fantasy or reality. They include adventure, horror, mystery, noir, romance, and drama—effectively every genre that novels follow.

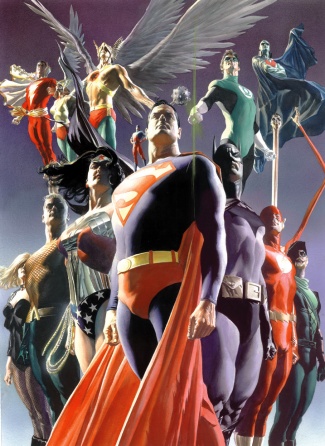

Of course, superhero comics are a form familiar to most people. Besides being very popular and entertaining, the best superhero comics vividly address some crucial questions human beings ask: questions regarding ethics, personal and social responsibility, justice, crime and punishment, the mind and human emotions, personal identity, the soul, the notion of destiny, the meaning of our lives, how we think about science and nature, the role of faith in the rough and tumble of the world, the importance of friendship, what love really means, the nature of a family, the classic virtues like courage, and many other important issues. (Morris xi)

Why the Superhero Craze?

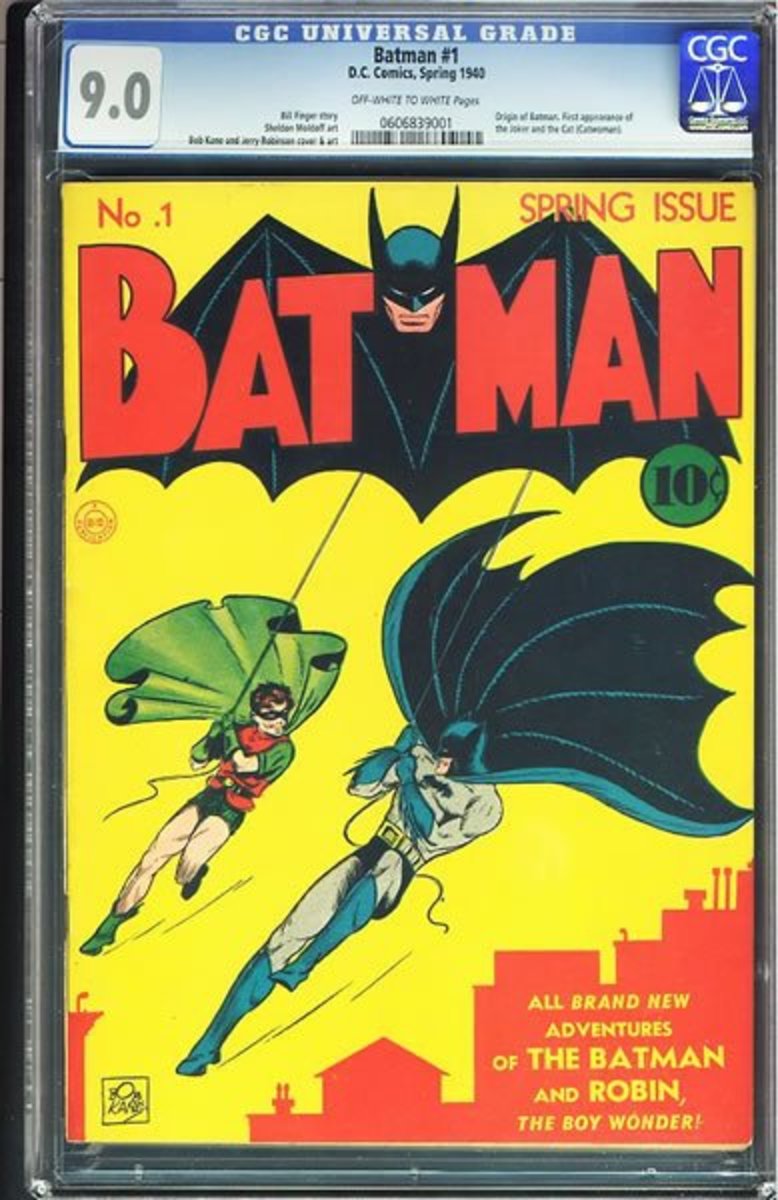

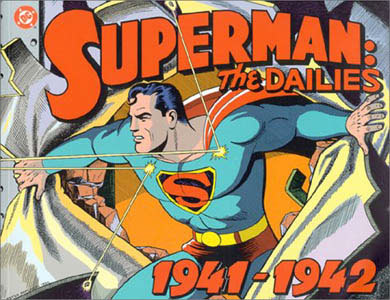

The need for superheroes has not diminished since the first appearances of Superman and Batman in the 1930s; on the contrary, they are prevalent in several areas of popular culture, from music and clothing to recent television shows like Heroes. Superman appears both in the theme song of Scrubs and in Jerry and George’s conversations on Seinfeld (Morris x).

Additionally, Hollywood has cashed in on the comic book craze, creating popular movie franchises, which leads to even more merchandise in stores. Even men and women “who as children never tucked superhero comics into their schoolbooks to rescue them from boredom in class now watch films about Batman and Spidey without shame” (Perret 72). Businesses clearly recognize the allure of comic book heroes, as people love to escape into a world that is both fantastic and real.

Nonfiction Graphic Novels

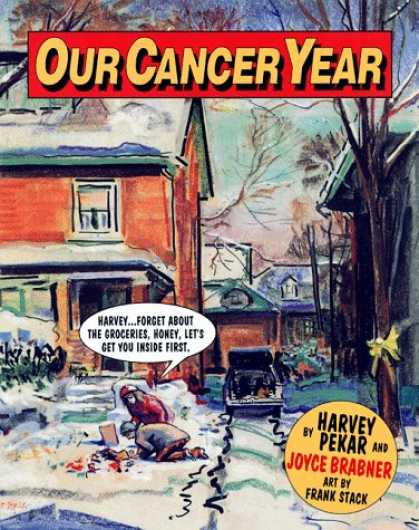

Nonfiction graphic novels cover “such topics as true crime, history, science, biography, and memoir” (Behler 17). An example of memoir is Brian Fies’s Mom’s Cancer, the title both blunt and poignant. Joyce Brabner and Harvey Pekar’s Our Cancer Year also deals with this all-too-real issue, recounting Pekar’s everyday life as he battled cancer. Incidentally, the film American Splendor relates how Harvey Pekar started writing his autobiographical comics, and how his experiences influenced his realistic and honest writing.

Behler also notes that adaptations of well-known stories such as Beowulf into graphic novel form make “accessible to some readers works that would otherwise be off-putting” (17). I will return to the subject of adaptations and how they are used by teachers. Still, graphic novels offer a wide variety of genres and subjects suitable for different audiences.

The Appeal of the Visual

Another curious question about comic books is why they appeal to so many readers. What is it about a series of illustrations with accompanying text that people are drawn to? How is the concept different from children’s picture books? In fact, the merging of words and pictures contributes to the active experience of reading comic books. Unlike traditional literature, graphic novels “are able to quite literally ‘put a human face’ on a given subject” (Versaci 62). In addition to reading a story, readers see the characters and the action through the illustrations. The story occurs through the interplay of text and image. Versaci explains how the marriage of words and pictures requires the active, often subconscious, participation of the reader. Action occurs not only in each frame, but in-between the pictures; in a process called closure, “the reader fills in the details of the empty space between the panels” and is able to empathize with the characters in a unique way (Versaci 63).

Additionally, graphic novels fit today’s culture’s increasing reliance on visual media. People still read, but they also seek entertainment from television, the Internet, video games and magazines. To Stephen Tabachnick, the graphic novel represents an answer to the challenge of such visual media to books. Just as theatre was forced to adapt to the challenge of film, “so traditional literature and the book medium in which it exists have found a way to combine their strengths with that of painting, another threatened medium in the electronic age, and to meet the screen on its largely visual ground while retaining the pleasures and advantages of the book” (25).

Tabachnick notes that “books as a medium are not going away—just as theatre survived films…[t]here is something special—call it privacy and intimacy—between ourselves and a book that we are not ready to give up” (27). At the same time, graphic novels exist as the evolution of the book in an electronic age.

But Are They Literary?

Even if comic books are an answer to the increasing reliance on electronic, visual media, how does that make them literate, as worthy as books? First, graphic novels actually engage the reader and are valuable literacy tools, “exposing readers to twice as many words as the average children’s book” (Behler 17).

Versaci, a literature teacher who uses comics in the classroom, says that although nearly all his students have read comic books before, “many adolescents begin to see comic books as many adults do: subliterate, disposable, and juvenile” (63). However, he argues that this perspective is misinformed, as many people are still “unaware of the maturity and relevance of various comic books” and may associate graphic novels with only superheroes in spandex (63).

Comic Books in the Classroom?!

So what kind of graphic novels are taught in schools, and how do they help students learn about literature? To begin with, graphic novels are great tools to get reluctant readers into books, and adaptations of novels also allow students “to critique the way visual portrayals create meaning” (Behler 17). Graphic novel adaptations range from Beowulf to Shakespeare to Kafka. Tabachnick does not believe that English departments will ever abandon “teaching Melville or Milton in their original, textual versions…although there exist terrific graphic-novel adaptations of Eliot’s Waste Land by Martin Rowson and of Kafka’s ‘Metamorphosis’ by Peter Kuper.” Rather, he thinks that there may be a shift in how often people read graphic novels in comparison to purely textual books (27).

Marion Perret discusses how comic book adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays do more than give students another shortcut in the same vein as Cliffs Notes. Though the aim of these comics is to “introduce readers to the stories and characters entertainingly, comic book versions of Shakespeare’s plays are not just illustrated digests of plots and sketches of character: inescapably, they interpret as well as inform” (73). She notes that there are adaptations written for different ages, with the versions for younger children simplifying the plot or explaining difficult words. For older readers “familiar with the conventions of the medium, interpretation adds awareness of how the artist shapes his material and challenges the reader to become a co-creator who explores ambivalence and ambiguity to find yet more meaning” (73-74).

History Coming to Life

Besides comic book adaptations, other graphic novels are finding their way into class discussions. Lila Christensen recounts how at the insistence of some teenagers at the library, she read Joe Kubert’s Fax from Sarajevo: A Story of Survival, a true story of a family escaping ethnic cleansing in Bosnia. For two years Ervin Rustemagic sent faxes to his friend Kubert describing the bombing and destruction in his town; Kubert arranges photocopies of the faxes “between cartoon sequences and sandwiches the cartoons between prose and photographic pieces—all of which vividly show the reader the reality of war” (Behler 20). Christensen notes how highly informative the graphic novel is as well as powerful, saying that to her surprise, “I learned as much about the Serbian/Muslim/Croatian conflict from a graphic novel as I had from newspapers and the nightly news” (227). She believes that such a work is perfect for a social studies classroom, as are many other graphic novels dealing with true stories of survival.

Perhaps the most popular graphic novel taught in schools is Art Spiegelman’s Maus: A Survivor’s Tale I and II, which tells the story of Spiegelman’s father, a Polish Jew who survived Auschwitz during the Holocaust (Behler 20). Spiegelman’s book is challenging in many ways:

from the complexity of his visual arrangements, to the weight of the subject matter, to his brilliant use (and deconstruction) of an extended animal metaphor by which the nationalities of the people involved are represented by various animals. More so than any other graphic novel, Spiegelman’s work has entered academia and is taught in various types of courses at colleges and universities throughout the country. (Versaci 63)

Maus is a perfect example of how a graphic novel can present history in a powerful way. Teachers should realize that comic books can cover mature subjects that are relevant to students, subjects that can provoke serious discussions. Christensen believes that because graphic novels are popular with teenagers, “using a few well-chosen ones in the classroom to initiate conversations about racism, social justice, war, and global conflict is an intriguing possibility” (227).

Open Discussions

The use of graphic novels in schools also makes students determine what makes a work literary. They may come to realize that literature takes many forms, even comics. Students and teachers alike can discuss how something becomes considered literature and why. Versaci observes that students are often more forthcoming in giving critical evaluations of comic books than in discussing traditional works they may feel are beyond their level of thought. Students are rarely asked to defend or question a traditional novel’s literary value, and doing so for a graphic novel requires them to form an argument and come up with their own definitions of literature (66).

'Cause We Are Living in a Comic Book World

“We are living in a comic-book world,” says Tabachnick, “a world that seems to partake of the elastic landscape of a comic book, so ready to explode from mundane realism into a fantastic shape in a second.” He and other teachers have been teaching Watchmen, a comic that involves a catastrophic attack on New York City, before and since September 11 (27). Indeed, with the fantastic and unexpected events of today’s world, comic books are particularly adept at capturing the reality of people’s experiences. Readers should also examine graphic novels for their literary merits, for their ability to present important people, events, and ideas and to challenge readers to consider things they never thought of before.

Works Cited

Behler, Anne. “Getting Started With Graphic Novels.” Reference & User Services Quarterly 46 (2006): 16-21. Academic Search Premiere. EBSCO. Sturgis Library Electronic Resources.18 Apr. 2007 <http://proxy.kennesaw.edu>.

Campbell, Eddie. “What Is a Graphic Novel?” World Literature Today 81 (2007): 13. Academic Search Premiere. EBSCO. Sturgis Library Electronic Resources.18 Apr. 2007 <http://proxy.kennesaw.edu>.

Christensen, Lila L. “Graphic Global Conflict: Graphic Novels in the High School Social Studies Classroom.” Social Studies 97 (2006): 227-230. Academic Search Premiere. EBSCO. Sturgis Library Electronic Resources. 18 Apr. 2007 <http://proxy.kennesaw.edu>.

Morris, Tom, and Matt Morris. Introduction. "Men in Bright Tights and Wild Fights, Often At GreatHeights, and, of Course, Some Amazing Women, Too!" Superheroes and Philosophy. Chicago: Carus Company, 2005. ix-xiii.

Napier, Susan J. Anime from Akira to Howl’s Moving Castle. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001.

Tabachnick, Stephen E. "A Comic-Book World." World Literature Today 81 (2007): 24-28. Academic Search Premiere. EBSCO. Sturgis Library Electronic Resources.18 Apr. 2007 <http://proxy.kennesaw.edu>.

Versaci, Rocco. “How Comic Books Can Change the Way Our Students See Literature: One Teacher’s Perspective.” English Journal 91 (2001): 61-67. NCTE. Sturgis Library Electronic Resources. 18 Apr. 2007 <http://www.ncte.org>.