The Secret to Developing a Story Worth Reading

The Growing Story

The Death of a Story

Why do we ask the question, “What lies at the heart of this story?” How is it that we so naturally accept that stories have a heart at all? I would suggest that it is because stories, in their own unique way, are living things. When you read a good story you can feel its pulse and sense the air around you shifting as it breathes. Readers revel in stories that are alive.

Of course, it is also quite easy to sense when a story is dead. We, as readers, are masters at sensing the mechanical movements of contrived plot and characters built for convenience. We will not stand for robotic manipulation, even when it is cleverly dressed with the outer clothing of natural human character. No matter how real it might seem, something in our intution rings false, and the story falls flat.

So how do we keep the heart of our stories beating strong when, as writers, we begin with just the smallest fragment of an idea? I nurture the life of my stories by developing them organically:

Organic (adj.)—having the characteristics of an organism : developing in the manner of a living plant or animal

—Merriam-Webster

The Power of a Seed

Plants and animals begin life as a seed—a tiny speck of life that contains the blueprint of its full maturity hidden within, whether it be a daisy or a great oak tree. It grows by building upon itself, by discovering itself through trail and error, and by receiving tender care from a careful, loving hand.

Stories are like seeds—best grown organically.

Caught in the Web

The Structure of a Story in Simple Terms

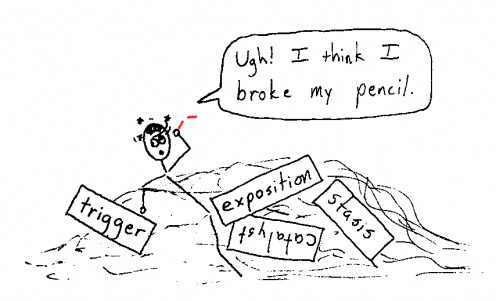

If you Google “structure of a story” you will find many exceptional articles that go to great lengths to dissect the various ways in which stories come together. You will find words like “trigger,” “stasis,” “exposition,” “catalyst,” “protagonist” and a host of other technical terms analyzing how stories work. If you are a writer who loves having more information (my wife exists in a perpetual state of searching for more information), then I highly suggest going and reading them. They can be quite useful.

A Great Article on Structure

I was particularly impressed by this article on “Short Story Structure” by Philip Brewer. It avoids getting too technical while providing a very clear understanding of what distinguishes a short story from larger story structures.

If, however, you are more interested in getting on with your story, then I suggest you simplify. While I fully accept that understanding the subtle complexities of story structure is extremely valuable to any writer, I would also suggest that it is very easy to get stuck in the sticky web of all the grand ideas and forget the basics.

Nancy Atwell, a career middle school writing teacher, in her collection, Lessons the Change Writers, presents the structure of a story in the simplest and most useful terms I have ever seen. She suggests that a character or group of characters that are dealing with a particular problem lies at the heart of all stories.

Examples of Character/Problem Structures

Story Title

| Story Author

| Main Character(s)

| Central Problem

|

|---|---|---|---|

Cinderella

| Traditional

| Cinderella

| Dealing with a feeling of loss and abandonment

|

Crime and Punishment

| Fyodor Dostoyevsky

| Raskalnikov

| Dealing with the consequences of a brutal crime committed for the betterment of mankind

|

Harry Potter

| J. K. Rowling

| Harry Potter

| He lived when he was supposed to have died and is now the key to the downfall of an overpowering evil.

|

The Shining

| Stephen King

| Jack & Danny Torrence

| Jack and his family become isolated with a hotel who's powerful psychic spirit wants to claim Danny for its own.

|

E. T.

| Melissa Mathison (Stephen Speilberg, DIrector)

| Elliot & E.T.

| An alien, discovered by a young boy, is left behind when his ship returns home.

|

That’s it. Looking at any story this way gets straight to the heart of the matter regardless of how simple or complex it might be.

Here’s the important practical outcome of this reality: great stories are not written by developing some complex and elaborate plot map. They are written by staying true the heart of the story.

Growing Your Story Ideas Organically

Compare the following two statements:

- The great advantage of organic food is that everything is natural; plants are allowed to grow according to the inherent laws of how our world functions without permitting artificial or contrived influences to interfere.

- The great advantage of organic stories is that everything is natural; ideas are allowed to grow according to the inherent laws of how our world functions without permitting artificial or contrived influences to interfere.

In both cases, the taste is richer and more deeply authentic.

So how is this achieved? Here is the basic idea, stated in the words of one of the best selling authors of our time, Stephen King, in his memoir, On Writing:

The Author Archaeologist

"...stories are found things, like fossils in the ground...”Stories are relics, part of an undiscovered preexisting world. The writer's job is to use the tools in his or her toolbox to get as much of each one out of the ground intact as possible. Sometimes the fossil you uncover is small; a seashell. Sometimes it's enormous, a Tyrannosaurus Rex with all those gigantic ribs and grinning teeth. Either way, short story or thousand-page whopper of a novel, the techniques of excavation remain basically the same."

Sadly, however much you might want one, I cannot give you a step-by-step process for successfully uncovering the stupendous find that is your story. Every dig is different and every fossil is unique just as every writer’s process is different and every story is unique. I can, however, provide some general guidelines and warnings.

What's Your Writing Style?

How do you approach writing stories?

Story seeds come in many varieties: a single image, a character concept, a suggestive thematic impression or even just a vision of a particular setting. Writers, the careful gardeners and tenders of these seeds, also come in many varieties: those who grab a pen or a laptop and freewrite, forging their way, moment by moment, through the wilderness of the white page, those who carefully plan every maneuver, creating a complex map of interwoven themes, and everyone in between. Great writers and great stories have come out of all of these.

One guiding light, however, remains true among them all; no matter where you begin or how you move forward, the rule to follow when you are actually composing your story is this: watch your characters closely, see how they react to what happens to them, and stay true to who they are and who they are becoming. In the end, it is the characters themselves who actually write the story, you just record it.

Thus, the key to writing your story organically is to identify your central characters, learn who they are without trying to control them, and then throw a problem at them and see what they do. Follow them, and they will lead you home.

Creative Writing Tips

1. Let Go

In the wise words of Obi-Wan Kenobi in George Lucas’s Star Wars: “Let go, Luke. Let go. Trust your feelings.” When trying to write a story organically, you need to expect that your characters are going to surprise you, often spoiling your original plans. They will take the story places you never could have anticipated. Use your feelings and trust them—they usually discover things far more interesting than what you would have come up with anyway.

Example: In crafting the novel I wrote for the thesis of my master’s degree in creative writing, “The Lost Histories of Thoreston Hall”, one character in particular consistently had her own ways of doing things. Early on Mrs. Rutherford kept looking at on object concealed in her hands, but it took her a long time to reveal to me what it was. Near the close of the novel, long after I had developed well-laid plans for her to make the same decision as everyone else in the book, she decided to go her own way instead. Though it required some rewriting, I had to allow it because, otherwise, she would have been false and the story would have failed.

"On Writing" by Stephen King

If you are really ready to invest some time in learning how to write a story well, I highly suggest Stephen King’s book, On Writing. Whether you are a particular fan of his style of work or not (I am not especially so), his plain way of speaking combined with his absolute mastery of the writing craft make this essential reading for any serious story writer. His ideas are simple, direct and very easy to understand, not to mention the laughs you’ll get along the way. Get it. Read it. You’ll be glad you did.

For the Beginning Writer

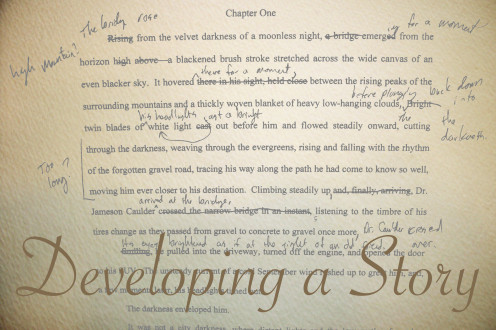

2. Discover the Heart of Your Story, Don’t Force It

In my experience as both a writer and a writing teacher, at least half the time a writer takes this approach to crafting a story, what’s really going on within the story—that is, the deeper problem that is really at the heart of the piece—only emerges after a fair amount of writing is already done. Writers begin with a group of characters facing a problem, and eventually find that problem was only a surface symptom of something deeper, leading to great opportunities for focused revision.

Example: In my thesis novel, “The Lost Histories of Thoreston Hall”, I thought the problem was centered around resolving the issues of all the ghosts that Dr. Caulder discovers haunting the crumbled ruin of Thoreston Hall. While these all played a part, the story turned out to be about Dr. Caulder himself and the deeper personal isolation he experiences as a result of his unique psychic abilities. I did not realize this until the book was nearly complete, requiring a subsequent re-tuning of the entire piece. It was a lot of work, but the story developed a purpose, focus and cohesiveness it preiously lacked.

3. Look Around

One of the natural consequences of this kind of writing is that, once the story starts to go its own way, you may sometimes get stuck in a corner without a clear sense of where to go. My mentor and thesis advisor, the published author Elizabeth Winthrop, gave me great advice: “When you get stuck, look around the room.” That is, go to the place where you are stuck in your imagination and see what’s there. Often there will be an object or a detail you had not noticed before that contains some hidden idea that will breathe life back into your writing.

Example: In my short online ghost story, I got stuck in a place where the main character and the ghost were sitting together talking. I felt the need to reveal a piece of the ghost’s past, but neither of the characters were cooperating. I stopped, looked around the room, and discovered that the ghost was playing with a silver locket hidden beneath the collar of her blouse. This object became the focal point of the history I needed to move forward and created dynamics within the story I had not even considered before.

There is nothing like discovering your own story. It is my sincere hope that something here will help you to experience it.

Happy writing!

wayseeker